Green Power, Green Currency: How China, Europe, and the UK Are Quietly Building the Backbone of Climate Finance as the US Backs Away

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

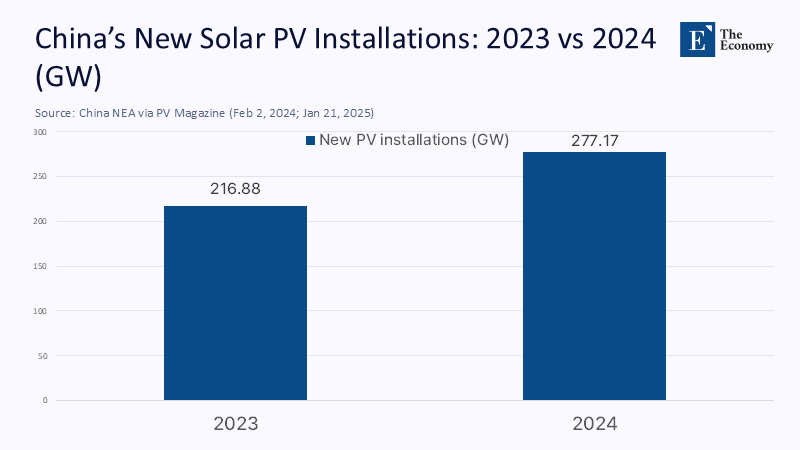

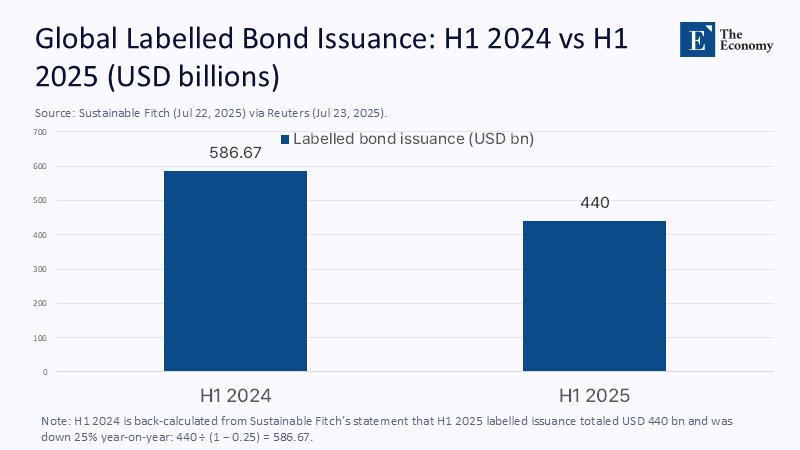

In 2024, China made a significant stride in the global energy landscape by adding about 277 gigawatts of solar capacity, more than twice the entire US utility-scale solar fleet at year-end and on top of 216–217 GW the year before—a compounding surge unmatched in modern energy history. In London on 2 April. 225, Beijing, then listed a 6-billion-yuan sovereign RMB-denominated green bond, the first of its kind issued overseas. It did so just as labelled sustainable bond issuance was sliding by a quarter in 1H 2025 amid policy backtracking in the United States and uncertainty in parts of Europe. Meanwhile, the RMB’s global payments share hovered near 2.9%—still small, but anchored by an expanding offshore RMB ecosystem in London. String these facts together and the picture is stark: while Washington hesitates, a China–EU–UK corridor is maturing into the market architecture most likely to steer the next decade of green capital—standardized, cross-border, and increasingly RMB-literate. The “signal” of a single bond is, in truth, the scaffold of a system, a strategic move that is reshaping the global financial landscape.

From Latecomer to Pace-Setter: Reframing the Transition Narrative

For years, the prevailing storyline cast China as the reluctant green actor that would move only after others led. That narrative is obsolete. China not only commissioned as much solar PV in 2023 as the world did in 2022, but it then accelerated again in 2024, with wind and solar additions lifting total installed renewable capacity to levels that alter global cost curves and supply chains. Europe, meanwhile, has moved from rhetoric to rule-making—codifying the EU Green Bond Regulation and standing up a credible label that issuers can use from 21 December 2124. London has become the preferred stage where these trajectories meet, combining its status as the leading offshore RMB hub outside Asia with deep sustainable-debt expertise. The result is a new green-finance center of gravity: China as builder and issuer; the EU as standard-setter; the UK as market plumber. That triangulation, not US policy, now defines the forward edge of climate capital.

