From Emperor to Broker: China’s Tactical Multilateralism Meets a Wary Southeast Asia

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

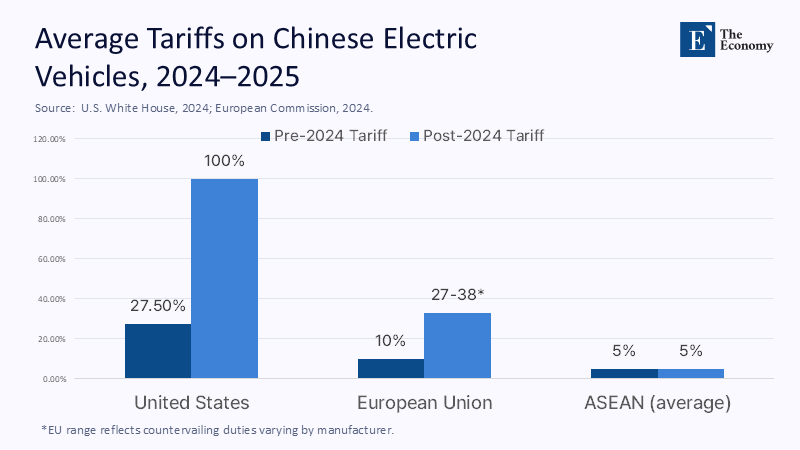

In the first quarter of 2025, ASEAN quietly became China’s largest trading partner yet again, accounting for 16.6% of China’s overall foreign trade—about 1.71 trillion yuan (US$234 billion) in just three months. In 2024, China–ASEAN trade reached roughly 6.99 trillion yuan (US$963 billion). These are not ceremonial figures; they are the plumbing of a shifting order. At the same time, Washington and Brussels have slammed the brakes on Chinese green-tech exports: the United States raised EV tariffs to 100% and hiked duties on batteries, solar cells, and other inputs; the European Union imposed up to ~38% countervailing duties on Chinese battery electric vehicles. Beijing’s response has not been to bang the table, but to build bridges—upgrading the China-ASEAN FTA (“Version 3.0”), nurturing minilateral schemes in the Mekong, and seeding factories from Rayong to Morowali. The question is not whether China is suddenly altruistic; it’s whether this tactical multilateralism is learning to play with the world rather than over it—and whether Southeast Asia can harness it without becoming dependent on it.

Reframing the Claim: From “true multilateralism” to tactical brokerage

Let’s retire the binary. China is not an empire repackaged nor a benign steward of an open commons. It is a broker learning—to its advantage—how to stage multilateral behaviors that reduce tariff exposure, keep supply chains sticky, and stabilize export channels after the United States and European Union hardened their trade defenses. The thrust is visible: conclude and submit ACFTA 3.0 for leader sign-off; deepen the Digital Silk Road with e-commerce cooperation; and widen Lancang-Mekong funds that bundle small, visible public goods with tighter production networks. Brokerage, not benevolence, is the point. For a region that distrusts hegemons but craves financing, standards, and jobs, performative multilateralism can be good enough—if ASEAN’s agency remains intact. The task, then, is not to ask whether China has discovered authentic multilateral virtue. It is to judge whether its new habits and the region’s counter-moves produce net resilience—or a subtler dependence dressed in rules and ribbon cuttings.

What the Numbers Show: ASEAN as a shock absorber and amplifier

The data read like a playbook. ASEAN drew a record US$230 billion of FDI in 2023, the world’s largest share among developing regions, with flows concentrating in digital and green industries. Chinese firms are anchoring capacity where tariffs bite: BYD’s Thailand plant opened in 2024 with 150,000-unit capacity and battery assembly on site; CATL’s nearly US$6 billion battery “integration” project in Indonesia spans mining, materials, and manufacturing. Meanwhile, China–ASEAN trade is rising even as the West derisks: US$234 billion in Q1 2025 alone. Yet there is a darker edge: as Chinese exports pivot toward the Global South, ASEAN manufacturers face import deflation and factory pressure, especially in textiles, electronics, and autos—an emergent “China shock” inside ASEAN. The region, in other words, is both a shock absorber (soaking up supply chain relocation) and amplifier (magnifying China’s upstream dominance). That duality matters for policy: jobs today can become bargaining leverage tomorrow.

