Who Should Pay to Clean the Air? Eco-Taxes, Fairness, and the Future of German Manufacturing

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

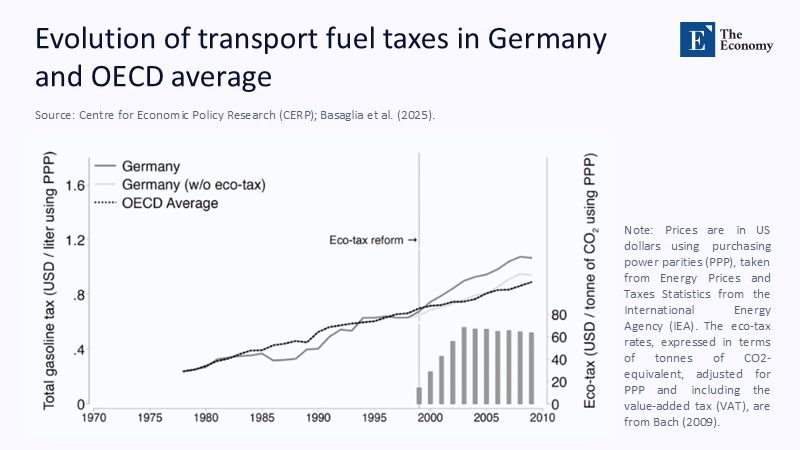

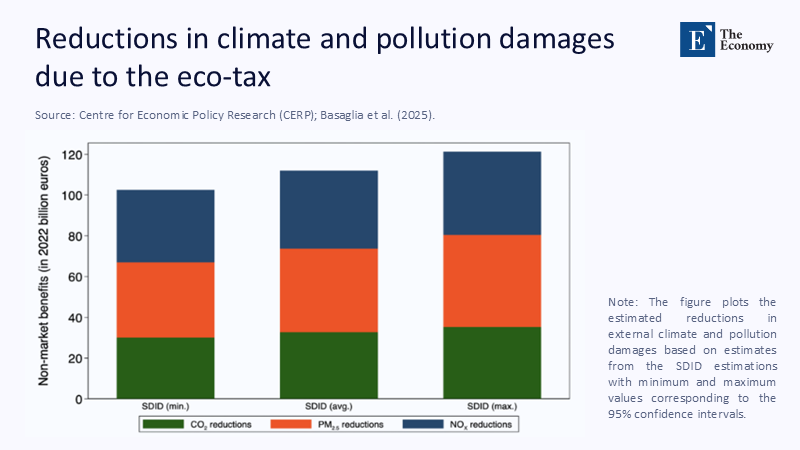

The most uncomfortable number in Europe’s air-quality debate isn’t a carbon price; it’s a body count. In 2022, the European Environment Agency estimated that 239,000 Europeans died early from PM2.5 exposure above WHO guidelines. Those deaths are falling over time, but they remain the region’s most significant environmental health cost. Meanwhile, the IMF puts global fossil-fuel subsidies—mostly the underpricing of local air pollution and climate damages—at $7 trillion in 2022. Zoom in on Germany and a different number snaps into focus: a new 2025 analysis of the country’s 1999 ecological tax reform (ETR) finds more than €100 billion in avoided external damages, roughly two-thirds from cleaner air. Set side by side, these figures tell a simple story. For decades, the “social cost of cleaning” has been shouldered by ordinary households through higher health burdens and general taxation. Eco-taxes flip that logic: polluters—and especially energy-intensive producers—are made to pay their share of the bill. The question isn’t whether this correction erodes industry; it’s whether we design it well enough to keep factories competitive while finally charging the right party for the mess.

Reframing the Bill: From General Taxpayers to Polluters

The standard defense of industry’s historical underpricing is familiar: low energy costs kept products cheap, exports strong, and jobs plentiful. That logic obscures who paid the cleaning bill—health systems, municipal budgets, and families living downwind. Economists have a dry term for this: an implicit subsidy. When fuel is priced without the costs of local air pollution and greenhouse gases, the public makes up the difference in shorter lives, hospital admissions, and tax-funded infrastructure. The IMF’s most recent update quantifies this mispricing globally and finds that nearly 60% of total fossil-fuel “subsidy” value arises from undercharging for global warming and local air pollution, not cash handouts. The practical implication for policy is straightforward: a properly designed fuel or carbon tax removes the subsidy by internalizing those costs in producer and consumer decisions. That is not an “extra burden”; it is the end of an unfair discount.

