Atomic Cities, Divergent Futures: Unpacking the Twin Recoveries of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In the narrative of catastrophe and recovery, Hiroshima and Nagasaki stand as mirror images, shattered differently. Reduced to ruins within three days of each other in August 1945, both cities bore the unprecedented horror of nuclear warfare—yet in the years that followed, they would craft fundamentally divergent paths of reconstruction. Through creating a peace-centric urban identity, Hiroshima structured its recovery around collective mourning and global diplomacy. While equally scarred, Nagasaki elected a quieter rebirth, intertwining memory with pluralistic culture and transnational engagement. The result is an underexplored asymmetry: although both cities were dealt a similar blow, their respective policies and identities evolved in sharply contrasting directions. This article presents an analytical "apple-to-apple" comparison between Hiroshima and Nagasaki, reframing their recoveries as distinct policy case studies with implications for post-crisis urban planning, identity construction, and soft power accumulation. Their stories reveal that physical reconstruction is only half the recovery—ideological reconstruction is the other, perhaps more enduring, half.

Destruction as a Shared Origin: Statistical Baselines for Comparison

The comparable devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki creates a unique analytical foundation. Hiroshima was struck on August 6, 1945, by the uranium-based "Little Boy," detonating 600 meters above the city center. The result was apocalyptic: approximately 70,000 to 80,000 people died instantly, with total deaths by year-end estimated between 110,000 and 166,000. The city lost over 90% of its doctors and nurses and nearly 70% of its buildings. Nagasaki, hit on August 9 by the more powerful plutonium bomb "Fat Man," experienced a more geographically constrained destruction due to the hilly topography. Yet the outcome was still devastating: between 40,000 and 75,000 deaths occurred, and the Urakami district—home to Christian institutions, military facilities, and civilian populations—was annihilated. Damage encompassed over 6.7 square kilometers, with approximately 36% of Nagasaki's structures destroyed.

From these shared metrics—casualties, infrastructure collapse, and demographic displacement—it would be reasonable to assume that both cities might follow similar recovery models. Instead, what unfolded was a fascinating divergence. Hiroshima seized its tragedy as a political and economic instrument, transforming itself into a peace advocacy capital. Nagasaki, initially hesitant to fixate its identity on the atomic tragedy, strategically embedded its recovery within broader narratives of international culture and trade. Therefore, their trajectories reflect physical renewal and divergent ideological, cultural, and economic choices.

Hiroshima: Building Peace into the City's DNA

Hiroshima's reconstruction was driven by a bold state-level commitment to transform the city from a site of annihilation into a living symbol of peace. The 1949 Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law institutionalized this identity. This legislation was not merely symbolic—it enabled national funding for reconstruction, designated Hiroshima as a city of special historical significance, and reinforced its status as a permanent testament to the horrors of nuclear warfare. Urban planning decisions reflected this. At the city's hypocenter, planners left the skeletal dome of the Industrial Promotion Hall intact—a decision that would evolve into the iconic Genbaku Dome. Surrounding it, Peace Memorial Park was developed through an international design competition won by architect Kenzo Tange. By 1955, the Peace Memorial Museum opened to global visitors, offering archival evidence, survivor testimonies, and a chilling yet dignified narration of the event.

