A 10% Tariff That Behaved Like a Subsidy: Britain’s ‘Non‑Response’ Strategy and the Advantage It Quietly Built

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In late July 2025, the US and the European Union agreed on a deal that imposes a 15% baseline tariff on most EU goods entering the US. Britain, negotiating on a separate track, has been operating under a 10% baseline for most goods since April—lower still for some aerospace items and capped quotas in autos—while keeping services trade largely insulated. The five‑point wedge sounds trivial until you map it onto export composition and margins. The UK sells the United States far more services than goods by value; the EU sells the US far more goods than services. In other words, the tariff bites hardest where Europe is heavy and barely grazes where Britain is strongest. Business surveys confirm the intuition: most UK firms expect little or no change in sales, investment, or prices from the 2025 tariff announcements. A tax aimed at reordering global trade has, for now, reordered European competition—tilting it toward the UK rather than away from it.

Reframing the Debate: From “Tariff Shock” to “Relative Advantage”

The prevailing story treats 2025 as a protectionist rupture that spares no one—that frame mistakes level for differential. Policy outcomes have been governed less by the absolute size of the new US tariff wall than by its cross‑partner geometry. The EU accepted a 15% baseline to avert the threat of 30%. The UK, negotiating alone, has faced a 10% baseline since April, with sector carve‑outs that have narrowed exposure in aerospace and modulated the blow in autos via limited low‑rate quotas. Because the UK’s export basket to the US is dominated by services—where tariffs don’t bite—and high‑value niche manufacturing where origin rules can be met with last‑stage assembly, the effective shock to British firms is slight. That is not a claim of zero cost; it is a claim of relative insulation, which matters more for market share than the headline rate.

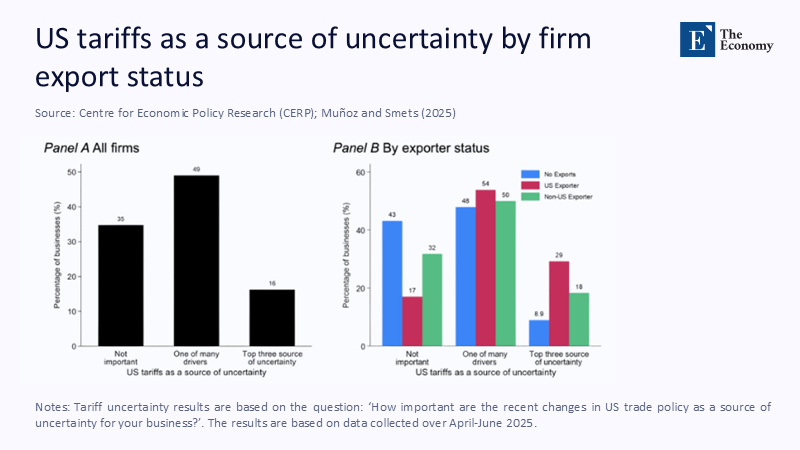

Seen this way, Britain’s policy approach looks deliberate in its restraint. The government did not trumpet grand gestures or retaliatory theatrics; it behaved, to all appearances, “as if the tariff were not imposed.” The virtue of that posture is practical: by refusing to manufacture drama, the UK preserved predictability for exporters at precisely the moment when continental rivals were absorbing a sharper shock. The Decision Maker Panel's evidence is telling. While tariff uncertainty rose, the share of UK managers expecting a material hit to core metrics remained limited—far lower than during Covid‑19 or the first Brexit adjustment. That differential in expectations is the policy instrument hiding in plain sight: decisions about hiring, pricing, and capacity are made on expected values, and on that front Britain’s baseline is calmer, cheaper, and, crucially, easier to model.

