A Vacancy at the Head Table: Why the G7 Cannot Afford to Become a G6

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

When Donald Trump's helicopter lifted from Kananaskis at dawn on 16 June 2025, the summit's center of gravity went with it. Schedule grids that had taken Canadian officials a year to engineer imploded in minutes; six heads of government found themselves trapped inside a conference architecture designed around a missing pillar. That rupture did not simply embarrass the hosts. It illuminated a structural reality that policy circles have half-acknowledged for years and yet rarely state aloud: without the United States, the Group of Seven is neither seven nor a group—nor especially relevant. As tariff walls harden, wars metastasize, and rival coalitions court the Global South, the G7's flirtation with life as a "G6" is not a theoretical exercise. It is a stress test the West is failing in real-time.

The Summit That Wasn't — A Statistical Autopsy

Early departures are not unknown in summitry—Nixon left the 1973 Paris talks early, and Boris Yeltsin once skipped a day at the 1997 Denver G8—but never has an exit torn such a hole in the fabric of an event. By lunchtime on the 16th, working sessions on infrastructure finance, critical minerals, and WTO reform had been truncated or folded into side meetings as officials scrambled to avoid commitments that would require an absent American signature. Canadian organizers quietly canceled the high-profile "Re-Free-Trade" plenary, while negotiators struck three of the five paragraphs on maritime security from the draft communiqué. French broadcaster RFI counted fifteen agenda items either dropped or dramatically shortened; its correspondent called the mood "stunned and directionless."

The opportunity cost is quantifiable. Sherpa's background papers identified five domains—digital infrastructure, vaccine manufacturing, debt relief, green bond issuance, and WTO reform—as the highest-multiplier interventions for low-income economies. Between 2020 and 2024, the G7 funneled roughly US $122 billion into those buckets; US agencies supplied 57%. Remove Washington's checkbook; last year's collective commitments collapsed by almost three-fifths. No ad-hoc coalition can patch a wide funding hole in one weekend behind the Rockies.

Power in Numbers: The United States as Statistical Hinge

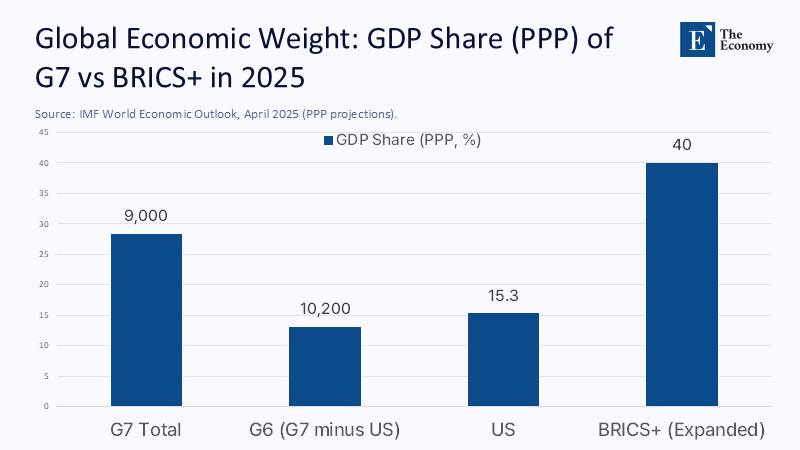

The United States as the Statistical Hinge. Proponents of a streamlined G6 insist the remaining members would still outrank China economically, citing purchasing-power-parity tables that group Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Japan, and Canada into a bloc worth roughly US$24 trillion. Yet the April 2025 IMF DataMapper tells a harsher story. The entire G7 commands 28.4% of global output in PPP terms; the United States alone contributes 15.3 percentage points of that share. Subtract Washington and the putative G6 slides to 13.1%—barely a third of the 40% the enlarged BRICS will command next year.

Trade flows widen the gap. G7 merchandise exports 2024 totaled about US$ 5.8 trillion, but 43% moved under a US flag. Remove American cargo, and the G6 would rank behind both BRICS-plus and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in goods shipped, forfeiting critical mass in rule-setting fora from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development to the WTO. The digital-economy deficit is deeper still: US firms host seven of the ten largest cloud platforms and fund 60% of global R&D in artificial intelligence and quantum computing. Research consortia drafting "critical technology" standards do not queue for a forum from which those firms are absent.

Beyond raw output, Washington anchors the global financial plumbing that makes G7 pronouncements actionable. The dollar denominates 58% of world foreign exchange reserves and almost 90% of commodity trade. Every G7 financial-stability communiqué since 2008 has hinged on the Federal Reserve's willingness to expand swap lines; when the Fed opened nine emergency facilities during the Covid-19 liquidity shock, Swiss and Japanese banks cleared nearly one-third of their dollar liabilities overnight. Strip away that backstop, and the G6 could issue stern paragraphs about capital-flow volatility—but not the liquidity to stop a crisis.

