The Basel Opt‑Out That Made the World Less Safe: Why America’s refusal to finish Basel III is exporting instability to everyone else

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

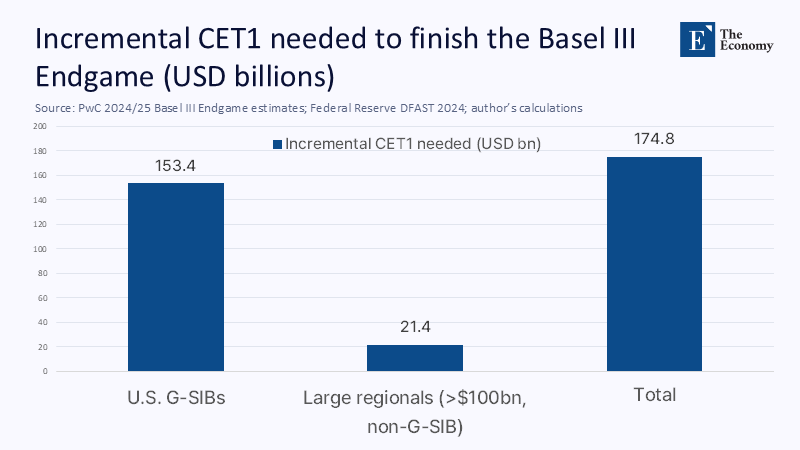

The United States banking sector, with approximately $1.3 trillion in loss-absorbing capital, has effectively halted a plan to raise large-bank requirements by about 20% to comply with the final phase of Basel III. The Fed’s July 2025 conference, led by the new vice chair for supervision, indicated a political willingness to relax rules that had already been diluted. Meanwhile, nearly 44% of US commercial banks relied on reciprocal deposits as of the end of 2023, a clear sign of funding fragility that Basel was designed to address. The numbers do not align with the narrative. The marginal macroeconomic cost of higher capital, which has been consistently assessed as small and outweighed by the stability benefits, has been reinterpreted by banks as existential and accepted as negotiable by key US policymakers. If the United States does not complete Basel, the rest of the world will bear the risk. The issue is no longer just about calibration; it is about credibility, comparability, and cross‑border contagion. The United States is transforming the global safety net into a patchwork of programs. This choice carries significant implications, now more than ever.

Reframing the fight: This is about international reliability, not domestic inconvenience.

The current US debate has been framed as a narrow cost–benefit exercise: Will a 15–20% hike in large-bank risk-weighted assets meaningfully reduce lending or economic growth? That framing obscures the deeper issue. Basel is an international standard designed to ensure comparability of bank resilience, prevent regulatory arbitrage, and reduce the likelihood that one jurisdiction’s leniency becomes everyone’s crisis. When the world’s systemically pivotal banking system decides to diverge—or delay—the signal transmitted to markets, supervisors, and counterparties is unambiguous: global rules are optional, and home politics trump shared prudence. The CEPR economists who have recently re-examined the “Basel Endgame” stress that two separate questions became conflated: whether the US should adhere to international standards, and whether it should raise capital for large banks. Untangling them clarifies the stakes. The first is about trust and coordination; the second is about calibration. By refusing the first, the US undermines the very basis on which it hopes to debate the second. However, by embracing international standards, the US can pave the way for a more stable and prosperous future.

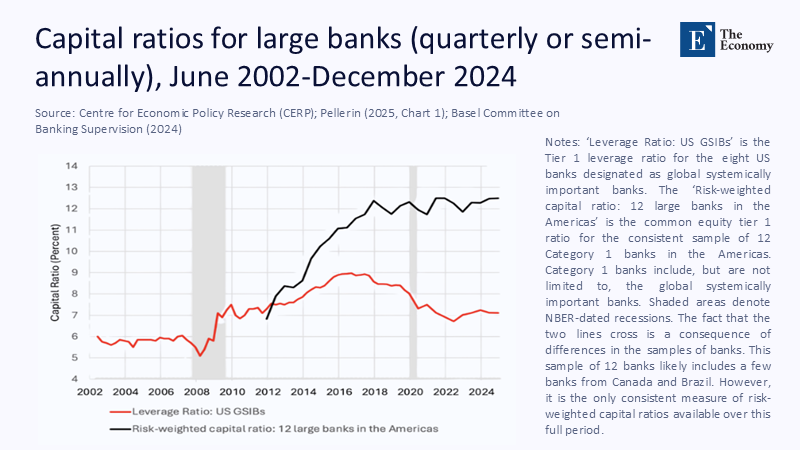

The data the industry does not want to dwell on (and how we infer what’s missing)

