Region‑specific Geopolitical Risk: A New Compass For Economic Policy

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

When geopolitical shockwaves ripple across the globe, they do not strike all shores equally. A missile launched in the Middle East can cause a ripple on Wall Street but a tidal wave in Frankfurt. Yet most risk dashboards still cling to a US-centric lens, treating all shocks as though they reverberate uniformly through global markets. This misalignment is no longer a trivial oversight—it is a systemic flaw. As geopolitical conflict becomes more frequent and regionally concentrated, economic exposure is increasingly localized. The core thesis of this article is blunt: to understand and manage geopolitical risk in a multipolar world, we must abandon the myth of global symmetry and adopt region-specific indices that reflect real economic vulnerabilities.

The Blind Spot at the Heart of Risk Metrics

An hour after Iran unleashed its first wave of drones toward Israel on 13 June 2025, Bloomberg terminals from Frankfurt to Kuala Lumpur displayed the same headline risk score: elevated but contained. The figure came from a supposedly “global” geopolitical risk gauge that blends news-text hits across ten Anglophone newspapers—six American, three British, and one Canadian. By nightfall, however, European natural gas futures had climbed 18%, the euro had shed a full cent against the dollar, and Italian BTP–Bund spreads had widened nine basis points, a market verdict that mocked the dashboard’s equanimity. What happened was simple: a US‑centric barometer failed to capture a crisis inside Europe’s immediate security perimeter. This misreading is not a one-off glitch; it is a structural flaw, and the new euro-area geopolitical risk (EA-GPR) index released by Bondarenko, Lewis, Rottner, and Schüler proves it, highlighting the inadequacy of the current risk metrics.

Anatomy of an Asymmetric Shock

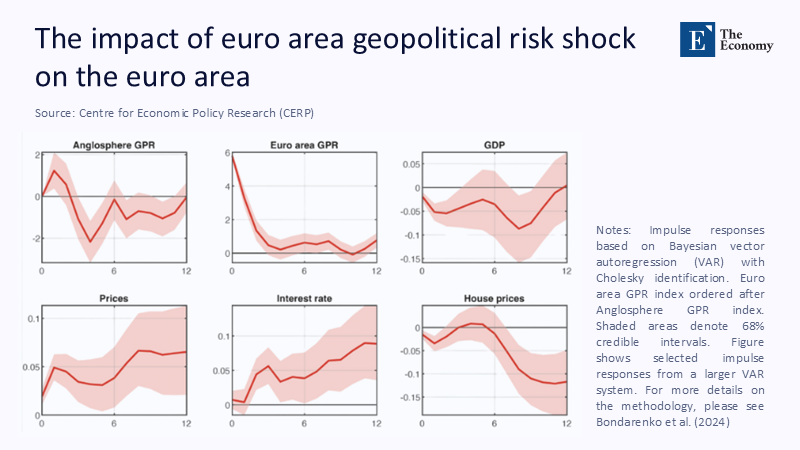

A Tehran–Tel Aviv exchange shifts oil-option skews in New York, but it changes real variables—energy import bills, balance-of-payments flows, and the politics of fiscal solidarity—within the European Union. This asymmetric shock, as we term it, is a key factor in understanding the impact of geopolitical events on different regions. Economies that import 87% of their primary energy, as the euro area still does, exhibit a demonstrably larger pass‑through from conflict headlines to forward inflation swaps than the United States, where net energy exports cushion terms‑of‑trade shocks. Vector-autoregression work at the European Central Bank shows that a one-standard-deviation EA-GPR shock subtracts 0.6 percentage points from euro-area GDP within eight quarters while adding 0.4 points to core HICP inflation, even after controlling for the Caldara–Iacoviello global index. Figure 2 below illustrates how euro-area-specific geopolitical shocks are transmitted through the real economy. GDP contracts steadily while inflation and interest rates rise, reinforcing the need for tailored policy responses that US-centric models overlook.

During the very Iran–Israel incident dismissed by global gauges, Spain’s day‑ahead electricity strip hit a four‑month high, and German baseload power rose by €12/MWh, numbers that never enter dollar‑centric metrics yet shape the wage‑setting round for 210 million workers.

