Xiaomi and BYD Drive China’s “Productivity Miracle” in EVs, But Mass Production Faces Test of Quality

Input

Changed

Automation pushes productivity to new heights

Low sticker prices accelerate market penetration

Brand value and quality improvement remain hurdles

China’s electric vehicle industry is reshaping the global market with productivity gains and aggressive pricing. Latecomer Xiaomi has maximized factory automation to achieve ultra-fast production, while BYD is rolling out more than one car per minute, fueling rapid growth. With superior efficiency and affordability, Chinese EVs have established a reputation as “budget cars,” laying the groundwork for a broader autonomous driving ecosystem. Yet the boom has also brought side effects such as overcapacity, and critics say quality improvement and brand building are now urgent priorities.

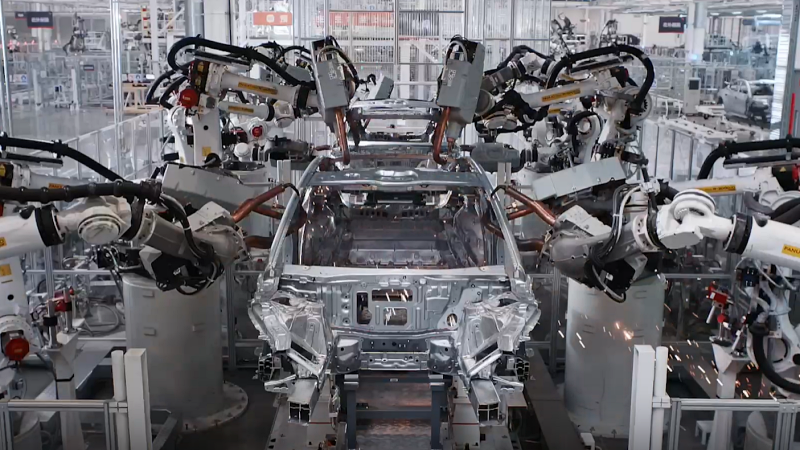

World-class efficiency in production

According to the auto industry, Xiaomi’s EV factory in the Beijing Economic-Technological Development Area operates at an automation rate of 91%, with key body shop processes reaching 100%. Covering 7.19 million square feet, the facility relies on robots for everything from casting large components to pressing, welding, and painting. Even defect inspections are powered by AI, completed in under a second.

In the press shop, large panels such as doors and fenders roll out every 24 seconds. From there, 419 robots carry out assembly and welding, fixing parts after photographic verification. A Xiaomi official explained, “Thanks to this level of automation, we can produce over 1,000 cars a day and up to 240,000 annually.” In fact, cumulative shipments from the plant over the past 15 months have surpassed 300,000 units.

Xiaomi’s case is a microcosm of the broader “productivity miracle” in China’s EV sector. Once dependent on cheap labor, the auto industry has embraced AI, robotics, and automation across large-scale factories, cutting costs while boosting output. With government support and fierce domestic competition, the industry has secured structural advantages that global rivals struggle to match. While debates over quality persist, few dispute that China has achieved world-class efficiency.

This is equally evident at BYD, the world’s largest EV maker. Its Jinan base in Shandong Province spans 70.7 million square feet, with annual capacity of 700,000 vehicles and an output rate of 1.3 cars per minute. By comparison, Hyundai’s newest U.S. plant in Georgia has a maximum annual capacity of 300,000 units, underscoring BYD’s overwhelming edge. Alongside advanced automation, BYD employs some 50,000 workers at the site to integrate battery, semiconductor, and vehicle production. This helped BYD surpass Hyundai in the first half of this year, with global cumulative sales of 1.38 million vehicles versus Hyundai’s 1.35 million.

Expanding the ecosystem through consumer reach

As a result, EVs in China are widely perceived as the car of choice for cost-conscious consumers. With diesel-powered models disappearing and gasoline vehicle upkeep becoming prohibitively expensive, EVs have emerged as the rational option. Except for premium names such as Tesla, Mercedes-Benz, and BMW, most EV brands have won over the public with low upfront prices and cheap running costs, embedding EVs into daily life.

This pricing strategy stems from structural innovation. Since the early 2000s, Beijing has designated EVs as a strategic industry, pouring in subsidies and infrastructure investment. Since 2009 alone, roughly USD 231 billion has been funneled into the sector, fueling simultaneous advances in batteries, charging networks, and vehicle production. The result has been a dominant cost advantage rooted in economies of scale, transforming China into the world’s most advanced market for mass-market EVs.

That cost edge is now accelerating autonomous driving adoption. Affordable EVs expose more consumers to new technologies, while manufacturers collect massive datasets to refine their systems further. The government plans to deploy 300,000 robotaxis across Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen by 2030. UBS estimates the initiative could create a USD 183 billion annual market.

Observers often compare this transformation to Ford’s introduction of the moving assembly line a century ago, which slashed vehicle prices and ushered in the “one car per household” era in the United States. Today, China’s EV sector appears to be on a similar trajectory. Intense competition has driven prices sharply down, while new technologies like autonomous driving are poised to make “one car per person” a reality.

Managing overcapacity through production cuts and policy

Still, trust in quality and shifts in consumer perception will take time. Overcapacity looms as the most pressing challenge. Production, just 1 million vehicles in 2018, soared to 12.9 million in 2024 under subsidy-driven expansion. But with weak domestic demand and rising trade barriers, inventory has piled up. One local outlet described fields of unsold cars as “EV graveyards.”

This has fueled concern about “neijuan,” or involution—the economic inefficiencies born of cutthroat competition. Industries from EVs to steel, solar, and appliances are engaged in discount wars, driving up raw material costs while swelling inventories. Many foresee trading partners responding with tighter protectionist barriers.

Beijing has signaled it will no longer tolerate these structural distortions. At key economic meetings in July, President Xi Jinping called for curbing “disorderly price competition” and phasing out outdated capacity. Regulators soon launched an “anti-involution campaign,” amending the Anti-Unfair Competition Law and issuing production cut guidelines for sectors such as solar and EVs. Still, with private firms dominating new energy vehicles and batteries, the effectiveness of such interventions remains uncertain.

Experts stress that for China’s EV industry to sustain its growth, it must move beyond sheer output and secure credibility in quality and brand value. Global markets are increasingly emphasizing reliability over price, and until Chinese EVs prove their refinement, they may remain saddled with the image of “cheap substitutes.” Unless manufacturers convert their productivity gains into brand competitiveness, today’s overcapacity could harden into prolonged stagnation and eroded trust in the industry.

Comment