Bandwidth over Brownstones: Remote Work and the Coming Inversion of US Wealth Inequality

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

The rise of remote work is not just a trend but a significant shift in the economic landscape. It is quietly rewriting the algebra of American wealth. As employers realize the potential of hybrid timetables, the once robust urban‐land premium that supported middle-class balance sheets is dissolving. By 2030, this erosion is expected to create a deeper fault line in the distribution of household net worth than any current tax change.

The excellent dispersion: how far the home office has traveled

At first glance, the revolution looks incremental—yet “about 29% of paid days in March 2025 were worked from home,” the latest release of the Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes (SWAA) reports, compared with barely 5% before the pandemic. Because every percentage point translates into millions of employee days no longer tethered to a CBD commute, the spatial catchment area of each labor market has exploded: an eighty-minute drive that was once disqualifying becomes acceptable when tolerated only twice a week. This elasticity breaks the monocentric logic that awarded top-tier rents to addresses within a subway stop of the financial district. The same data series shows employer plans settling near 2.3 days of weekly homework—evidence that the shift is structural, not a passing concession to safety protocols.

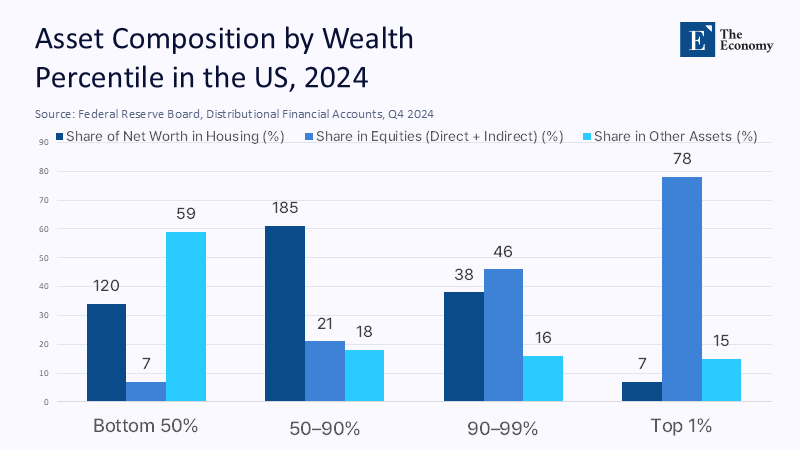

Why housing still matters more than stocks, especially in the middle

Macro balance-sheet arithmetic confirms the stakes. Real-estate assets constitute roughly sixty cents of every net-worth dollar in US household, which holds between the 50th and 90th wealth percentiles. In contrast, the top 1% keep barely seven cents in housing and park the rest in diversified financial portfolios. Federal Reserve flow-of-funds tables show that in 2024 Q4, stock valuations added $300 billion to household wealth even as residential real estate shed $400 billion, leaving the aggregate net worth at a record $169.4 trillion thanks to equity concentration at the summit. If downtown condominiums and brownstones surrender merely 15% of their pandemic gains—a haircut already realized in San Francisco and Seattle since 2022—median families lose roughly 9% of total wealth while the affluent lose less than two. No stimulus cheque can offset that asymmetry.

The crumbling rent gradient: evidence of a stealth price correction

Nationwide asking rents are already down 1.7% year-on-year, with the steepest discounts logged in high-density zip codes. Chandan Economics counts four million rental households headed by full-time remote workers in 2023, a 20% drop from the 2021 peak. Zillow’s panel shows the national average rent flat at $2,100 but slipping in the priciest central tracts even as build-to-rent supply surges in peripheral counties. The mechanics are textbook: telework inflates the “effective” housing supply by allowing workers to substitute distance for the price, so the marginal bid for a downtown lease slides, and the capitalized value of those expected cash flows falls one-for-one.

Inflation’s shelter channel—why cheaper downtown flats check CPI and replay through wealth

Shelter commands roughly a third of the Consumer Price Index basket, and its weight rises under the new 2025 relative-importance matrix. Every notch of disinflation that originates in soft urban rents trims owners’ equivalent rent, pulling headline CPI lower than it would otherwise be. Because monetary policy leans heavily on core inflation prints, cheaper apartments indirectly keep interest rates lower, a feedback that props up equities while muting nominal house-price growth. The result accelerates asset-mix divergence: remote-induced rent disinflation favors those who hold stocks over bricks.