What the Numbers Say (and How We Estimate What They Don’t)

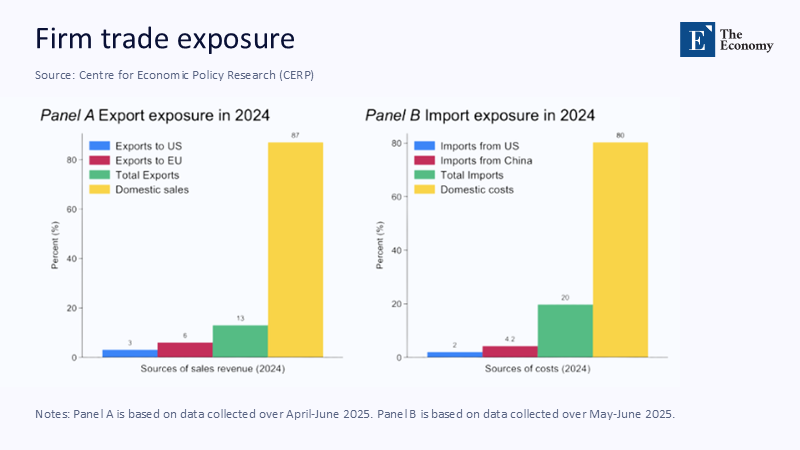

Start with the levels. Independent trackers place the United States’ average effective tariff near multi‑decade highs (≈17–18%), reflecting the new across‑the‑board increases and sector add‑ons in metals and autos. Within that elevated landscape, the spread between a 10% UK baseline and a 15% EU baseline is the lever that moves relative prices at the firm level. We translate that wedge into a simple, transparent estimate: multiply each economy’s share of goods exports sold to the US by its baseline rate to get an upper‑bound “revenue drag,” then adjust qualitatively for services insulation. For the UK, goods sent to the US account for roughly a sixth of total goods exports; for the EU, about a fifth. A 10% levy times 16–17% suggests a ≈1.6–1.7 percentage‑point gross drag on UK goods revenue; a 15% levy times 20–21% yields ≈3.0–3.2 points for EU exporters. Even before pass‑through and substitution, the asymmetry is apparent.

The methodology here is intentionally conservative. It assumes full pass‑through to prices, no margin compression, and no rerouting—biasing the result toward overstating the pain. Actual incidence will be lower for firms with pricing power and for those able to adjust rules-of-origin by shifting final assembly, especially in high-value, low-weight goods. Meanwhile, the services cushion is not modeled numerically but documented empirically: ONS data show a substantial and rising UK services surplus with the US, with services accounting for the majority of UK exports to America. That is the ballast that makes a 5‑point goods tariff wedge decisive for some European rivals yet manageable for Britain. Finally, we triangulate against manager expectations: the Decision Maker Panel’s mid‑2025 results report a majority of firms anticipating no material impact on prices and only minor adverse effects elsewhere—consistent with our back‑of‑the‑envelope arithmetic.

Sectoral Fault Lines: Autos Hurt, Aerospace Floats, Niche Manufacturing Adapts

Autos are the outlier by design. A 25% tariff on passenger vehicles and parts—layered on top of any baseline—compresses margins irrespective of the UK’s 10% corridor. British carmakers paused exports in the spring, and sector forecasts were cut. The subsequent UK–US arrangement that allows a limited number of vehicles to enter at the 10% rate softens, but does not eliminate, the pressure. This is where the “the tariff didn’t matter” trope fails: it matters in autos, acutely. Yet the sector’s weight in the UK’s overall US trade is smaller than in key EU economies, where car exports to America are central. As a consequence, the EU’s 15% baseline plus autos pain produces a more profound, broader shock than Britain’s autos‑specific hit.

Aerospace and selected high‑tech lines tell a different story. Multiple carve‑outs, including UK aerospace exceptions and exemptions covering parts within the civil aviation agreement, have reduced tariff exposure for critical supply chains. That is not a trivial footnote. Aerospace and adjacent engineering services are among the UK’s signature transatlantic strengths, with deep clusters in the Midlands and the South West. The presence of carve‑outs—and the credible expectation of further quota‑based relief in metals—has steadied order books and allowed firms to plan around friction rather than panic over it. In a world of tariff scatter, Britain’s product mix looks better hedged than Europe’s, and sector‑specific derogations magnify that hedge.