The precise macroeconomic effects of higher capital depend on the modeling choices. However, three contemporary facts are hard to dismiss. First, Basel Committee literature surveys continue to find positive net macroeconomic benefits across a broad capital spectrum, suggesting earlier impact estimates were conservative. Second, the Federal Reserve’s 2024 stress tests again showed that the largest banks would remain well capitalized after severe losses—proof that tougher buffers can be met, not that they are unnecessary. Third, FDIC-insured deposits fell 4.8% in the year to June 2023, marking the first such decline since 1995, indicating that deposit stickiness is weaker than many pre-SVB models had assumed. Taken together, this suggests that (a) we should value cross‑jurisdictional consistency more, not less; (b) measured to the broader economy, raising capital on the order contemplated by the Basel Endgame is well within the historical net‑benefit range; and (c) funding fragility is still with us, so capital—and liquidity—are complements, not substitutes. Where sector-wide numbers are missing for 2025, we extrapolate using the PwC estimate that G-SIB capital requirements would rise by ~21% versus ~10% for regionals under the original US proposal, phased in from July 1, 2025, through June 30, 2028. Suppose we apply historical BCBS long‑term impact elasticities—single‑digit basis points of GDP per percentage point of capital—to that incremental rise. In that case, the implied annual GDP “cost” is tiny relative to the welfare gains from even a modest reduction in crisis probability. The industry’s “too much, too complex” line simply does not survive transparent arithmetic.

The shadow gets darker: Nonbanks, FSOC’s revived powers, and the new perimeter problem

Critics of higher bank capital argue that over‑burdening banks merely pushes activity into the shadows. They are right about the migration—but wrong about the prescription. The answer is not to weaken banks; it is to strengthen the perimeter. In November 2023, the Financial Stability Oversight Council finalized interpretive guidance that restores its ability to designate nonbank financial companies as systemically important, reversing constraints imposed in 2019. Yet, as of mid-2025, markets still do not price a credible expectation that large asset managers, payment firms, or fintech platforms with bank-like maturity transformation capabilities will face Basel-like capital floors or liquidity standards. That asymmetry is policy‑made, not fate. If the US truly worried about activity leaving banks, it would pair full Basel compliance with a robust, risk‑based framework for nonbanks—one that recognizes that a levered liquidity provider that can trigger fire sales can be just as systemically dangerous as a large bank. By reviving FSOC’s SIFI designation power but hesitating to use it, Washington is leaving a credibility gap that markets will eventually exploit.

The political economy of “cost”: Why “minimal” for society feels “maximal” to banks

One reason the banking industry perceives “minimal” social costs as “maximal” private costs is the distribution of these costs across different stakeholders. Raising common equity dilutes returns to shareholders and compresses ROE in the short run. For institutions whose compensation culture remains tightly tethered to ROE and price‑to‑book metrics, the politics are predictable. But that is not a reason to abandon an international standard calibrated to system‑wide gains. Moreover, stress test results demonstrate that banks have already internalized the tools to operate with materially higher capital during downturns. The problem is less economic feasibility and more comparative disadvantage: US banks fear that if they invest heavily in capital while nonbanks and European competitors remain competitive, they will lose market share. This is precisely why the US aligning with Basel—and pushing for multilateral enforcement, including reciprocity on capital floors and the cross‑border treatment of internal models—is not a drag on domestic competitiveness but an insurance policy against a race to the bottom. The Reuters coverage of the Fed’s July 2025 conference underscored the industry’s win in stopping the Basel Endgame as proposed; that “victory” is pyrrhic if it fragments the playing field and increases the implicit subsidy to systemic risk.

Anticipating—and rebutting—the core critiques.

“Higher capital will choke lending at a fragile moment.” Evidence does not support a significant, durable lending contraction from higher capital when phased in over several years. Instead, banks adjust via retained earnings and balance‑sheet mix. The Basel Committee’s updated literature review finds positive net macro benefits over a wide capital range, and the Fed’s stress tests show capital remains ample even under very severe scenarios. If lending is weak, as some July 2025 conference participants asserted, it is more plausibly explained by demand conditions and disintermediation toward private credit, not a few percentage points of extra equity.

“Complexity has gone too far; the rules are unintelligible.” Complexity is a bug—but it is also a choice. The Basel Endgame in the US tried to simplify by restricting the use of internal models and using standardized approaches for operational risk. This is precisely the direction reformers have advocated since the global financial crisis. If banks want simplicity, they should accept higher standardized floors, not press to resurrect opaque model privileges.