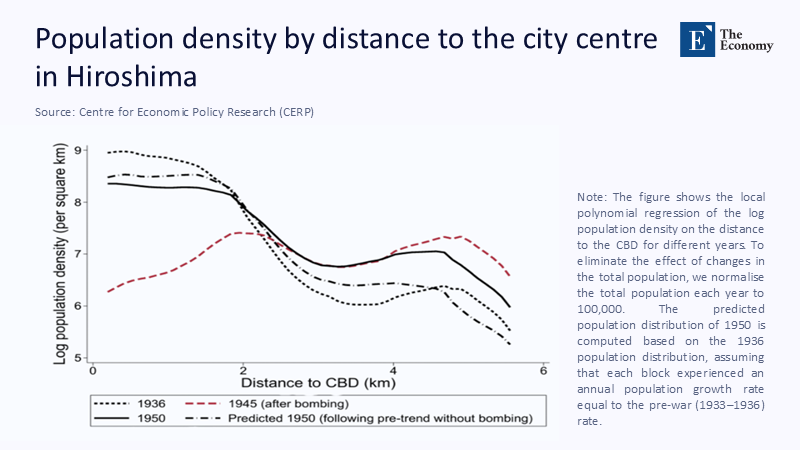

Quantitatively, the city rebounded with startling speed. By February 1946, Hiroshima's population had grown to approximately 146,000—nearly doubling from its immediate post-bomb low of 83,000. Over the next decade, Hiroshima recovered its pre-war population of 350,000 and exceeded it. International aid played a role: the Hiroshima Peace Center and various foreign-funded initiatives boosted recovery and symbolism simultaneously. Notably, the Japanese state invested in making Hiroshima a "moral capital," even as Tokyo remained the administrative one. This branding—conveyed through educational curricula, commemorative events, and foreign diplomacy—generated substantial economic benefits, particularly through tourism and international conferences. However, this resurgence wasn’t merely symbolic or policy-driven—it was spatially visible in how population patterns were reconstituted around Hiroshima’s pre-war urban core. As shown in Figure 1, the population density by distance from the central business district (CBD) reveals a striking trend: while the 1945 pattern shows a population vacuum at the city center, by 1950, Hiroshima’s density had returned toward a near pre-war configuration, especially within 2–3 km of the CBD. This strongly suggests that the city’s decision to memorialize its center, rather than relocate or decentralize, played a pivotal role in accelerating population re-agglomeration. By the 1990s, Hiroshima received more than 1.5 million domestic and international visitors annually, many drawn by its symbolic status and memorial infrastructure.

However, Hiroshima's recovery was not solely driven by economic goals. The policy vision was narrative: to prevent the erasure of suffering by institutionalizing it within public consciousness. The city created a form of "soft power urbanism," exporting peace ideology and humanitarian leadership while drawing inward the global community. The Peace Declaration, read annually by the mayor on August 6, encapsulates this enduring civic mission. For Hiroshima, the past was not a site to move on from—it was a resource to be deployed.

Nagasaki: Cultivating Pluralism and Trade in the Shadow of Silence

Nagasaki, while equally a victim of atomic horror, pursued a subtler recovery strategy. While the city initially lagged behind Hiroshima in terms of both population regrowth and infrastructural investment, it soon charted a distinctive course. The crucial difference was ideological: whereas Hiroshima centralized its identity around the atomic event, Nagasaki's leadership actively resisted becoming solely a symbol of victimhood. Instead, Nagasaki's recovery policy rested on a framework of cultural cosmopolitanism, historical pluralism, and economic reintegration.

This approach culminated in the 1949 International Culture City Construction Law—a less discussed but equally transformative policy than Hiroshima's. The law designated Nagasaki as a site of international cultural exchange, drawing on the city's historical status as Japan's earliest and most enduring portal to Western influence. From the Portuguese and Dutch traders of the 16th and 17th centuries to the flourishing Catholic community centered in Urakami, Nagasaki had long been a city of intersections. Post-1945 reconstruction leveraged this heritage, rebuilding the Immaculate Conception Cathedral in 1959, reinstituting Christian schools, and integrating Western architectural forms into public buildings. Simultaneously, the Nagasaki Peace Park—established in 1955—was designed not as a central civic monument but as a distributed memorial landscape, allowing memory to co-exist with daily life rather than dominate it.

Economically, Nagasaki invested in diversified sectors: shipbuilding (via Mitsubishi Heavy Industries), ceramics, and port logistics. While it received less international aid than Hiroshima, its integration into trans-Pacific and Southeast Asian trade networks ensured long-term economic viability. By 1960, Nagasaki's GDP per capita had begun to outpace Hiroshima's, fueled by commercial exchange rather than peace tourism. This approach reflects an alternative model of urban resilience: one that avoids a singular civic narrative, instead embracing multiplicity.

Moreover, Nagasaki's treatment of its hibakusha population was similarly integrative. While Hiroshima emphasized collective mourning through centralized memorials and registries, Nagasaki embedded survivor welfare into general healthcare and social service systems. The city's officials worked quietly with national ministries and the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission to provide medical support, but without foregrounding atomic identity as the dominant theme. In turn, this arguably reduced the stigmatization of survivors and helped foster a more inclusive civic environment.

Comparative Analysis: One Catastrophe, Two Policies

At first glance, the recovery models of Hiroshima and Nagasaki might appear to converge: both cities built peace parks, cared for survivors, and eventually welcomed tourists and foreign dignitaries. But beneath this surface lies a sharp policy divergence with profound implications. Hiroshima's narrative can be classified as "monumental recovery"—a model where symbolic memory anchors economic and political renewal. Nagasaki exemplifies "plural recovery," where atomic memory is one node among many in a complex urban identity.