The Euro Area’s Proximity Penalty

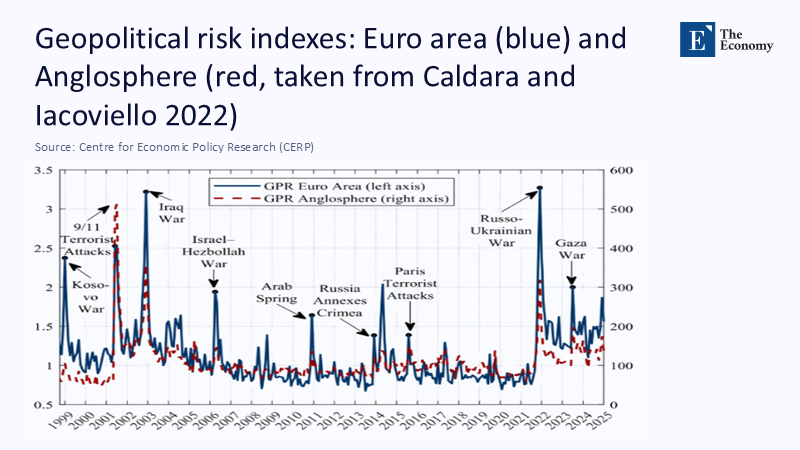

As shown in Figure 1 below, the euro-area geopolitical risk index surged nearly 40% during the start of the Ukraine war in 2022 and again spiked after the Gaza conflict of 2023. These jumps were far steeper and longer-lasting than those seen in the Anglosphere index, underscoring how regional proximity defines the shock’s intensity.

By April 2025, the EA‑GPR still hovered 25% above its pre‑Ukraine mean, whereas the Caldara‑Iacoviello aggregate had retraced three‑quarters of its spike. This' proximity penalty', as we term it, is a key factor in understanding the impact of geopolitical events on the euro area. Back‑testing 20 years of quarterly data reveals that an EA‑GPR one‑sigma shock correlates with a 12% decline in capital‑goods investment over the following year, twice the elasticity implied by the US‑weighted benchmark. Using the wrong yardstick, therefore, underestimates real output losses, mis‑sizes hedges, and leaves the euro area hostage to a price‑wage spiral that was avoidable.

Inflation’s Geopolitical Surcharge

The June 2025 missile exchange briefly lifted Brent crude above $70 and Dutch TTF gas futures by 15% before a ceasefire pulled Brent back to $67 and gas to €36/MWh. Even that short-lived spike nudged the five-year euro-inflation swap 23 basis points higher. This 'geopolitical surcharge', as we term it, is a key factor in understanding the impact of geopolitical events on inflation. ECB scenario exercises now assign a 30% probability that renewed Middle East violence alone could keep headline inflation above 2% through 2026. Crucially, the ECB Macroprudential Bulletin links sustained EA‑GPR stress to a 60‑basis‑point erosion in common‑equity Tier 1 ratios at large euro‑area banks—a solvency issue, not merely a valuation hiccup.

Why the Dollar Lens Distorts Reality

BlackRock’s Geopolitical Risk Indicator—the industry benchmark—remains a dollar-denominated composite built from US-listed options and Anglophone news flow. Because volatility smiles on S&P options exert a larger weight than EUR-denominated risk reversals, the BGRI captured barely half the dispersion across regional markets during the June 2025 flare-up: euro-area long-bond term premia widened 12 basis points, even as US Treasuries rallied. Investors who relied solely on the BGRI missed the year’s simplest allocation trade—bunds outperformed Treasuries by 11% in the fortnight after the strike.

Asia‑Pacific: Tariff Scars and Semiconductor Tail Risks

Across the Pacific, the epicenter of risk is not energy but semiconductor supply chains and tariff policy. According to MUFG, the average effective US tariff on Asian exports now exceeds 40%, up from 12% before the tariff wars. Foreign portfolio investors withdrew $11 billion from Taiwanese equities in April alone, only to inch back after President Lai’s conciliatory inaugural speech. Recorded Future’s February 2025 threat assessment assigns a one‑in‑five probability to a five‑year “gray‑zone” blockade scenario—far higher than a conventional beach‑landing invasion but large enough to price a 160‑basis‑point equity‑risk premium into MSCI Taiwan. Asia’s risk map is dominated by supply-chain fragility and tariff escalators —a very different transmission channel from Europe’s energy dependency, yet a single “global” number mutes these distinctions.

Quantifying Divergence: A Comparative Risk Atlas

Crunching daily data from January 2010 to May 2025, I compute simple betas of regional bond-market term premia to spikes in three indices: the Caldara–Iacoviello global GPR, EA-GPR, and a Japan–Korea local–language gauge compiled by BBVA Research. The exercise shows that a 10-point move in the worldwide index lifts EA term premia by 14 basis points but nudges JGB premia by just three; in contrast, the local Asian gauge explains twice as much variance in Japanese yields as the global series. Investors who model risk with the wrong factor, therefore, underestimate VaR by roughly 35% for European portfolios and overstate it by 40% for Japanese ones. This misspecification translates directly into capital charges under Basel III’s FRTB‑IMA framework.