Security: The Quiet Glue That Holds the Club Together

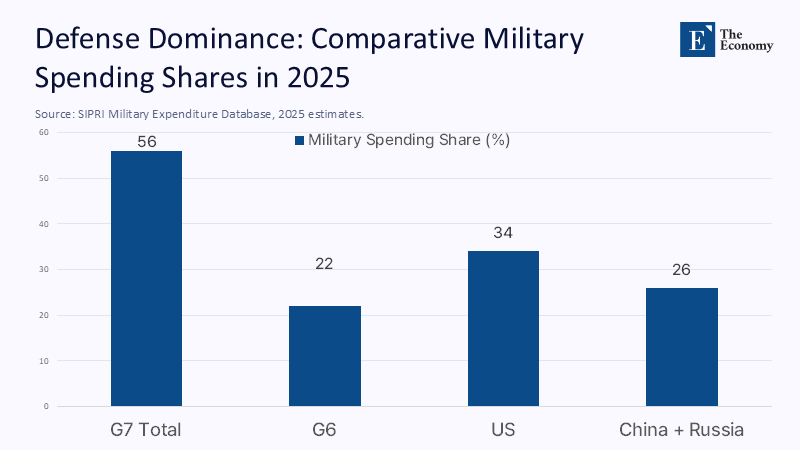

Skeptics often retort that the G7 is an economic club, not a military alliance. The Kananaskis drama itself contradicts that veneer. Under US prodding, all NATO members pledged—at least on paper—to meet the 2-percent-of-GDP defense benchmark within the year. Even this supposedly collective milestone is profoundly asymmetric: the US spends roughly three times as much on defense as the other six combined.

If Washington is removed, the G6's share of global military outlays plummets from 56% to 22%, below the combined spending of China and Russia.

Security guarantees anchor global commerce; Japanese and German supply-chain managers factor insurance costs in the Red Sea precisely because a U.S.-led coalition polices that choke point. When Trump took his guard of honor and left, draft language on maritime escorts was the first to be watered down. Europe's subsequent scramble—Paris and Berlin promising to push defense outlays to 3.5% of GDP, as outlined in their joint Financial Times essay—was an admission that the American umbrella could no longer be assumed.

BRICS: Statistical Mass, Strategic Discord

The enlarged BRICS is the rival bloc that most haunts the G7's imagination. With eleven members after the Johannesburg summit (Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE joined the original five and South Africa), it will account for around 40% of global GDP (PPP) and nearly half the world's population in 2026. Symmetry, however, is not cohesive. The grouping remains riven by structural antagonisms—Sino-Indian border clashes, Brazilian fears of Chinese soy subsidies, and Middle Eastern energy competition. Jim O'Neill, the economist who coined the acronym, warns that BRICS "risks symbolism without substance" unless Beijing and New Delhi reach a modus vivendi.

Nonetheless, heft matters in rule-making bodies. In the UN General Assembly, BRICS now commands 11% more votes than the entire OECD combined. Last year, the bloc persuaded the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank to allocate 26% of its lending to non-aligned climate projects. This share gravitated toward G7-guided corridors like the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment. The message to the developing world is simple: multiple checkbooks exist. A G6 with slimmed-down fiscal firepower will struggle to compete.

Trade Fragmentation and the Cost of Leaderless Liberalism

The World Bank's June 2025 Global Economic Prospects warns that if tariff escalation continues at its current pace, global output will undershoot its potential by 2.3% in 2026. That drag will land hardest on export-oriented economies plugged into US value chains—Germany's machine-tool makers, Japan's semiconductor equipment suppliers, and Italy's sand and luxury firms. A G6 can deplore protectionism but wields little leverage over the regulatory levers that trigger it.

Critical minerals illustrate the point. One month before Kananaskis, a CSIS paper urged the G7 to create a shared insurance window so African and Latin American producers could diversify beyond a single Chinese buyer. Yet investment insurers in Ottawa or Rome remain reluctant to underwrite nickel mines in the DRC or lithium projects in Bolivia without the US International Development Finance Corporation's guarantee. Europe may dream of "strategic autonomy," but its risk-management architecture was built atop American sovereign credit.

The Dollar Hegemony That Dare Not Speak Its Name

Dollar dominance is often treated as a background condition, yet it permeates every policy lever the G7 tries to pull. Last year, when Treasury Secretary Alejandro Castillo threatened secondary sanctions on banks processing Russian crude above the G7 price cap, the measure stuck because 88% of those transactions cleared through dollar correspondent networks. A purely European price cap—mooted if Washington disengages—would demand enforcement in euros, a currency denoting less than 3% of global commodity trade. The G6 could pass the exact resolution and watch it unravel on Monday morning.

