A New Cartography of Resistance: Sri Lanka’s Trilateral Pivot and the Quiet Rebellion against China’s Maritime Primacy

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

Its turquoise lanes appeared immune to the high-voltage rivalry that crackles above the Taiwan Strait or in the South China Sea for decades. Yet by 2025, the placid surface has begun to shimmer with unexpected defiance. A growing roster of littoral states—Sri Lanka foremost among them—has discovered that defaulting to Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is not destiny. Instead, they are redrawing their map of power, swapping single-source dependence for a multipolar portfolio that binds Indian stewardship to Gulf capital and, where applicable, to a sprinkling of Western support. Sri Lanka’s 5 April 2025 decision to develop Trincomalee and Colombo ports through a tripartite accord with India and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is more than a business deal; it is a manifesto in steel and concrete, a declaration that the water mass stretching from the Strait of Malacca to the Cape of Good Hope will no longer be an unchallenged extension of China’s strategic coastline. In that sense, the Indian Ocean is becoming for Beijing what mainland Southeast Asia already is for Washington and China combined: a proving ground for influence in which local agency, not superpower diktat, increasingly sets the tempo.

Sri Lanka’s Debt-Trap Reckoning

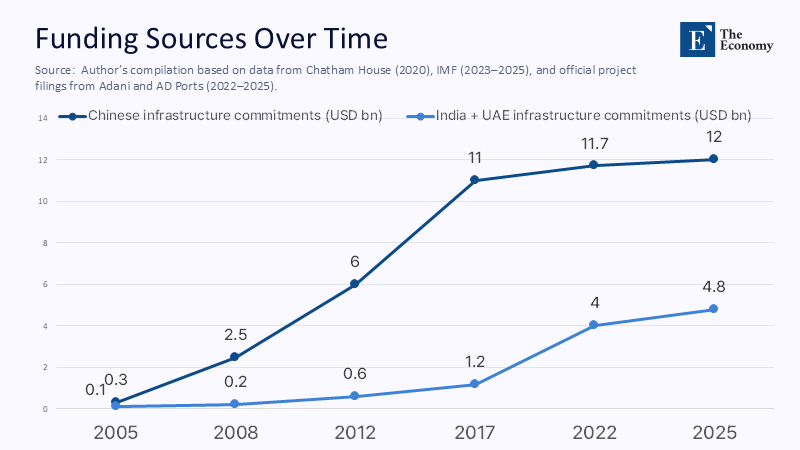

The pivot did not erupt overnight. It germinated in the slow, grinding realization that an island can drown in liquidity as surely as it can in salt water. Between 2005 and 2020, Colombo amassed roughly US $12 billion in Chinese infrastructure loans—ports, highways, power plants—each project wrapped in the promise of an export-led renaissance. The most infamous symbol was Hambantota Port, handed to a Chinese state-owned firm on a 99-year lease in 2017 after revenues fell short of even basic operating costs. Local newspapers likened the lease to “refinancing with a ball and chain.”

By 2022, when global energy prices spiked and tourism collapsed, Sri Lanka became the first Asia-Pacific country in two decades to suspend external debt payments. Foreign reserves plunged beneath US $50 million—barely enough to cover a week of fuel. The despair was visible: mile-long queues for petrol, day-long blackouts, and an urban middle class that watched savings evaporate in triple-digit inflation. Yet, in the face of these challenges, Sri Lanka remained resilient, a nation once marketed as the “resplendent isle” resembled, for a season, a cautionary footnote in an IMF white paper.

What matters for today’s analysis is how this nadir sharpened Colombo’s instinct for self-preservation. China postponed debt-restructuring talks, citing “internal procedures,” while India air-freighted rice, diesel, and essential medicines worth more than US $4 billion within six months. Widespread anger pivoted nearly as quickly as currency charts: street graffiti that once praised “Chinese friendship” began accusing Beijing of “sovereign foreclosure.” The political class took note. By the time the IMF approved a four-year, US $3 billion Extended Fund Facility in March 2023—followed by a fourth-review staff agreement in April 2025—Sri Lanka’s Cabinet had embraced a new mantra: diversification or demise.

The Mechanics of the Trilateral Shift

The Trincomalee Energy Hub and the Colombo West Container Terminal (CWCT) are the cornerstones of the India–UAE–Sri Lanka triangle. CWCT alone attracts about US $800 million, with Adani Ports leading the engineering efforts and Abu Dhabi Ports providing financial and technological expertise. The Trincomalee project, on the other hand, transforms a picturesque natural harbor into an energy-logistics complex that connects South Asian refineries to African crude and Middle-Eastern gas. Importantly, the equity structure is more balanced than in the Hambantota era: Sri Lanka Ports Authority holds a blocking stake, India’s Adani Group limits its share below majority, and the UAE’s portion is contractually protected from sovereign collateral clauses. Even Western lenders, who were previously wary of BRI's lack of transparency, see the appeal in this trilateral governance.