“Capital is not the problem—liquidity and supervision are.” False dichotomy. The 2023–2024 deposit run dynamics revealed how quickly uninsured funding can evaporate; liquidity was a crucial factor. But without sufficient loss‑absorbing capital, liquidity backstops only delay insolvency. Basel is a package, not a menu. The idea that liquidity can substitute for capital is a return to pre‑2008 complacency.

“Nonbanks are the real risk; regulate them first.” Yes, nonbanks are a growing locus of systemic risk, which is precisely why the FSOC’s revitalized designation authority should be deployed, alongside a regime that subjects designated nonbanks to capital, margin, and liquidity standards analogous to those of Basel. But that argument does not absolve banks from adopting the international standard. We do not secure one node of the system by weakening another.

A policy blueprint that restores credibility without sacrificing growth

First, finish Basel III in the United States—fully and on a credible timetable. The original US proposal’s phase-in from July 1, 2025, to June 30, 2028, was sensible. If politics demand recalibration, let it be on the margin, not on the principle of international alignment. Second, operationalize FSOC’s revived SIFI designation for nonbanks using transparent, data‑driven thresholds on leverage, liquidity transformation, and interconnectedness, coupled with Basel‑like floors. Third, simplify by standardizing: accept higher, simpler standardized risk weights and capital floors in exchange for fewer internal model games. Fourth, embed reciprocity and comparability: work with the Basel Committee to enforce cross-border disclosure of risk-weighted asset calculations, so that market discipline can verify the numbers. Fifth, tie capital relief to proven risk transfer: if banks can demonstrate that specific exposures are fully hedged and cleared through resilient CCPs, allow targeted relief; if not, capital must stay. Finally, reprice the public subsidy: impose a systemic stability levy on institutions—whether banks or nonbanks—that decline to meet Basel-equivalent standards, earmarking the proceeds to pre-fund future resolution costs. This blueprint does not ask the United States to out‑tighten the world; it asks it to keep the promise it made to the world.

If Washington won’t close its capital gap, the rest of us will pay the margin call

We began with a simple asymmetry: the world’s most systemically important banking system has the capital to comply with a global standard, but not the political will. The $1.3 trillion cushion US banks brag about today is precisely the reason they could absorb the incremental capital that Basel III demands. The 20% increase for the largest banks is not a threat to growth; it is a down payment on global stability at a time when nonbanks, fintechs, and private credit funds are testing the edges of the regulatory perimeter. If the United States delays again, the eventual crisis subsidy will be socialized—across borders, across taxpayers, across generations—just as it was in 2008. The endgame is indeed inevitable, but it can arrive either as a negotiated standard or as a market verdict. The former is cheaper. The choice is Washington’s; the consequences are everyone’s.

The original article was authored by Stephen Cecchetti, Rosen Family Chair in International Finance at Brandeis International Business School, Brandeis University, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Basel endgame: Bank capital requirements and the future of international standard setting," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bank for International Settlements / Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2010). An assessment of the long-term economic impact of stronger capital and liquidity requirements (BCBS 173).

Bank for International Settlements / Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2018). The costs and benefits of bank capital: a review of the literature (Working Paper 37).

Cadwalader. (2025, July 10). Federal Reserve Releases Results of Stress Tests.

Cecchetti, S. G., et al. (2025). Basel Endgame: Bank Capital Requirements and the Future of International Standard Setting (CEPR DP20386).

CEPR VoxEU. (2025, July). Basel endgame: Bank capital requirements and the future of international standard setting.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. (2024). 2023 Summary of Deposits Highlights.

Federal Reserve Board. (2024, June). Dodd‑Frank Act Stress Test: 2024 Results.

Financial Stability Oversight Council (US Treasury). (2023, Nov. 17). Guidance on Nonbank Financial Company Determinations.

US Department of the Treasury. (2023). FSOC Designations: Interpretive Guidance.

Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. (2024). Reciprocal Deposits and the Banking Turmoil of 2023.

PwC. (2024/2025). Basel III Endgame: The next generation of risk‑weighted assets.

Reuters. (2025, July 22–23). Big banks audaciously try to thread capital needle; Fed officials, banking experts discuss regulatory rewrite effort at conference.

Wharton Initiative on Financial Policy & Regulation (WIFPR). (2024, Nov. 7). WIFPR Roundtable on Basel III Endgame; (2024, Apr. 5). Basel III Endgame was inevitable for large banks, but what about nonbanks and smaller banks?

Comment