The German ETR was built around that principle and did something clever with the revenue: it reduced payroll taxes to lower non-wage labor costs. DIW Berlin’s microsimulation shows that ecological-tax proceeds—about €20 billion per year—financed a higher federal grant to the pension scheme, leaving the contribution rate roughly 1.2 percentage points lower and pensions about 1.5% higher than otherwise. This is the right kind of fairness arithmetic: shift the environmental bill onto polluting inputs while recycling the proceeds to ease distortions in labor markets. For households, the distributional picture is mixed (low-income groups can face higher energy burdens absent targeted relief). Still, the overall reform is close to revenue- and burden-neutral once the pension channel is included.

What the Counterfactual Shows: Germany Without the Eco-Tax

The strongest test of the “green death” narrative is empirical: what would have happened without the ETR? A 2025 CESifo working paper uses synthetic difference-in-differences across more than a thousand European regions to construct Germany’s counterfactual. The headline is blunt: the reform drove sizable aggregate reductions exceeding 10% per year in transport-related CO₂ and local air pollutants relative to the synthetic baseline. Using official damage valuations, the authors estimate over €100 billion in avoided external costs since the reform—about two-thirds from health benefits as PM, NOx, and other emissions fell. Benefits are larger in lower-income regions, a crucial equity result because environmental burdens often map onto socioeconomic disadvantage. In other words, the ETR didn’t just cut emissions; it rebalanced who absorbs the harms.

Methodologically, this matters because it goes beyond correlations or modelled scenario runs. Synthetic control constructs a “virtual Germany” out of similar regions that didn’t experience the ETR price signal in the same way, then tracks the divergence. That makes the counterfactual more credible than simple before-and-after comparisons. It also rebuts the idea that air-quality gains were merely a by-product of 'deindustrialization', a process of economic change in which a country or region shifts from an industrial to a post-industrial economy. The estimated effects are persistent and aligned with timing around fuel-tax changes, not just long-term structural decline. As we consider today’s eco-tax expansions and ETS reforms, this is the kind of evidence policymakers should anchor to: real-world externality reductions, monetized with transparent damage values, and geographically disaggregated to test who benefits.

Competitiveness and Leakage: Real Risks, Real Policy Tools

None of this denies Germany’s industrial pain since 2022. Energy prices spiked, foreign demand softened, and trade tensions bit. By June 2025, industrial output had fallen to its lowest level since the pandemic, with a 1.9% month-on-month drop and a quarterly GDP contraction. Export orders sagged, and the automotive complex—long the workhorse of German manufacturing—lost momentum amid tariffs and Chinese competition. It is tempting to blame eco-taxes for a broader malaise, but the data point to multiple concurrent shocks, only some of which are environmental-policy related. That diagnosis matters because it changes the cure: we need competitiveness backstops, not a retreat from internalizing externalities.

On the issue of 'leakage', which refers to the potential for businesses to relocate to areas with less stringent environmental regulations, Europe has moved from hand-wringing to architecture. The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) entered its transitional phase in October 2023 (reporting only) and shifts to full financial adjustments in 2026, mirroring EU carbon costs on imports of carbon-intensive goods. That does not eliminate all leakage pathways—especially for exporters facing third-country competition—but the Commission in July 2025 unveiled plans to mitigate export-related leakage as free allowances phase out. The empirical literature, meanwhile, is nuanced. Some studies find limited or no historical leakage under the EU ETS, while newer work using trade-embedded carbon shows leakage in particular sectors and time windows. The policy takeaway is not to abandon pricing but to pair it with border adjustments, innovation support, and targeted relief during the transition.

Jobs and Prices: What Changes When the Right Sector Pays?