The Services Cushion and the Quiet Role of Export Finance

Tariffs hit goods; Britain sells services. In the four quarters to Q4 2024, the UK ran a sizeable services surplus with the US, and services comprised the majority of total UK exports to America. Consultancy, finance, legal, creative, engineering, and digital services are regulated through access and standards rather than border taxes. That means a five‑point goods wedge can reshape where factories sit at the margin, but the core of Britain’s transatlantic commerce rides on non‑tariff architecture: data adequacy, mutual recognition of professional qualifications, cloud rules, and capital‑market plumbing. This composition insulated British firms from the brunt of 2025’s tariff surge in a way continental exporters could not replicate.

Add a second buffer: UK Export Finance. UKEF’s 2024–25 support—roughly £14.5–£14.7 billion in new loans, insurance, and guarantees—reduced financing spreads for exporters precisely when working capital was most at risk. That counter‑cyclical backstop matters for SMEs attempting to pivot supply chains to meet rules‑of‑origin thresholds or to carry higher inventories against customs delays. It also signals policy credibility: when government finance stands behind export orders, managers are less likely to slash capex in response to headline shocks. In effect, the UK’s “non‑response” was not indifference; it was quiet institutional scaffolding—a combination of services, heft, and export finance that absorbed the blow.

From Shield to Magnet: Why Location Decisions May Tilt Back Toward the UK.

The claim that firms could return to London would have sounded fanciful a year ago. Today, it is a live contingency appearing across business media and market chatter. The logic is straightforward: for U.S.‑facing production where final assembly confers origin, a consistent five‑point tariff advantage over the EU changes the arithmetic, especially in high‑margin, low‑weight goods. If the UK can pair that wedge with robust services ecosystems—legal, financial, creative—that anchor headquarters and design, marginal location decisions flip. Early reporting and commentary have flagged precisely this possibility as the EU settled on a 15% baseline and the UK maintained the 10% corridor.

We should keep our heads. Autos will not flood back to Britain under a 25% sector tariff with limited quota relief, and the picture in metals remains politically managed. Yet the direction of travel is what matters for five‑year plans. Business services tied to US clients, medical devices that can meet origin with UK final assembly, creative and digital exports that hinge on data access—these are precisely the categories most likely to respond to a wedge that is predictable in policy and legible in compliance. And as the US flirts with even higher “world tariffs” of 15–20% for non‑deal partners, relative certainty inside the UK–US corridor becomes an asset in its own right. Firms don’t need perfect foresight; they need a modelable path. Britain currently offers one.

Implications for Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers

For educators and university leaders, the immediate task is to align talent with the geography of demand. As US‑facing roles grow in compliance, data, and standards, curricula should braid trade law, rules-of-origin documentation, analytics, and sector-specific regulation (FDA for med-tech, FAA/EASA interfaces for aerospace, SEC/FINRA for fintech). Placement offices should expand partnerships with exporters in pharmaceuticals, creative tech, and engineering services, where the UK already sells heavily to the US. The aim is not to chase headlines, but to rebuild the bridge between academic training and the new, tariff‑shaped contours of transatlantic trade. That bridge will determine whether the UK can convert a relative price edge into a durable capability edge.

For policymakers, the sequence is precise. First, lock in certainty: publish sector‑by‑sector rules‑of‑origin primers and commit to fast, predictable advance rulings so SMEs can structure supply chains without fear of retroactive reclassification. Second, modernize customs where it matters most—pre‑clearance for frequent shippers, simplified declarations for low‑value consignments, and interoperable data pipes with US customs to shrink dwell times. Third, double down on UKEF, with explicit SME coverage targets in tariff‑sensitive niches and co‑lending arrangements that stretch private balance sheets. Fourth, pursue services compacts with US regulators: mutual recognition for professional credentials, digital-trade corridors, and sandboxes that accelerate cross-border pilots in health-tech and fintech. In a high‑tariff world, the jurisdiction offering the smoothest non‑tariff interface to the US wins. Britain is nearest to that position among European economies; it should finish the job.

