The War Bill That Won’t Go Away: Why Counting Russia’s Costs Must Start With Human Capital and End With Schools

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

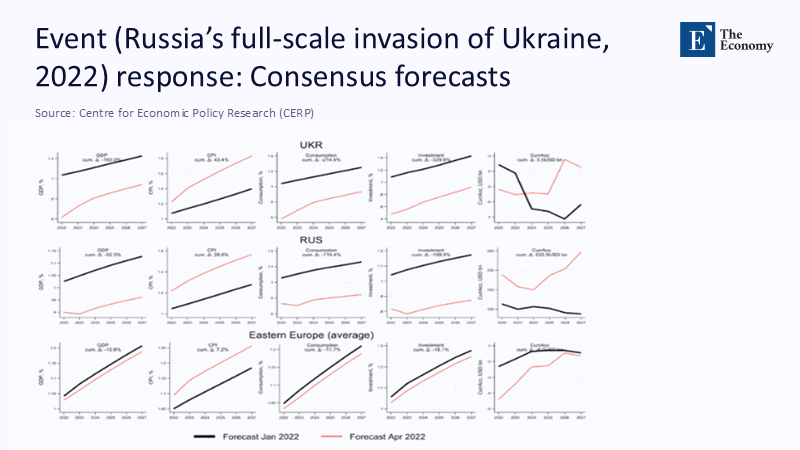

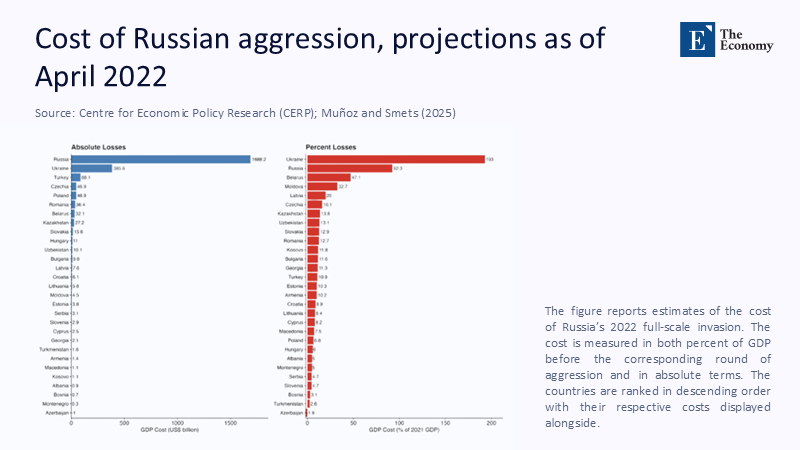

The most conservative cross‑country accounting now puts the total economic cost of Russia’s full‑scale invasion of Ukraine at about $2.4 trillion. That sum is roughly the size of Italy’s entire economy in 2025, and, depending on exchange rates and the dataset used, within striking distance of Russia’s annual GDP (≈$2.0–2.1 trillion). In other words, on present estimates, this war has already burned through the equivalent of a full year of Russian output, and the meter is still running. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s ten-year reconstruction and recovery needs are now assessed at $524 billion, nearly three times its expected 2024 output. If we stopped there, we would still be undercounting. The reason is simple: the headline figures miss persistent, compounding losses in human capital—teachers and students displaced, curricula interrupted, research stalled, higher‑education collaborations severed—that quietly depress growth long after the guns fall silent. Those are not footnotes to the war’s balance sheet; they are the line items that determine whether Europe’s schools, universities, and training systems can pay back tomorrow what geopolitics is borrowing today.

Reframing the Ledger: From “Total Cost” to a Human‑Capital Balance Sheet

Human capital, in the context of war, refers to the skills, knowledge, and experience of individuals, particularly those in the education sector, that are essential for economic productivity and growth. The emerging consensus is that the war’s economic toll is staggering. But too often we treat the tally as a one‑off: a pile of destroyed infrastructure, a lost year of output, a welfare loss monetized and parked in a spreadsheet. That framing encourages fatalism—“the bill is the bill”—and obscures the single margin policymakers can still influence at scale: human capital. What matters for a professional readership in education is not only what has already been destroyed or diverted, but also what can be rebuilt, accelerated, and insulated so that the long shadow of war does not become Europe’s new baseline. This column, therefore, shifts emphasis from physical capital and macro aggregates to schools, skills, science, and systems—the parts of the economy that compound over lifetimes. The claim is direct: the $2.4 trillion estimate is a floor, not a ceiling, because it omits many war‑specific losses now depressing present and future productivity, particularly through education budgets and talent flows. Moving the policy lens to human capital changes the priorities, the timing, and the instruments we should deploy—now.

