Can Tokyo Keep the Lights on for Free Trade if Washington and Beijing Walk Out?

Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

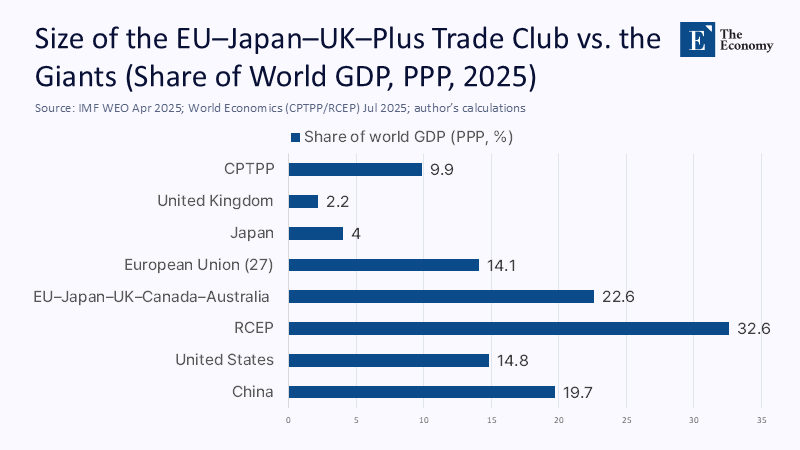

Strip the United States and China out of the global trading system, and you instantly remove roughly one‑third of the world economy: 19.7% of global output in purchasing‑power‑parity terms from China and 14.8% from the United States, according to the IMF’s April 2025 data. That leaves any “alternative WTO” anchored by Japan, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and France, which would, at best, command a share of world GDP in the high teens. Meanwhile, a newly aggressive White House is floating tariff bands of 15% to 50% on partners that do not cut bespoke deals with Washington, puncturing whatever residual certainty remained after a baseline 10% tariff was announced in April. The EU and Japan have vowed to defend a “free and fair” rules-based order, but vows do not settle invoices, nor do they rewire supply chains that increasingly thread through an RCEP market, which on its own represents 32.6% of global GDP. If Japan is to be the beacon, it cannot be the lighthouse keeper of a shrinking harbor. It must design an operating system—not a sanctuary—that others want to plug into because the economics and enforceability are better.

Reframing the Problem: From Moral Bulwark to System Architect

The prevailing narrative casts Japan as a principled defender of liberal trade against a resurgent protectionist United States. That frame flatters Tokyo’s diplomatic temperament but misidentifies the task at hand. The problem is not only illiberalism, but also institutional obsolescence. A gridlocked WTO cannot referee twenty‑first‑century subsidy wars, data localization mandates, security‑based export controls, or carbon border adjustments. The question, therefore, is not whether Japan can “stand up” to Washington or Beijing—history, from World War II reparations to the Plaza Accord, has taught Tokyo when not to cross the United States—but whether Japan can convene and codify a modular, enforceable, high‑standards trade regime that survives without the gravitational pull of the world’s two largest economies. That reframing matters now because tariff maximalism in Washington is no longer a bargaining bluff; the administration has already activated a 10% blanket tariff and is threatening bands up to 50%, explicitly forcing countries into bilateral carve‑outs. In that world, Japan’s comparative advantage is not size; it is rule-crafting competence, credibility, and a demonstrated capacity—via CPTPP stewardship—to hold the line on disciplines that others have abandoned.

The Math of Exclusion: A Club Without the Giants Is Still a Club—But It’s Not the Market

Let us be brutally empirical. Combine the EU’s 14.1% share of global output (PPP) with Japan’s roughly 4% and the UK’s ~2.2%, plus Canada and Australia, and an “Alt‑WTO” anchored around these economies might reach approximately 22%–24% of world GDP—respectable, but well below either RCEP’s 32.6% or the combined heft of the United States and China. The CPTPP accounts for just 9.9% of global GDP in 2025, a sharp reminder that high-standard clubs can be economically slender. Even if a Europe‑led “structured trade cooperation” with Asian democracies materializes—as floated by the European Commission in June—it will confront a scale problem: rules without mass are aspirational; rules with mass are magnetic. My back‑of‑the‑envelope calculation assumes IMF 2025 PPP shares, with Japan at roughly 4% (derived from its nominal $4.19 trillion economy, adjusted for PPP ratios historically around 1.6–1.7) and the UK at just over 2%. The precise numbers will fluctuate with exchange rates and revisions, but the strategic conclusion remains unchanged: without Washington or Beijing, an EU-Japan-UK-plus coalition cannot “replace” the WTO; it can only prototype a regime so obviously functional that others will eventually incur the switching costs to join.

