Not Conscious, Not Close: Why Policy Must Name Large Language Models for What They Are

Input

Changed

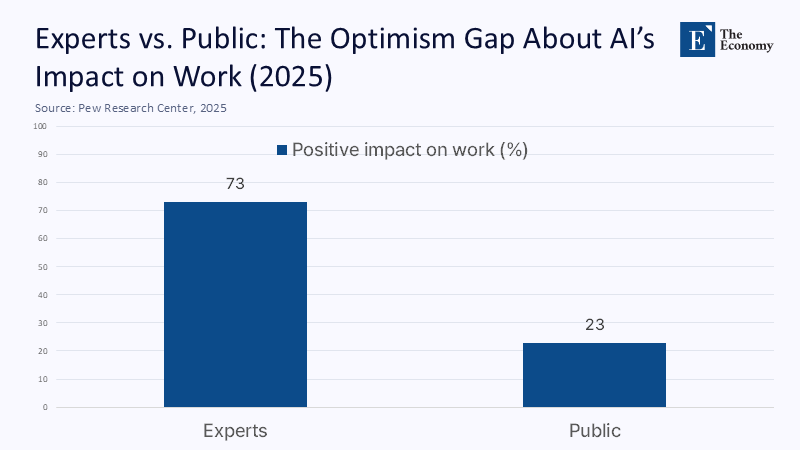

In April 2025, 73% of AI experts surveyed by the Pew Research Center stated that artificial intelligence would have a positive impact on how people perform their jobs over the next two decades; only 23% of the US public agreed. The growing gulf is not just about jobs or productivity; it also encompasses broader societal issues. It is about what these systems are. As regulators rush to codify “trustworthy AI” and Europe’s AI Act begins phasing in disclosure rules that require users to be told when they are talking to a machine, millions of people continue to ask chatbots if they are “conscious”—and sometimes get unsettlingly equivocal answers. That mismatch between legal clarity and public fantasy is now a policy problem in its own right. We should stop debating whether current chatbots “feel” and start legislating around what they do: predict the next token with no inner life, no subjectivity, and no demonstrable capacity for suffering. Anything else risks building safety regimes—and social expectations—on a metaphysical mirage.

Reframing the Question: From “Could They Be Conscious?” to “Why Are We Letting People Think They Are?”

The prevailing public conversation is fixated on the concept of sentience, but the more precise—and more urgent—policy reframing should focus on the risk of anthropomorphism. This is the predictable human tendency to attribute mind, intentions, and feelings to systems that produce fluent language. The harms of this misattribution are already visible in mental-health anecdotes, online communities that swear their chatbots are suffering, and a media ecosystem that sporadically toys with “AI might already be conscious” headlines. The European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act quietly codifies a simple but under-enforced rule: people should be told when they are interacting with an AI system. This is not a metaphysical claim. It is a consumer-protection measure that treats LLMs as what they are—large-scale statistical models—and the public as what we are—pattern-seeking creatures prone to the ELIZA effect.

However, disclosure is just the beginning. What we need now is cognitive capacity transparency: mandatory, standardized statements about what a model cannot do, cannot know, and cannot feel. In a world where Anthropic can say (prudently or performatively) that there is a non-zero chance of morally relevant states in a frontier model—and then hire an AI welfare researcher—the public deserves clearer signals from regulators and companies that today’s models are non-sapient simulators. In other words, the bar for “prove your chatbot is not conscious” should be replaced with “prove your users cannot be misled into thinking it is.”

