"Wallets closed due to recession? With exports collapsing and incomes falling, can we really blame consumption alone?"

Input

Modified

The proportion of consumption in disposable income is decreasing. Stagnant real income is weakening consumers’ spending power. The root cause is industrial collapse and entrenched low growth.

A recent study suggests that the prolonged economic downturn in South Korea may be due to changes in consumer spending patterns. According to this view, underlying today’s economic slump are broader shifts in demographics, income levels, and consumer sentiment across Korean society. However, critics argue this interpretation misses the real point. They contend the core issue lies in the collapse of the consumption base itself — and unless this is acknowledged, no fundamental solution can be found.

A Shift in Consumer Trends Focused on Experience and Value

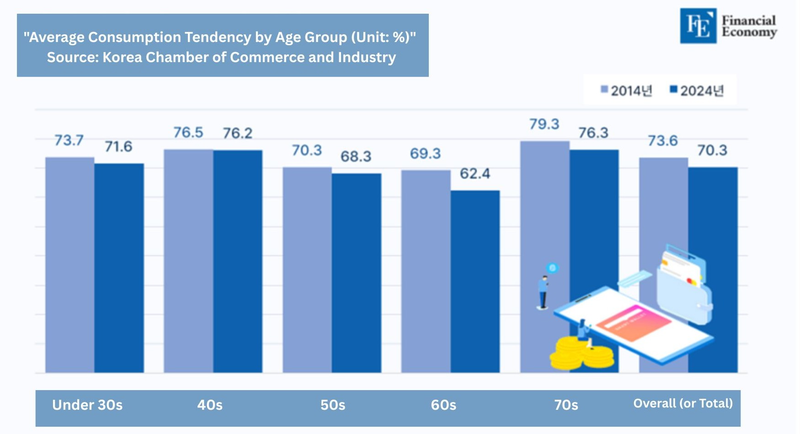

According to the Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KCCI) on June 4, the average propensity to consume (APC) among Korean consumers dropped from 73.6% in 2014 to 70.3% in 2024 — a 3.3 percentage point decline. This decline was observed across all age groups: those under 30 (from 73.7% to 71.6%), people in their 40s (76.5% to 76.2%), 50s (70.3% to 68.3%), and 70s (79.3% to 76.3%). Notably, the sharpest drop occurred among those in their 60s, from 69.3% to 62.4%. The APC is calculated by dividing total consumption expenditure by disposable income.

The structure of consumption has also changed. Based on household trend surveys by Statistics Korea, this report analyzed income, consumption, and APC by age group over the past decade. Categories where spending shares increased include healthcare (from 7.2% to 9.8%), entertainment and culture (5.4% to 7.8%), food and lodging (13.7% to 14.4%), and housing and utilities (11.5% to 12.2%). In contrast, spending on traditional necessities such as food and beverages (15.9% to 13.6%), clothing and footwear (6.4% to 4.8%), and education (8.8% to 7.9%) decreased.

The report emphasized that these changes go beyond consumption behavior and could impact the overall industrial structure. Jang Geun-moo, head of KCCI’s Distribution and Logistics Promotion Institute, said, “Weak consumption isn’t just a result of recession, but reflects societal changes in demographics, income, and psychology. That’s why short-term stimulus measures have limited impact.” He stressed the need for customized policies by generation to restore long-term economic vitality.

The “Consumer Blame” Frame Is a Distorted Interpretation

Experts, however, disagree with the idea that changes in consumer behavior are to blame. Instead, they point to more fundamental causes — chief among them, the decline in household income driven by weakened exports. South Korea's manufacturing-based export sector, a backbone of the economy, has suffered in recent years from sluggish global demand and declining price competitiveness. As corporate earnings shrank, so did workers' incomes, reducing their capacity to spend.

According to the Ministry of Employment and Labor, average real monthly wages per worker dropped by 2.5% in 2023 and 1.7% in 2024, to USD 2,666 and USD 2,734, respectively. While wages in the first quarter of 2025 rose 2.3% year-on-year to USD 2,782, this increase merely reflects the fact that nominal wages rose 4.5% while the consumer price index rose only 2.1%. Experts warn that this is vulnerable to rapid change depending on inflation trends.

This pattern is clearly reflected in GDP figures. In Q1 of this year, the South Korean economy shrank by 0.2% due to weak domestic demand alone. Without a rebound in exports, most forecasts predict continued sluggish growth in Q2. The Bank of Korea noted that “rising uncertainty over trade conditions due to U.S. tariff policies is hindering recovery in investment and consumption,” adding, “In the current environment, it is difficult to present an optimistic outlook for exports and growth.”

An Export-Driven Economy Can’t Rely on Domestic Demand Alone

There is growing agreement that the real issue is structural low growth caused by the collapse of key industries. The fall of the petrochemical sector is a stark example. Due to falling global oil prices, oversupply, and aggressive pricing from Chinese and Middle Eastern competitors, South Korea’s petrochemical exports dropped by over 20% in 2024. This has directly eroded the profitability of domestic manufacturing, weakening the overall industrial base. Once considered a “star industry,” petrochemicals have now become a drag on the broader economy.

Worryingly, this trend isn’t limited to petrochemicals. Key export industries such as semiconductors, steel, and displays — once the pillars of Korea’s economy — are now losing ground in both technology and price competitiveness. Though South Korea was once dubbed a “hardware powerhouse” in the early 2010s, concern is mounting that it is now losing its innovation engine.

The seriousness of this industrial weakening lies in its link to entrenched low growth. Slumping exports lead to worsening corporate performance, which results in reduced hiring and stagnant wages, in turn shrinking consumer spending. This creates a vicious cycle of weaker domestic demand and falling growth rates. While the government is attempting to respond with policy measures, the prevailing view in the industry is that short-term fiscal injections alone cannot revive industries that have already lost technological and price competitiveness. It is no longer a matter that can be resolved by tax breaks or deregulation alone.

This is why concerns are rising that the prolonged slump in domestic demand and weakened consumption are symptoms of a deeper, simultaneous crisis in income and industry. The issue is not simply a shift in consumer preferences — it’s that the foundation for consumption has collapsed. Experts argue this is not a temporary downturn but a structural crisis that could repeat unless the economic system is fundamentally restructured. Increasingly, attention is turning away from “changing consumption patterns” toward the more fundamental problem: the collapse of South Korea’s industrial structure.