When AI Empowers Democracy: Lessons from Thailand’s Transparency Play and the Philippines’ Disinformation Spiral

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

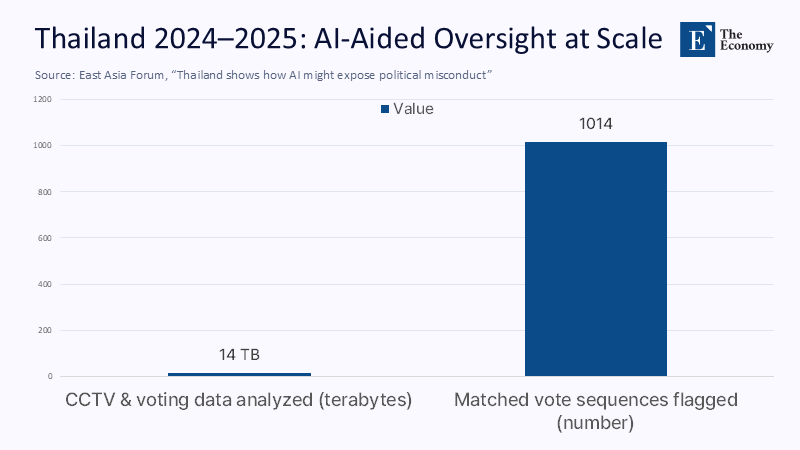

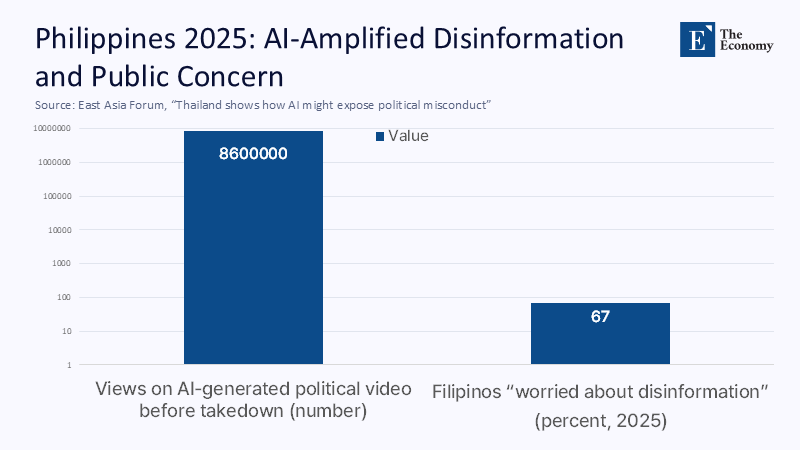

Thailand’s investigators fed more than 14 terabytes of CCTV and voting data from the 2024 Senate races into AI systems. They surfaced 1,014 suspiciously identical ballot selections—anomalies a human team would likely have missed on deadline. In the same fortnight that Thai authorities used algorithms to probe potential collusion, a Philippine senator shared an AI-generated propaganda video that drew 8.6 million views before takedown. At the same time, 67% of Filipinos told researchers they were more worried about disinformation than ever. The contrast is not accidental. It is institutional. Where a justice ministry’s investigators paired AI with statisticians and legal oversight to map misconduct, rival political camps in Manila deployed generative tools to flood feeds and harass victims’ families after a former president’s arrest. The lesson for education is blunt: the technology is combustible either way, so the curricular and professional “fire codes” we build now—AI literacy, civic forensics, and public-interest data practice—will determine whether democratic trust is rebuilt or torched.

Reframing the Debate: From “AI = Disinformation” to “AI = Institutional Choice”

Transparency is key in the use of AI. Thailand’s Department of Special Investigation (DSI) serves as a prime example. With the aid of external experts and clear investigatory aims, DSI used AI to analyze footage, correlate movements, and flag improbable patterns in ballot markings—finding duplicated vote sequences across lists that would be vanishingly unlikely by chance. The result is not a utopian vision of technology, but rather due process with more horsepower, publicly communicated. By contrast, in the Philippines, generative tools became accelerants: political surrogates used AI content to distort evidence, normalize deepfakes, and push coordinated talking points, some produced by a marketing firm now flagged in an AI-safety report: same tools, opposite governance choices, opposite civic outcomes.

In this new perspective, schools and universities are not mere spectators. They are the primary system entrusted with nurturing the judgment, methods, and norms that graduates will carry into civil service, journalism, and politics. The cumulative effect is significant: as trust in institutions wavers—government trust globally hovers near the low-50s, and media similarly—the question is not whether AI will be part of civic life, but whether graduates can wield it for verification rather than virality. Therefore, education policy must shift from generic “media literacy” modules to practical civic audit literacy: teaching students how to design, validate, and publicly explain AI-assisted oversight so communities can see not just claims, but evidence trails.

