The Long Shadow of Tariffs: Understanding the Long-Term Impacts for Informed Decision-Making

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

A single number should concentrate the mind: according to the WTO’s April 2025 outlook, world merchandise trade growth this year would have been roughly 2.7% under low-uncertainty, low-tariff conditions—but the combination of higher barriers and policy whiplash has carved that figure down materially, with the Secretariat explicitly attributing the gap to tariffs and uncertainty. At the same time, the United States has moved to impose sweeping new duties—between 15% and 41% on imports from more than 67 countries—with additional sector-specific levies on the way, including pharmaceuticals now and semiconductors soon. Meanwhile, China’s share of US goods imports has fallen to about 13–14%, while Mexico’s has risen to around 15–16%, a sharp re-plumbing of trade routes that masks rising costs within firms’ purchasing departments. Put these facts together and a truth emerges: the direct price effects of tariffs are only the opening act. The more consequential costs are indirect, delayed, and structural—borne through supplier risk premiums, compliance friction, and the quiet rewiring of global value chains. Those costs will not fully show up this quarter or even this year; they will compound across a presidential term and could reshape world trade for a decade.

From Visible Tariffs to Invisible Risk Premiums

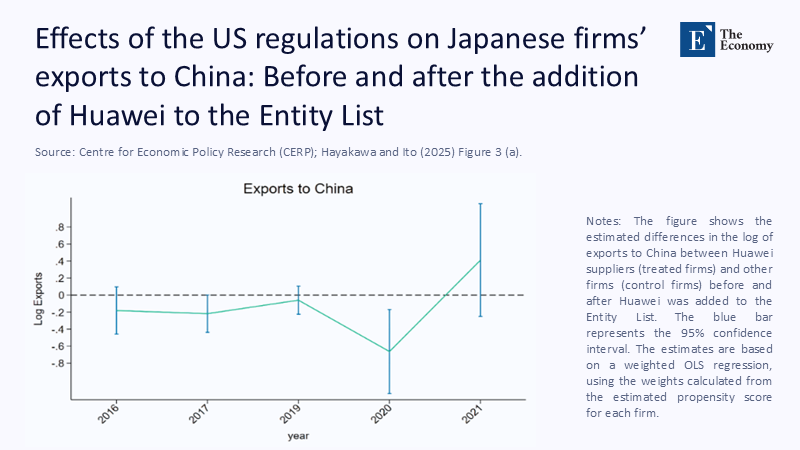

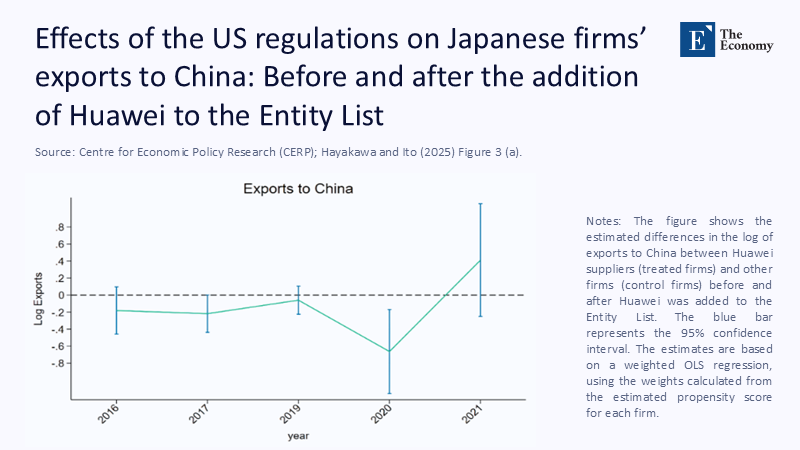

The textbook story stops at deadweight loss triangles, a concept that represents the inefficiency caused by taxes or tariffs, and higher sticker prices. The contemporary story starts there and then adds an invisible surcharge: a “risk premium” that firms assign to cross-border partners exposed to political or regulatory shocks. The new baseline U.S. tariff bands announced in late July 2025 are visible and immediate. Yet, the cost accountants inside multinationals are busier with something subtler—re-rating vendors by the fragility of market access, license requirements, and litigation risk. Export controls accelerate the same impulse. When Washington expanded foreign-direct-product rules to restrict advanced chips to Huawei, Japanese suppliers not directly exporting cutting-edge semiconductors nonetheless saw export declines, especially to unaffiliated Chinese buyers. The channel was not priced alone, but as a precaution. In parallel, policy uncertainty itself depresses trade and investment, as recent IMF and Federal Reserve work shows; volatility pushes firms to defer capex and shorten contracts, amplifying the indirect loss well beyond tariff revenue. This is the reframing that matters now: the meaningful welfare hit is not the tariff per se but the long tail of defensive behavior it triggers.

