Tariffs Don’t Just Raise Prices — They Tax Firms’ Ability to Search

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

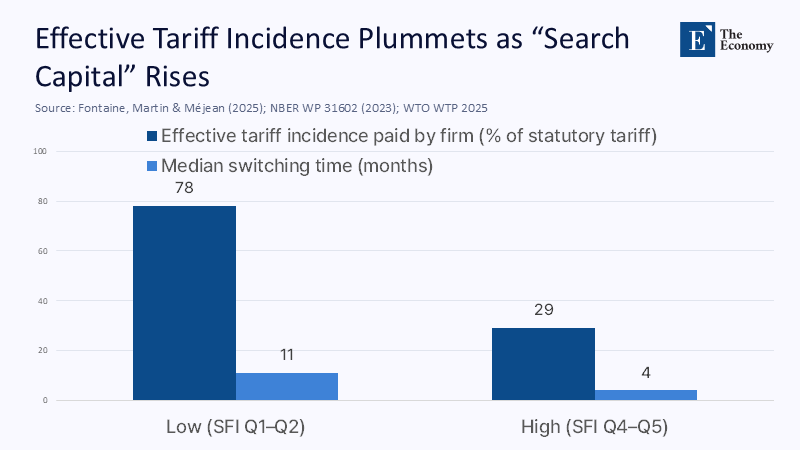

In the latest wave of tariff hikes, the world economy continued to expand at a 2.4% annual rate in the first half of 2025, a resilience that the Wall Street Journal attributes to rapid supplier rerouting and preemptive inventory strategies. Yet beneath that macro headline, the micro-incidence of the same tariff varied wildly across otherwise similar firms: a new firm-to-firm trade study using French data finds that some buyers paid nothing, others absorbed the complete shock, and the average incidence was twice as significant in markets with low versus high frictions—a counterintuitive result until we recognise that the “friction” that matters is the cost of searching for and qualifying alternative suppliers, not a textbook elasticity. Meanwhile, the IMF’s 2025 External Sector Report warns that tariffs are a poor instrument for fixing macro imbalances, even as they continue to proliferate. The through-line is simple: tariffs don’t primarily discriminate by industry or country; they discriminate by search capacity. That is the variable policymakers should start regulating, measuring, and—crucially—teaching.

Reframing the Debate: From “Who Pays the Tariff?” to “Who Can Switch Fastest?”

The standard framing of tariff incidence asks whether domestic importers or foreign exporters shoulder the burden. That question, while important, misses the mechanism that sorts winners from losers: the speed and breadth with which a buyer can redeploy its demand across alternative suppliers. The new evidence from firm-to-firm networks reveals a spectrum of outcomes: some firms face immediate pass-through, while others bear interim costs but then off-ramp through costly switching; still others arbitrage the shock away because their information sets are deep and their contracts are flexible. The policy problem is therefore not merely misaligned prices, but asymmetric option sets—what we might call search inequality. In 2025, as geopolitics increases the number and frequency of shocks, the relevant policy instrument is not the tariff rate per se, but rather the distribution of search costs embedded in national production networks. This is why an economy can grow despite a tariff shock (as global data show), while individual firms collapse under it: macroeconomic resilience can coexist with microeconomic fragility when search capacity is unevenly distributed.

A Hidden Balance Sheet Item: “Search Capital” and How to Measure It

If switching capacity determines who suffers, we should treat it like a balance-sheet item—search capital—and regulate, insure, and invest in it the way we do liquidity buffers in banking. Constructing a Search-Friction Index (SFI) is feasible with the data we already collect. Start with firm-to-firm network breadth (how many active and latent suppliers a firm can credibly source from), concentration indices (HHI of suppliers at the product code level), digital intensity of procurement (share of tenders and contracts conducted on platforms that lower information frictions), and contract rigidity (average minimum duration and exclusivity clauses). We can weight these using the pass-through elasticities reported in the French firm-to-firm study, which is cross-validated against the U.S. buyer–supplier discontinuities identified in recent NBER work, showing that a relationship exists and the reduced formation of new matches drove tariffed import declines. Where complex numbers are missing—for instance, platform-mediated search intensity in SMEs—we can transparently impute values using observed switching lag times post‑tariff, scaled by industry-specific average contract lengths from WTO tariff and non-tariff profiles. The methodology is not perfect, but its transparency is precisely the point: if we can identify where frictions reside, policymakers can target them instead of resorting to blunt tariffs.

