When the Casting Vote Feels Foreign: Reframing Chinese-Diaspora Electoral Power Through the Eyes of Local Voters

Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

In 2025, Australians' trust in China to "act responsibly in the world" sat at 17%—yet Labor secured sweeping swings in Chinese-heritage electorates like Bennelong and Chisholm, where Chinese ancestry accounts for roughly 29–30% of residents and booth-level shifts reached double digits. In Canada, four in five citizens hold unfavorable views of China. Still, the federal inquiry into foreign interference confirmed that Chinese-language influence campaigns have targeted voters repeatedly since 2019, especially on platforms like WeChat. In the United States, 77% of Americans still view China unfavorably, even as Chinese American voters remain a small but growing component of winning statewide coalitions. For many "local" voters in these democracies—people who intend to raise families there and expect their institutions to be insulated from outside pressures—this contrast fuels a particular anxiety: if the balance of power tilts on issues refracted through Beijing, is electoral accountability drifting away from the priorities of those who will stay, pay, and parent under the policies enacted? That is the unresolved democratic tension our schools and universities must now help to manage.

Reframing the Debate: From "Minority Leverage" to "Local Legitimacy"

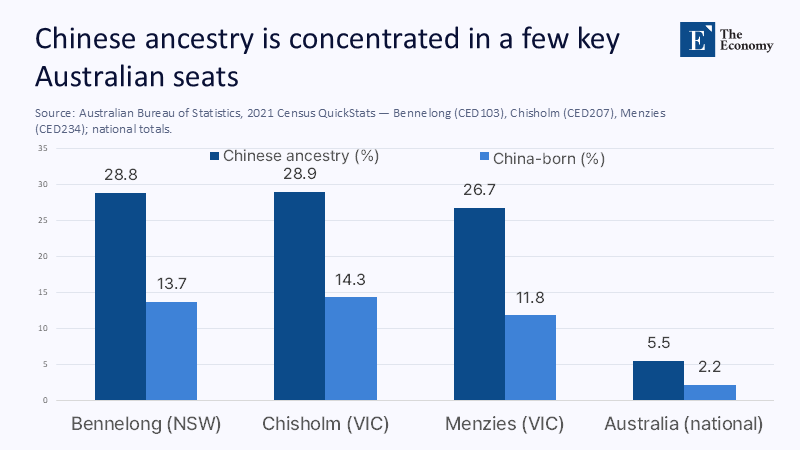

The loudest argument in public life today reduces Chinese-heritage voters to a "casting vote," moving governments toward a friendlier stance with Beijing. That framing is backwards. The real policy problem—especially for education systems that cultivate democratic norms—is how to preserve local legitimacy when a demographically concentrated diaspora intersects with a starkly negative public view of China. In Australia, Chinese ancestry is 5.5% nationally but clustered in marginal urban divisions; Bennelong's Chinese ancestry is about 28.8%, with 13.7% China-born. In Canada, the Chinese origin is 4.6% nationally, but exceeds 50% in places like Richmond, B.C. These concentrations magnify influence in close races not because diaspora voters are disloyal or monolithic, but because first-past-the-post or preferential systems translate local swings into outsized seat counts. The question locals are asking is not "why do they vote" but "does our system handle concentrated identity blocs without fracturing trust?" That is a design and education problem, not an anti-immigrant one.

What the Numbers Suggest (and How We Estimate Where They Don't)

Start with Australians' attitudes: the Lowy Institute's 2024 poll found only 17% trust China to act responsibly, and seven in ten see a future military threat. Meanwhile, Pew reports 2025 U.S. unfavorable views of China at 77%, softening only slightly from 2024. In Canada, Angus Reid shows 79% unfavorable toward China.

