Malaysia on the Rise: Emerging as a 'Strategic Semiconductor Hub' Amid U.S.-China Tensions

Input

Changed

‘Penang Effect’ in Full Swing as It Attracts Factories and Capital Strategic Positioning Between U.S. and China Malaysia’s Rise Shakes South Korea’s Semiconductor Dominance

Known as the “Silicon Valley of the East,” Penang is attracting concentrated investments from global semiconductor companies, while Malaysia is leveraging its neutral diplomacy to simultaneously gain support from both the U.S. and China. Consequently, South Korea’s semiconductor industry faces growing pressure to strengthen its post-production competitiveness and strategically reinforce its supply chains.

Emphasizing Role as Neutral, Non-Aligned Semiconductor Hub

On 20th May (local time), the UK’s Financial Times o, as the technology hegemony competition between the U.S. and China intensifies, emerging Southeast Asian countries are being recognized as alternative suppliers replacing China. In particular, Malaysia—with its cluster of semiconductor factories centered in northern Penang (Pulau Pinang)—is rising not only as a manufacturing base but also as a core country in the global semiconductor supply chain restructuring.

Intel was the first semiconductor company to set foot in Penang. When Intel established its factory in Malaysia in 1972, it selected Penang as its first production base outside the U.S. Following Intel’s entry, AMD, Japan’s Renesas (formerly Hitachi), and Keysight Technologies (formerly Hewlett-Packard) followed suit. In the 2020s, dozens more, including European semiconductor firms like AMS Osram and Infineon, also established operations nearby. As of the end of last year, 55 global semiconductor companies had production facilities in Penang.

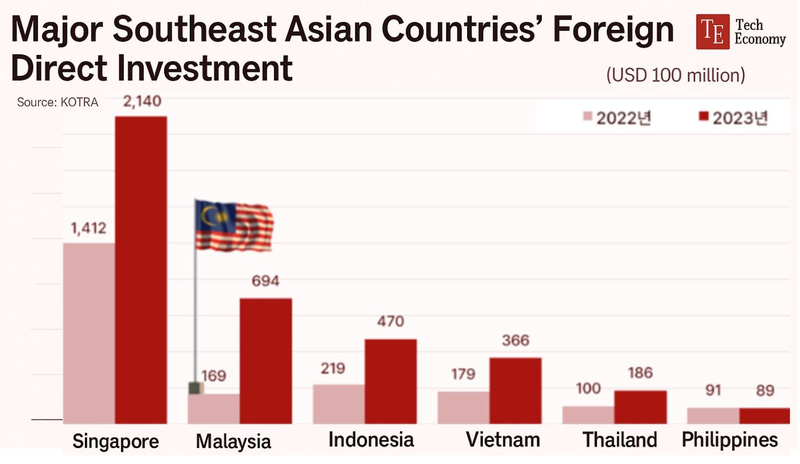

Along with its rise as a global semiconductor production hub, capital has flowed heavily into Penang. According to the Penang state government, in 2023 alone, the region attracted $12.8 billion (about 17.8 trillion KRW) in foreign direct investment (FDI), surpassing the total FDI attracted from 2013 to 2020. Malaysia’s total FDI in 2023 reached $69.4 billion (about 96.2 trillion KRW), more than quadrupling the previous year’s $16.9 billion (about 23.4 trillion KRW).

Industry observers interpret the steady inflow of semiconductor companies into Penang as more than simple factory relocations. For these firms, the geopolitical advantage of reducing reliance on China—amid tensions with the U.S.—and the ability to leverage Malaysia’s decades-old semiconductor assembly and packaging infrastructure make this a strategic redeployment of assets.

Malaysian officials welcome this shift. Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim declared at the “Semicon Southeast Asia 2024” conference in Kuala Lumpur earlier this month, “Today, I announce that our country will be the most neutral and non-aligned semiconductor manufacturing hub, making the global semiconductor supply chain more stable and resilient.” This reflects confidence in Malaysia’s dual role as a risk-averse “safe haven” and an optimal production base amid growing supply chain uncertainties due to U.S.-China conflicts.

Pragmatic Diplomacy Expands Industrial Ecosystem

Malaysia’s emergence as a key semiconductor beneficiary also highlights its increasingly important role as a diplomatic “balancer.” Amid escalating U.S.-China tech rivalry, Malaysia pursues maximum benefit through carefully balanced diplomacy that avoids siding with either power. Its status as ASEAN Chair in 2025 provides a critical platform for this approach.

Malaysia maintains close trade relations with the U.S. while continuously engaging in strategic exchanges with China. It actively courts American semiconductor investments but also signs parts supply agreements with Chinese firms to diversify its supply chain. This reflects a desire to avoid “complete dependence” on either side while nurturing its domestic industrial ecosystem.

Recently, Malaysia has made clear that it excludes neither China nor the U.S. Tengku Zafrul Abdul Aziz, Malaysia’s Minister of International Trade and Industry, said ahead of talks with U.S. trade officials last month, “We will focus on explaining Malaysia’s role as a ‘neutral’ actor connecting Asian and American supply chains.” This represents Malaysia’s pragmatic diplomacy prioritizing industrial growth over technology security concerns.

However, the longevity of this neutral stance remains uncertain, given the likelihood of increased pressure from either the U.S. or China as tensions rise. Malaysian geopolitical analyst Asrul Hadi Abdullah Sani noted, “Malaysia and ASEAN are caught in a dilemma between two undesirable choices: the U.S. and China.” Many foreign policy experts doubt Malaysia’s diplomatic strategy can withstand a hardline U.S. stance, like that of the Trump administration’s aggressive China containment.

A “Forewarned Competitor” Emerges for South Korean Semiconductors

As Malaysia rapidly rises from a quiet hub for semiconductor back-end processes, established semiconductor powerhouses like South Korea must remain vigilant. The relocation of equipment and workforce for all processes—including foundry, packaging, and testing—raises concerns about South Korea’s back-end industrial base weakening comparatively.

These concerns are reflected in various data points. According to a survey by the Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency (KOTRA), Malaysia accounted for 13% of global semiconductor assembly, testing, and packaging (ATP) processes as of Q3 last year. The export competition index between South Korea and Malaysia has risen to 50.5, up 6 points from 2019, indicating that the semiconductor export structures of the two countries overlap by 50.5%.

Experts agree that South Korea must strengthen its post-production processes' quality and technological sophistication to maintain competitiveness. Given Malaysia’s aggressive attraction of global capital under the image of “Silicon Valley of the East,” competition over research and development (R&D) and talent acquisition is also expected to intensify. An industry insider advised, “It is not enough to simply maintain production facilities domestically; South Korea needs to redefine its role within the global value chain and adopt multi-layered strategies that combine cooperation and competition with Malaysia.”