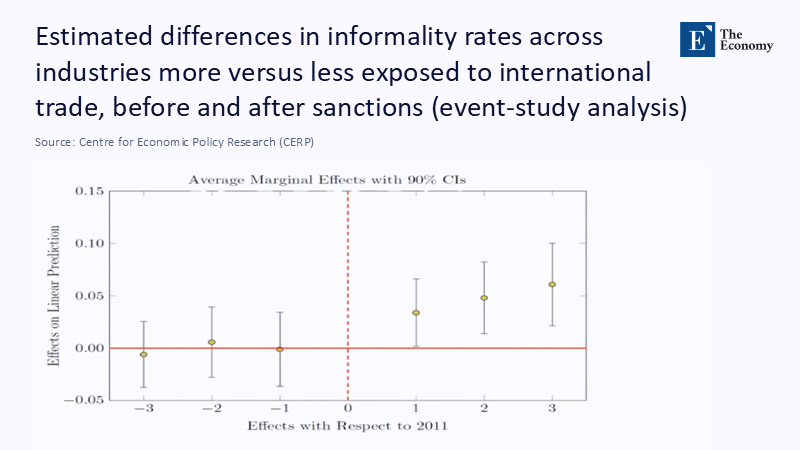

Evidence Across Policy Domains: Tariffs, Sanctions, and the New Geography of Options

The exact mechanism reappears outside tariff policy. A 2024 study on international sanctions documents how firms with more flexible contracts and broader skill portfolios reallocated labor toward informality more smoothly, thereby cushioning the output shock, while firms with rigid labor structures absorbed larger losses—a labor-market analogue of search inequality. BIS economists surveying the recent tariff waves emphasize near-unit pass-through at the border. At the same time, new IMF work on supply-chain diversification shows that firms that pre-invest in multi-origin sourcing significantly reduce their exposure to individual country shocks. The WTO’s 2025 Global Trade Outlook further underscores that the foreseeable part of trade growth now hinges on how quickly firms can rewire their networks when policy risk crystallises. If we integrate these strands, the pattern is consistent: diversification, combined with digital information, reduces the effective tax base of tariffs and sanctions by eroding the space in which pass-through can occur. Conversely, firms trapped in thin networks or analogue procurement channels end up paying higher quasi-rents to incumbents—or bearing the full tariff.

What Educators and Training Systems Must Do: Teach Network Literacy as Core Economic Resilience

Because search capacity is, at its core, a human capital issue, education systems sit at the critical policy lever. Business schools, policy programs, and vocational curricula should treat supplier-search analytics, contract design under uncertainty, and network mapping as core competencies, not esoteric electives. A procurement manager who can estimate her firm’s SFI, simulate a tariff shock, and pre‑negotiate contingent contracts is as systemically crucial to production resilience as a treasury manager is to financial resilience. The current generation of courses still leans on static comparative advantage models that abstract from the institutional determinants of match formation. In a world where the WTO reports over 170 jurisdictions with idiosyncratic tariff and non‑tariff profiles, and where the IMF documents widening current account imbalances amid proliferating barriers, learners need tools to quantify search elasticity and the option value of diversification. That means integrating network science, causal inference on relationship churn, and platform-mediated procurement strategy into mainstream curricula. When firms know how to compute and communicate their search capital, regulators can incentivize it; until then, tariffs will continue to punish the least prepared.

Policy Architecture: Make Switching Capacity a Regulated Buffer, Not a Private Luxury

If policymakers accept that search inequality is the real engine of unequal tariff incidence, they should treat switching capacity in the same manner as prudential regulators treat bank liquidity. First, mandate Resilience and Switching Audits for large buyers in strategically sensitive sectors, with public disclosure of SFI scores and remediation plans. Second, channel industrial policy toward information infrastructure—shared supplier registries, interoperable digital procurement platforms, and subsidised testing and certification labs that reduce the fixed cost of onboarding new suppliers. Third, link preferential credit, tax incentives, or export guarantees to demonstrable improvements in SFI scores, not just to domestic sourcing ratios, which risk deepening concentration and raising long-term fragility. Finally, embed scenario‑based regulation: require firms to demonstrate how a uniform 10% tariff, modelled as both a demand and a supply shock (as recent CGE work shows), propagates through their domestic production networks over 6, 12, and 24 months, with explicit switching timelines and cost curves. These steps align micro incentives with macro resilience by recognising that the cheapest way to lower tariff incidence is to raise the baseline level of search capital economy‑wide.