What the $2.4 Trillion Leaves Out—and Why the True Total Is Higher

The $2.4 trillion figure results from aggregating damage to Ukraine’s capital stock, the valuation of lost life and health, lost output, and broader knock‑on effects. It captures the macro picture but understates Russia‑specific liabilities that continue to accumulate beyond that ledger.

Three facts illustrate the gap. First, about €300 billion in Russian central-bank reserves remains immobilized across the G7, with the EU already ring-fencing “windfall” profits on those assets for Ukraine. Those future flows—and any eventual principal transfers—represent costs to Russia that are not embedded in the $2.4 trillion total. Second, energy revenue compression from sanctions enforcement has materially reduced oil‑and‑gas takings: the IEA reports Russian fossil‑fuel export revenues fell year‑over‑year in mid‑2025, with crude and product export revenues at multi‑year lows at points earlier in the year, despite higher volumes. Third, large‑scale emigration and reputational damage—documented by independent analysts—translate into sustained productivity losses and smaller tax bases, compounding over time. None of these Russia-specific penalties sits at the center of the headline $2.4 trillion number, but all push the actual cost higher.

Counting the Opportunity Cost to Classrooms

War reallocates public money. In Europe, that reallocation has included extraordinary transfers for humanitarian support and system capacity to educate displaced Ukrainians. By the end of June 2025, Eurostat recorded roughly 4.3 million people under temporary protection in the EU. If we conservatively assume one-third are school-age, that implies approximately 1.4 million pupils to be accommodated in European primary and secondary systems. Using the OECD’s latest cross‑country spending guideposts—about USD 11,900 per secondary student and USD 10,700 per primary student—and converting at recent EUR–USD averages, per‑pupil public spending easily clusters near €8,000–€10,000 across much of the EU. That yields an annual education outlay on the order of €11–14 billion to educate displaced Ukrainian children—excluding mental-health supports, language services, transport, and facilities. Inside Ukraine, the education sector alone has suffered an estimated $13.4 billion in damage, with teaching and learning repeatedly disrupted. These are not “sunk” costs. They are investments we must make to avoid scarring effects that would otherwise depress lifetime earnings and regional growth. Our methodology is transparent: assume one-third of minors; apply OECD per-pupil averages; bound the estimate with the EU’s spending ratios; and separate war-zone damage from host-country integration costs.

Russia’s War Budget vs. Education: The Crowding‑Out Trap

On the other side of the front line, Russia’s public finances are being militarized at a pace without precedent in post‑Soviet history. Military expenditure reached an estimated $149 billion in 2024 (≈7.1% of GDP) and is projected to be around 7.2% of GDP in 2025, with defense taking roughly a third of planned federal outlays. The finance ministry has lifted its 2025 deficit target as energy revenues sag and funding needs rise. The opportunity cost is plain: as defense absorbs more of the budget, civilian line‑items—from health to education—are squeezed, even if headline nominal allocations are maintained amid high inflation. Persistent price‑cap enforcement and sanctions on the shadow fleet raise financing costs for energy exporters and reduce fiscal buffers, which further tighten the belt elsewhere. In a country where schooling outcomes and research productivity were already uneven before 2022, that pattern is a recipe for slower future growth. This situation, known as the 'crowding-out trap', is where the ostensibly distant “cost of war” lands most directly on schools, teachers, and students.

Who Pays—and For How Long? Lessons from Debt History

It is tempting to say that large economies can “grow out of war debts,” as the United States appeared to do after 1945. The history is subtler. America’s debt‑to‑GDP ratio fell from about 106% in 1946 to around 23% by 1974, but that decline owed as much to primary surpluses, financial repression, and unexpected inflation as to growth. Today’s Russia faces a harder slope: structurally lower potential growth, higher defense burdens, weaker demographic prospects, and international isolation that raises the cost of capital. Even if headline GDP has been propped up by war production, net productivity suffers as capital and talent are diverted into military uses.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s reconstruction bill—$524 billion over the next decade—will not be met by domestic revenues alone; it will require sustained external finance, including windfall profits from immobilized Russian reserves and multilateral project pipelines. The sober lesson from mid‑century finance is not that debt melts away but that states must choose what to protect while debts are amortized. If Europe protects one thing, it should be education.