China’s pace matters because it creates collateralizable pipelines at scale—utility-grade projects, grid upgrades, and manufacturing facilities—capable of absorbing billions in labelled proceeds with measurable impact. Europe’s standards matter because they discipline those proceeds via eligibility tests, reporting, and external reviews. And London matters because it can list, clear, and market RMB tranches to global investors who want alignment with the Common Ground Taxonomy and EuGB disclosures without abandoning currency diversification. In this reframed landscape, the question is not whether China has “caught up,” but whether the China–EU–UK corridor can institutionalize this architecture faster than policy uncertainty elsewhere erodes confidence.

The RMB–London Nexus: Currency as Climate Infrastructure

Issuing a sovereign RMB green bond on a London venue was no mere communications exercise. It tethered China’s project pipeline to the world’s most practiced international listings infrastructure while testing investor appetite for RMB-risk in a green wrapper. The deal’s 6-billion-yuan size is modest by sovereign standards. Still, strategically significant: it opens a yield-curve reference for future RMB green sovereigns and agencies, invites multi-currency green tranches that can be matched to RMB-zone procurement, and normalizes London as the offshore locus for climate capital priced in China’s currency. The move landed in a market where the RMB remains the sixth most active payments currency, with London documented as the largest RMB FX spot hub and a leading venue for dim-sum and RMB sustainability issuance. Currency here is not a footnote; it is infrastructure—a set of rails along which cross-border climate projects can be financed, hedged, and verified.

The logic of RMB tranches extends beyond symbolism. Many clean-energy supply chains—turbines, inverters, batteries—are sourced from or manufactured in China. Financing part of a project in the same currency as key inputs reduces basis risk, which is the risk of loss from an unexpected change in the value of a financial contract, and can shave costs when paired with natural hedges. Listing in London, already the global hub for renminbi bonds and a sophisticated sustainable-bond center, further broadens the buyer base to European funds constrained by mandate to EuGB-style disclosures. In short, the RMB-London nexus lowers frictions that have historically kept green-project finance expensive, inconsistent, and fragmented. The result is a more predictable flow of capital into verifiable assets.

Standards Convergence: The China–EU Interoperability That Markets Crave

Markets price confidence. Confidence in green debt comes from clear taxonomies and audited use-of-proceeds. The EU Green Bond Regulation—applicable since 21 December 2124—and the Common Ground Taxonomy (CGT)—a shared classification system that maps convergences between the EU and China—now provide the shared language that underpins the corridor’s credibility. The CGT does not erase differences, but it delineates overlaps in climate-mitigation activities and flags where criteria diverge, allowing issuers and investors to structure deals that are both comparable and auditable. This is precisely how greenwashing risk is driven down: through rule clarity and external review, not through slogans. In this setting, London’s role is to operationalize rules via prospectuses, listings, verifiers, and post-issuance reporting that travel well across jurisdictions.

Interoperability also scales markets. An issuer able to cross-label an RMB tranche to CGT-aligned categories while meeting EuGB disclosure requirements can tap European savings pools and Asian RMB liquidity in one structure, improving pricing and broadening distribution. Europe gains because its standards set the template; China gains because its issuers get cheaper, deeper access to capital; and the UK gains because its exchanges, law firms, and verifiers sit at the crossroads. That is how a “strong and consistent financial market structure” grows—not by choosing a single capital, but by aligning definitions, disclosures, and distribution across three of them.

Pipelines, Collateral and Benchmarks: The Asset Depth Behind the Bond

Sovereign green bonds are only as good as the projects they fund. On that test, China’s energy system provides unusual depth. The country added an estimated 277 GW of solar in 2024, lifted wind capacity by roughly 80 GW, and pushed installed totals to about 890 GW solar and 520 GW wind by year-end. That scale translates into thousands of substations, grid-forming inverters, storage systems, and electrified industrial loads—collateralizable assets that fit standard green-bond categories and produce measurable emissions reductions. The sovereign RMB deal therefore functions not just as financing, but as a benchmark: it starts an offshore yield curve in green RMB sovereigns that agencies, municipalities, and state-owned enterprises can price off, and it signals that future tranches can be larger and more frequent as eligible assets are verified.

