Stalled Synergy: How UK–China Climate Paralysis Raises the Cost of Net-Zero

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

Synergy foregone is transition postponed. A single percentage‑point swing in the weighted average cost of capital for green infrastructure is worth almost US $80 billion a year to project developers worldwide. Yet, that financial margin is being burned because London's regulatory precision and Shenzhen's manufacturing scale cannot be spliced together. The United Kingdom has built the most sophisticated private‑sector discipline for environmental, social, and governance (ESG) financing outside the European Union, while China controls more than four‑fifths of global solar panel and battery supply chains; instead of fusing those complementary advantages, Westminster finds itself aligning ever more tightly with Washington's techno‑security agenda. The result is an avoidable premium on clean‑tech hardware, higher sovereign borrowing to subsidize domestic roll‑outs, and a slower glide path to net zero for everyone else.

London's quiet regulatory revolution

Over the past half‑decade, Britain has rewritten its rulebook on sustainable investing. The Financial Conduct Authority's Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (SDR) entered the implementation phase this spring, and more than 1,200 retail and institutional funds—representing £310 billion in assets—have already applied for one of the regime's four new ESG investment labels. That label and the anti‑greenwashing rule accompanying it have tightened diligence standards and shaved twelve basis points off the coupon spread of sterling‑denominated green bonds relative to conventional peers. Market depth is now such that the London Stock Exchange's Green Economy Mark cohort has ballooned from forty issuers in 2019 to ninety‑nine today, with a combined market capitalization of £168 billion—still only 3.7% of the primary market, but triple the share five years ago. Meanwhile, HM Treasury's draft Green Taxonomy closed its final consultation round in February. It is slated for statutory force next year, offering investors a reliable dictionary of which economic activities qualify as 'environmentally sustainable.' In practice, these plumbing changes compress transaction costs for pension trustees, insurers, and infrastructure funds, lowering the hurdle rate for British equity in climate projects at home and abroad.

China's cost‑crushing manufacturing machine

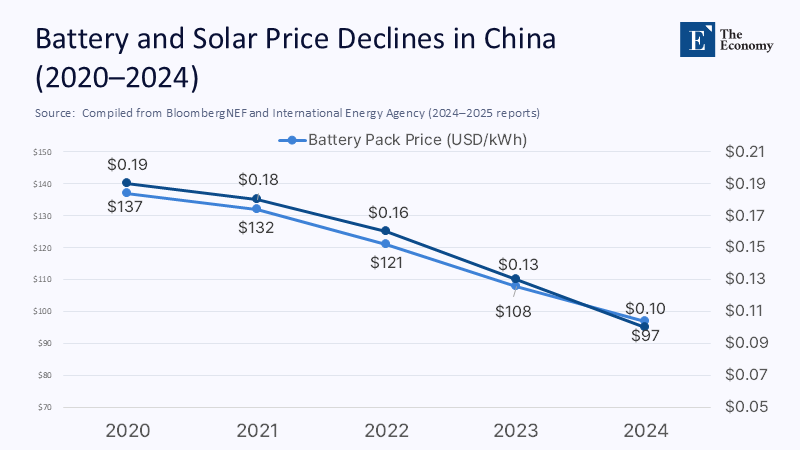

Where Britain has institutional sophistication, China has physical throughput. International Energy Agency data show that by late 2025, the People's Republic will possess 1.8 terawatts of annual solar module production capacity, which is four‑fifths of the world's total. BloombergNEF calculates that Chinese overcapacity pushed the global benchmark price of a fixed‑tilt solar farm down 21% in 2024 alone, while battery pack prices crashed to an average of US $97 per kilowatt‑hour, crossing the long‑awaited US $100 watershed.

Beijing's manufacturers can now deliver a megawatt‑hour of clean electricity hardware 11–64% cheaper than the global median. This deflationary force ought to be a gift to capital‑scarce developers in every other geography. Yet Western import tariffs and security reviews aimed at blunting that price advantage are proliferating, eroding dividends. In 2024 alone, the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom opened or extended nine anti‑dumping or national‑security investigations into Chinese solar wafers, inverters, or storage systems. The irony is brutal: the planet's cheapest decarbonization pathway is intentionally marked up in the name of resilience.