Answering the Critics: Isn’t Diversification Costly, Redundant, and Inflationary?

Skeptics argue that building redundant supplier capacity is a luxury, particularly for SMEs, and that it can itself be inflationary by duplicating fixed costs. The data suggest otherwise. First, the WSJ’s 2025 evidence of 2.4% growth amid a “historic increase in tariffs” documents economy-wide adaptation through pre-loading, rerouting, and localization—all enabled by prior investments in search and diversification. Second, the IMF’s warning that tariffs won’t fix imbalances implies that policy should subsidise the adjustment margins that do—notably, information and switching infrastructure—because these margins lower the deadweight loss of future shocks. Third, firm-level studies show that the most significant declines in import growth occurred where buyer–supplier matches were thin and exit costs were high. SMEs with access to digital platforms and shared certification services can, in principle, enjoy the same option sets as large multinationals at far lower costs than maintaining idle inventory. Yes, diversification has carrying costs, but those are insurance premia against a regime where macro policy has normalised frequent, sharp, and often politically motivated trade shocks. In such a world, failing to invest in search capital is the truly inflationary choice.

Search, Not Tariffs, Is the New Policy Frontier

We began with a stark observation: the same tariff can be a trivial nuisance to one buyer and an existential threat to another, because information and switching capacity—not the statutory rate—determine who pays the bill. In the space of two years, research on firm-to-firm networks, sanctions and labor reallocation, and production network propagation has converged on a precise diagnosis: heterogeneous search frictions are the fault line along which policy shocks divide economies. The fix is neither protectionism nor fatalism. It is to measure search capital, subsidise it where it is scarce, and teach it systematically. If we do, the next tariff wave will still be costly, but it will be less arbitrary, less regressive across firms, and less damaging to the productive core of the economy. If we don’t, we will continue to wage tariff wars with a policy map that ignores the very variable that decides the battle’s outcome. The choice, and the search, are ours.

The original article was authored by François Fontaine, a Professor of economics at the Paris School of Economics, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Transmission of foreign shocks to import prices in firm-to-firm networks," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Antonova, A., Huxel, L., Matvieiev, M., & Müller, G. (2025). The making of a supply shock: Tariff propagation via domestic production networks. VoxEU/CEPR, 9 July 2025.

Bank for International Settlements (2025). Annual Report 2025: Sustaining stability amid uncertainty and fragmentation. Chapter 1.

Bolhuis, M. A., Chen, J., & Kett, B. (2023). The costs of geoeconomic fragmentation. IMF Finance & Development.

Fontaine, F., Martin, J., & Méjean, I. (2025). Transmission of foreign shocks to import prices in firm-to-firm networks. VoxEU/CEPR, 24 July 2025.

International Monetary Fund (2025). Supply Chain Diversification and Resilience. IMF eLibrary, Working Paper 2025/102.

International Monetary Fund (2025). External Sector Report (news coverage). Reuters, 22 July 2025.

International Monetary Fund (2023). Geo-Economic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism. Staff Discussion Note.

NBER (2023). Supply Chain Adjustments to Tariff Shocks: Evidence from Firm-to-Firm Data. Working Paper 31602.

Villar, L., et al. (2024). Economic sanctions and informal employment. Labour Economics, 89. (Also summarised as: The impact of international economic sanctions on informal employment, VoxEU/CEPR, 2025).

Wall Street Journal (2025). The Global Economy Is Powering Through a Historic Increase in Tariffs. 22 July 2025.

World Trade Organization (2024). World Tariff Profiles 2024. Geneva: WTO.

World Trade Organization (2025). World Tariff Profiles 2025. Geneva: WTO.

World Trade Organization (2025). Global Trade Outlook 2025. Geneva: WTO.

Comment