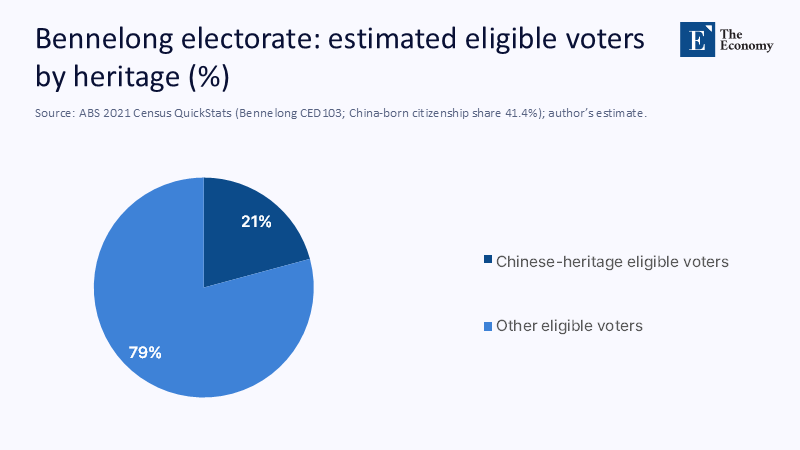

Now layer geography: in Bennelong, ancestry data (28.8% Chinese; 13.7% China-born) meets citizenship reality: among China-born people nationally, only 41.4% held Australian citizenship in 2021. To build a transparent estimate of eligible Chinese-heritage voters in Bennelong, we combine all Australian-born Chinese-ancestry residents (who are citizens) with the citizen share of China-born residents. If we conservatively assume ancestry≈electors, then eligible Chinese-heritage electors ≈ are 28.8% − 13.7% + (0.414 × 13.7%) ≈ ~20–21%. A 10-point swing within that group yields ~2 percentage points in the overall two-party margin—enough to flip tight seats.

The exact arithmetic explains Richmond Centre in Canada, where Chinese-origin majorities can decide outcomes even when national averages suggest otherwise. It's concentration, not conspiracy.

The Casting Vote and Conditional Belonging

Locals sense a paradox. On one hand, politicians moderate China's rhetoric to avoid backlash in Chinese-heritage seats, a pattern visible in Australia's 2025 race; on the other, foreign-influence headlines and intelligence findings keep the "China threat" salient. The political result is a cycle of conditional belonging: Chinese-origin communities are treated as kingmakers when parties need to win Bennelong or Chisholm, yet they are also cast under suspicion by stray "spy" insinuations that play into broader distrust. Notably, Australia's 2025 swings toward Labor in high-Chinese seats were amplified by backlash to remarks implying CCP infiltration of volunteers—remarks later condemned by party figures themselves as harmful. In Canada, the Foreign Interference Commission's final report catalogued repeated, targeted information operations in Chinese-language spaces in 2019 and 2021. The educational challenge is to separate legitimate national-security vigilance from racialized skepticism about civic participation. That separation is essential to keep local legitimacy intact when diasporic leverage is tangible, visible, and resented by many long-settled voters.

Transience, Permanence, and the "Rootedness" Anxiety

A distinct local worry is that diaspora leverage may be exercised by people who do not intend to remain. The evidence is mixed and often misunderstood. Many Chinese-heritage voters are Australian- or Canadian-born citizens whose local "rootedness" is not in question; others are naturalized after years of residence. Yet among China-born residents in Australia, only about 41% held citizenship in 2021—lower than some other migrant groups—reflecting a large pool of students and temporary residents who cannot vote but can shape community information ecosystems and volunteer in campaigns. The Canadian picture differs: roughly four in five eligible immigrants are naturalized, but recent analyses note relatively lower naturalization among China-born cohorts compared with others, complicating blanket claims of permanent settlement. For educators and administrators, the policy implication is precise: focus on the civic infrastructure around students, families, and community media rather than attempting to police motives. Schools and universities remain the republic's most diffuse civic institutions; they can harden democratic norms where residence is fluid and loyalties are debated.

Data-Led Implications for Educators and Policymakers

Three steps emerge from the numbers and the distrust. First, build language-layered transparency into election communication. Regulators and election commissions should require public ad repositories and disinformation takedown channels in both Chinese and English, matched to the platforms diasporic communities use, including WeChat. Canada's inquiry documented the scale and subtlety of such operations; Australia's debate over Chinese-language misinformation before the 2025 vote reveals the same need. Second, invest in civic-media literacy anchored in schools and universities, with assessment-aligned modules that explain preference flows, two-party-preferred counts, and how tiny margin changes in high-concentration electorates can determine national policy. Third, establish trust compacts: regular, recorded dialogues among school leaders, local election officials, and community media editors that clarify where advocacy ends and foreign interference begins. The aim is neither to sanitize diaspora politics nor to indulge local nativism, but to keep the public sphere legible when ethnic concentration meets global grievance.

Anticipating Critiques—and Meeting Them with Evidence

One critique says diaspora leverage is a democratic aberration requiring tougher citizenship or voting rules. The data argue otherwise. In Australia, the 2025 Bennelong result—Labor by ~9 points—was not conjured by non-citizens; it reflected lawful mobilization among eligible voters in a seat where ancestry and issues aligned. Another critique claims parties are "appeasing Beijing" to win Chinese votes. Yet polling shows locals remain deeply wary of China: only 17% of Australians express trust; 77% of Americans hold unfavorable views; 79% of Canadians hold unfavorable views. Parties emphasize cost-of-living, schools, and health in Chinese-heritage districts because those issues move votes across communities, while clumsy national-security rhetoric backfires. Finally, some argue that Chinese influence campaigns are exaggerated. Canada's formal inquiry, however, concluded that foreign state operations—including PRC-linked networks—did target elections in 2019 and 2021, primarily via Chinese-language channels. The correct response is targeted transparency and civic inoculation—not the collective suspicion that undermines local legitimacy and, in the classroom, corrodes trust in democratic institutions.