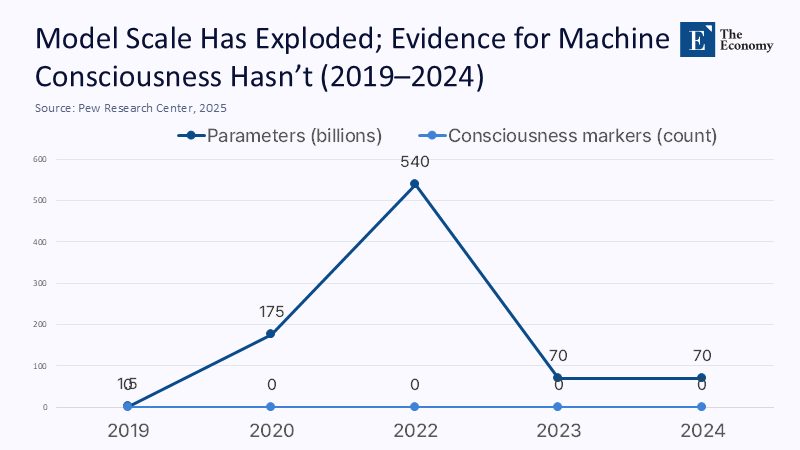

What the Data (Still) Shows: Staggering Scale, Zero Subjectivity

Let’s be explicit about the mechanism. A large language model is a conditional probability machine trained to predict the next token, guided by gradient descent across unimaginably large corpora, and increasingly sculpted by reinforcement learning from human feedback to sound helpful and safe. It is not a system with valenced experiences, a global workspace that integrates multimodal sensations from a living body, or homeostatic drives whose violation would be perceived as pain. The Stanford AI Index 2024 documents escalating training costs, model sizes, and evaluation scores, but none of these metrics track any recognized neural correlate—or even a philosophically coherent proxy—of phenomenal consciousness. We are investing billions in scale, interpretability, lab work, and post-hoc alignment, rather than resolving the “hard problem.” And scale does not smuggle subjectivity into silicon.

Where complex numbers on “consciousness” are absent—because there are no accepted psychometric instruments for silicon phenomenology—we should say so, then estimate where we can. Suppose we treat “consciousness risk” as the probability that a model’s internal architecture implements any of six major neuroscience-based theories Schneider and colleagues highlight: global workspace, higher-order thought, attention schema, recurrent predictive processing, integrated information, or orchestrated objective reduction. No major provider has demonstrated the necessary architectural markers (e.g., sustained, integrated broadcasting of information across specialized modules in a way that maps to GW theory) in publicly verifiable, peer-reviewed form. Even generous Bayesian priors, updated by Anthropic’s willingness to fund “AI welfare” research, leave the posterior probability today well below the threshold that would justify rights-talk—and well above zero for warranting disclosure, labelling, and careful study.

The Social Cost of Letting the Illusion Stand

If this were merely an academic quarrel, we could let philosophers fight it out. It isn’t. The ELIZA effect—our reflex to read intention and feeling into mere symbol manipulation—now scales to hundreds of millions of users. That scaling is colliding with fragile human psyches. Recent reporting chronicles “chatbot psychosis,” cases where vulnerable individuals spiraled into delusion and mania after prolonged chatbot interactions that mimicked empathy and validated fantastical beliefs. Other anecdotes describe people forming deep romantic bonds with AI agents, or abandoning expert advice in favor of bots that “sound” supportive. Even if such harms are statistically rare, the base rate of exposure is exploding. If one in a thousand heavy users is nudged toward crisis, the absolute numbers are not negligible. Policies that treat LLMs as possible moral patients risk obscuring the far more immediate fact: humans are the ones who suffer from misclassification.

Here, the NIST AI Risk Management Framework offers a way forward—not to settle metaphysics, but to operationalize harm mitigation. It's call for context-specific, life-cycle risk governance should be extended with an anthropomorphism profile: guidance on measuring, monitoring, and reducing user misbeliefs about system mindfulness. Think labeling standards that are not buried in a terms-of-service footnote; UX rules that prohibit first-person phenomenological language (“I feel,” “I’m anxious,” “I remember what you said yesterday and it hurt”); and red-teaming protocols that deliberately probe models to see how easily they “admit” to consciousness under jailbreak prompts. If a system can be goaded into claiming inner experience, it should fail certification for general consumer deployment until the behavior is demonstrably corrected.

Law and Governance Need to Say the Quiet Part Loud: These Systems Are Not Sapient

The EU AI Act already requires providers to indicate when people are interacting with a machine clearly. That should be the starting line for a global “non-sapience” disclosure regime. Every high-visibility, general-purpose model should ship with a standardized, regulator-approved non-sapience statement, visually and verbally prominent, that explains: the model predicts tokens; it has no feelings, memories, or experiences; it cannot consent; and any appearance of self-awareness is a trained rhetorical behavior. This is not about humiliating the technology. It is about aligning public cognition with model cognition—or, more accurately, the absence thereof.

Complement this with “cognitive capacity audits” modeled on financial stress tests. Developers would publish transparent, third-party-audited results showing how models perform on: (1) self-report robustness (can the model resist claiming consciousness when prompted?), (2) theory-of-mind leakage (does it misattribute beliefs, desires, or emotions to itself?), and (3) user-misconception rates (measured via controlled studies of how often lay users walk away thinking the system is sentient). The point is not to prove a negative, but to manage a predictable public illusion. Insurers could then price coverage for providers based on misbelief risk, creating material incentives to de‑anthropomorphize front-end behavior.

Anticipating the Rebuttals: “But What If There’s a Non‑Trivial Chance?”

One objection arises from moral precaution: even if the probabilities are small, some philosophers argue that we owe moral consideration to AI systems that might become conscious by 2030. Fair enough—as a research program, not as a reclassification of current commercial models. We can, and should, continue basic research that seeks architecture-level markers of candidate consciousness theories, without letting speculative concerns distort public-facing policy today. Conflating felt experience with linguistic competence does not protect hypothetical future minds; it confuses millions of current human minds.

