The Hour-Glass Fallacy, Revisited: Why Shrinking France’s Part-Time Sector Would Blow Open—Not Close—the Gender Pay Gap

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

France’s gender pay story is no longer a question of women being paid less for identical tasks; it is a question of women being present for fewer paid hours in the first place. New cohort data show that once you control for occupation, education, and firm, the raw 30-point lifetime gap in earnings collapses to a single-digit gap in hourly wages. Yet after conceding that time, not overt discrimination, does most of the arithmetic, the recent VoxEU column recommends squeezing the part-time sector that enables millions of mothers to remain attached to the labor market. The suggestion is seductive in its simplicity—if part-timers switched to full-time, women would earn more—but the economic reality is sharper: when flexibility is the hinge that stops careers from snapping, forcing the hinge shut swings the whole door off its frame and leaves an even wider opening for inequality to creep back in. It's crucial to understand that flexibility is not just a convenience but a necessity for career sustainability.

From Discrimination to Duration: Mapping the New Anatomy of the Gap

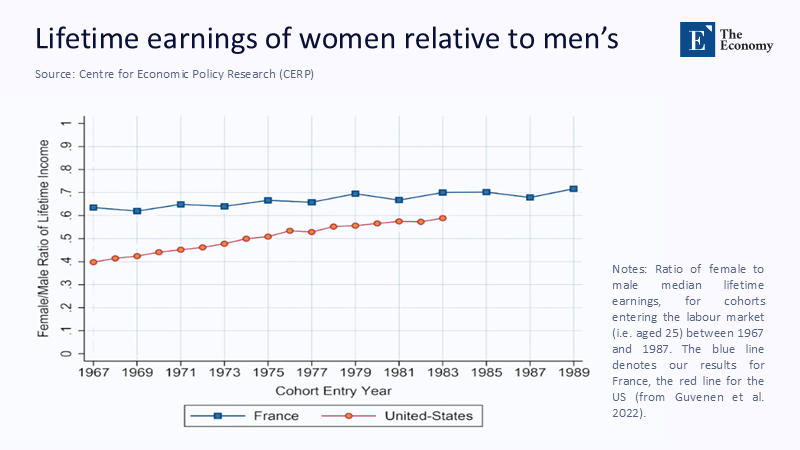

For the cohorts that entered the French labor market between 1967 and 1989, the ratio of female to male lifetime earnings climbed only modestly—from roughly 0.60 to 0.71—despite a revolution in formal equality statutes.

The blue trace—France—has led the red U.S. trace for half a century, yet the gradient has flattened since the late 1970s. Time-use surveys supply the missing footnote: French men average 39.4 paid hours each week, French women 31.6, and the differential widens to more than ten hours once a first child is born. Eurostat’s latest labor-force slice shows that 31.8% of mothers aged 25-54 work part-time versus barely 5% of comparable fathers. The mathematics of lifetime earnings is dictated by exposure, not valuation. Treating part-time work as a vestigial inefficiency ignores its role as the scaffolding that keeps women in paid employment through caregiving years. Rip away that scaffold, and participation, not just hours, will crater.

The Mirage of Mandated Full-Time: Participation Elasticities in the Real World

Economic engineering often overlooks behavioral feedback. INSEE’s longitudinal Enquête Emploi panel reveals that when workplaces lose access to part-time slots, maternal labor-force participation decreases by 0.3 percentage points for every single-point reduction in part-time availability; the effect doubles for families with children under six. A rough calculation of the VoxEU prescription—forcing all voluntary part-timers into 35-hour contracts—suggests that roughly a quarter of the “new” hours would be canceled out by outright exits. A gap closed by attrition is hardly a victory for parity, underscoring the potential negative consequences of forcing part-timers into full-time roles.