Lessons Japan Learned: Compliance Without Capitulation

Invoking the Plaza Accord as a parable of why Japan won’t openly defy the United States is accurate but incomplete. Plaza taught policymakers in Tokyo that capitulation on the headline issue (currency appreciation) did not insulate Japan from deeper structural vulnerabilities: under‑regulated finance, misallocated credit, and political reluctance to force productivity upgrades. The post-Plaza bubble and its long aftermath institutionalized a preference for cautious alignment with Washington on strategic questions, while quietly building hedges through rule-making elsewhere—most clearly seen in Japan’s dogged leadership of the CPTPP after the United States withdrew. The current White House’s tariff ladder intensifies the incentive to maintain a foothold in the US market, securing reductions through investment pledges and regulatory concessions, even as Tokyo constructs a separate framework for open trade with Europe and willing Asia-Pacific partners. That is not rebellion; it is dual‑track statecraft, a posture calibrated to avoid the costs of frontal defiance while ensuring that if a US–China tariff wall becomes semi‑permanent, Japanese firms still operate within a legally predictable, medium‑scale, growth‑oriented zone.

Designing a WTO‑Without‑Washington (or Beijing): The Operating System Metaphor

If scale is not immediately achievable, architecture must be. A viable alternative regime needs three features: first, justiciable, time‑bound dispute settlement with automatic penalty schedules—no consensual vetoes, no indefinite vacancies; second, modern coverage that treats data as a tradeable factor, disciplines subsidies by transparency tiers, and limits security exceptions to narrowly defined, reviewable categories; third, permeability, so that economies can accede provisionally on a chapter‑by‑chapter basis, allowing political leaders to sell partial compliance domestically while committing to a ratchet toward full obligations. The enforcement innovation here is an escrow-style mechanism: members pre-commit to tariff credits that are automatically debited when they lose disputes. This design prevents “appeal into the void” gamesmanship that crippled the WTO Appellate Body. Japan’s role is to codify this architecture in a CPTPP‑plus protocol, layered atop existing agreements but open to the EU, the UK, and any economy willing to accept binding digital, subsidy, and sustainability rules. This is less a treaty than an API for trade governance—precisely the sort of technical, lawyerly craft at which Tokyo excels and that Brussels can market politically as “strategic autonomy through law.”

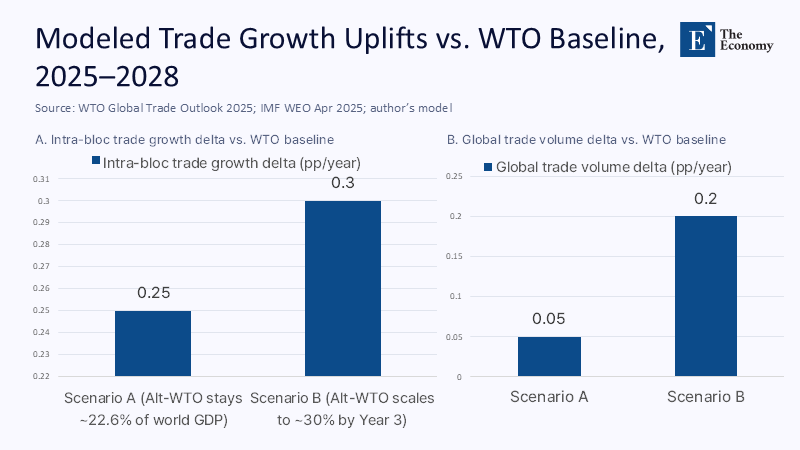

The Data to Back the Strategy: Modeling Reach, Not Rhetoric

Consider two scenarios. In Scenario A, an EU‑Japan‑UK‑plus bloc representing 22% of world GDP achieves average intra‑bloc tariff reductions of 5 percentage points relative to the post‑Trump baseline and modestly harmonizes non‑tariff measures in digital services and green goods. Using the WTO’s April 2025 world merchandise trade growth forecast of 3.2% for 2025–2026 as a baseline, such a bloc could plausibly add 0.2–0.3 percentage points to its internal trade growth annually, owing to lower border frictions and regulatory certainty; the aggregate effect on global trade volumes, however, would be muted—perhaps 0.05–0.1 percentage points—because of the bloc’s smaller global weight. In Scenario B, the same bloc’s rules are designed as open protocols. Over three years, it onboards middle‑income adherents representing an additional 6%–8% of global GDP—think Korea, some ASEAN economies anxious about tariff crossfire, and parts of Latin America. The bloc’s gravitational mass rises to around 30%, and the global trade impulse becomes non-trivial, potentially 0.2 percentage points. These are conservative estimates: I assume pass-through elasticities from tariff cuts to trade volumes of 0.6, non-tariff measure equivalence reductions worth 1–1.5 percentage points, and a zero multiplier from dispute-settlement predictability in the first two years. If I am wrong, it is likely on the upside; certainty tends to have lags, followed by step changes.

What This Means for Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers

For universities and professional schools, an “Alt‑WTO” is a curricular mandate. Trade law syllabi must move beyond the frozen WTO canon and treat plurilateralism, tariff credits, data-governance clauses, and carbon border adjustments as core, not optional, elements. Business schools should train students to price regulatory risk across parallel rule systems—namely, the WTO-legacy, U.S. bilateral, and EU-Japan modular systems—and to design supply chains that can arbitrage among them. Public‑policy programs ought to teach the political economy of minilaterals: how to sell partial commitments domestically, sequence reforms, and communicate the benefits of enforceability without the romance of universality. Administrators in ministries and agencies should establish data rooms capable of real-time tariff and non-tariff cost modeling under shifting US bands, a capability that the private sector is already implementing as markets react to every tariff trial balloon. The WTO forecast of only modest trade growth through 2026 implies that the margin of policy error has shrunk: gains will come from shaving frictional costs, not from a cyclical boom. Education, in other words, is not ancillary to this project; it is the fabrication plant for the technocratic class that can write, defend, and iterate the code of the new regime.