The Missing Costs Russia Can’t Hide—and Why They Matter for Policy

Independent researchers have catalogued Russia-specific losses that go well beyond aggregate war-damage tallies: hundreds of billions in financial-sector harm, refinery outages that have periodically knocked out a sixth of domestic gasoline and diesel production, energy-export revenue shortfalls, and a sustained outward migration of skilled workers. They also note frozen foreign reserves and a reputational hit that will keep risk premia elevated. These elements were not the focus of the headline “total cost” estimates, which is one reason we argue the actual bill is higher. For education policy, the connection is direct. A state that spends more than 7% of GDP on the military and faces depressed energy rents has less fiscal space to invest in teachers, labs, and universities. Emigration drains STEM classrooms, graduate programs, and research teams. And the reputational damages dry up international collaborations. If you are an education minister planning medium‑term budgets, these are not abstractions; they are the parameters of what you can realistically promise students and faculty.

A Measured Estimate of Europe’s Ongoing Education Burden

Because the war will not end with a signature, neither will the burdens of schooling end with the news cycle. To make the data actionable, consider a two‑scenario envelope for host‑country education costs. Baseline scenario: 1.2–1.5 million school-age Ukrainian children remain in EU schools in 2025–2026 at €8,500 per pupil (primary/secondary weighted mean using OECD guidance), implying €10–13 billion annually in direct education costs. High‑need scenario: The exact headcount, but with a €1,500 uplift for language instruction, counseling, transport, and materials, leads to €12–15 billion per year. These are not “aid” costs; they are investments with positive expected returns via higher lifetime earnings and fiscal contributions. The method is explicit—combine Eurostat’s protection counts with OECD per‑pupil outlays and add an incremental services premium—so policymakers can contest any parameter and adjust the estimate. What matters is that the arithmetic scales quickly, and that the out‑year implications are significant enough to demand multi‑year budget planning.

Designing an Education‑Centered Reparations Regime

If we accept that human‑capital losses drive the most durable part of the war’s bill, then reparations policy should be education‑first. A practical architecture already exists. The EU has authorized the use of windfall profits on immobilized Russian reserves to support Ukraine; similar instruments could capitalize a ring‑fenced Education Recovery Facility with multi‑year disbursements to: rebuild and modernize Ukrainian schools; finance teacher training and safe‑school retrofits (shelters, digital delivery, resilient power); and sustain host‑country integration supports targeted at language learning and trauma‑informed instruction. The World Bank’s RDNA4 gives sectoral baselines, and national ministries can co‑finance via matching grants. Enforcement actions on price-cap violations and shadow-fleet operations could feed civil penalties into the same facility, converting sanctions implementation into long-horizon education finance. None of this precludes traditional capital projects. It simply places learning at the center of Europe’s repayment schedule for the future.

Anticipating the Objections—and Meeting Them With Evidence

One objection is that Russia has weathered sanctions and can “afford” the war. The data say resilience is conditional: revenues have seen-sawed with oil prices; enforcement has tightened; and budget deficits have widened, even as military outlays surge. Another objection is that Europe cannot afford to prioritize education while defense needs grow. Yet EU public education spending already stands near 4.6–4.7% of GDP; protecting that share while channeling windfall profits and targeted loans into Ukrainian education is a feasible budgetary choice—especially given the long‑run growth premium on human capital. A third objection is that schools should yield to immediate reconstruction priorities. But RDNA4 places education among the top‑damaged sectors, where investment both crowds in private activity and reduces emigration incentives by restoring local opportunity. The final objection—that wartime finance will “look after itself,” as in post‑1945 America—ignores the distinct historical mechanism: the U.S. reduced debt‑to‑GDP over decades through surpluses, inflation, and repression—not growth alone. We will not stumble into that outcome. We must plan for it.

