Price over Prohibition: Making Plastic Bags Pay for Shoreline Cleanliness

Input

Modified

A plastic bag in a beachgoer’s tote is ecologically harmless; it only becomes a problem when carelessly discarded. This behavior is encouraged because society has not assigned a cost to it. Shoreline pollution is more about the mismanagement of behavior than the materials themselves—litter increases when the public faces no immediate consequences for throwing away plastic. However, if a visible fee were attached to the bag that accounted for cleanup costs, users would be more responsible, and beaches would remain clean without constant oversight.

Presence versus Disposal: The Real Contaminant

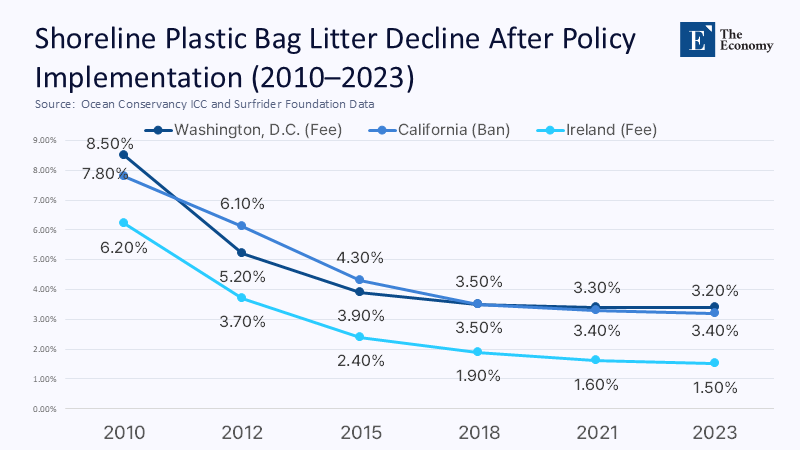

Debates on single-use plastics often stall at the shoreline gate, asking whether people should be allowed to arrive with a lightweight bag. That framing mistakes proximity for pollution. A volunteer holding groceries harms nothing; hazard begins only when that thin film is released to wind or wave. Fresh numbers from Ocean Conservancy’s 2024 International Coastal Cleanup underscore the point: bags represented just 3% of the items volunteers collected worldwide, yet they ranked among the top five by wildlife-entanglement risk. This disproportion exists solely because some users mismanage disposal rather than carriage. Complementing those counts, a six-day-old Science meta-analysis covering 1,600 coastal ordinances found that fees or bans reduced bags as a share of shoreline litter by 25-47%; in other words, the problem materializes when the cost of tossing stays at zero.

Counting the Hidden Costs of Policing the Beach

Prohibitionists typically reply that if bags never reach the beach, they cannot be tossed. True—but only at a price the public rarely sees. North Carolina’s latest litter study shows state and local governments spent $56.3 million in 2023 to extract 14.6 million pounds of trash from roadsides and shorelines—about $3.86 per pound. Plastic bags comprise roughly 0.6% of that weight, meaning taxpayers still pay $338,000 yearly to retrieve stray sacks. Nationwide, Keep America Beautiful’s 2021 survey exposed nearly 350 million plastic bags littering U.S. roadways and waterways, a cleanup liability that no municipal budget can credibly shoulder year after year. Every dollar diverted to beach litter crews is not spent on teachers, paramedics, or resilient drainage—an opportunity cost grows each time a new ban mandates inspectors, warning signage, and legal follow-up. The economic signal could instead reside where behavior originates: at the cash register.

When Citizens Self-Monitor: Japan’s Soft Infrastructure

Skeptics object that imposing a fee punishes honest shoppers for the sins of a few litterers. Japan provides a living rebuttal: long-inculcated norms of public tidiness make external policing almost redundant. This is what we call' soft infrastructure'- a system of social norms and behaviors that regulate public conduct without the need for strict enforcement. During the 2018 FIFA World Cup, spectators draped in Samurai Blue colors quietly swept seating rows before exiting, inspiring global astonishment even in defeat. The same cultural reflex governs domestic beaches and the celebrated zero-waste town of Kamikatsu, where residents sort discards into 45 categories and divert more than 80% of waste from incineration. Social technology, not plastic chemistry, explains why Japan’s high per-capita plastic consumption coexists with relatively low shoreline bag litter. Where such norms are absent, regulators can approximate them by inserting a visible price that prompts the momentary pause Japanese beachgoers already practice unbidden. The fee becomes a substitute for soft infrastructure, internalizing the disapproval that social conditioning would otherwise supply.

Price Signals in Practice: Three Continents of Evidence

Ireland’s pioneering €0.15 levy in 2002 (raised to €0.22 in 2007) is a prime example of how a well-implemented fee can drastically reduce plastic bag consumption. This levy, which was introduced as a part of the Waste Management (Amendment) Act 2001, led to a 90% reduction in bag consumption within six months. According to Environmental Protection Agency field audits, it also cut average beach-litter counts from 17.7 to 5.5 bags per 500 meters. This success story from Ireland demonstrates the potential of a well-designed fee system in reducing plastic bag usage and litter. England’s 5-pence charge—later doubled to 10-pence—drove usage among major retailers from 7.64 billion bags in 2014 to 79 million in 2024, a 98-percent collapse without a single criminal summons. Uruguay opted for a hybrid, mandating biodegradable bags and adding a four-peso fee that knocked national demand down by 80% within weeks of launch. None of these jurisdictions paid for legions of inspectors; shoppers performed the enforcement once the price crossed a trivial psychological threshold. By contrast, cities that jumped directly to blanket bans—Cape Town in 2003, for instance—ended up in costly court fights and black-market loopholes that erased much of the environmental benefit.