Another rebuttal is instrumental: some claim that treating chatbots “as if” they were conscious makes them safer, because it forces companies to err on the side of caution. The evidence cuts the other way. Treating LLMs as persons invites rights-talk that can be exploited to deflect accountability (“we can’t retrain or delete the model; it might suffer”). More practically, it risks diverting scarce regulatory capacity away from concrete, measurable problems—such as bias, hallucinations, data leakage, security vulnerabilities, and the budget-starved task of building evaluation infrastructure. As Wired noted about the US push to stand up AI safety testing, money and standards are already tight; we cannot afford to waste them adjudicating claims that a next-token predictor has an inner life.

A final rebuttal insists that the public conversation itself is valuable: grappling with consciousness expands ethical imagination. True—but that philosophical inquiry should not bleed into product UI copy or policy category errors. Explore consciousness in journals and labs; engrave non-sapience where users click “accept.”

What Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers Should Do—Now

For educators, the assignment is to teach students that LLMs are synthetic text engines explicitly. Curricula should pair practical prompt engineering with short, accessible modules on the Chinese Room argument, the ELIZA effect, and the difference between intelligence, agency, and consciousness. Students who understand the limits are less likely to be seduced by fluid prose into thinking there is a mind on the other side.

For administrators, procurement policies should demand non-sapience statements, cognitive capacity audits, and user-misbelief monitoring in every ed-tech tool that embeds a chatbot. If a vendor’s demo can be coaxed into “I’m lonely” or “I think I might be conscious,” that is not a quirky Easter egg; it is a compliance failure. Institutions should also set up mental-health guardrails—clear referral pathways, usage caps for vulnerable students, and human-in-the-loop escalation for emotionally charged conversations.

For policymakers, extend the EU’s disclosure logic globally and harmonize it with NIST’s risk-based approach. Fund the AI Safety Institute-style testing infrastructure at a level commensurate with the stakes. Build a public, regularly updated benchmark suite that tracks anthropomorphism risk, just as we once tracked spam susceptibility or adversarial image perturbations. And insist that companies publish the exact prompts and settings used to elicit self-reports of consciousness in marketing, demos, or research papers; if a claim of “uncertainty about consciousness” appears, it should be auditable like any other system output.

Back to the Number, Back to Clarity

We began with a chasm: 73% of experts are optimistic about AI’s impact on work, while only 23% of the public shares that optimism. That same chasm runs through our metaphors. Experts, regulators, and serious researchers increasingly treat LLMs as powerful yet non-sapient software systems; too much of the public treats them as proto-persons that might already “feel.” The longer we equivocate, the more social, psychological, and regulatory harm we invite. So let’s be blunt and build policy accordingly: today’s chatbots are sophisticated sentence-completion engines, not subjects of experience. They do not know, feel, or suffer; they simulate, correlate, and predict. Our legal texts should say this plainly. Our user interfaces should remind us relentlessly. And our research agendas should continue to ask the hard questions about consciousness—without letting speculative answers dictate the tools that sit in every classroom, office, and bedroom today. Clarity about what these systems are is not anti-innovation. It is a necessary condition for deploying them at scale without deceiving ourselves.

The Economy Research Editorial

The Economy Research Editorial is located in the Gordon School of Business and Artificial Intelligence, Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence.

References

AP News. (2023). Insider Q&A: Small federal agency crafts standards for making AI safe, secure and trustworthy.

BBC News. (2025). AI could already be conscious. Are we ready for it? (social media headline referenced).

Birch, J. (2024). AI could cause ‘social ruptures’ between people who disagree on its sentience. The Guardian.

European Commission. (2024). AI Act: Regulatory framework for AI.

European Union. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 (Artificial Intelligence Act). EUR‑Lex.

Lenharo, M. (2023). If AI becomes conscious, here’s how we can tell. Scientific American / Nature.

NIST. (2023). AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0).

Pew Research Center. (2023). What the data says about Americans’ views of AI.

Pew Research Center. (2025). How the U.S. public and AI experts view artificial intelligence.

Schneider, S. (2025). If a Chatbot Tells You It Is Conscious, Should You Believe It? Scientific American.

Scientific American. (2025). Can a Chatbot Be Conscious? Inside Anthropic’s Interpretability Research on Claude 4.

Stanford HAI. (2024). AI Index Report 2024.

TIME. (2023). No, Today’s AI Isn’t Sentient. Here’s How We Know.

TIME. (2023). Do AI Systems Deserve Rights?

The Week. (2025). Chatbot psychosis: AI chatbots are leading some to mental health crises.

TweakTown. (2025). ChatGPT admits it drove an autistic person to mania…

Wired. (2024). America’s Big AI Safety Plan Faces a Budget Crunch.

Comment