Generations at an inflection point: Boomers’ home-equity bet meets Millennials’ index-fund habit

The Federal Reserve’s Distributional Financial Accounts show that Millennials and Gen Z allocate only about 23% of their assets to housing, in stark contrast to Baby Boomers, who had over 40% in home equity at the same age. At the same time, automatic 401(k) enrollment funnels younger workers into low-cost index funds—risk assets that still enjoy a historical 7% real return. If urban home prices shift from a twentieth-century norm of 4% annual appreciation to a post-WFH glide path of 2%, the crossover point at which equities outperform housing compresses to under a decade. The Wall Street Journal already records a widening ownership gap as high mortgage rates freeze would-be first-time buyers out of metropolitan markets. Yet paradoxically, that exile may shield them from the capital-loss cycle about to hit aging homeowners whose wealth is tied up in a suddenly devalued zip code.

Geography of the remote dividend: uneven shock absorbers across the Atlantic

Cross-country work-from-home patterns imply diverging real-estate futures. An IMF panel of central US, U.K., Danish, and French metros finds that remote work flattened the commercial rent gradient by up to 44% in New York City, Paris, and Copenhagen. Ibercenter, a Spanish coworking operator, reports that suburban office take-up in Madrid has been at its highest since 2015 as firms trade fixed leases for flex space. London offers a counter-narrative: return-to-office edicts from blue-chip employers have revived demand for pieds-à-terre, nudging prime-central prices off their 2024 lows even as vacancy rises in outer boroughs. Financial Times surveys of estate agents show a spike in studio-flat inquiries by commuters facing three-day-a-week mandates. That diversity highlights a policy variable: jurisdictions with elastic zoning and ample green-field supply will transmit telework into price drops more brutally than land-constrained, tax-heavy regimes that can soak demand shifts through densification fees.

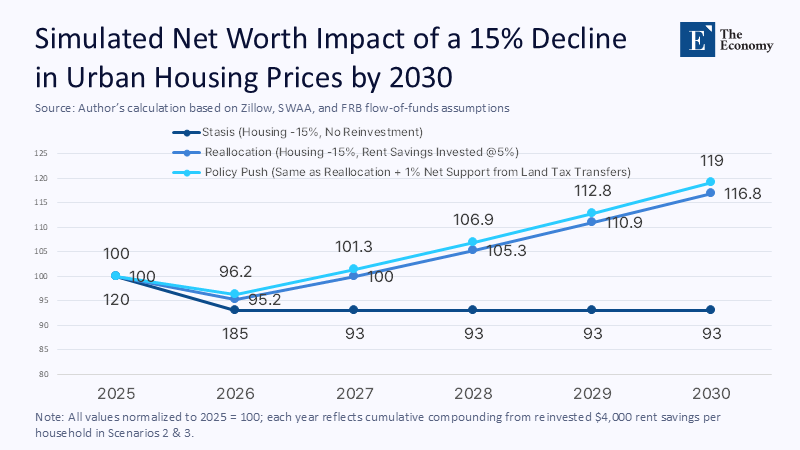

Running the tape to 2030: three scenarios and a sensitivity test

Take a baseline in which remote work plateaus at 35% of paid days by 2030—only six points above today’s reading, but still a quantum leap from 2019. Assume inner-metro rents fall another 10% in real terms, feeding a 15% nominal slide in home values through standard price elasticities. Middle-quintile households, 60% in housing, give up nine net worth points. Now run two variants. In “Reallocation,” half of those households plow their $4,000 a year rent savings into S&P 500 index funds: at a 5% real return, the capital accumulation fully offsets the equity leak in six years, narrowing the net-worth Gini by nearly two percentage points. In “Stasis,” the savings go to consumption; wealth gaps widen because the one-percenters enjoy equity beta. Finally, in “Policy Push,” municipalities layer a land-value tax that recovers part of the windfall from zoning reform and finances broadband build-out in ex-urban counties; the net effect is a modest redistribution of capital gains toward newcomers while encouraging employers to hire nationwide. Even the pessimistic case diverges sharply from the CEPR snapshot of 2022, which recorded only marginal inequality changes because those data froze the frame before the rent gradient truly bent.