Universities and Schools as Democratic Stabilizers, Not Arenas of Proxy War

The education sector cannot fix geopolitics, but it can mitigate the democratic friction that concentrated diasporas produce. International students from China remain pivotal to campus life and budgets in Australia and the United States; their presence will continue to shape the information environment around elections. The task is not to securitize classrooms but to normalize civic engagement: encourage student associations, debate societies, and diaspora media clubs to co-produce fact-checking partnerships with public broadcasters in multiple languages; equip principals and deans with protocols that distinguish protected political speech from coordinated influence; and tie public funding to demonstrable civic-learning outcomes. Where governments contemplate restrictive measures—like visa revocations or politicized scrutiny of Chinese students—education leaders should present sober cost-benefit analyses: Chinese students still comprised a quarter or more of international enrollments in the U.S. in 2023–24, and Australia logged nearly 800,000 enrolments year-to-date April 2025. Policies that turn students into proxies will diminish both soft power and local trust without neutralizing hostile state operations.

The Local Mandate

Return to the uneasy truth: publics in Australia, Canada, and the United States remain overwhelmingly skeptical of China, while diasporic Chinese voters, concentrated in a handful of seats, can and do decide outcomes. That tension will not fade; demographic concentration and digital micro-targeting will keep it alive. Our answer should not be to question who belongs in the booth, but to strengthen the conditions under which locals—those who will live with the consequences—trust the process even when their bloc loses. That means language-layered election transparency, rigorous civic-media literacy embedded in curricula, and standing dialogues among educators, election officials, and diaspora media. If we build those civic settlements, the casting vote will feel less foreign, even when it is exercised by a community whose ties span the Pacific. The legitimacy that matters most in a democracy is not ethnocultural; it is procedural, educative, and earned anew, one election and one classroom at a time.

The original article was authored by Wanning Sun, a Professor of Media and Cultural Studies at the University of Technology Sydney. The English version, titled "How Chinese diaspora voters reshape Australian and US politics," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

ABC News (Australia). (2025). Bennelong (Key Seat) — Federal election 2025 results. Retrieved July 2025.

Angus Reid Institute. (2024). Favourability of nations: U.S. rebounds, India drops; views of China remain at historic nadir. (Poll summary and dataset).

Asian and Pacific Islander American Vote (APIAVote). (2024). 2024 AAPI voter survey — cross-tabs of registered voters.

AAPI Data. (2024). 2024 AAPI Voter Survey (overview & presentation).

ASPI – The Strategist. Fitriani, & Calwyn, N. (2025, Apr. 16). China targets Canada's election—and may be targeting Australia's.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2021). Chinese Australians — Census ancestry share.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2021). Bennelong, Census QuickStats (ancestry, birthplace, language).

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2021). Chisholm, Census QuickStats.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2024). Australia's population by country of birth (latest release; median ages; overseas-born share).

Department of Education (Australia). (2025). International student monthly summary and data tables (YTD April 2025).

Department of Home Affairs (Australia). (2021/2025). China-born community information summary; country profile — People's Republic of China; citizenship statistics 2023–24.

Foreign Interference Commission (Canada). (2025, Jan. 28). Final Report (Volumes & Executive summary).

Guardian (Australia). (2025, May 6). Huge swings to Labor from Chinese Australian voters in key seats… (news analysis & video package, May 22).

IIE — Open Doors. (2024). International students in the U.S.: Annual release & data portal. (2023–24 totals by place of origin).

Lowy Institute. (2024). Lowy Institute Poll 2024: Australians' attitudes to the world (17% trust China; high threat perceptions).

Pew Research Center. (2025). Negative views of China have softened slightly among Americans (77% unfavorable).

Pew Research Center. (2025). Global views of China and Xi in 2025 (25-country median favorability).

Statistics Canada. (2022). A portrait of citizenship in Canada from the 2021 Census (naturalization rates).

Statistics Canada. (2023). Census profile, 2021: Markham—Unionville; ethnic origin and language tables.

Tally Room (Ben Raue). (2022). What happened with the Chinese-Australian vote in the big cities? (booth swing analysis).

UTS: Australia–China Relations Institute (ACRI). (2025, May 5). Dutton wanted the Chinese-Australian vote… and the anti-China vote. It screwed his candidates.

Xiao, B., Fang, J., & Handley, E. (ABC News Australia). (2022–2025). Reporting on Chinese-Australian voters and key seats (various).

News.com.au (2025, May 9). How Chinese spy claims backfired; Guardian (2025, May 9). Gladys Liu demands apology from Jane Hume…; ABC live results tracker (2025)

Comment