Tariffs, Rules of Origin, and the Bypass Temptation

Much of China’s new “multilateral” muscle is really about routing. When the United States raised EV tariffs to 100% and increased tariffs on batteries, semiconductors, and solar cells, and when the EU added up to ~38% on Chinese EVs, the incentive to re-site assembly across ASEAN grew obvious. But the guardrails tightened too. The U.S. Commerce Department has already found circumvention of China's solar duties via Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam, and new anti-dumping/countervailing cases extended scrutiny across Southeast Asia—the result: a compliance race around rules of origin (ROO). Agreements like RCEP and the upgraded ACFTA 3.0 deepen cumulation options that legally re-qualify goods as “regional,” yet the utilization rate of these provisions remains uneven and complex. For educators and administrators, this is a curriculum signal: the next decade’s graduates will need ROO literacy, not just generic “global trade” slides. For policymakers, it’s a standards signal: invest in customs data, digital certificates of origin, and enforcement capacity so legal cumulation doesn’t become illicit relabeling.

Duration and Depth: How long does the pivot last?

Two clocks tick. First, the geopolitical clock: tariff policy in Washington and Brussels is now bipartisan on China. Even with leadership changes, the strategic frame—derisk where you must, decouple where you can’t—is sticky. That means China’s brokerage posture will intensify, not fade, across 2025–2028. Second, the industrial clock: Southeast Asia’s EV, battery, and solar ecosystems are growing but fragile. They import a high share of Chinese intermediates, making them vulnerable to upstream price shocks and downstream tariff swings. ISEAS and the Asia Society identify short-run gains but warn that escalation could offset them if ASEAN doesn’t move up value chains and strengthen local linkages. In this window, ACFTA 3.0 and RCEP can become vehicles for standards harmonization and SME onboarding—or conduits for deeper concentration of Chinese value-added. The outcome depends less on China’s IT factor than on ASEAN’s policy traction: skills, infrastructure, interoperable data regimes, and selective defensive tools when import surges threaten local industry.

Education’s Near-Term Agenda: Build agency, not dependency

Education is where this geoeconomic story gets practical. Start with human capital for ROO and supply-chain compliance: teach the difference between substantial transformation and superficial processing; simulate multi-country bills of materials under RCEP/ACFTA; and bring customs and trade lawyers into capstone clinics. Then tackle GVC analytics: move beyond gross-export tallies to Trade-in-Value-Added (TiVA) and map where Chinese value-added sits in ASEAN’s final demand. Next, redesign industry-embedded programs around live projects with EV, battery, and solar suppliers in Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malaysia. Student mobility can scale this quickly: in 2023, more than 175,000 Chinese-ASEAN students crossed borders, a pool that ministries can channel into joint degrees with required internships in compliance, standards, or testing labs. Finally, build data partnerships with customs and standards agencies—anonymized where needed—so students solve real bottlenecks in certification, e-commerce logistics, and carbon reporting. That is how schools turn geopolitical flux into graduate advantage rather than graduate precarity.

What Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers Should Do

For universities, integrate a three-course spine: (1) Geoeconomics of Tech (tariffs, subsidies, industrial policy), (2) Rules of Origin & Compliance (RCEP/ACFTA case files), and (3) Supply-Chain Data (ERP exports, traceability, carbon footprints). For administrators, pivot exchanges toward skills-bearing mobility—credit-bearing placements in EV and solar ecosystems and trade-law clinics. For ministries of education and trade, co-fund Testing & Certification Hubs with industry to keep value chain steps onshore. Support ROO helpdesks for SMEs so they can legally accumulate inputs without risking U.S./EU penalties. And because the temptation to bypass won’t vanish, pair facilitation with transparent enforcement—digital certificates of origin, randomized audits, and penalties that sting but don’t scare off investment. The prize is not nodding along to China’s choreography; it’s writing regional parts into the score so when Chinese firms “go regional,” ASEAN captures more skill, IP, and negotiating leverage rather than just payrolls and power bills. (Key context: U.S./EU tariff shifts on EVs and solar, BYD and CATL siting choices, and the ACFTA 3.0 rules agenda.)