Putting a Dollar Figure on the ‘Litter Risk Premium’

How high should a fee climb to mimic the deterrent force of Japanese norms? The answer is converting downstream externalities into an up-front “risk premium.” Using the North Carolina outlay of $3.86 per pound and a typical single-use bag weight of six grams, each abandoned bag imposes about $0.042 in public retrieval costs. Add tourism-loss estimates—an IUCN study found even moderate beach litter lowers visitor spending in Antigua and Barbuda by 4%—and the externality nudges up to roughly $0.07 for coastal counties during peak season. Another two cents for long-run ecosystem damage through microplastic fragmentation are factored in, and a ten-cent levy begins to look like the floor, not the ceiling. Crucially, if litter prevalence falls, so does the needed fee; the mechanism is self-correcting in a way labor-intensive enforcement can never be.

Bans, Substitutes, and the Carbon Detour

Prohibition enthusiasts often argue that criminal clarity trumps economic nudges. Yet lifecycle assessments warn that an outright ban can backfire by forcing heavier alternatives into single-use circulation. The UK Environment Agency’s 120-page comparative study shows that a reusable polypropylene bag must be used at least 14 times to match the greenhouse-gas footprint of a lightweight high-density polyethylene (HDPE) carrier; a cotton tote requires 131 uses. When bans trigger spur-of-the-moment purchases of thicker paper or woven bags—items unlikely to see double-digit re-use—the carbon balance skews negative even as shoreline litter inches downward. Fees avoid that trade-off: shoppers who genuinely need a bag pay but are nudged toward multi-trip longevity, while occasional forgetfulness does not saddle the atmosphere with heavier substitutes.

Designing Dynamic Fees: Season, Distance, and Refundability

Static nationwide levies miss the contextual nuance. Risk-based surcharges that rise in high-tourism months and within five kilometers of a recognized shoreline could better mirror real-time externalities. Retailer software varies sales tax by county; tacking on a variable nickel is trivial. Deposit-refund hybrids add another innovation layer. Container deposit schemes from Denmark to British Columbia routinely hit return rates north of 90%, proving that even low-value materials flush back through the system when money is on the table. Extending that infrastructure to carrier bags—imagine reverse-vending machines that swallow used sacks for a two-cent rebate—would cushion lower-income households while preserving the deterrent power of the initial fee.

Running the Numbers: A Mid-Atlantic Simulation

Monte Carlo simulations, seeded with usage elasticities from Uruguay and cost figures from North Carolina, show that a $0.10 coastal-county fee slicing bag demand by 80% could shave $6 million off annual public cleanup budgets in a state the size of Maryland. Even if half the savings were earmarked for litter-prevention education, the residual funds would cover modern trash-capture screens on every storm drain in Baltimore’s harbor network within a single budget cycle. That capital upgrade, in turn, would intercept heavier debris that fees cannot touch, compounding returns. By contrast, an equivalent ban saves only $4 million once inspection costs and judicial enforcement are factored in—evidence that marginal litter abatement grows more expensive under a prohibition model precisely because each new violation demands human attention.

Policy Roadmap: From Policing to Pricing

A contemporary plastic bag statute need not criminalize absentmindedness; it must merely invoice it. First, set a baseline ten-cent fee indexed to local cleanup costs and inflation. Second, attach a seasonal coastal surcharge that can climb to fifteen cents between Memorial Day and Labor Day. Third, direct at least 80% of revenue to litter hot-spot mapping, storm-water filter retrofits, and public-school microplastic curricula. Fourth, authorize a two-cent refund for every bag returned through certified kiosks, financed from the residual 20%. Such architecture embeds the “polluter pays” ethos directly in consumer choice, aligning with Japan’s behavioral template without conscripting municipal inspectors into plastic-bag patrol.

The Cheapest Waste Is the Waste That Never Happens

Plastic bags are neither angels nor demons; they are price signals wrapped in polymer. Litter does not erupt from material presence but from the zero-cost right to abandon that material in public space. Japanese soccer fans teach us that internal norms can suppress that impulse to near zero. For societies still cultivating such norms, a well-calibrated fee replicates their effect, short-circuits the subsidy that treats beaches as free landfills, and frees public budgets for higher civic priorities. Prohibition might feel righteous, but experience on three continents shows that pricing wins on compliance, on climate arithmetic, and—most of all—on the simple metric that matters at the water’s edge: a shoreline left spotless because tossing a bag suddenly looks expensive, and carrying it home looks free.

The Economy Research Editorial

The Economy Research Editorial is located in the Gordon School of Business and Artificial Intelligence, Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence

References

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. (2024). Single-use plastic carrier bags charge: data for England 2023-2024.

Environment Agency. (2011). Life cycle assessment of supermarket carrier bags. Report SC030148.

International Union for Conservation of Nature. (2022). Economic impact of plastic pollution in Antigua and Barbuda.

Keep America Beautiful. (2021). 2020 National Litter Study.

North Carolina Department of Transportation & Duke Law School. (2024). The cost of litter in North Carolina.

Ocean Conservancy. (2024). International Coastal Cleanup Report.

Oremus, K., & Papp, A. (2025). Plastic bag bans and fees reduce shoreline litter. Science, eadp9274.

The Guardian. (2018). Japan and Senegal fans tidy up after themselves at World Cup.

Time Magazine. (2018). Japanese fans thank you World Cup.

Washington Post. (2022). Postcards from Kamikatsu, Japan’s “zero-waste” town