India to Conduct National Census Including Caste — A Historic Reckoning with Social Inequality

Input

Changed

India Launches Caste-Based Population Census A Measure to Enhance the Precision of Welfare Policies Educational Polarization Undermining Future Growth

For the first time since gaining independence in 1947, India is preparing to take a bold and controversial step: including caste data in its next national census. This move marks the first official effort to document the country's complex caste structure in more than 90 years, since the last such enumeration in 1931 under British colonial rule. While the government frames the initiative as a means of sharpening welfare policy and addressing inequality, it arrives amid a backdrop of stark economic divides, educational crises, and deeply rooted social hierarchies.

With more than 1.4 billion citizens, India’s developmental journey has been celebrated globally for its scale and speed—but also scrutinized for whom it leaves behind. From dilapidated village schools to Silicon Valley’s executive suites, the caste system’s lingering shadow continues to define lives in ways the state has long chosen not to officially acknowledge. Now, with a swelling population of young people and growing economic pressures, the government is signaling a willingness to confront these stratifications more directly.

Resurrecting a Silent Divide: The First Caste Survey Since 1931

On May 29, Nikkei Asia reported that the Indian government has approved a full-scale caste census to be included in the upcoming national population survey. Ashwini Vaishnaw, spokesperson for the government, announced that the Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs decided to incorporate caste categories into the census, calling it a reflection of “the government’s commitment to the values and interests of society as a whole.”

This marks the first time since 1931—during the colonial period—that caste data will be officially collected at the national level. After independence, Indian leaders deliberately avoided further caste enumeration, citing concerns over administrative feasibility and fears of provoking social unrest. A partial attempt was made in 2011, but the data was deemed unreliable and never made public. If completed, the upcoming survey would be the first comprehensive and credible snapshot of caste composition in postcolonial India.

Although the Indian constitution formally abolished the caste system in 1947, the social order it reinforced has endured with remarkable persistence. The caste structure, rooted in a 3,000-year-old tradition, divides Hindus into four principal groups: Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (nobles/warriors), Vaishyas (merchants), and Shudras (laborers). Beneath them lie the Dalits—historically referred to as “untouchables”—who remain socially and economically marginalized, and are still subject to violence, exclusion, and systemic neglect. In many parts of the country, acts of violence against Dalits are trivialized or go unpunished, underscoring the reality that constitutional equality has not yet translated into lived equality.

Despite India’s official stance on caste neutrality, the real world tells a different story—one in which caste affiliations continue to influence marriage, employment, education, and access to public services. Critics of the caste census, including members of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), warn that releasing caste-based data could fuel inter-group tensions and revive dormant hostilities. Yet proponents argue that transparency is essential if India is to craft policies that genuinely uplift its most disadvantaged citizens.

An Education Crisis Rooted in Inequality

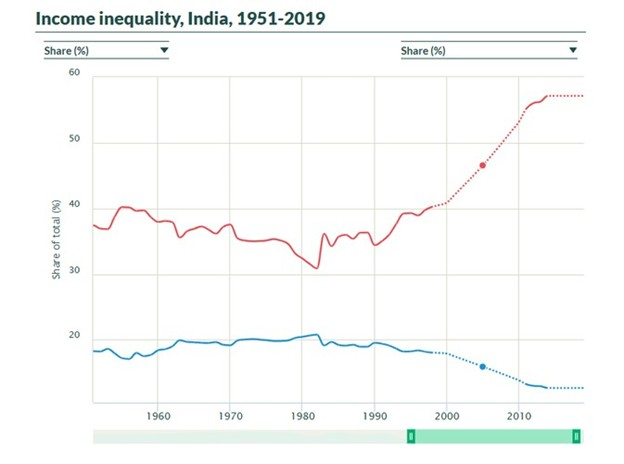

The push for a caste-based census is unfolding amid intensifying concern over India’s growing wealth and education gaps. While India’s economy has shown impressive growth, the benefits have not been equitably distributed. According to the World Bank, the top 10% of Indians now control 77% of national wealth. Without addressing this concentration of economic power, the Bank warns, India’s growth may falter under the weight of inequality.

At the heart of this imbalance is the crisis in education. As of 2023, India had over 265 million students enrolled across nearly 1.5 million schools. Yet quality of education remains highly uneven, especially between urban and rural regions, and between private and public schools. According to the 2022 Annual Status of Education Report (ASER)—which surveyed mostly rural children, who make up three-quarters of India’s youth—the foundational skills of millions are dangerously lacking. Only 26% of fifth-grade students could perform basic division, and less than 70% of eighth graders could read at a second-grade level.

Enrollment statistics tell a similar story. While 95% of children in states like Chhattisgarh are enrolled in primary school, high school enrollment plunges to just 57.6%. Over the past decade, the government has attempted to improve access to education through new school buildings and wider enrollment drives. However, learning outcomes remain stagnant. In fact, a 2017 surprise inspection found that one in four public school teachers were absent—symptomatic of a system where accountability and investment often fall short.

These inequalities are further exacerbated by a two-tiered education system that disproportionately favors the elite. After independence, India adopted a nation-building strategy focused on developing a select group of high-achieving individuals through prestigious universities and elite institutions. While this produced global success stories—such as Google CEO Sundar Pichai, a graduate of the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Delhi—it also led to massive underinvestment in basic education for the majority.

Today, competition for entrance into IITs is so intense that families often go into debt or sell property to finance costly tutoring. Meanwhile, students in underfunded public schools are left with overcrowded classrooms, outdated materials, and limited teacher engagement. Raj Kumar, a PhD student at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology, attributes this disparity to “the remnants of the caste system,” arguing that the educational divide is both a symptom and a cause of India’s broader socioeconomic inequality.

Balancing Data and Division: A Risky but Necessary Step

The idea of disclosing caste-based population data remains fraught with political and social risks. While India’s constitution bans caste-based discrimination, social practices have proven more resistant to change. Inter-caste marriages are still taboo in many regions, and the stigma attached to lower castes remains deeply embedded in cultural norms.

Opponents of the caste census warn that such a move could deepen social divides and provoke political manipulation. The BJP, India’s ruling party, has repeatedly voiced opposition to caste enumeration, concerned that it may undermine national unity and exacerbate identity politics. Yet others argue that refusing to collect caste data only perpetuates ignorance and masks inequality behind a veil of formal neutrality.

For many advocates, the caste census is not about stirring division, but about confronting uncomfortable truths. By understanding the real distribution of caste and class in society, India can craft more equitable policies—particularly in education, employment, and welfare. It is a recognition that one cannot address what one refuses to see.

India’s decision to undertake this historic survey is both courageous and contentious. It challenges decades of silence on one of the country's oldest injustices and signals a turning point in how the nation may approach inclusivity and justice. As India grapples with a new generation of challenges—economic transformation, youth employment, and educational reform—its future may well depend on how honestly it reckons with its past.