Anticipating the Pushback—and Answering It

“This is a blip; policy will reverse.” Maybe—but managers invest in expected values, not certainty. As of July 29, 2025 (Europe/Athens), the EU deal codifies a 15% baseline; the UK corridor remains at 10% for most goods; and credible trackers still place the United States’ effective tariff rate near historical highs. If volatility persists, the relative UK advantage persists with it. Firms can structure option‑like bets—modular plants, contracted final assembly, diversified logistics—to turn policy noise into manageable risk rather than existential hazard.

“A five‑point gap won’t move factories.” On its own, rarely. In stacked spreads—tariffs, exchange rates, compliance friction, finance costs—it often does. Pair the five‑point wedge with sterling’s tradable range and cheaper working capital under UKEF guarantees, and the math shifts. And location is not just factories. Headquarters, design, and services control towers are hypersensitive to regulatory friction. Those functions already cluster in the UK, making goods tariff‑eligible with final assembly, while running services and IP from London or the Midlands is exactly the hybrid model that spreads are meant to induce.

“Autos prove the U.K. is exposed.” Autos prove that sectoral add‑ons can overwhelm baselines, and they have. But composition matters. The UK’s transatlantic trade is services-heavy and diversified in high-value machinery and aerospace, with carve-outs; several EU economies are goods-heavy with significant exposure to US auto demand. The UK is not immune; it is less exposed where the pain is most important. That is the precise claim here.

“Europe will retaliate and erase the U.K.’s edge.” The EU’s leverage is real but constrained. The bloc just accepted a 15% baseline to avoid worse; escalation would raise costs on its exporters already hit by the goods‑heavy mix. The UK’s service‑dominant ties to the US, coupled with carve‑outs and finance scaffolding, mean the marginal cost of escalation is lower for Britain than for the EU—and the political appetite in London has favored calibration over confrontation. The smart policy is to entrench the 10% corridor with credible administration and to widen service bridges rather than play tariff tit‑for‑tat.

Hold the Nerve, Speed the Work

We began with a puzzle: the highest US tariff environment in generations, yet UK managers were largely unfazed. The puzzle dissolves when we look at relative exposure. By holding a 10% baseline while the EU accepted 15%, by leaning into a services‑led export profile, and by buttressing firms with UKEF support, Britain turned a global tariff surge into a relative advantage. That advantage will not persist by accident. It will continue if we convert a price spread into institutional capacity: frictionless rules‑of‑origin guidance, modernized customs, predictable finance for exporters, and services compacts that make regulatory access the actual moat. The UK did not “win” a trade war; it positioned itself to manage one better than its neighbors. That’s the doctrine worth adopting now: hold the nerve, speed the work, and treat the current wedge as a platform for durable capability rather than a windfall to be admired from afar.

The original article was authored by Nicholas Bloom, a William Eberle Professor of Economics at Stanford University, along with six co-authors. The English version, titled "The impact of the 2025 US tariff announcements on UK firms," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Al Jazeera. (2025, July 27). US and EU agree on 15 percent tariffs, averting transatlantic trade war. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

Bank of England. (2025, June). Decision Maker Panel – latest results, 2025 Q2. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

Budget Lab at Yale. (2025, July 28). State of US Tariffs: July 28, 2025. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

CEPR VoxEU. (2025, July 27). The impact of the 2025 US tariff announcements on UK firms. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

Holland & Knight. (2025, July). Reciprocal Tariff Update: State of Bilateral Negotiations. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

House of Commons Library. (2025, June). US trade tariffs – briefing (CBP‑10240). Retrieved July 29, 2025.

ONS (Office for National Statistics). (2025, July 25). UK trade in services: service type by partner country (dataset). Retrieved July 29, 2025.

UK Department for Business & Trade. (2025, June 19). United States – UK Trade and Investment Factsheet. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

UK Export Finance. (2025, July). Economic impacts of our support 2024–2025. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

UK Export Finance. (2025, July). Record £14.5 billion of export financing supports 70,000 jobs. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

The Guardian. (2025, July 27–29). EU–US trade deal: 15% baseline tariff and implications; live coverage and analysis. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

Reuters. (2025, July 28–29). US and EU avert trade war with 15% tariff deal; comparison of EU and UK trade deals. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

Comment