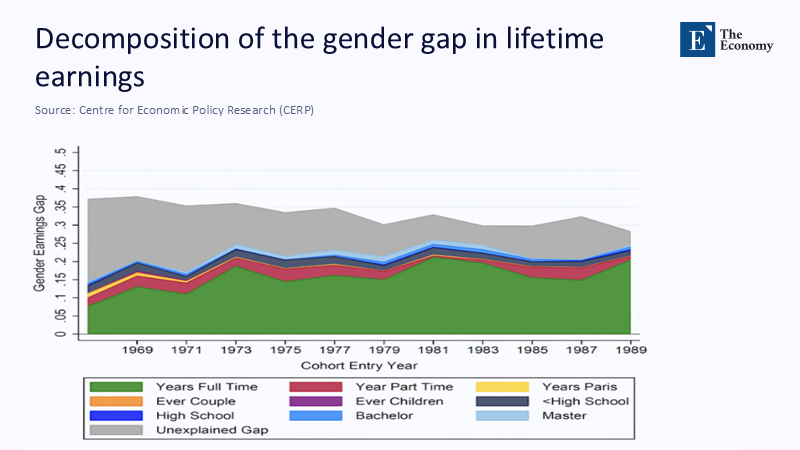

The gap algebra is even clearer when decomposed. Three elasticities—hourly pay, annual hours, and uninterrupted tenure—drive lifetime earnings. French women already earn 94% of male wages in identical occupational codes. Still, they forfeit fourteen percentage points via shorter schedules and another nine through career breaks that accrue compound interest over decades.

If half of the female part-timers magically became full-time without hurting participation, simulations suggest the lifetime gap would shrink by 22%. However, once the empirically observed participation losses are factored in, that improvement melts to barely seven. The arithmetic win is erased by behavioral retreat. Policymakers chasing the mirage of uniform hours underestimate the double-edged elasticity of hours and participation.

Flexibility as Dividend, Not Concession: The Productivity Evidence

The stereotype of part-time labor as a drag on productivity crumbles under scrutiny. A 2023 IESE study covering 12,000 European firms found that voluntary part-time policies boost output per hour by just over two percentage points, primarily due to lower absenteeism and higher retention of experienced staff. Part-time schedules act as a retention subsidy, preserving expensive human capital that would otherwise be lost. Banque de France researchers reach a similar conclusion, noting that wage-setting premia within firms correlates positively with flexible scheduling. In advanced service economies—now 79% of French GDP—marginal output is linked less to sheer hours than task completion, client continuity, and institutional memory. Eliminate flexibility, and employers will hire fewer women with valuable experience, not more.

Cost Structures, Incentives, and the Risk of Shadow Discrimination

Part-time jobs persist because they allow firms to smooth labor costs against demand volatility. The Economic Policy Institute pegs the median wage penalty for part-time status in advanced economies at 19.8%; France’s stand-alone figure—about eleven—still materially lowers average labor cost. Mandating full-time would erase that discount and tempt employers to substitute away from potentially “hours-risky” applicants—a euphemism for women in childbearing years. What looks like fairness in law risks becoming exclusion in practice. Rather than criminalizing reduced schedules, the smarter policy would narrow the cost spread through progressive social-security contributions that shrink—without eliminating—employer arbitrage opportunities.

Care Infrastructure: The Hidden Ledger Behind Labour Statistics

Each data point labeled “part-time” conceals an unpaid care corollary. Despite generous cash transfers, France still lacks roughly 110,000 crèche places. Businesscoot valuations imply that closing the childcare gap would cost scarcely €1 billion—small change compared to the €15 billion already spent on early-years welfare—and would self-finance through payroll tax gains at a 70% rate within three fiscal years. Empirical work from Aix-Marseille shows that each extra childcare slot frees an estimated 28 maternal hours a week; converting even half of those into paid work eclipses any plausible gains from coercive hours mandates. In short, investing in care infrastructure not only addresses the gender pay gap but also buys back women’s time without pushing them out of the workforce.

Comparative Optics: The Dutch and German Lessons

The Netherlands would top every pay gap ranking if high part-time incidence automatically bred inequality. It does not. Dutch women log some of Europe’s shortest average paid weeks—under thirty hours—but the adjusted pay gap has shrunk to roughly 10%. Institutions do the heavy lifting: pension credits accrue pro rata, employees enjoy a statutory right to request hours changes, and the tax code steers clear of penalising the secondary earner. Germany’s 2019 Brückenteilzeit law offers a complementary mirror. Letting employees downshift temporarily with a guarantee of reinstatement to full-time boosted maternal return-to-work rates by four points within two years, without uprating overall labor costs. These examples show that part-time ubiquity does not cause wage gaps; poorly designed benefits and rigid labor codes do.

The Hybrid Revolution: Commuter Time as Hidden Capacity

The fastest-growing vector of flexibility is not a shorter week but a shorter commute. DARES finds that telework in France leaped from 9% pre-pandemic to 26% in 2023 and has stabilized at 21% in early 2025, with women over-represented among hybrid workers. One day of remote work eliminates roughly 1.4 unpaid hours of commuting and transit tasks—time that can be cashed in for paid output or family logistics. A Dutch-style right to request remote work, combined with an offset for home-office costs, would let women claw back hours with no productivity loss. Hybrid models also align neatly with the service-heavy structure of the French economy, where deliverables hinge on deliverables rather than factory floor presence.