The claim that eco-taxes inevitably destroy jobs ignores the revenue-recycling lever built into most modern designs. Germany’s original ETR used proceeds to lower social-security contributions, and credible evaluations suggest that move stimulated employment at the margin by reducing the tax wedge on labor. That’s orthodoxy in public finance: shifting the burden from “goods” (work) to “bads” (pollution) improves efficiency if distribution is handled carefully. More recently, researchers modelling German carbon-tax reforms show that recycling revenue via targeted reductions in distortionary taxes outperforms undifferentiated lump-sum “climate dividends” on efficiency grounds, with options to keep reforms budget-neutral while preserving equity through complementary transfers.

Price competitiveness, especially electricity costs, is a legitimate concern for the energy-intensive industry. Berlin has not been inert. In late 2023, it agreed a power-price package that—among other measures—slashed the electricity tax for manufacturing from 1.537 ct/kWh to the EU minimum of 0.05 ct/kWh for 2024–2025, with scope to extend. Analyses through 2024 showed industrial electricity prices falling from their 2022 peaks, even as critics argued the tax cut’s scope should be broader. These steps do not overturn the logic of eco-taxes; they complement it by shielding trade-exposed firms while the clean-power supply scales and the ETS + CBAM architecture beds in. That is the real design challenge: keep the price signal for pollution, but prevent an avoidable exodus caused by temporary energy-system constraints.

Counting the Cleaning: A Transparent Estimate

Where complex numbers exist, we should use them. The EEA’s 2024 update reports 239,000 premature EU deaths from PM2.5 above WHO guidelines in 2022, alongside tens of thousands more linked to NO₂ and ozone. To monetize the burden, analysts typically apply a Value of a Statistical Life (VSL) or Value of a Life Year (VOLY) consistent with OECD guidance. Recent European policy appraisals often use VSL figures in the low-to-mid millions of euros (country-adjusted), with VOLY for sensitivity. If we apply a conservative €2–3 million VSL to PM2.5 mortality alone, the implied order-of-magnitude annual welfare loss for the EU runs into the hundreds of billions—before counting morbidity, lost productivity, or non-fatal illness. That is an estimate, not a billing invoice, but it anchors the “social cleaning” cost in numbers that matter for budgets and health ministries.

Germany-specific valuations are increasingly available as well. The 2025 Germany ETR study monetizes avoided damages using official price tags for pollution and climate, arriving at €100 billion-plus since 1999, with health benefits being the majority. A crucial detail: benefits were larger in poorer regions, which supports the claim that internalizing externalities improves fairness when exposure is unequal. For today’s policy design, this suggests a sequenced approach. Keep the fuel- and carbon-price incentives, but earmark a share of revenue for place-based support—from district heating upgrades in coal-dependent towns to targeted assistance for workers in energy-intensive plants. The efficiency story and the fairness story move together when we treat avoided hospital admissions and longer lifespans as real returns from policy, not airy co-benefits.

Not Trees Versus Taxes: Complementary, Not Substitutes

“Why don’t we just plant more trees?” Because urban trees are a local filter and climate buffer, not a substitute for source-side emissions cuts. The evidence is clear that Europe’s NO₂ exceedances come mainly from road traffic, while domestic heating and industrial sources drive particulate breaches. Trees can modestly lower PM or provide cooling; they can also, depending on canopy and street geometry, slow dispersion and trap pollutants at street level. Forestry is a both-and, not an either-or. A serious clean-air strategy tackles the combustion sources—vehicle exhaust, boilers, furnaces—through pricing, standards, and clean infrastructure, and then layers nature-based solutions on top for neighborhoods that need relief and shade the most. That hierarchy is not ideological; it is what the emission inventories and exposure maps demand.

When framed this way, the purpose of eco-taxes becomes intuitive. They steer away from the activities that generate the most significant health harms and congestion costs—exactly the non-carbon externalities that road fuels create. The OECD and transport economists have long argued that, beyond climate, pricing road use better—through distance-based charges or time-and-place differentiated tolls—can handle accidents, noise, and wear-and-tear more precisely than blunt fuel excises. In practice, countries will blend instruments. The deeper insight is that “green death” rhetoric sells a false trade-off: accept dirty air and hidden subsidies for the sake of industry or clean up and lose your factories. The evidence points to a third path: price the harm, use the money to lower other taxes and support competitiveness, and build a border regime that keeps the playing field level.