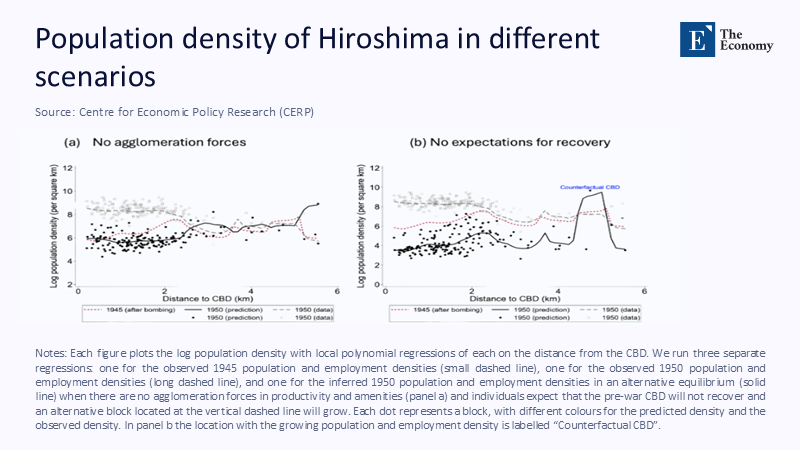

To better understand how civic expectations shaped spatial recovery, consider the contrasting scenarios modeled in Figure 2. When Hiroshima’s recovery is simulated under two counterfactuals—one with no agglomeration forces and one assuming no expectation of CBD recovery—the population density remains dispersed and fails to centralize. However, the 1950 data reflect a much more concentrated rebound, consistent with the hypothesis that collective belief in Hiroshima’s resurgence as a Peace City and policy reinforcement drove urban clustering back to the core.

Statistical evidence underscores this difference. According to city data, Hiroshima's Peace Memorial Museum attracted over 1.74 million visitors in 2018—nearly triple the number visiting Nagasaki's Atomic Bomb Museum that year (approximately 600,000). However, at various postwar junctures, Nagasaki's GDP per capita, ship exports, and industrial output have matched or exceeded Hiroshima's due to its port-based trade resilience. Tourism versus trade, remembrance versus cultural pragmatism—these binaries reflect differing policy priorities.

Politically, Hiroshima became a central figure in anti-nuclear diplomacy. Its mayor is often invited to international summits, and the city is home to various NGOs promoting nuclear disarmament. Nagasaki's approach has been less diplomatic and more academic and spiritual. Hosting Catholic symposiums, international university partnerships, and East-West cultural festivals, Nagasaki reinvested in the exchange of values rather than symbols. Significantly, both cities influenced Japan's overall peace identity via different mechanisms.

The Policy Lessons of Divergent Urban Resilience

In comparing Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we encounter two recovery models born of the same trauma. One chose to build an identity around that trauma, transforming it into civic doctrine; the other decided to remember but not be defined by it. This divergence offers invaluable lessons for modern urban policy. The post-crisis recovery is not simply a matter of rebuilding physical structures—it is a profound narrative process shaped by decisions about what to remember, what to forget, and how to construct meaning in the aftermath of loss.

For policy architects, planners, and educators, the implications are far-reaching. Should cities capitalize on their histories as economic and political resources? Or should they absorb catastrophe into a more plural, forward-facing identity? Hiroshima and Nagasaki offer both models—successful, complex, and instructive. The choice between monumental memory and distributed identity is not binary but requires clarity. The Hiroshima and Nagasaki case studies underscore that recovery is as much about narrative coherence as bricks and budgets for future cities facing crises, whether war, climate disasters, or pandemics.

The original article was authored by Kohei Takeda and Atsushi Yamagishi. The English version of the article, titled "Hiroshima: Resilience of city structure after the atomic bombing," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Cheng, Lan. "Nuclear Shadows: Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the Divergent Recovery of Atomic Cities." Stanford PH241, 2018.

Diehl, Daniel. "From Atomic Wasteland to Cultural Capital: Nagasaki's Postwar Transition, 1945–1950." ResearchGate, 2012.

Fujii, Satoshi. "Reconstruction and Peace Memorial City Planning." Journal of Urban History, 2005.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum Annual Report, 2018.

Nagasaki City Government, GDP and Population Reports, 1960–2020.

Nobel Peace Prize News Archives, 2023–2024.

RERF. "Hiroshima and Nagasaki Mortality Figures." Radiation Effects Research Foundation, 2020.

Yamazaki, Jiro. "City of Peace: Hiroshima's Urban Planning Legacy." Planning Perspectives, 2011.