However, financial architecture is only part of the story; the other part is narrative control. Colombo now presents its ports not as “BRI pearls” but as “Indian Ocean service hubs,” a linguistic shift that removes Chinese symbolism from the physical infrastructure. The government now publishes concession contracts online, invites parliamentary oversight, and mandates that environmental impact assessments be reviewed by both domestic and foreign universities. Transparency, once seen as bureaucratic theater, has become Colombo’s strategic shield, protecting it from accusations of secret deals. In diplomatic circles, Sri Lanka promotes its model as “risk-shared growth”: India ensures sea-lane resilience, the UAE expands its logistics footprint, and Sri Lanka restores fiscal health without compromising its sovereignty.

China’s Evolving Toolkit: Builders Become Gatekeepers

Beijing has not retreated; it has regrouped. Gone are the days when Chinese diplomats could parachute into Colombo with a memoranda template and a briefcase of concessional loans. Today, Chinese influence is subtler—anchored in joint ventures for data cables, leases on bonded warehouses, and soft-power outposts like language institutes. Hambantota still hosts People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) research vessels under the guise of “hydrographic surveys,” allowing China to map the seafloor while testing regional red lines. Yet Beijing’s primary strategy is now integration rather than construction. By embedding itself in telecom backbones and cloud-computing facilities, China gains leverage that does not mature like a loan or expire like a lease.

This re-tooling is most evident in the “Chinese Overseas Logistics Network,” a patchwork of shipping platforms that funnels cargo from Pakistan’s Gwadar to Djibouti’s Doraleh. Sri Lanka remains the central node, but its government is pushing back on security clauses that once granted Chinese crews near-exclusive control zones. The Observer Research Foundation notes a qualitative shift: Beijing’s leverage is evolving “from loans that can be renegotiated to operating systems that cannot be unplugged without severe economic shock.”

How has China responded to the trilateral insurgency? With studied restraint. Instead of public condemnation, Beijing has rolled out charm offensives: scholarship quotas for Sri Lankan students, panda-themed cultural festivals, and an uptick in yuan-denominated trade lines for apparel exporters. The calculus seems clear: recast itself as an indispensable partner in people-to-people exchange while quietly lobbying to keep access rights at Hambantota. Whether that finesse will succeed is open to debate, but its mere existence underscores the narrative: Sri Lanka has forced China onto the defensive.

India’s Long Game Comes into Focus

If China built fast, India built trust. New Delhi’s relief package during the 2022 meltdown wasn’t pure altruism, yet its impact on public sentiment was unmistakable. Polling by Colombo’s Social Scientists’ Association shows favorable views of India climbing from 23% in 2019 to 62% in late 2024, while favorable perceptions of China fell below 40% for the first time in a decade. Trust has translated into complex contracts. Adani Ports now operates not only CWCT but also stakes in solar parks and power transmission lines linking northern Sri Lanka to Tamil Nadu’s grid, fostering energy interdependence that is politically palatable on both sides of the Palk Strait.

India’s calculus, however, extends beyond commerce. Securing Colombo as a cooperative maritime node dilutes the so-called Chinese “String of Pearls” strategy, which New Delhi’s naval planners view as a concentric chokehold around the subcontinent. As importantly, India’s partnership with the UAE opens doors to Gulf sovereign-wealth funds whose balance sheets dwarf those of Indian banks. By acting as a strategic manager rather than sole financier, India outsources part of the capital burden while retaining operational influence—a textbook study in asymmetric leverage. The result is a new maritime grammar in which Indian oversight, Emirati money, and Sri Lankan law co-author port governance.

Gulf Capital’s Quiet Ascendancy

The UAE’s silhouette on the Indian Ocean horizon has increased strikingly. Abu Dhabi Ports manages terminals from Sudan’s Port Sudan to Pakistan’s Karachi, adding Colombo to a near-continuous chain of logistics outposts. Yet Gulf engagement differs from China’s in two vital ways. First, it is explicitly commercial, seldom wrapped in civilizational rhetoric. Second, it avoids sovereign-guarantee loans, relying instead on equity and revenue-share models that distribute risk. This modality speaks to cash-strapped Indian Ocean governments seeking capital influx without new debt overhangs.

For the UAE, the incentive landscape is equally compelling. Diversification away from hydrocarbons demands a global logistics scale, and the Indian Ocean—home to two-thirds of seaborne oil trade—offers both traffic and brand visibility. Political neutrality is a strategic asset: Emirati envoys can dine with Chinese executives in the morning and announce India-backed terminal expansions by afternoon without being accused of ideological betrayal. Over time, this “quiet diplomacy of cranes and containers” may give the Gulf states soft-balancing power, cushioning smaller nations against the binary choices that define East Asian security debates.