A Three-Pillar Blueprint: Aligning Employer and Social Incentives

A reform agenda grounded in behavioral realism must pivot from coercion to calibrated nudges.

First, tapered payroll charges: Levy lowers social-security rates on the first twenty paid hours and gradually increases them so that a 25-hour contract is only marginally cheaper, closing the current 11-point wage gap without outlawing part-time status.

Second, portable training credits: top-up Compte Personnel de Formation accounts for part-timers, so skill acquisition and wage growth proceed on a pro-rated but equalized footing. Experience shows that women in compressed schedules rarely access employer-funded upskilling; a state-sponsored kicker would fix the pipeline without dictating hours.

Third, hybrid-work tax credits offer firms a time-limited deduction when they convert voluntary part-time posts into remote-friendly contracts that maintain full benefit accrual. Qualification would require verifiable logs of remote days, circumventing abuse while amplifying the care-compatibility dividend.

Paternity Leave: Completing the Flexibility Circuit

No discussion of hours and participation is complete without mentioning the other half of the caregiving equation. France expanded paid paternity leave to 28 days in 2021, yet uptake remains below two-thirds of eligible fathers. A Norwegian-style “use-it-or-lose-it” quota tied to pension credits could nudge male uptake higher and rebalance unpaid care. When men return from the labor market, the negative participation elasticity that penalizes women shrinks. Labor-market studies consistently show that each additional week of leave taken by fathers correlates with a 2-per-cent reduction in maternal part-time probability two years later. Equality is also a story of leveling down male hours at life-cycle pinch-points rather than only leveling up female hours.

The Digital Economy and Future of Hours

In the long term, the structure of work itself will be mutating. Platform economies, fractional consulting, and AI-enabled task markets blur the boundary between full-time and part-time. France’s portage salarial already hosts over 120,000 professionals who bill episodically yet accrue full benefits through umbrella companies. Rather than dismantle this intermediate space, policymakers should incorporate it. Mandating real-time hours reporting into the URSSAF system would permit accurate pension accrual without forcing a rigid 35-hour template. Such granular tracking dovetails with a shrinking industrial base and a growing knowledge sector where productivity is lumpy and project-driven. The gender gap debate must, therefore, anticipate a future where time itself is a less reliable proxy for output, strengthening the argument for flexible hours.

Reframing the Optic—Close the Gap by Expanding Choice

France stands at a crossroads. Policymakers can attempt to engineer parity by fiat—outlawing reduced schedules and hoping women adjust—or they can treat flexibility as an asset, fixing the incentive landscape so that part-time no longer entails lifelong penalties. The empirical record converges on a single truth: time is the currency in which women pay for inadequate care infrastructure and rigid work templates. Forcing them to mint more of that currency will not enrich them if the mint’s machinery ejects them entirely. The more brilliant play is to redesign the mint itself. Recognize part-time and hybrid modalities as integral fixtures of modern labor markets, align employer incentives with social goals, and fortify the public goods—childcare, broadband, portable pensions, and father-specific leave—that allow reduced hours to coexist with robust career trajectories.

Close the wage gap by widening choice, not rationing it, and the hourglass will narrow organically without shattering. That—not a blunt cap on reduced schedules—is how France can translate statistical insight into sustainable parity and, ultimately, into a more resilient, inclusive labor economy for the twenty-first century.

The original article was authored by Bertrand Garbinti, a Senior Researcher at CREST - ENSAE, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Part-time work slows the narrowing of France’s lifetime gender earnings gap," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

AspiringToInclude. (n.d.). Why do more women have part-time jobs? Retrieved 24 June 2025.

Banque de France. (2025). The unequal impact of firms on the gender wage gap.

Businesscoot. (2024). The childcare market – France.

CBS. (2025). Gender pay gap is narrowing.

DARES. (2024). Comment évolue la pratique du télétravail depuis la crise sanitaire ?

DARES. (2025). Télétravail et présentiel : le travail hybride, une pratique désormais ancrée.

Economic Policy Institute. (2019). Part-time workers pay a big-time penalty.

Eurostat. (2024). Part-time and full-time employment – Statistics Explained.

IESE Insight. (2023). Part-time work has a positive impact on productivity.

INSEE. (2021). Family, firms and the gender wage gap in France.

OECD. (2025). Gender wage gap (indicator).

The Times. (2025). The Netherlands has gone part-time. Is it working?

VoxEU. (2025). Part-time work slows the narrowing of France’s lifetime gender earnings gap.