Swap-line geopolitics further exposes the asymmetry. During the March 2025 bond market wobble triggered by a cyber-attack on Taiwanese chip foundries, the Fed extended temporary dollar liquidity to five central banks. Yields on Japanese corporate bonds fell 40 basis points within two trading days; Europe's corporate debt spreads tightened in sympathy. In the absence of Washington, the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan would have had to craft bilateral swaps and hope markets believed the lines were large enough. Historical episodes—from the 1960s sterling crisis to 1997's Asian financial turmoil—suggest such confidence is seldom forthcoming.

Learning from Other Institutions

One retort to US indispensability points to multilateral bodies where America is marginal or absent: the Asian Development Bank functions with Japan in the chair; the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation survives with no Western membership. Yet neither entity claims to set global macro-regulatory norms. The ADB's capital base is less than half that of the World Bank; the SCO is a security talk-shop without collective-defence provisions. The G7's mystique derives from its ability to make other actors move—in SWIFT codes, Basel rules and anti-money-laundering blacklists. Those levers sit disproportionately in US hands.

Can the G7 Be Re-engineered? Three Pragmatic Reforms

If raw arithmetic dooms the G6 idea, the answer cannot be to plead for a return to cozy trans-Atlantic harmony—a nostalgia that events keep mocking. The G7 must recast itself so Washington's presence is structurally valuable but not singularly indispensable. Three reforms would start that pivot. First, institutionalize rotating policy leads. Let Tokyo steer artificial intelligence governance for a three-year cycle, Berlin pilot green-hydrogen standards, and Ottawa coordinate critical minerals finance. Shared ownership reduces the cliff-edge risk posed by a single walk-out.

Second, unionize toolkits. Create a G7 Development Credit Facility that pools all seven members' export-credit agencies and sovereign wealth funds. European or Japanese capital could backstop deals if Congress stalls appropriations for the US International Development Finance Corporation. Structured properly, such a facility would harness America's credit rating without making it the only guarantor.

Third, embed "continuity clauses" into summit rules so that if the chair leaves, agenda items roll automatically to deputy-level sign-offs, and final communiqués can be issued by a qualified majority. The European Union has lived with qualified-majority voting for decades; it is messy, but it prevents a single spoiled vote from wrecking every line of policy text.

The Educational Ledger: Lessons for the Next Generation of Policymakers

For students of international relations watching Kananaskis unfold, the episode offers four pedagogical lessons. First, economic weight is necessary but insufficient; legitimacy demands credible enforcement instruments. Second, global governance's concept of "club goods" is fragile when the most significant shareholder questions the club's premise. Third, numbers can mislead: a statistical bloc is not a strategic actor unless its members share enforceable norms. Lastly, policy design must consider circuit-breakers—automatic stabilizers for diplomacy—that blunt the edge of political shocks.

Relevance Through Distributed Resilience

Trump's helicopter departure was more than a diplomatic spectacle. It heralded a future in which America's engagement can never be presumed—and dared the other six to prove they can bear more weight. By every quantitative yardstick—GDP share, trade flows, military spending, innovation capacity—the United States is the hinge on which the G7 turns. Pretending otherwise courts irrelevance. Yet pretending that the grouping cannot evolve is equally ruinous.

The way forward is not to amputate the American limb nor to cling to it as a crutch. It is to distribute functions so that the G7's legitimacy grows from collective utility rather than default hierarchy. A re-engineered G7 that treats Washington as first among equals could still out-finance, out-innovate, and out-mobilize any rival bloc—but only if the lesson of Kananaskis is heeded: legitimacy in twenty-first-century governance is earned not by occupying a seat, but by staying long enough to do the work.

The original article was authored by Alan Alexandroff, a Director of the Global Summitry Project. The English version, titled "Trump’s disruption in Canada leaves the G7 at a crossroads," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Chatham House. 2025. It's time to rethink the G7.

CSIS. 2025. G7 Cooperation to De-Risk Minerals Investments in the Global South.

East Asia Forum. 2025. Trump's disruption in Canada leaves the G7 at a crossroads.

Financial Times. 2025. "Macron and Merz: Europe must arm itself in an unstable world."

International Monetary Fund. 2025. World Economic Outlook (April 2025) DataMapper.

RFI. 2025. "Trump's early departure casts shadow over G7 summit amid Middle East crisis."

Reuters. 2025. "Trump leaves G7 summit early due to Middle East situation."

World Bank. 2025. Global Economic Prospects, June 2025