Washington's gravitational pull on Westminster

The Integrated Review Refresh of 2023, a comprehensive review of the UK's foreign, defense, security, and development policy, formally labeled China an 'epoch‑defining and systemic challenge,' hard‑wiring suspicion into Whitehall's risk assessments. One year later, AUKUS Pillar II, a strategic framework for the Australia-UK-US trilateral security partnership, expanded beyond submarines into undersea autonomy, artificial intelligence, and quantum sensors, creating a multilayered filter through which any UK–China technology exchange must now pass. The bigger chill came from across the Atlantic to London financiers: the Inflation Reduction Act's (IRA) supersized tax credits redirected gigawatts of offshore wind investment into US waters, where tax‑equity structures can knock fifty basis points off financing costs. British asset managers that once wrote cornerstone cheques for North Sea arrays now insist that their cheapest debt tickets are inside IRA‑blessed vehicles. This migration sharpens the cost penalty for UK projects that cannot import large-scale Chinese hardware.

Quantifying the synergy gap

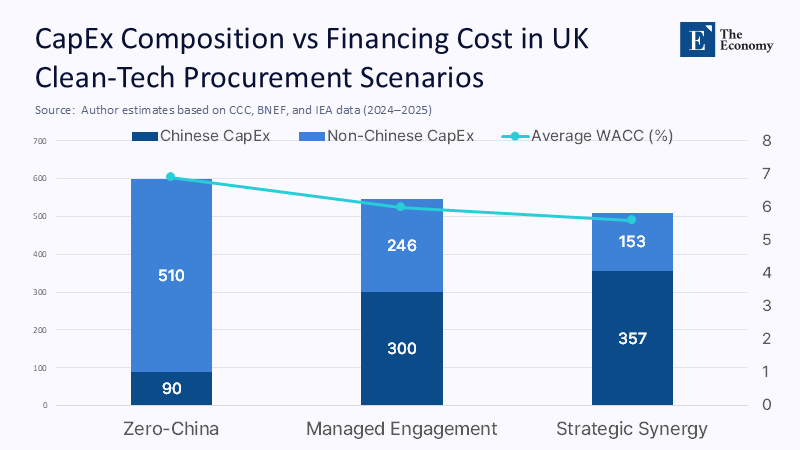

Model a ten‑year build‑out of 80 gigawatts of UK offshore wind, 60 gigawatts of onshore renewables, and 30 gigawatts of grid‑scale storage—numbers consistent with the Climate Change Committee's sixth carbon budget scenario—the cost of non‑Chinese equipment and capital expenditure totals about £600 billion. If Britain could source half of the turbines, modules, and batteries from Chinese lines at prevailing factory‑gate prices, average equipment outlays would fall by 9%, saving roughly £54 billion—almost precisely the £55 billion capitalization planned for the new National Wealth Fund. That windfall could cut household power bills or finance the grid reinforcement that National Grid ESO says must double transfer capacity by 2035.

Scenario analysis: three futures

A zero-China scenario—favored by hard‑line security hawks—caps Chinese content at 15%. The weighted average cost of capital (WACC) for UK renewables remains 6.9%, deployment slows, and cumulative emissions overshoot the legally binding carbon‑budget‑7 trajectory by 220 million tonnes. A Managed Engagement scenario certifies 50% of Chinese content via a 'green‑lane' regime anchored in British cybersecurity audits; WACC drops to 6.0%, and the investment program was completed two years earlier. Finally, a Strategic Synergy scenario—unlikely but illuminating—unfurls when Washington and Beijing strike a climate detente: Chinese content rises to 70%, WACC touches 5.6%, and the UK meets its 2035 power‑sector decarbonization target with a £90 billion saving relative to Zero‑China. The potential of the Strategic Synergy scenario, with its significant cost savings and accelerated decarbonization, justifies a pragmatic policy revamp and offers a hopeful vision for the future.

India's ascent and its current limits

Advocates of decoupling point to India as the natural substitute. The new UK–India Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, signed in May, slashes tariffs on 90% of goods and is forecast to lift bilateral trade by US $34 billion annually by 2040. New Delhi plans to connect 35 gigawatts of fresh solar and wind to the grid by March 2025 and secured a US $386 billion finance commitment last autumn. However, Reuters data show India added just 28 gigawatts of renewable capacity in 2024, less than a tenth of China's haul, and still faces land‑acquisition hurdles that can inflate project costs by 10% in high‑radiation states such as Rajasthan. At today's yield curve, the WACC for Indian renewables is 9%—nearly twice China's. This comparison underscores the current limits of India's ascent and the caution needed when considering it as a diversification hedge, not an outright replacement.