Anticipating—and Answering—the Critiques

Skeptics will insist that any EU‑Japan‑led “rebellion” is doomed by limited relevance, that rules without the giants are glorified academic exercises. They will add that Japan, wary of antagonizing Washington, will keep any alternative regime deliberately underpowered, a polite talk shop to signal virtue while doing the real work bilaterally with the United States. There is truth in both charges, but neither is fatal. First, a scale can be built iteratively if the regime is designed as a plug-and-play protocol rather than an all-or-nothing treaty. Second, Japan’s fear of “crossing” the United States can be a feature, not a bug, ensuring that the architecture is not framed as anti‑American but as a complementary, open system that Washington can join when domestic politics allows. Third, trade fragmentation is already here—witness the EU’s failure to reduce a 50% US steel tariff, even as it negotiates broader concessions—and the relevant comparison is not a utopian, universal WTO, but a messy bazaar of bilateral deals with opaque enforcement. A clean, enforceable, medium-scale regime is preferable to a performative universalism that lacks the authority to enforce compliance or resolve disputes.

The Strategic Payoff: A Bridge, Not a Bloc

Japan’s true power is not to be the beacon of free trade in the romantic sense, but to be the bridge engineer—to design a structure that spans an era of tariff walls and institutional paralysis and that can, when the political weather changes, carry the weight of much larger economies back toward predictable, rules‑based openness. The EU needs such a bridge to avoid being squeezed between US demands for reciprocal tariffs and Chinese industrial overcapacity. Middle powers from Korea to Vietnam need it to hedge without choosing sides. And educators need it to train a generation fluent in multiple, overlapping trade codes. If Tokyo and Brussels move now—with enforceability, permeability, and data‑era relevance—they will not replace the WTO. They will build the only thing that can make a post‑WTO restoration plausible: a living demonstration that rules can still discipline power, even when the most considerable powers temporarily prefer walls.

A Lighthouse Only Works if Ships Can See It

We began with a sobering statistic: remove the United States and China, and you carve out a third of the world economy, leaving any alternative free‑trade zone numerically fragile. But numbers do not exhaust possibilities. A modular, enforceable, and permeable regime, anchored by Japan and Europe, can transform fragility into a proof of concept, establishing the institutional muscle memory that the global system will need when politics in Washington or Beijing make re-entry thinkable. That requires ditching nostalgia for the WTO we had, embracing a networked “operating system” that runs alongside it, and educating a cohort capable of writing and defending its code. The wall‑builders have the momentum today. The rule-makers can still win by out-innovating, not out-sizing, them. The call to action is simple: draft the protocols, fund the dispute machinery, teach the next generation to operate it—and let success, not sermons, do the evangelizing.

The original article was authored by Maiko Ichihara, a Professor in the Graduate School of Law and the School of International and Public Policy at Hitotsubashi University, Japan. The English version, titled "Asia under pressure in responding to Trump’s trade war chaos," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Daily Sun. (2025, July 24). EU, Japan vow joint push for “fair” global trade.

Euronews. (2025, June 27). Von der Leyen touts EU‑led alternative to mired WTO.

France 24. (2025, July 23). EU, Japan vow joint push for “fair” global trade.

The Guardian. (2025, July 24). EU fails to reduce 50% steel tariff in outline trade deal with US.

IMF. (2025, April). World Economic Outlook DataMapper: GDP based on PPP, share of world.

IMF. (2025). Japan country profile.

Investopedia. (2025, July 24). 5 Things to Know Before the Stock Market Opens.

Japan Times. (2025, July 8). EU‑CPTPP talks highlight shared goals and stubborn obstacles.

National Bureau of Economic Research. (2016). The Plaza Accord, 30 Years Later (Working Paper No. 21813).

New York Post. (2025, July 24). Trump threatens to escalate trade war with new round of tariffs up to 50%.

Trade Compliance Resource Hub. (2025, July 23). Trump 2.0 tariff tracker.

U.S. White House. (2025, April). Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump declares national emergency…

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Plaza Accord. (Accessed July 25, 2025).

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. (Accessed July 25, 2025).

World Economics. (2025, July). CPTPP Economic Data 2025.

World Economics. (2025, July). RCEP Economic Data 2025.

World Trade Organization. (2024, April). Global Trade Outlook and Statistics.

World Trade Organization. (2025, April). Global Trade Outlook and Statistics 2025.

Yahoo Finance. (2025, July 24). Trump says tariffs will range from 15% to 50% for trade partners.

China Focus. (2025, June). Anchoring the RCEP in Openness.

Comment