What the Numbers Say—And How We Estimated What They Don’t

Start with Thailand. Public reporting indicates investigators processed 14 TB of CCTV and voting data and flagged 1,014 matched votes across two lists—an indicator of coordinated behavior. Suppose, conservatively, those lists contained 10,000 votes. A cluster of 1,014 near-identical selections would be orders of magnitude above random expectation. Even if the base lists were twice that size, the anomaly remains glaring. This is not proof of guilt; it is a quantitative red flag that justifies targeted interviews, chain-of-custody checks, and judicial review. Our inference method here is transparent: we triangulate reported totals with minimal assumptions about denominator size and avoid overclaiming beyond what the data support. The key is not the exact ratio; it is the public visibility of the analytic path from footage to finding, which citizens can assess.

Now consider the Philippines. In March–July 2025, after the International Criminal Court arrested former President Rodrigo Duterte, Reuters and Al Jazeera documented a surge of AI-generated videos targeting victims’ families and critics, along with coordinated campaigns that leveraged fake accounts. An AI-safety report linked a local firm to bulk comment generation and trend analysis, while platform data and fact-checking coalitions tracked elevated deepfake usage. The informational climate deteriorated: the Reuters Institute’s 2025 report recorded record-high concern about disinformation (roughly two-thirds of respondents in the Philippines), and specific deepfake examples reached millions of views before moderation. These are not minor effects; they shape attention budgets, seed cynicism, and raise the cost of legitimate civic participation. Our method: privilege primary documents (safety reports, official surveys), then buttress with reputable journalism that supplies the vivid particulars citizens encountered.

Why This Matters for Education Now: From Literacy to Audit Literacy

If trust is fraying, it is because many people doubt that anyone competent is minding the evidence. Global surveys show business remains the most trusted institution at around 62%, with government and media lagging in the low 50s—even as grievance and “hostile activism” rise. Education systems can’t repair macro-politics, but they can help rebuild epistemic competence where it touches daily life: school board decisions, municipal procurement, campus governance, and student media. Audit literacy means students learn to design verification workflows (chain of custody, sampling frames), operate AI tools with explicit constraints (false favorable policies, confidence thresholds), and communicate findings with humility (what the data say, what they don’t, and how to replicate). That is the DNA of the Thai approach—and the antidote to AI-theater in politics.

The most persuasive reason to move now is practical: the interventions that reduce susceptibility are inexpensive at scale. Cambridge and Google’s Jigsaw ran a real-world prebunking experiment on YouTube, exposing 5.4 million users to 90-second clips about manipulation tactics. Within 24 hours, recognition of those tactics rose by about five percentage points—for roughly US$0.05 per meaningful view. That’s a school district’s poster budget producing measurable inoculation. Pair that with OECD’s Truth Quest work, showing that people who depend on social platforms for news tend to be worse at identifying false content, and the pathway is clear: prebunk in the channels where students already live, then scaffold with classroom practice that translates tactics into transparent checks.

What Implementation Looks Like: Concrete Moves for Educators and Administrators

Teacher education needs to evolve from “spot the fake” worksheets to forensic walkthroughs. A unit might start with a dataset—public expenditure receipts, school transportation logs, or, yes, synthetic ballot images created for training—and a question: what anomalies would justify further inquiry? Students use an AI tool to cluster patterns, but they must document prompts, decision thresholds, and error risks, then produce a narrative memo: what this suggests, what due process requires next. The assessment is as much about method transparency as it is about the output. This trains the civic muscle that separates Thailand’s oversight use from the Philippines’ influence use: not “can you make content,” but “can you make a case.” UNESCO’s guidance on generative AI can anchor policies about age-appropriate use, data protection, and educator validation so schools teach responsibly without opting out of modern tools.

Administrators, meanwhile, should stand up light-weight Public-Interest AI Labs across districts and university systems. Think of them as teaching hospitals for evidence: cross-functional teams of educators, data analysts, student journalists, and community partners that pilot transparent AI workflows on real public questions (transport equity, procurement, campus safety, facilities scheduling). Governance guardrails matter: publish model cards, keep detailed logs, appoint external reviewers, and, crucially, ensure a transparent chain of custody for any sensitive data. APEC’s 2025 anti-corruption technologies study is blunt: tools are not panaceas; they work only inside strong institutions with clarity on process and accountability. Build that muscle locally, and schools become exemplars of trust-building, not just lecturers about it.

