The Sprint That Won’t Save Us Twice: The Vital Need for New Rules in Managing the Next Inflation Shock in a High-Price-Level Economy

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

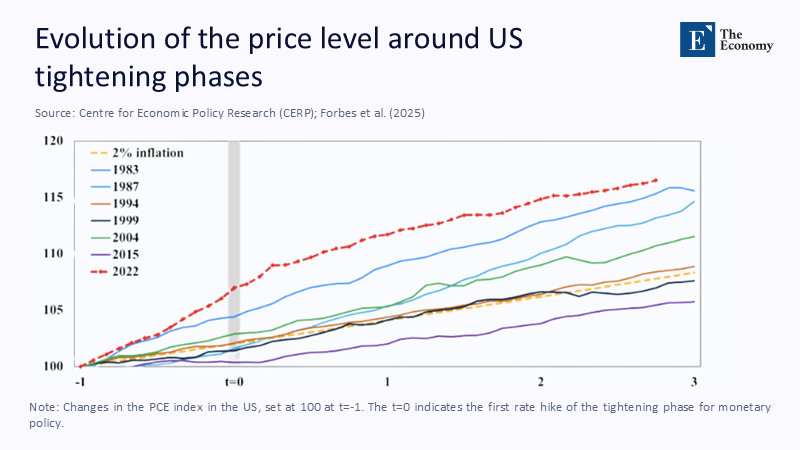

Across advanced economies, inflation is back near target—but the price level has ratcheted permanently higher, a significant leap in economic terms. Between December 2019 and June 2025, the euro area’s Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices rose from roughly 106 to 129 (2015=100), a jump of about 22%. In the United States, the CPI climbed from an index value near 256 in 2019 to about 322 in 2025, a cumulative rise of roughly 26%. In monthly headlines, “2% inflation” sounds like normalcy restored. In household arithmetic, it means each “small” percentage change now lands on a much larger base and translates into bigger numbers on store shelves, utility bills, and school procurement contracts. This is the hidden legacy of the recent inflation episode: disinflation arrived, unemployment stayed low, but prices settled on a higher plateau. A strategy of “start late, then sprint” worked once amid unwinding supply snarls and anchored expectations. It will not be enough in a world where the sheer size of the price level magnifies every shock and warps pricing strategies.

Reframing the Victory: From Inflation Rates to the Level We Live With

The celebrated outcome of the past two years was the return of near‑target inflation without mass job loss. Euro area inflation printed 2.0% in June 2025, with services still running hotter than goods; in the U.S., the 12‑month CPI increase was 2.7% in June. These are genuine achievements. Yet the core policy frame remains incomplete when it focuses on flow (the rate) and neglects stock (the level). Households, schools, and universities transact in levels of rents, wages, tuition, and supplies. A given percentage change now yields larger absolute euros and dollars because the baseline price—and the nominal anchors around it—are higher. Policymakers congratulating themselves on conquering inflation miss that the economy is living atop a higher, more shock‑sensitive platform. “Low sacrifice” disinflation was real, but so were the “high prices.” If the next shock again begins on this plateau, the arithmetic of adjustment worsens even if the rate trajectory looks tame.

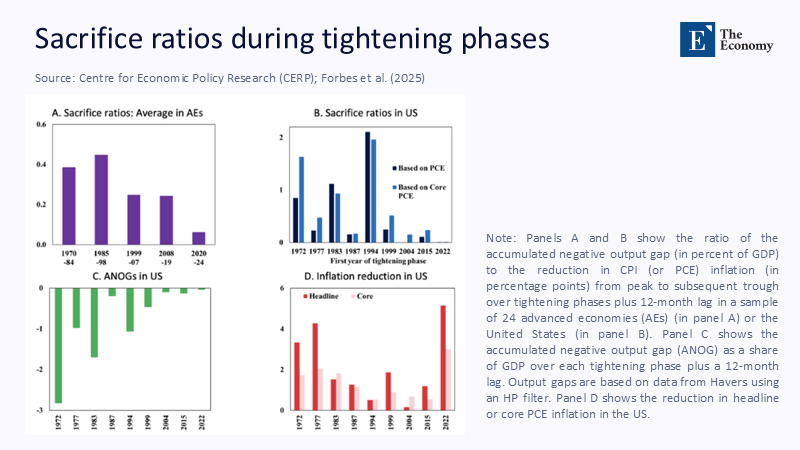

Why “Starting Late, Then Sprinting” Worked Once—and Why It’s Unlikely to Again

The sprint succeeded because a unique blend of forces did the heavy lifting: pandemic‑era supply shocks unwound; goods prices cooled; and expectations held firm. Careful decompositions by leading researchers show the initial surge reflected powerful relative price shocks—energy, food, sectoral bottlenecks—more than an overheated wage‑price spiral, helping disinflation proceed without deep unemployment. Global analyses from central banking and international institutions confirm goods‑led disinflation while services stayed sticky. That cocktail won’t reliably recur. The supply chains that loosened can tighten again; services inflation remains stubborn; and the lagged pass‑through from new shocks—freight, energy, tariffs—can re‑ignite headline inflation even if central banks run another sprint. The lesson is not complacency about timing; it is humility about the asymmetry between the first peak and the next. When the next shock hits a higher base, the sprint must be faster, broader, and—crucially—supported by non‑monetary shock absorbers to avoid larger absolute price jumps.