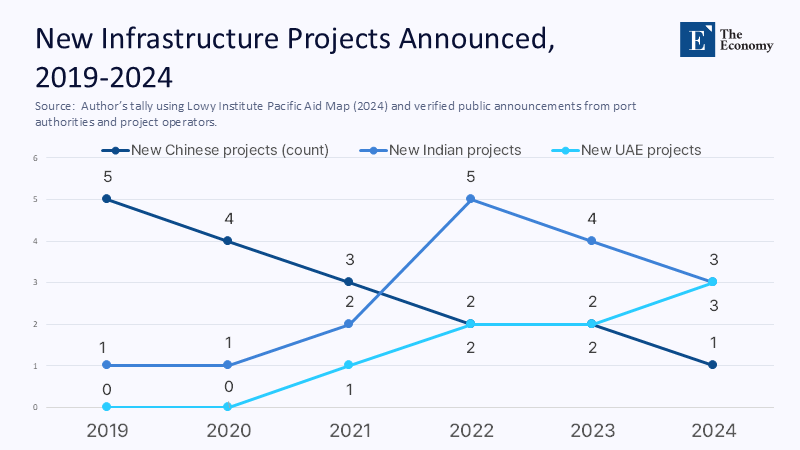

Ripples across the Wider Ocean

Sri Lanka’s rebellion is contagious. The Maldives, once the poster child for BRI excess, is renegotiating airport and housing debts even as it probes Japanese and Indian alternatives for a long-delayed transshipment port. Mauritius has signed a logistics facilitation pact with India, and Kenya is exploring a tripartite financing model for Lamu Port that would blend Saudi capital with Japanese dredging expertise. Lowy Institute tracking shows new Chinese infrastructure commitments across Indian Ocean islands fell by 38% between 2021 and 2023, a slide that began before pandemic-era slowdowns. Meanwhile, Indian development loans—although still modest—rose 19% in the same window.

This recalibration does not herald a wholesale exit of Chinese capital. Beijing remains the largest single investor in the Global South, and many governments still view Chinese contractors as unmatched in scale and speed. What is shifting is the diplomatic price of exclusivity. Countries that once feared antagonizing China now calculate that diversified financing shields them from coercive clauses and elevates their bargaining power with all suitors, including Washington’s new International Development Finance Corporation and Japan’s expanded Partnership for Quality Infrastructure.

Beyond Dependency: Writing a New Maritime Script

Sri Lanka’s trilateral turn is best read as a harbinger rather than an exception—a lighthouse that reveals submerged currents across the Indian Ocean. By yoking its recovery to Indian stewardship and Gulf liquidity, Colombo has demonstrated that sovereignty can be repackaged as a multilateral asset rather than a unilateral concession. The implications glide far beyond port throughput statistics. Maritime Asia may be edging toward a doctrine in which smaller states wield geography as negotiable equity, leveraging competing great-power anxieties to craft bespoke, interest-based alignments.

For Beijing, the lesson is sobering: transactional speed cannot substitute for reputational depth. For India, the takeaway is equally profound: strategic patience fused with crisis-time empathy can rewrite regional equations faster than any aircraft carrier deployment. And for the UAE—and perhaps the broader Gulf—the message is that financial diplomacy when executed with neutrality and efficiency, can translate into outsized geopolitical returns.

Whether this nascent order endures will depend on execution. Tripartite frameworks thrive on transparency but can unravel in bureaucratic lethargy; they promise shared equity, but risk diffused accountability. Yet if Sri Lanka manages to revitalize growth, meet IMF benchmarks, and keep both Hambantota lights on and Colombo cranes moving under a non-Chinese flag, it will have authored a new chapter in maritime statecraft—one where the Indian Ocean is not a chessboard for outside powers but a cooperative venture directed by its coastal custodians. In that future, the ocean’s map will be redrawn not in Beijing’s image but by a mosaic of regional choices that prove, finally, that dependency is a political option, not an iron law of geography.

The original article was authored by Manish Vaid, a Junior Fellow with the Observer Research Foundation. The English version, titled "Redrawing the map of power in the Indian Ocean," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Adani Ports & Special Economic Zone Ltd. (2025). “Operations Commence at Colombo West International Terminal.” Economic Times.

International Monetary Fund (2025). “Staff-Level Agreement on Fourth Review under Sri Lanka’s EFF.” IMF Press Release 25/122.

Lowy Institute (2024). “2024 Key Findings Report: Pacific Aid Map.”

Lowy Institute (2025). “Three-Way Energy Play: The India-Sri Lanka-UAE Deal in Trincomalee.” Interpreter.

Observer Research Foundation (2024). “The Changing Nature of Chinese Influence in Sri Lanka and Maldives.”

Rahman, A. F. M. M. (2024). “India’s Extraordinary Support during Sri Lanka’s Crisis: Motivations and Impacts.” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs.

Samarajiva, R. (2025). “Redrawing the Map of Power in the Indian Ocean.” East Asia Forum.