What the Numbers Already Reveal (and What They Miss)

The first wave of data shows the plumbing moving. Mexico overtook China as the top U.S. import source, accounting for roughly 15.5% of U.S. goods imports in 2024, while China’s share fell to 13.4%, according to analysis from the Dallas Fed. The WTO’s 2025 forecast flags how heightened tariffs and uncertainty have already clipped what would have been stronger trade growth; the gap between a 2.7% “low-friction” baseline and realized outcomes is, in effect, an early-warning readout of the indirect costs accumulating in supply chains. New U.S. executive orders layering 15%–41% tariffs across dozens of partners, alongside mooted sector levies, extend those headwinds, with details still shifting week by week—a further source of planning paralysis. Seen through the lens of the Japanese supplier case, the risk is compounded: export controls and tariffs radiate through networks, reducing sales even for firms two or three steps away from the sanctioned node. What the numbers miss—so far—is the option value of waiting now embedded in procurement: contracts shortened, second-source qualification extended, and inventory buffers raised. Those choices are real costs; they don’t show up neatly in monthly trade prints.

A Back-of-the-Envelope: Estimating Indirect Deadweight Loss

Because official statistics lag and firm-level data are proprietary, we can make a transparent estimate. Start with three defensible inputs drawn from current evidence. First, surveys of supply-chain leaders in 2024–2025 report widespread supplier diversification and elevated disruption risk, implying higher baseline operating costs even before new tariffs; one industry survey finds that over 60% of organizations reported high supply-chain risk in 2024. Second, academic and central-bank work links uncertainty to lower trade volumes and delayed investment, suggesting a measurable “uncertainty wedge.” Third, firm-level studies of tariff pass-through since the last trade war indicate incomplete adjustment in exporter prices and meaningful consumer incidence, especially for higher-priced firms.

Now the arithmetic: assume 20% of U.S. import lines undergo vendor switches or add a second source over 2025–2027. Conservatively assign an 8% landed-cost differential (qualification, smaller scale, logistics). If pass-through on these indirect costs is 60%, the aggregate price impact across the total import basket is roughly 0.96% (0.20 × 0.08 × 0.60). Even if downstream competition compresses margins so that only half of this reaches final demand, the residual 0.5% inflationary pressure annually for two to three years is material—especially layered atop explicit tariff effects. The deadweight loss is not just triangles; it is time, uncertainty, and duplication.

Propagation Mechanisms: How Today’s Rules Reshape 2030

Policy shocks travel through three main channels. First is network rerouting. Evidence from the last U.S.–China tariff cycle shows significant trade deflection—goods re-labeled via third countries or suppliers shifted to “China+1” hubs. Fresh research documents rerouting patterns and the compliance drag they impose, which refers to the additional administrative burden and costs incurred by businesses to comply with new regulations. Second is regulatory entanglement. Export-control updates since late 2024 extended long-arm jurisdiction over technology flows, with Japan and the Netherlands aligning in critical tooling segments and further talks continuing in 2025. This widens the circle of firms that must treat China-adjacent demand as contingent, not guaranteed. Third is macro feedback. The BIS’s 2025 annual review warns that fragmentation and trade disruptions elevate tail risks for growth and financial stability—conditions under which firms systematically under-invest relative to fundamentals. Put concretely: phase-two measures do not just change invoice totals; they alter who vendors with whom, where plants get built, and how CFOs price political risk into every cross-border commitment. That is why the tariff “effect” will not be visible in full within months. It will surface in the 2027 capex maps and the 2030 productivity tables.

Sectoral Fault Lines and the Education Angle

Where do these indirect costs bite first? In sectors with high certification thresholds and long supplier-qualification cycles—chips, advanced machinery, medical devices, and pharmaceuticals—the United States is signaling new levies and tighter controls. The week’s announcements about pharmaceutical tariffs, with semiconductor measures queued up, do more than raise import prices; they complicate compliance for downstream users in research labs and hospitals that rely on globally sourced inputs. For educators and administrators, this is not abstract. Universities and school systems will face procurement friction for lab equipment, networking hardware, and ed-tech devices whose component chains cross new tariff lines or export-control boundaries. OECD and UNCTAD analyses argue that resilience comes from diversified, agile networks rather than simple reshoring; curriculum and workforce training should mirror that reality by emphasizing supplier risk analytics, trade law literacy, and multi-region sourcing strategy. The classroom implication is clear: teach students to model second-order effects and to read rules as moving parts, not footnotes.