Anticipating the Critiques—and answering them with evidence

“This is an empire with paperwork.” Not if ASEAN insists on rules with reciprocity. The ACFTA 3.0 text under review covers digital and green economy chapters that, if written with enforceable transparency and supply-chain connectivity standards, can expand regional agency. The presence of EU and U.S. tariffs will continue to discipline relocation games: flat-out transshipment risks heavy penalties; that pushes firms to invest in real local content, training, and testing—a better outcome than pure routing. “Relocation will dry up if Washington tightens again.” Some will, but Chinese producers have already placed physical bets—Rayong and Morowali are sunk costs—while RCEP cumulation reduces friction for legally regionalized content. “Universities can’t move the needle.” They can, by shaping compliance-literate graduates, building shared labs with standards bodies, and curating internships that push suppliers up quality ladders. In short, the answer to power asymmetry is not isolation; it’s institutional competence stitched into enforceable, multilateral—and yes, tactical—rules.

Learning to Play Without Owning the Board

China has not discovered “true multilateralism.” It has been found that acting multilaterally—upgrading FTAs, bankrolling sub-regional funds, colocating factories, and performing openness—works when the world’s biggest markets erect tariff walls. The statistic that matters is not a single headline number, but the ensemble: ASEAN at 16.6% of China’s trade in Q1 2025; nearly US$1 trillion in two-way trade last year; plants and projects that convert paper rules into real payrolls; and tariffs that nudge opportunistic routing toward lawful regional content. This is not a morality play. It is a negotiation about where value is added, who writes the rules, and how quickly skills compound. If Southeast Asia wants to benefit from China’s brokerage without becoming bound by it, education and policy must move together: teach the rules, wire the data, and insist on reciprocity. Let China learn to play with the region; then make sure the syllabus, not the script, sets the terms of the game.

The original article was authored by GU Bin, a PhD student at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. The English version, titled "China’s ‘true multilateralism’ as an alternative to Washington," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2024). An assessment of rules of origin in RCEP and ASEAN+1 free trade agreements.

Asia Society Policy Institute. (2024). Balancing act: Assessing China’s growing economic influence in ASEAN.

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). (2024, Oct.). Joint statement on the substantial conclusion of the ASEAN–China Free Trade Area (ACFTA) 3.0 upgrade negotiations.

Channel NewsAsia. (2024, July 4). China’s BYD opens EV factory in Thailand, first in Southeast Asia.

European Commission. (2024, Dec. 12). EU imposes duties on unfairly subsidised electric vehicles from China (IP/24/5589).

European Commission. (2024, Oct. 4). Commission proposal to impose tariffs on imports of BEVs from China obtains necessary support from EU Member States (STATEMENT/24/5041). Iseas–Yusof Ishak Institute. (2024). The impacts of supply chain reconfiguration on ASEAN economies (ISEAS Perspective 2024/35).

OEC. (2023). ASEAN: Exports, imports, and trade partners.

Reuters. (2025, May 21). China, ASEAN complete negotiations on upgraded free trade deal.

Straits Times. (2025, July 12). China, Asean to submit upgraded free trade deal to leaders in October, says China’s Wang Yi.

U.S. Department of Commerce. (2023, Aug. 18). Final determination of circumvention inquiries of solar cells and modules from China via Southeast Asia.

U.S. White House. (2024, May 14). FACT SHEET: President Biden takes action to protect American workers and businesses from China’s unfair trade practices.

UNCTAD/ASEAN Secretariat. (2024). ASEAN Investment Report 2024.

Xinhua/China.org & China Daily (compiled). (2024–2025). China–ASEAN education cooperation: Student exchanges surpass 175,000 (2023).

Comment