When Banks Retreat: Why Nonbanks Now Anchor the Credit Safety Net

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Regulation made banks safer—but it also made them spectators. The decisive flows that keep factories humming and payrolls met during a shock now originate with actors that, two decades ago, did not merit a footnote in the stability playbook. That brutal inversion—deposit-backed institutions retreating while nonbank lenders surge—anchors this column. It poses a stark policy dilemma: how to reconcile rigid macro-prudential rules with the economy's growing dependence on intermediaries that sit outside Basel and, often, beyond the routine gaze of supervisors. The answer is neither to loosen the screws on banks nor to let the new players roam unchecked. It is to urgently build an intentional, three-tiered rescue architecture in which public and private nonbanks are pre-positioned, transparent and capitalized to take the first hit when crisis strikes, leaving banks free to protect the payments system rather than gamble on risky corporate turnarounds.

From back-office footnote to primary dealer of last resort

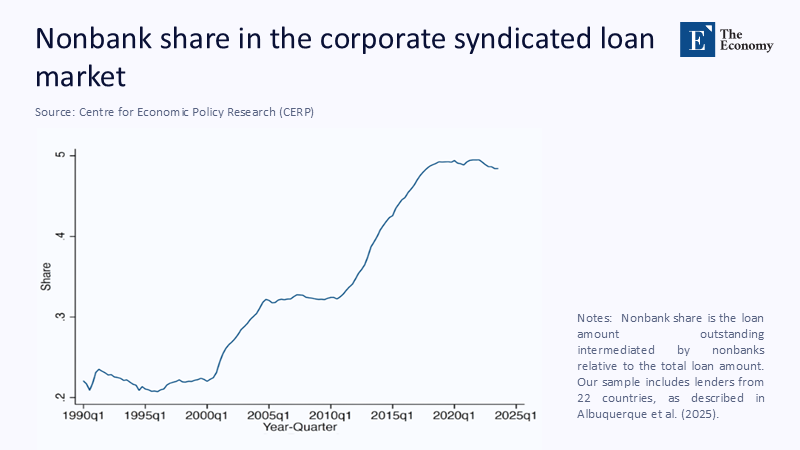

Even before the onset of COVID-19, a significant shift in the credit pendulum was underway. Global syndicated loan data from 22 jurisdictions reveal a steady rise in the nonbank share, which climbed from a modest fifth in the early 2000s to nearly half of the outstanding volumes by 2023. This shift, marked by its visual and emphatic nature, results from policy-induced changes.

This chronology of the credit market aligns with waves of regulatory tightening. The introduction of Basel II in 2004, followed by Basel III in 2010, and the subsequent imposition of systemic-risk surcharges and borrower-based limits by national authorities have all widened the gap between bank capital charges and the unregulated cost of equity available to private credit funds, insurance affiliates, and business-development companies. As a result, the Bank for International Settlements now estimates private credit assets under management to be above US $2.5 trillion—roughly five times the level in 2010 and on par with the global high-yield bond market.

The numbers alone understate behavioral change. Whereas pre-GFC crises drew on bank-arranged rescue consortia—think Citigroup'sCitigroup's role in Mexico (1995) or JPMorgan'sJPMorgan's in LTCM (1998)—the post-Basel III world sees bespoke vehicles spring up outside the deposit system. For example, Prudential Financial'sFinancial's PGIM unit signed a US $500 million forward-flow agreement with Affirm in 2025, in effect financing up to US $3 billion of buy-now-pay-later receivables without a dollar of insured deposits on the line. That transaction is no outlier; Blackstone'sBlackstone's BCRED business-development company managed more than US $80 billion by March 2025, part of a sector whose dry powder now exceeds US $400 billion. This shift in power and responsibility to nonbank lenders is a significant aspect of the new financial hierarchy.

The elasticity paradox: policy shocks shrink bank loans but swell nonbank credit

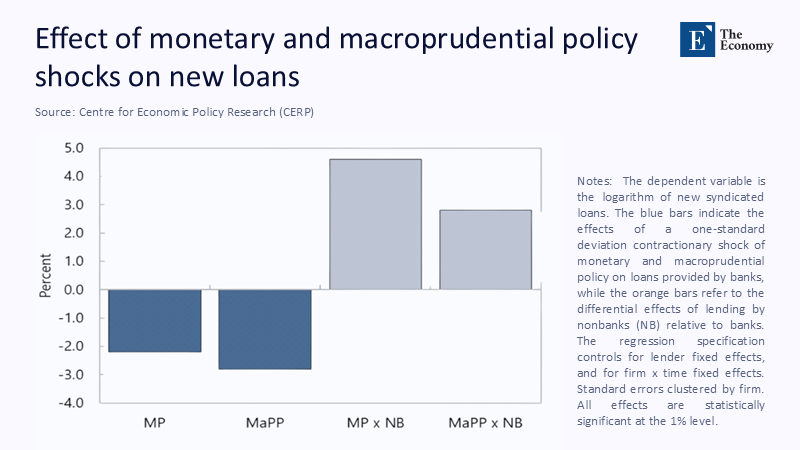

Econometric work by Albuquerque and co-authors offers clean identification of what practitioners long suspected: a one-standard-deviation contractionary macro-prudential shock reduces new bank loans by nearly 3% within the quarter yet raises nonbank lending to the same borrowers by around 4½%. The authors interpret that offset as migration rather than mitigation.

Understanding the ''credit-elasticity paradox'' is crucial for maintaining stability. The marginal dollar of late-cycle lending, which originates from balance sheets that allow for higher leverage, lighter liquidity buffers, and redemption options that mimic runnable deposits, poses a significant risk. BIS analysts caution that only about 40% of US private credit funds employ third-party valuation agents, raising concerns about mark-to-model illusions in a downturn. A market that reallocates risk without clear price discovery creates fresh fault lines, even as it eases pressure on Basel-constrained banks.