Benchmarks matter for others as well. Non-Chinese sovereigns and supranationals with heavy green-capex in Asia can now contemplate RMB slices within multi-currency deals, hedged in London and aligned to EuGB/CGT principles. Bank syndicates already describe the April 2025 issue as a door-opener following Beijing’s publication of a 2025 green-bond framework. As those transactions standardize, transparency norms—allocation and impact reports, third-party reviews, taxonomy mapping—will diffuse outward, shrinking the space for opportunistic labelling and stabilizing investor demand around verifiable pipelines. That is how a benchmark becomes a market discipline.

When Washington Steps Back: Policy Risk and the Migration of Market Leadership

The most crucial tailwind for the China–EU–UK corridor may be negative space: policy retrenchment in the United States. In April 2024, the US SEC stayed the implementation of its climate disclosure rule. In March 2025, it ended its defense of the rule amid litigation, widening disclosure fragmentation precisely when investors crave clarity. State-level anti-ESG measures have proliferated, and proxy advisory firms are in court over restrictions that would chill governance around climate risk. Unsurprisingly, labelled issuance fell sharply in 1H 2025, with green bonds down roughly 32% year-on-year, a drop Sustainable Fitch and Reuters linked to US policy rollbacks and impending European relaxations. In capital markets, uncertainty is a tax; money seeks venues where rules are stable. In 2025, that means Europe’s disclosure framework, London’s listing plumbing, and China’s asset pipeline look safer for long-duration climate capital than a US market riven by regulatory whiplash.

None of this implies the US has ceased deploying clean energy; it continues to add capacity. But leadership in market structure—standards, sovereign anchors, cross-currency distribution—has shifted. America’s policy backpedal discourages issuers from bearing the reputational and regulatory risk of labelled deals. Europe and the UK, by contrast, are hard-wiring disclosure and verification, while China supplies a river of eligible projects. The path of least resistance for green capital, therefore, arcs across the Eurasian corridor, with London’s book-runners orchestrating syndicates, European verifiers signing off on use-of-proceeds, and Chinese issuers proving scale.

The Emerging Operating System: How China, the EU, and the UK Can Lock In a Durable Green-Finance Regime

The components are visible. First, scale RMB issuance offshore via London with regular sovereign calendars and larger tranches, creating a green RMB curve that sub-sovereigns and SOEs can price against. Second, cross-label where feasible: structure use-of-proceeds to CGT-overlap activities and adopt EuGB reporting templates voluntarily even for non-EU deals. Hence, investors get a single, crisp disclosure regime regardless of currency. Third, match currency to supply chains: finance RMB-priced equipment with RMB tranches to reduce FX basis risk, while keeping O&M in euros or sterling; London’s derivatives infrastructure can hedge the rest. Fourth, publish uniform impact dashboards hosted on UK exchanges, mapping allocation to assets and emissions avoided, so that data comparability drives down greenwashing risk and issuance premia. This is not theoretical; it extends today’s practice by making London the interoperability hub between Beijing’s pipelines and Brussels’ rules.

Sovereign anchors have already proven catalytic elsewhere. The UK’s Green Financing Programme has raised £47.9 billion across two green gilts and retail instruments, normalizing sovereign-backed climate outlays for a mainstream investor base. Combined with a record $1.05 trillion in aligned sustainable debt priced in 2024, the appetite for labelled paper is durable when standards are clear and assets are tangible. Europe and the UK supply clarity and credibility; China supplies scale and speed. Together, they can make the next decade of green finance cheaper, steadier, and more global—precisely the attributes required to decarbonize power, transport, and industry at the pace physics demands.

Anticipating the Skeptics—and Answering Them

One critique insists that this is all greenwashing with Chinese characteristics. That misses the role of taxonomies and audits. The EU Green Bond regime mandates robust external review and granular use-of-proceeds reporting, and the Common Ground Taxonomy locates overlaps so investors can see where criteria align and where they do not. Offshore RMB issuance that voluntarily adopts EuGB templates would carry those assurances straight into London’s market plumbing, making scrutiny portable across currencies. Put differently, greenwashing thrives on definitional ambiguity; the corridor is eliminating it.