Why This Matters Now for Educators and Administrators

For superintendents in Warsaw or Berlin, the war’s cost shows up as classroom density, specialist shortages, and student support needs that are hard to fund within one‑year appropriations. For rectors and research councils, it arrives as lost partnerships, budget caps, and a quiet exodus of senior faculty. For Ukrainian education leaders, it is the day‑to‑day reality of rebuilding schools while teaching through air‑raid alerts. The correct response is not rhetorical sympathy but a policy re‑ranking that puts education at the spine of Europe’s medium‑term security. That means multi-year baseline funding for refugee education in host countries; stable, predictable transfers to Ukraine’s education ministry; and an EU-G7 compact to channel windfall profits and sanctions penalties into education-specific windows with transparent governance. If the war’s €‑and‑$ headline invites despair, the human‑capital ledger offers the opposite: compounding returns to targeted investment that can, quite literally, outgrow the war.

The Bill We Can’t Ignore

We began with a stark equivalence: the war’s $2.4 trillion cost equals about one large European economy or one year of Russia’s GDP. That arithmetic is bracing but incomplete. The decisive margin—the part that determines whether Europe’s societies regain dynamism—lies in human capital, not just in bridges and power plants. Suppose policymakers continue to treat education as a discretionary add‑on to “real” reconstruction. In that case, the cost curve will bend the wrong way: fewer teachers, more learning loss, persistent emigration, and slower innovation. The remedy is clear and doable. Insulate education budgets at home; finance an education‑first share of Ukraine’s recovery through windfall profits and enforcement receipts; and align reconstruction with learning‑led growth. History’s most durable debt‑reduction happens when states protect the engines of future income. Europe must therefore resolve that the first euros committed—and the last euros cut—go to its students, teachers, and researchers. That is how we turn a ruinous balance sheet into a growth strategy worthy of the bill.

The original article was authored by Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Vittal Vasudevan. The English version, titled "The (projected) cost of Russian aggression," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Brookings Institution. (2025, June). What is the status of Russia’s frozen sovereign assets? Retrieved July 2025.

Council of the European Union. (2024, May 21). Extraordinary revenues generated by immobilised Russian assets: Council greenlights the use of windfall net profits… Retrieved July 2025.

Council of the European Union. (n.d.). Impact of sanctions on the Russian economy (infographic). Retrieved July 2025.

Eurostat. (2025, July 3). Public spending on education was 4.6% of the EU’s GDP in 2022 (news release). Retrieved July 2025.

Eurostat. (2025). Temporary protection for persons fleeing Ukraine (monthly data). Retrieved July 2025.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2025, June). Oil Market Report. Retrieved July 2025.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2025, July). Oil Market Report. Retrieved July 2025.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2025, April). World Economic Outlook DataMapper: GDP, current prices — Russian Federation. Retrieved July 2025.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2024). Did the U.S. really grow out of its World War II debt? (Working Paper). Retrieved July 2025.

Kyiv School of Economics (KSE Institute). (2024, July). Energy Sanctions Impact Summary. Retrieved July 2025.

OECD. (2023). Education at a Glance 2023: How much is spent per student? Retrieved July 2025.

OECD. (2024). Education at a Glance 2024 (overview and indicators). Retrieved July 2025.

Reuters. (2025, July 11). Russia’s fuel export revenue in June fell 14% from last year, IEA says. Retrieved July 2025.

Reuters. (2024, Sept. 30). Russia hikes 2025 defence spending by 25% to a new post‑Soviet high. Retrieved July 2025.

Russia Matters (Belfer Center). (2025, Feb. 24). Three Years Later: What Russia’s Aggression in Ukraine Has Cost It and What It’s Gained. Retrieved July 2025.

SIPRI. (2025, April). Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2024 (factsheet and press release). Retrieved July 2025.

StatisticsTimes. (2025, June 5). Projected world GDP ranking, 2025 (IMF). Retrieved July 2025.

U.S. Department of the Treasury (OFAC). (2023–2025). Price‑cap enforcement updates and FAQs. Retrieved July 2025.

UNDP / World Bank / European Commission / Government of Ukraine / UN. (2025, Feb. 25). Fourth Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment (RDNA4): $524 billion over ten years. Retrieved July 2025.

World Bank. (2025, Mar. 25). Learning and School Reforms Continue in Ukraine Despite War Challenges. Retrieved July 2025.

VoxEU (CEPR). (2025). Projected cost of Russian aggression. Retrieved July 2025.

Comment