Covid-19: a live-fire test of the new hierarchy

The pandemic delivered an unplanned stress test of this architecture. In the United States, the Paycheck Protection Program approved US $793 billion in loans; as of late 2024, US $763 billion—96%—had already been forgiven. Europe booked €940 billion in state-backed guarantees under the EU's Temporary Framework. During the same window, the IMF committed the foreign-currency equivalent of US $294 billion across 96 countries. In addition to that, roughly US$ 350 billion was estimated by Federal Reserve researchers for private-credit managers deployed in 2020-21. The conclusion writes itself: more than half of the liquidity that kept firms solvent flowed outside the deposit-taking sector.

Critically, the IMF has since secured a 50% quota increase—SDR 238.6 billion, or almost US $320 billion—ratified in December 2023. Thus, Multilateral lenders are beefing up precisely as national treasuries and private funds enlarge their firepower. The pieces of a layered backstop already exist; what is missing is the connective tissue that assigns responsibility ex-ante and enforces transparency symmetrically across charters. This transparency makes the audience feel reassured and confident in the proposed system.

Designing a three-tiered safety net

Tier I: Multilateral insurance. With the quota uplift, total permanent IMF resources will rise to nearly US $960 billion—enough to roll over Ukraine-scale emergencies for multiple members simultaneously. To hardwire counter-cyclical support, future Special Drawing Right (SDR) allocations should link distribution keys to real-time indicators of pandemic or climate shocks rather than simply gross national income.

Tier II: National corporate stabilization funds. Domestic SPVs, funded by GDP-linked sovereign notes during calm periods, would auto-activate once high-yield spreads breach a two-sigma threshold. Because they sit outside banking regulation, drawing on the facility would not trigger Pillar-1 capital surcharges that deter banks from renewing working capital lines.

Tier III: Market-based capital with gated liquidity. Private credit funds could receive tax deferrals on carried interest in exchange for adopting redemption gates that trip automatically when system-wide credit VaR exceeds a set percentile. The gates would mimic the time-varying reserve requirements of early-20th-century US national banks—unfashionable but effective speed bumps against runs.

Case studies: Korea 1997, Greece 2010, Silicon Valley 2023

History validates the layered approach. When Asian corporates lost dollar funding in 1997, the IMF supplied the hard currency; domestic merchant banks, unburdened by Basel rules, refloated exporters with won-denominated receivable-backed paper. Fast-forward to the euro-area crisis, and the pattern repeats: ECB haircuts on Greek sovereign collateral froze local banks just as private European distressed-debt funds began scooping up shipping-company loans at 70 cents on the euro. Most recently, the 2023 Silicon Valley mini-panic saw regional banks shutter tech credit lines while nonbank revenue-based financiers advanced cash against annual-recurring-revenue contracts within days. The common thread is simple: the lender with the least regulatory friction fills the breach. Policy can ignore that reality or harness it.

What educators must do now?

The moment to integrate programs that still teach banking and capital markets as siloed disciplines has arrived. Coursework should move beyond legacy capital-asset pricing models to blended cost-of-capital frameworks that explicitly price sovereign guarantees and fund-level liquidity risk. Empirical finance electives can teach student teams the task of replicating the Albuquerque regression with new panel data that includes BDC leverage; risk-management classes must introduce haircut elasticity and redemption-coverage ratios as standard diagnostics alongside the Basel liquidity coverage ratio. Finally, public finance seminars should explore GDP-linked notes and auto-trigger SPVs as practical instruments, not exotic footnotes.

Toward a new social contract for credit

The last fifteen years have delivered a paradox: every dollar of additional capital regulators forced into banks ultimately transferred crisis lending to entities with lighter oversight. That is not an argument for unwinding Basel III; it is a call to acknowledge displacement and to govern it. A deliberate three-tier network—multilateral, sovereign, and private—can align incentives, price liquidity realistically, and preserve banks ' payments function without sendingencing the real economy to a funding cliff each time risk appetites turn.

The next crisis will not wait for another multi-year round of policy reflection. Legislators, supervisors, and the academy must act now to codify responsibilities, harden transparency, and educate practitioners fluent in an ecosystem where the savior of first resort is rarely a bank but, increasingly, a policy-ready nonbank. Failing that, the world may discover that making banks bulletproof can still expose Main Street.

The original article was authored by Bruno Albuquerque, a Senior economist at the International Monetary Fund, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "From banks to nonbanks: Macroprudential and monetary policy effects on corporate lending," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Albuquerque, B., Cerutti, E., Chen, N., & Firat, M. (2025). From Banks to Nonbanks: Macro-Prudential and Monetary Policy Effects on Corporate Lending. IMF Working Paper 096.

International Monetary Fund. (2023). Annual Report — Navigating Uncertainty.

European Commission. (2024). ""State-Aid Temporary Framework for COVID-19.""

Blackstone Inc. (2025). BCRED Fund Factsheet

International Monetary Fund. (2023, December 18). ""IMF Board of Governors Approves 50 Percent Quota Increase Under 16th General Review of Quotas.""

U.S. Small Business Administration / ProPublica. (2024, October 27). ""Tracking PPP: Amount Approved and Forgiven.""

Bank for International Settlements. (2025, March). ""The Global Drivers of Private Credit,"" BIS Quarterly Review.

Prudential Financial Inc. (2025, June 18). ""PGIM Fixed Income Lends $500 Million in Private Credit to Affirm."" Wall Street Journal.