Policy architecture for the remote age

The potential for policy reforms to mitigate the impact of remote work on wealth distribution and housing markets is significant. By implementing strategic measures, we can shape a future where the benefits of remote work are equitably distributed, and housing markets remain stable. If the thesis holds, pro-equality frameworks must shift from subsidizing urban ownership to smoothing geographic mobility and asset rebalancing. First, phase out the mortgage-interest deduction and replace it with a capped, revenue-neutral land-value levy; the base is immobile, the incidence progressive, and the incentive neutral to indebtedness. Second, federal infrastructure grants should be redirected from light-rail extensions into last-mile fiber: latency, not lane-miles, is the new commute. Third, mandate default equity contributions on every payroll platform like Australia’s superannuation system does; that move alone could triple stock exposure for the 50th–70th wealth percentiles within a decade. Finally, modernize measurement. The triennial Survey of Consumer Finances is too slow; quarterly micro-linked flow-of-funds tables combined with anonymized mortgage records would allow real-time monitoring of whether remote-work-driven price adjustments compress the distribution or shuffle assets among classes.

Wealth inequality’s next chapter will be written in square footage

A deceptively simple identity governs the post-pandemic economy: fewer days in the office equals less willingness to pay for proximity. When proximity stops commanding a premium, the capitalized value of urban land falls, taxing the cohort whose life savings are embedded in that concrete. Equity-rich households scarcely feel the scrape; equity-poor, house-heavy households do. By clinging to 2022 survey results, we risk misreading a slow-burn earthquake already rumbling through appraisal models and rent negotiations. The policy stakes are enormous. Ignore the dispersion, and the country will drift into a new barbell society of rentiers and perpetual tenants. Lean into it—via land taxes, fiber optics, and portable retirement savings—and the remote-work era could deliver the most significant egalitarian dividend since the G.I. Bill. The clock to 2030 is ticking, measuring not just hours worked at home but the speed at which an old wealth machine—urban housing—gives way to a new one built on bandwidth, diversification, and geographic choice.

The original article was authored by Moritz Kuhn and José-Víctor Ríos-Rull. The English version of the article, titled "US wealth inequality in 2022: A modest reversal at the top, persistent challenges below," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., Buckman, S., & Davis, S. J. (2025). SWAA April 2025 Updates. WFH Research.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025). Consumer Price Index Summary—May 2025.

Chandan Economics. (2025). Remote Work Drop Signals Shift in Rental Market, GlobeSt., 9 April.

Federal Reserve Board. (2025). Distributional Financial Accounts Overview.

Federal Reserve Board. (2025). Financial Accounts of the United States, Q4 2024 (reported in Reuters, 13 March 2025).

Federal Housing Finance Agency. (2025). House Price Index Quarterly Report, Q1 2025.

Financial Times. (2025). Will Return-to-Office Mandates Herald the Comeback of the Pied-à-Terre? 23 April.

Gupta, A., Biljanovska, N., & Dell’Ariccia, G. (2023). Flattening the Curve and the Flight of the Rich: Pandemic-Induced Shifts in US and EuUSpean Housing Markets. IMF Working Paper 23/266.

Ibercenter. (2024). How Has Remote Work Affected the Real Estate Sector?

International Monetary Fund. (2023). Will Working from Home Stick in Developing Economies? IMF Working Paper 23/112.

New York Post. (2025). Buyers Priced Out of Owning Their Dream Home Are Renting Instead, 17 June.

Reuters. (2025). US HousehUSd Wealth Reaches Record $169 Trillion on Stock Gains, 13 March.

Reuters. (2025). Return-to-Office Mandates Fuel Hopes of London Property-Market Revival, 13 June.

Richter, W. (2024). The Most Splendid Housing Bubbles in America, April 2024 Update. Wolf Street.

Wall Street Journal. (2024). Young Americans Are Getting Left Behind by Rising Home Prices, Higher Stocks, 14 December.

Zillow Research. (2025). United States Rental Market Trends, updated 21 June; CPI Shelter Forecast, May 2025.