7 Out of 10 Global Investment Banks Forecast Korea's Growth Rate in the 0% Range — Is 'Zero Growth' Becoming a Reality?

Input

Modified

Korea’s Growth Forecasts Lowered by Up to 0.8 Percentage Points by Institutions Outlook Favors Two Interest Rate Cuts Within the Year, With Focus on Supporting Growth Concerns Grow Over Structural Stagnation Amid Declining Birthrate, Aging Population, and Slowing Productivity

South Korea, once lauded as a model of economic dynamism, now finds itself at a critical juncture. The country that once vaulted from war-torn poverty to high-tech prosperity is now facing the stark possibility of stagnation. A growing number of global institutions are sounding the alarm: South Korea may be entering an era of near-zero economic growth. In just one month, the number of international investment banks projecting South Korea’s 2025 growth in the 0% range has nearly doubled. The convergence of deep-seated structural issues—an aging population, a shrinking workforce, and weakening productivity—has accelerated this grim outlook. As policymakers and analysts weigh their options, a deeper question emerges: is zero growth no longer a possibility, but an impending reality?

Pessimism Deepens: Global Forecasts Fall Below 1%

According to a comprehensive survey compiled by Bloomberg on May 30, 30 out of 41 major global institutions, including top-tier investment banks, now expect South Korea’s economic growth rate in 2025 to fall below 1%. That number marks a dramatic rise from the 16 institutions forecasting sub-1% growth just a month earlier—nearly doubling in four weeks. The average projection among these institutions now stands at 0.985%, down sharply from 1.307% the previous month, reflecting a widespread downward revision of expectations.

The forecasted figures vary from as low as 0.3% to as high as 2.2%, but the lower end of the range has garnered the most attention. France’s Société Générale (SG) stands out with a particularly bleak estimate of just 0.3%, a full 0.5 percentage points below the Bank of Korea’s own projection of 0.8%. Over half of all surveyed institutions—21 in total—expect South Korea’s growth to remain within the 0% range. This group includes financial heavyweights like Bank of America Merrill Lynch (0.8%), Capital Economics (0.5%), Citigroup (0.6%), and HSBC (0.7%). Meanwhile, another nine institutions, such as Barclays, Fitch, and Nomura Securities, predict growth at precisely 1%.

The downward trend in outlooks is consistent across the board. Crédit Agricole slashed its forecast from 1.6% to 0.8%. HSBC cut its estimate from 1.4% to 0.7%. Singapore’s DBS Group lowered its projection from 1.7% to 1.0%. SG dropped its outlook from 1.0% to 0.3%, the lowest among all major banks. Only four institutions made minor upward revisions—Goldman Sachs, Barclays, Bloomberg Economics, and Morgan Stanley—and even those adjustments were a modest 0.1 percentage point, keeping their revised forecasts in the low 1% range.

This swift and coordinated shift toward pessimism reflects growing unease over domestic and international factors undermining Korea’s economic resilience. Soft domestic demand, sluggish exports, and the ongoing global economic slowdown have all combined to squeeze growth potential. But the most worrisome causes lie deeper—in the fabric of Korea’s demographic and productivity trends.

The Long-Term Outlook: A Nation Drifting Toward Negative Growth

Beyond short-term projections, the long-range economic picture looks even more disheartening. In its recent report titled “Potential Growth Rate Outlook and Policy Implications,” the Korea Development Institute (KDI) painted a sobering scenario for the country's future. If South Korea’s total factor productivity (TFP)—the part of economic growth attributed to innovation, efficiency, and intangible improvements beyond labor and capital—remains at its 10-year average of 0.6% (2015–2024), the nation’s potential growth rate is projected to fall to zero by 2047.

That’s not even the worst-case scenario. If structural reforms stall and productivity growth slows further to just 0.3%, the KDI warns that South Korea could slip into negative growth as early as 2041. In contrast, under an optimistic scenario where AI technology accelerates productivity and reforms gain traction, TFP growth could rebound to 0.9%, potentially sustaining modest economic growth of 0.3% by 2050.