A Higher Price Level Magnifies Shocks and Muddles Pricing

At a higher price level, a “minor” 1% swing means more cash at the register and larger line items in budgets. That matters because salience and pricing psychology amplify absolute changes. Firms lean harder on endings and thresholds when moving from €9.99 to €10.49, risking breaching a left‑digit boundary that consumers perceive nonlinearly. Fresh evidence from millions of ride‑hail transactions shows significant demand discontinuities at round numbers, implying strong left‑digit bias in price evaluation. Meanwhile, services inflation—3.3% in the euro area in June—has been stickier than goods, meaning the largest, salience‑rich categories in household budgets remain elevated. Layer in renewed supply frictions: Red Sea disruptions and port congestion pushed container rates to multiples of late‑2023 levels earlier in 2024. However, rates have eased; they remain volatile and above pre‑pandemic norms. The takeaway is structural: higher baselines make pricing more brittle, pass‑through more visible, and consumer reactions more abrupt.

A Stealth Redenomination—Without the Decree

Sustained supply shocks can push the price level up quickly, functioning like a de facto redenomination: not by lopping zeros off currency, but by compressing real purchasing power and re‑scaling everyday numbers. Formal redenominations are rare in advanced economies because they invite confusion and administrative costs; Japan’s and Korea’s recurring debates illustrate the reluctance. Yet the economic effect of a rapid level shift is similar: unit prices, wages, and contracts re‑anchor at higher nominal values, altering behavior even after inflation falls. If doubling freight rates adds around 0.7 percentage points to inflation a year later—and if geopolitical or climate shocks drive repeated spikes—the resulting step‑ups accumulate into a silent re‑scaling. That is why a high price level can erode resilience: future shocks pass through a larger nominal base, reinforcing salience effects and destabilizing pricing conventions that once nudged consumers smoothly across cents and euros.

What the Numbers Mean for Classrooms, Districts, and Ministries

Translate the level arithmetic into operations. Suppose a school district’s 2019 annual food budget was €1,000,000. With a roughly 22% increase in the general price level, holding volumes constant implies about €1,220,000 today before considering composition changes. A new 2% shock translates to €24,400 in extra costs—versus €20,000 had the shock occurred in 2019. Energy‑exposed items behave similarly; if services remain sticky, contracted services (transport, maintenance, catering) will not readily revert. Shipping‑cost surges feed goods inflation with lags; IMF research suggests a doubling of freight rates raises headline inflation by about 0.7 percentage points a year later. For administrators, that means: lock in longer‑dated supply contracts with flexible freight clauses; add contingent reserves to budgets calibrated to price‑level bands rather than point inflation forecasts; and avoid psychologically awkward price thresholds in tuition and fees that risk demand cliffs. For education ministries, benchmarking grants and capitation formulas to price‑level indices—rather than year‑ahead inflation alone—better protects real operations when shocks hit late in the fiscal year.

Beyond Interest Rates: A Price‑Level Resilience Blueprint

The next episode requires broadening the toolkit. First, adopt a “shock‑sensitive target band” that conditions near‑term policy on deviations of the price level from a pre‑shock trend, not just the inflation rate; this preserves credibility while recognizing that level overshoots leave lasting budget scars. Second, build automatic supply‑shock stabilizers on the fiscal side: time‑limited energy VAT buffers, freight‑surcharge offsets tied to observable shipping indexes, and targeted transfers financed by temporary windfall‑profit mechanisms where margins spiked during the last episode. Third, harden the supply side that proved brittle: diversified sourcing and pre‑agreed logistics contingencies for public procurement; strategic inventories for critical education inputs; and standing agreements that index specific contracts to broader cost composites rather than single volatile inputs. Finally, strengthen data for faster, finer policy. Real-time dashboards for services inflation and negotiated wages—now cooling in the euro area—should trigger pre-specified fiscal and regulatory responses, reducing the need for last-second monetary sprints.