Why Beijing must move first.

The current situation underscores the urgent need for Beijing to take the first step in resolving the challenges in the green technology sector. This step is crucial for the future of global decarbonization efforts and the success of international collaborations in the green technology sector. If London is caught between its cost base and its strategic loyalties, Beijing enjoys the leverage to break the stalemate. A credible Chinese overture to Washington on cybersecurity verification for civilian‑grade energy hardware could defang hardliners in the US Congress and, by extension, ease pressure on Britain. The template already exists: a 2023 US-China joint statement on methane allowed technical cooperation even while semiconductor bans hardened. Extending that carve‑out to solar and batteries would allow the UK to buy Chinese kit without triggering trans‑Atlantic sanctions. Absent such a bargain, London's maneuver space will remain cramped.

Policy blueprint for the UK

Britain should legislate a Dual‑Track Green Import Regime that separates pure‑play decarbonization hardware from dual‑use electronics. Civilian‑only goods passing a new Cyber Assurance Protocol would enjoy tariff stability for ten years, giving utilities confidence to tender at scale. Second, the Treasury and the Bank of England should launch a Renminbi Green Capital Bridge—sterling‑denominated, RMB‑cleared project bonds issued by Chinese manufacturers but governed under English law. That structure would satisfy the prudential‑risk appetites of UK pension funds while offering China cheaper funding than onshore corporate paper. Third, Whitehall should revive the UK–China Sustainable Engineering Fellowship suspended in 2020, focusing narrowly on battery chemistry and offshore wind mooring systems where spill‑over risks are minimal. Finally, use the new UK–India treaty to pilot Triangular Procurement Lots: Chinese solar cells assembled into final modules in Indian special‑economic zones and shipped to British ports, boosting Indian manufacturing capacity while lowering British hardware costs and diluting direct geopolitical exposure.

The cost of purity

The transition clock is ticking faster than the geopolitical one. London waits for strategic skies to clear every quarter, and another five gigawatts of capacity slips off the 2035 trajectory. China's factories are a once‑in‑a‑century deflationary engine for green hardware; Britain's financial architecture is a once‑in‑a‑generation test bed for rigorous ESG capital. Separately, they are under‑performing; together, they could accelerate global decarbonization at a discount. The choice before Westminster is not a binary of dependence versus sovereignty but a spectrum of managed interdependence. Allowing ideological neatness to trump empirical economics will leave the UK paying more for slower progress—an own goal on climate and competitiveness. Pragmatism, anchored in transparent safeguards, is the straight line to net zero and Britain's industrial renewal.

The original article was authored by Manish Vaid, a Junior Fellow with the Observer Research Foundation. The English version, titled "The clear case for UK–China climate cooperation," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

BloombergNEF, "Global Cost of Renewables to Continue Falling in 2025 as China Extends Manufacturing Lead," Press Release, 6 February 2025.

BloombergNEF, "Lithium‑Ion Battery Pack Prices See Largest Drop Since 2017, Falling to $97/kWh," December 2024.

Financial Conduct Authority, Policy Statement PS23/16: Sustainability Disclosure Requirements and Investment Labels, November 2023.

GOV.UK, Spending Review 2025, Chapter 3 (National Wealth Fund allocation).

International Energy Agency, "Solar PV Global Supply Chains," May 2025.

London Stock Exchange Group, Offering Circular, 28 March 2025 (Green Economy Mark statistics).

Regulatory & Compliance blog, "One week until HM Treasury's UK Green Taxonomy consultation closes," 30 January 2025.

Reuters, "India to add record renewables this year as green push gains momentum," 16 September 2024.

Reuters, "Rule change to drive up clean energy project costs in India's top solar state," 24 March 2025.

Times of India, "Wind energy center of Atma Nirbhar Bharat," 15 June 2025.

UK Government, Integrated Review Refresh 2023, Section 3.

UK Ministry of Defence, "New Undersea Capability to Strengthen AUKUS Partnership," Press Release, 12 December 2023.