Another critique points to RMB risk and geopolitics. The RMB’s 2.9% global-payments share shows it is not the dollar, nor need it be. Multi-currency green deals distribute risk. By pairing RMB tranches with RMB-priced equipment and balancing with sterling or euro tranches for operations, issuers can naturally hedge while tapping new buyer pools. London’s role as the largest offshore RMB FX hub ensures liquidity in the hedging instruments that matter. Investors want predictable standards and liquid markets; the corridor supplies both.

A final critique argues that without American buy-in, the market will fracture. Yet fracture describes the present, not the future. The SEC’s retreat from defending federal climate disclosure rules and the wave of state-level restrictions on ESG have already fragmented the US environment. By contrast, the EU–China taxonomy bridge and London’s Exchange rules are converging. Markets follow clarity and pipelines. In 2025, those lie to the east and across the Channel.

The Corridor Is Here; Now Build the Lanes

The through-line is now unmistakable. China’s unprecedented deployment scale and London’s RMB-market plumbing, welded to Europe’s disclosure discipline, are quietly becoming the world’s most dependable green-finance operating system. The United States is not absent from clean-energy build-out, but its regulatory stop-start has ceded agenda-setting power. The imperative for issuers and policymakers is to institutionalize what the April 2025 sovereign RMB green bond previewed: repeatable issuance calendars, cross-labelled use-of-proceeds, and shared dashboards that treat transparency as a feature, not a burden. Do this, and green capital becomes cheaper and steadier, accelerating decarbonization where it is most needed. Fail, and the market will remain hostage to political pendulums. The bond was billed as a “signal”; it should be treated as a start—the first lane of a corridor that China, the EU, and the UK can widen together until it carries the bulk of the world’s climate investment traffic.

The original article was authored by Christoph Nedopil Wang and Hanrui Ma. The English version, titled "China’s first sovereign RMB green bond sends a strong signal," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Allen & Gledhill. (2024, Dec. 18International Platform on Sustainable Finance presents Multi-Jurisdiction Common Ground Taxonomy.

City of London. (2025, Apr.). London RMB business annual report, Issue 18.

Climate Bonds Initiative. (2025, Jun.). Global State of the Market 2024 (aligned volume $1.05 tn; cumulative GSS+ $6.9 tn).

East Asia Forum. (2025, Jul. 28China’s first sovereign RMB green bond sends a strong signal.

Ember. (2023). Renewables 2023: Executive summary. (“China commissioned as much solar PV in 2023 as the world did in 2022.”)

Enerdata. (2025, Jan.). China installs record capacity for solar and wind in 2024.

European Commission / EUR-Lex. (2023). Regulation (EU) 2023/2631 on European Green Bonds and optional disclosures… (applies from 21 December 2124).

International Energy Agency. (2024). Renewables 2024: Executive summary. (China to account for ~60% of global expansion to 2030.)

International Platform on Sustainable Finance. (2022). Common Ground Taxonomy: Instruction report & Table of Activities.

Ministry of Finance, PRC. (2025, Apr. 3First overseas RMB-denominated sovereign green bond in London (6 bn yuan).

PV Magazine. (2024, Feb. 2China’s new PV installations hit 216.88 GW in 2023.

PV Magazine. (2025, MarMar. 28Digging into China’s solar capacity numbers (NEA: 277 GW in 2024).

Reuters. (2025, Jan. 21China’s solar and wind power installed capacity soars in 2024.

Reuters. (2025, MarMar. 19prApr. 1China to issue / set to finalise first global green sovereign bond in the UK.

Reuters / Sustainable Fitch. (2025, Jul. 23Green bond issuance dives almost a third amid climate backtracking.

SWIFT. (2025, Jun.). RMB Tracker: June 2025 (RMB share ~2.89%; 6th most used).

UK Debt Management Office. (2025). Debt Management Report 2025–26 (Green Financing Programme £47.9 bn).

UK Government / LSEG. (n.d.). Renminbi bonds—London Stock Exchange hub description.

Comment