Policy Architecture: The Dos and Don’ts Lawmakers Should Codify

Policy must ensure the transparency that makes oversight legitimate. Borrow from Brazil’s recent approach: its electoral authority both warned candidates against weaponizing AI and set formal resolutions that restrict deceptive uses during campaigns—demonstrating that clear, enforceable rules can deter abuse before it scales. In parallel, the Estonian parliament’s training and deployment of AI for legislative support—anchored in public data and documented processes—shows how to operationalize trustworthy AI in daily governance, not just in emergencies. The template for education policy is similar: define permissible classroom and administrative uses, require public model documentation for school-procured systems, and make incident reporting mandatory when AI outputs are used in high-stakes decisions.

Curriculum standards should be updated in two directions at once. First, incorporate algorithmic accountability into media and information literacy: students should learn how recommender systems and text generators shape attention and error. Second, adopt a prebunking mandate: every secondary student should receive short, repeatable inoculation modules each term, delivered across the classroom, library, and student media channels—and mirrored in parent communications. OECD’s guidance underscores that media literacy must sit within a broader digital literacy strategy that addresses how platforms and AI work. Tie funding to implementation fidelity, require public reporting on reach and effect, and invite independent researchers to A/B test improvements. This is how you turn an abstract “AI literacy” goal into measurable trust gains.

Anticipating—and Answering—the Hard Critiques

Critique one: AI-assisted oversight is surveillance by another name. The answer is scope, consent, and proportionality. Thailand’s example is not permanent blanket monitoring; it is targeted analysis of election-facility footage with concrete chain-of-custody and legal supervision, followed by public explanation of anomalies and next steps. In education contexts, the analog is clear: no covert student monitoring; documented, time-bound projects with IRB-style review; and deletion schedules that match purpose. The standard is not “trust us,” but “verify us.” Institutions that publish their methods—inputs, thresholds, independent checks—will win the benefit of the doubt that generic privacy assurances never earn.

Critique two: Prebunking is a soft pedagogy that barely moves the needle. The empirical record says otherwise. In a field experiment reaching millions, prebunking lifted recognition by about 5 points in a noisy environment, at costs any district can afford. That’s not the last mile, but it’s a measurable first mile that scales. Pair it with project-based audit literacy and with platform-agnostic truth-tests drawn from the OECD Truth Quest metrics, and the cumulative effect compounds. Critique three: Tech evolves too fast for policy. True—so write process rules, not brittle lists. Require transparent logs, external audits, and rapid takedown protocols; set procurement requirements for model documentation and data protection; and mandate quarterly public briefings on incidents and improvements. Institutions don’t need omniscience; they need competence and candor.

Trust by Design, Not by Accident

The opening contrast still stands: in Bangkok, AI helped investigators see the civic record more clearly; in Manila, AI was used to smear it. If education wants to matter in that forked road, it must stop treating AI as a vocabulary word and start using it as an object lesson in method. Build audit literacy into the curriculum. Stand up public-interest AI labs with published model cards, logs, and external review. Prebunk at scale where students live online, then rehearse the verification steps in class until they’re muscle memory. And legislate transparency as a process: chain-of-custody, thresholds, appeals, and deletion. If we normalize those habits—explainable prompts, checkable inferences, open evidence—students will graduate into citizens who expect the same of their parties, parliaments, and platforms. That is how a region long typecast as a cautionary tale for digital politics can become a working demonstration of “AI for accountability.” The choice is not the tool. It’s the posture. Choose legibility. Choose trust.

The original article was authored by Dr Pattharapong Rattanasevee, a lecturer at the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Mahidol University, Thailand. The English version, titled "Thailand shows how AI might expose political misconduct," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Al Jazeera. (2025, July 15). AI and disinformation fuel political tensions in the Philippines.

APEC Policy Support Unit. (2025, June). Technologies for preventing, detecting, and combating corruption (PSU report).

Cambridge University. (2022). Social media experiment reveals potential to “inoculate” millions of users against misinformation.

Edelman. (2025). 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report.

Estonian Parliament (Riigikogu) & IPU. (2025, April 16). The Estonian Parliament trains MPs and staff in using AI tools.

Nortal. (2024, October 16). How AI accelerates the legislative power of the Parliament of Estonia.

OECD. (2024, June 28). The OECD Truth Quest Survey: Methodology and findings.

OECD. (2024, March 4). Facts not fakes: Tackling disinformation, strengthening information integrity.

OpenAI. (2025, June 5). Disrupting malicious uses of AI: June 2025

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. (2025, June 17). Digital News Report 2025 (Philippines country profile and executive summary).

Reuters. (2025, February 29). Brazil justice warns candidates not to use AI against opponents.

UNESCO. (2023, updated 2025). Guidance for generative AI in education and research.

UNESCO. (2025). Artificial intelligence in education (AI competency frameworks overview).

East Asia Forum. (2025, July 31). Thailand shows how AI might expose political misconduct.

Comment