Objections—and Why They Miss the Point

One objection says levels are irrelevant if incomes adjust. But wage catch‑up is partial and uneven, and stickier service prices keep real purchasing power fragile even as headline inflation normalizes. Another claim: in the last disinflation, expectations stayed anchored—so sprinting works. That begs the question: anchored expectations coexisted with a level step‑up driven by supply; the same anchor will not shrink the base that amplifies future shocks. A third worry is over‑engineering: “Let rates handle it.” Yet the empirical record shows shipping and supply shocks feed inflation with long lags and persistence; relying on late monetary tightening forces households and public services to absorb large nominal jumps before policy bites. A final critique warns that price‑level tools edge toward bygone regimes. The proposed band is not rigid level targeting; it is a contingency overlay that acknowledges the lived costs of higher baselines while preserving rate‑setting flexibility when services and wages behave differently from goods.

The Next Sprint Starts Now

We learned an important lesson: it is possible to disinflate without engineering mass unemployment. But we also knew that post‑pandemic prices settled on a new plateau. On that plateau, a “tiny” percentage change throws off bigger nominal jolts, consumers react more sharply around round numbers, and firms’ pricing conventions become more complicated to manage. The next episode of high inflation—likely supply‑led again—will test whether we adapted our framework or got lucky once. The prudent course is to hard‑wire price‑level resilience: policy bands that consider the level we live with, fiscal stabilizers that buffer freight and energy shocks, and procurement rules that acknowledge salience and thresholds. If we prepare those cushions now, the next shock need not force another desperate sprint. Our systems—classrooms, clinics, and households—will feel the bump, but they will not lose their footing.

The original article was authored by Kristin Forbes and Jongrim Ha M. Ayhan Kose. The English version of the article, titled "The post-pandemic disinflation: Low sacrifice, high prices," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2024). Annual Economic Report 2024. Basel: BIS. Emphasizes goods‑led disinflation with persistent services inflation.

Bernanke, B., & Blanchard, O. (2024). An Analysis of Pandemic‑Era Inflation in 11 Economies. Brookings Papers / Working Paper 91. Concludes early inflation was driven by relative price shocks, not a wage‑price spiral.

Bernanke, B., & Blanchard, O. (2025). “What Caused the US Pandemic‑Era Inflation?” AEJ: Macroeconomics, 17(3), 1–35.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2025). CPI Home. U.S. CPI rose 2.7% y/y in June 2025.

Drewry (2025). World Container Index. Composite rate $2,517/FEU on July 24, 2025; elevated vs. pre‑pandemic averages.

ECB (2023). “How have unit profits contributed to recent euro area inflation?” Economic Bulletin Box. Documents strong unit‑profit contribution in early phase.

ECB (2024). “Profit indicators for inflation analysis considering the role of total costs.” Economic Bulletin Box. Provides decomposition of costs and margins.

Eurostat (2025a). “Inflation in the euro area—Statistics Explained.” Euro area inflation 2.0% in June 2025; services at 3.3%.

Eurostat / ECB Data Portal (2025b). HICP overall index. Monthly HICP for euro area (2015=100). Jun 2025 ≈ 129 vs. Dec 2019 ≈ 106.

IMF (2025). World Economic Outlook (April 2025). Global inflation projected to fall toward 4.5% in 2025; advanced economies near target sooner.

IMF – Carrière‑Swallow, Y., Deb, P., Furceri, D., Jiménez, D., & Ostry, J. (2022). Shipping Costs and Inflation. IMF Working Paper 22/61. A doubling of shipping costs raises inflation ~0.7 percentage points, peaking after a year.

Minneapolis Fed (2025). Consumer Price Index, 1913–. Index levels imply ~26% cumulative U.S. CPI increase since 2019.

Reuters (2024). “Singapore port congestion shows global ripple impact of Red Sea attacks.” Documents delays and rising rates.

Reuters (2025). “Euro zone wage growth slowing as expected, ECB data shows.” Negotiated wage growth 4.6% in 2024, projected 3.2% in 2025.

Sokolova, T., Seenivasan, S., & Thomas, M. (2023). “More Than a Penny’s Worth: Left‑Digit Bias and Firm Pricing.” Review of Economic Studies, 90(5). Evidence of large demand discontinuities at round‑number thresholds.

VoxEU/CEPR (2025). “The post‑pandemic disinflation: Low sacrifice, high prices.” Synthesizes cross‑country evidence on disinflation with high price levels.

VoxEU/CEPR (2024). “Demand versus supply: Drivers of the post‑pandemic inflation and interest rates.” Finds supply shocks drove much of the post‑pandemic price surge.

FreightWaves (2024). “Container spot rates rocket even higher as Red Sea crisis drags on.” FBX indices surged on Asia–Europe lanes

Comment