Policy Implications: Design for System Performance, Not Single-Point Wins

For policymakers, the core design principle is not self-sufficiency at any cost but system performance under stress. OECD guidance stresses that resilience depends on agility and alignment, not on shrinking exposure wholesale. Trade instruments should therefore differentiate between strategic chokepoints (where redundancy is worth paying for) and commoditized inputs (where blunt tariffs tax consumers without increasing security). The latest U.S. tariff orders are broad; the risk is that they incentivize indiscriminate vendor flight rather than targeted risk reduction. Education policy can help by funding translational programs—joint business-engineering modules on export-control compliance, public-procurement pilots that preference multi-sourcing over single-supplier “reshoring,” and shared data platforms that map supplier dependencies for schools and hospitals. The WTO’s forecast gap is a reminder that uncertainty is itself a policy variable; credible timelines, transparent carve-outs, and coordinated licensing standards can narrow that wedge more effectively than toggling headline tariff rates.

Anticipating the Counterarguments—and Rebutting Them

Three critiques recur. First: tariffs are a short, sharp shock that will fade as firms adapt. But the Japanese-supplier case shows that adaptation often means exit from risky segments, not frictionless substitution; losses persist in unrelated markets as firms avoid unaffiliated buyers perceived as vulnerable. Second: higher duties will quickly rebalance external accounts. Daniel Gros cautions that while bilateral balances will reshuffle, the current-account arithmetic is stubborn; savings-investment dynamics dominate, meaning the macro deficit moves little even as trade maps contort. Third: uncertainty is overblown. Yet central banks and the IMF work points the other way: measured uncertainty depresses trade and investment, with identifiable transmission channels and quantifiable output costs. Add in the policy reality that tariff details remain fluid days before implementation—15%–41% bands, partner-specific deals, sector carve-outs—and it is hard to argue that firms can plan with confidence. The near-term price tag is the least interesting part; the long-term, system-wide rewiring is.

The Aftershock Timeline

Return to the opening observation: absent rising barriers and uncertainty, 2025 global trade growth would be meaningfully stronger. Instead, we are stacking visible tariffs atop invisible risk premiums, export-control spillovers, and chronic ambiguity about the rules of the game. The policy results won’t crystallize in a single quarter’s CPI or a headline trade balance. They will propagate through supplier qualifications that take eighteen months, through capex cycles that take three years, through curriculum and procurement choices across campuses and hospitals that persist for a decade. The lesson for educators, administrators, and policymakers is the same: measure success not by the speed of a tariff announcement but by the resilience of the system it leaves behind. Set timelines, publish carve-outs, prioritize redundancy where it matters, and teach the next cohort to model second-order effects as rigorously as first-order price changes. Do that now, and we can shorten the aftershock. Wait, and the indirect losses will do the compounding for us.

The original article was authored by Kazunobu Hayakawa and Keiko Ito. The English version of the article, titled "The ripple beyond borders: Indirect effects of US export controls on Japanese firms," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Allen, G. C. (2024, December 11). Understanding the Biden Administration’s updated export controls. CSIS.

Bank for International Settlements. (2025, June 29). Sustaining stability amid uncertainty and fragmentation (Annual Report, Chapter I). BIS.

Bureau of Industry and Security. (2024–2025). News and updates. U.S. Department of Commerce.

Dallas Federal Reserve. (2025). China remains a modest player in U.S.–Mexico trade; Mexico’s import share reached 15.5% in 2024.

Goldman Sachs Research. (2025, April 6). The impact of uncertainty on investment, hiring, and consumer spending.

Gros, D. (2025, May 14). The indirect impact of Trump’s tariff war. Project Syndicate.

Haberkorn, F., & Hillberry, R. (2024, April 12). Global trade patterns in the wake of the 2018–2019 U.S.–China tariff hikes. Federal Reserve Board FEDS Notes.

Hayakawa, K., & Ito, K. (2025, August 1). The ripple beyond borders: Indirect effects of U.S. export controls on Japanese firms. VoxEU/CEPR.

Iyoha, E., & Pierce, J. (2025). Exports in disguise? Trade rerouting during the U.S.–China trade war (HBS Working Paper 24-072).

International Monetary Fund. (2024). The heterogeneous effects of uncertainty on trade (IMF Working Paper 2024/139).

J.P. Morgan Global Research. (2025). U.S. tariffs: What’s the impact? (Effective tariff estimates).

OECD. (2024, November). Promoting resilience and preparedness in supply chains. OECD Working Paper.

OECD. (2025, June 2). Supply Chain Resilience Review. OECD.

Politico. (2025, July 31). Trump issues order imposing new global tariff rates.

RapidRatings. (2025, May 29). The 2025 Risk Survey Report.

Reuters. (2025, August 5). U.S. to initially impose “small tariff” on pharma imports, Trump says.

UNCTAD. (2024, December 2). Global Trade Update (December 2024).

UNCTAD. (2025, March 14). Global trade 2025: Resilience under pressure.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2025). Top trading partners (June 2025).

WTO. (2025, April 14). Global Trade Outlook and Statistics 2025. World Trade Organization.

Financial Times. (2024, October 10). U.S. and Japan near deal to curb chip technology exports to China.

Comment