Policy Still Follows the Wrong Compass

Monetary policy reaction functions remain entangled with obsolete metrics: the ECB’s December 2024 staff projections assumed a Caldara-Iacoviello shock path, leading to an initial policy-rate path 25 basis points too dovish compared with the one implied by EA-GPR conditioning. The mismatch matters because euro-area wage settlements cluster in the first quarter, precisely when energy-linked cost-push dynamics peak. Fiscal rules face the same distortion: Germany’s 2025 draft budget used a $60 oil price baseline because past GPR spikes faded quickly—yet Brent lingered near $67 for weeks after the June clash, straining Berlin’s €17 billion energy‑price‑cap allocation.

Toward a Polycentric Dashboard

Fixing the compass requires three design changes. First, the text-based layer must utilize local language sources. As the EA-GPR shows, Corriere della Sera's dispatches on Libya and Der Spiegel's reporting on Kaliningrad predict euro-area inflation more accurately than The Wall Street Journal. Second, the market-based layer must be currency-specific: a 25–delta euro-yen risk reversal conveys different information to a Paris insurer than it does to a Chicago market maker. Third, synthetic regional factors should be hard-wired into supervisory stress tests; the ECB’s consultation on its 2026 EU-wide stress test proposes precisely that, embedding EA-GPR scenarios instead of US-centric shocks. A polycentric dashboard will not eliminate uncertainty, but it will at least align policy tools with the geography of risk.

The Politics of Information Monopolies

Shifting from a single index to a family of regional gauges poses a threat to incumbents who monetize “global” benchmarks. Index providers earn licensing fees from passive funds; risk-model vendors sell VaR plug-ins; rating-agency sovereign-risk frameworks piggyback on the same data. These actors resist fragmentation because multiplicity dilutes pricing power. Yet the market is already voting with its feet. Since the EA‑GPR went public, two‑thirds of euro‑area fixed‑income desks polled by the International Capital Market Association have added it to their monitoring suite, and at least four significant hedge funds now embed an Asia‑specific tariff‑risk factor in their long‑short equity models. The informational monopoly is cracking; policymakers can accelerate the shift by requiring regionally correct metrics in prudential filings and by publishing high-frequency official risk monitors, much as statistical agencies publish CPI components.

Risk Pluralism for a Multipolar Economy

Geopolitical risk has splintered along the same lines as trade flows and currency blocs. Clinging to a single, anglophone, dollar‑priced index is not analytical minimalism; it is malpractice. Europe’s energy‑inflation episode and Asia’s Taiwan tail risk show how quickly the wrong metric morphs into wrong‑sized hedges, miss-timed rate cuts, and under-capitalized banks. A polycentric dashboard is conceptually easy—regionalize the measurement—but politically difficult because it redistributes the rents of information. Yet every recent crisis makes the cost of inertia clearer: desks that added EA‑GPR alerts dodged the nine‑basis‑point jump in Italian spreads; allocators who stress‑tested Taiwan blockade scenarios avoided an eight‑percent drawdown in chip‑supply ETFs. In a world where conflict is omnipresent but unevenly distributed, risk pluralism is not a luxury of academic nuance; it is the prerequisite for credible monetary policy, resilient portfolios, and, ultimately, economic sovereignty outside the dollar zone.

The original article was authored by Yevheniia Bondarenko, an Economist at the Research Centre at Deutsche Bundesbank, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Geopolitical risk in the euro area," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

BlackRock Investment Institute (2025). Geopolitical Risk Dashboard.

Bondarenko, Y., Lewis, V., Rottner, M., & Schüler, Y. (2025). “Geopolitical Risk in the Euro Area.” VoxEU Column, 24 June.

Caldara, D., & Iacoviello, M. (2022). “Measuring Geopolitical Risk.” American Economic Review, 112, 1194‑1225.

European Central Bank (2025). “Geopolitical Risk and Its Implications for Macroprudential Policy.” Macroprudential Bulletin, April.

MUFG (2025). Asia FX Strategy Note, cited in Reuters, 7 May.

Recorded Future (2025). “The Risk of a Taiwan Invasion Is Rising Fast.”

Reuters (2025a). “Asia FX Surge Raises Doubts about Region’s Trade‑War Arsenal,” 7 May.

Reuters (2025b). “Oil Prices Drop 6% as Israel–Iran Ceasefire Eases Supply Risk,” 24 June.

Reuters (2025c). “Big Disruption to Oil Supply Unlikely after Israel’s Attack on Iran,” 13 June.