Designing Eco-Taxes People Can Live With

No tax survives without legitimacy. Public backlash is less about the principle of “polluter pays” than about who gets the money back and how fast people see benefits. In Germany and across Europe, there’s growing evidence that recycling revenue into visible, fair uses—like lowering payroll taxes, targeted energy rebates for low-income households, or investment in local heat pumps and transit—can preserve both efficiency and public support. Recent simulation work on Germany’s carbon-tax reform underscores that budget-neutral packages that cut distortionary taxes outperform simple lump-sum dividends, while still allowing equity goals to be met with targeted transfers. The message for ministries is to put the recycling line on page one, not in the annex.

The second design principle is stability with feedback. Eco-taxes must endure long enough to shape capital investment, but be tunable as conditions change. Europe’s CBAM timetable—reporting in 2023-2025; financial adjustments from 2026—is a case in point, giving firms a runway to measure embedded emissions and adjust supply chains. Meanwhile, national competitiveness measures like Germany’s electricity-tax cut for manufacturers can be time-limited bridges, not permanent crutches, while wholesale power prices normalize and clean capacity expands. Finally, we should broaden the base of pricing to cover non-carbon externalities more directly—road distance charges where congestion is acute, and standards for domestic heating that reflect its outsized role in PM exposures. Price what hurts people, and pay back what people can see.

Make the Polluter Pay, and Keep the Factory

The old bargain—cheap energy, dear lungs—was never fair, just familiar. The numbers we have now make that hard to ignore. Europe still loses hundreds of thousands of people prematurely each year to dirty air, and the implicit subsidy of underpriced fuels continues to shove those costs onto families and treasuries. Germany’s experience shows that a better bargain is possible. The ETR not only cut emissions; it saved over €100 billion in external damages, primarily by preventing illness and death, while lowering payroll taxes to support jobs. Industry today faces genuine pressures, from energy shocks to trade wars, but the answer is not to revert to hidden subsidies. It is to finish the pricing architecture—ETS plus CBAM—recycle revenues transparently to workers and firms, and accelerate clean-power build-out so energy-intensive plants can thrive on a decarbonizing grid—plant trees; of course. But do not mistake a filter for a fix. The policy test ahead is moral as much as technical: align prices with harms so the neighbor pays to clean the air they dirty, and design the transition so the machines keep running here. That, finally, is what it looks like to stop asking the public to pick up a bill it never ran up.

The original article was authored by Piero Basaglia, an Assistant Professor (Maître de conférences) at the University of Bordeaux, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Beyond carbon: The overlooked benefits of fuel taxation," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bach, S., Buslei, H., Harnisch, M., & Isaak, N. (2019). Ecological tax revenue still yields lower pension contributions and higher pensions today. DIW Berlin Weekly Report.

Basaglia, P., Behr, S. M., & Drupp, M. A. (2025). Fuel Taxation and Environmental Externalities: Evidence from the World’s Largest Environmental Tax Reform. CESifo Working Paper No. 11949.

Clean Energy Wire. (2023–2024). Germany’s electricity tax cut for industry; industrial electricity prices in 2024.

Deutsche Bundesbank/Reuters reporting via Destatis. (2025). German industrial output and exports, June 2025.

Destatis. (2025). Producer price index and industry/manufacturing dashboards.

European Commission – DG TAXUD. (2023–2025). Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM): Guidance, timeline, and exporter-leakage measures.

European Environment Agency (EEA). (2023–2024). Europe’s air quality status; Harm to human health from air pollution; Sources and emissions of air pollutants in Europe.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2023). Fossil Fuel Subsidies Data: 2023 Update.

KPMG / Baker McKenzie briefings. (2024). CBAM transitional phase and reporting obligations.

OECD. (2023). Effective Carbon Rates 2023; Taxing vehicles, fuels, and road use; VSL/VOLY guidance and valuation resources.

Rezai, A., & van der Ploeg, F. (2024). Carbon tax reform: Fair, efficient, and budget-neutral. CEPR VoxEU.

Umweltbundesamt (UBA). (2025). Final data for 2023: greenhouse gas emissions fell by 10.3%; Monitoring and projections.

Comment