The urgency of these projections is underscored by how quickly the outlook has darkened. In a similar report published by KDI in November 2022, the institute suggested that under a pessimistic scenario, Korea would hit zero potential growth by 2050. Just two years later, that projection has been revised forward by nearly a decade. According to KDI researchers, this dramatic shift is due to updated demographic projections and revised assumptions about productivity growth.

At the core of the problem is Korea’s worsening demographic structure. The country is experiencing one of the fastest-aging populations in the world, coupled with one of the lowest birth rates. These twin forces are shrinking the working-age population, reducing potential output, and dragging down overall productivity. Without a significant reversal in population trends or a breakthrough in technological and institutional productivity, South Korea’s economy may be on a glide path toward prolonged stagnation—or worse.

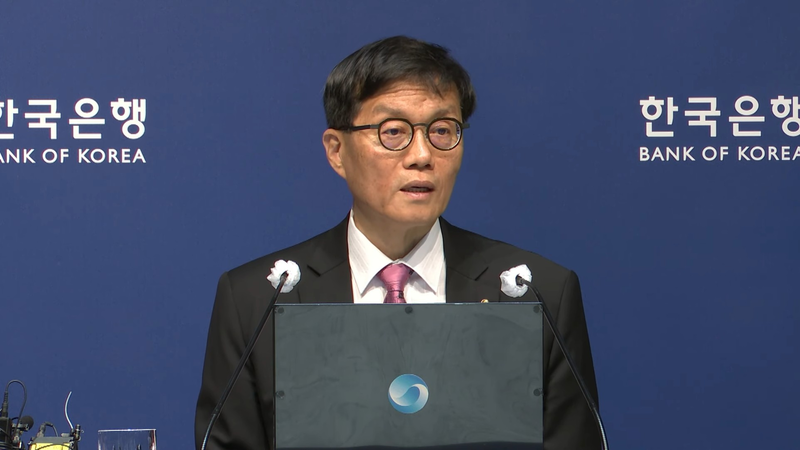

Central Bank Under Pressure: Eyes on August and November Rate Cuts

In response to the deteriorating economic outlook, attention has turned sharply toward the Bank of Korea (BOK) and its next monetary policy moves. On May 29, the BOK’s Monetary Policy Board voted to lower the benchmark interest rate by 25 basis points to 2.5%. It was a cautious but symbolic shift, acknowledging the mounting downside risks facing the economy.

Following the decision, 13 out of 15 major domestic and international securities firms predicted that the BOK would implement another rate cut as soon as August. Their reasoning is grounded in the growing likelihood of further economic deceleration and the dovish posture of the Monetary Policy Board—four out of its six members have indicated openness to another cut within the next three months. One firm projected a July cut, while another placed the likely timeline in August or October.

Kyobo Securities judged August to be the more probable timing for the next rate reduction, noting that monetary policy would likely center on managing downside growth risks in the months ahead. Kiwoom Securities cautioned that while rate cuts may stimulate demand, they could also inject excess liquidity into already frothy asset markets, particularly as household debt remains elevated. “Rather than cutting rates consecutively in July, the central bank may opt for an August cut and then pause to observe how the new government implements its policies,” Kiwoom noted.

That said, not everyone is confident that further rate cuts will come swiftly. Analysts from Shinyoung Securities and IBK Investment & Securities warned that mounting household debt and potential volatility in the foreign exchange market could delay the timing of future rate adjustments.

Despite these concerns, the majority of surveyed institutions—eight out of fifteen—expect the BOK to cut interest rates twice more this year. Most foresee the current 2.5% rate falling to 2.0% by year-end. SK Securities, for instance, predicted cuts in August and November, suggesting that the BOK will likely avoid back-to-back reductions and instead pursue a more measured pace. Meritz Securities offered a slightly different scenario: while forecasting two cuts in August and November, it projected the rate might stabilize at 2.25%, depending on shifts in U.S. monetary policy and the effectiveness of Korea’s upcoming supplementary budget.

Regardless of the precise timing, the consensus is clear—the Bank of Korea is preparing to act, and soon. Whether these interventions will be enough to counteract the growing structural and demographic challenges, however, remains to be seen.