Airpower Without Strategy: Indonesia’s Fighter Spree Is a Credibility Problem

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

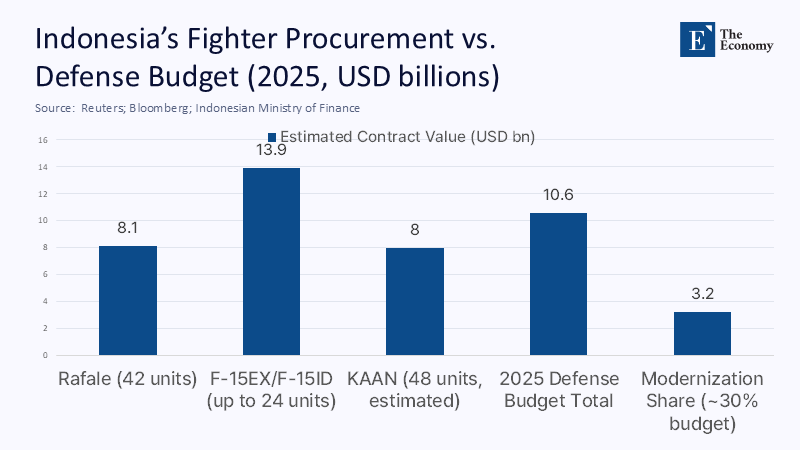

Across three calendar years, Indonesia has signed or explored fighter-aircraft buys whose sticker prices and through-life costs are wildly out of proportion to its strategy apparatus. The numbers are stark. A $8.1 billion contract for 42 Rafales is on the books, with first deliveries now slated for early 2026; a memorandum and U.S. approval remain in play for up to 24 F-15EX/F-15ID aircraft, a package once priced as high as $13.9 billion; and as of July 29, 2025, Jakarta signed a contract to purchase 48 KAAN fighters from Turkey. Even assuming phased payments, this is a notional $30+ billion portfolio against a proposed 2025 defense budget of roughly $10.6 billion. Meanwhile, Indonesia’s last defense white paper dates to 2015; its modernization program expired in 2024 without meeting targets; and its cost share in South Korea’s KF-21 program was cut to 600 billion won after years of missed payments and controversy. When procurement sprints ahead of doctrine, credibility—not capability—fails first.

Reframing the debate: credibility, not capability

The familiar argument is that Indonesia, a sprawling archipelago abutting strategic sea lanes, must diversify suppliers and recapitalize airpower. That proposition is not wrong; it is radically incomplete. The deeper problem is reputational. Without a current white paper to anchor force design, and with the Minimum Essential Force plan lapsed unmet in 2024, big-ticket fighter contracts become signals of fiscal opportunism and policy drift, not deterrence. The renegotiation that slashed Indonesia’s KF-21 cost share to 600 billion won, coming after arrears and a still-unresolved police probe into alleged attempted data theft by Indonesian engineers in Korea, compounds the trust deficit with partners and primes future vendors to demand tougher milestones and escrow. An air force can be rebuilt; a reputation for reliability is slower to repair. Jakarta’s first task, then, is not more aircraft—it is an unambiguous policy architecture that makes each procurement legible, financed, and defensible.

An airpower cart before the strategy horse

Indonesia’s shopping list now straddles French Rafales, prospective F-15EX/F-15ID, a signed Turkish KAAN contract, and reports of evaluating China’s J-10. This diversification is often justified as embargo insurance. Yet without a published threat prioritization since 2015, diversification multiplies maintenance pipelines, training loads, and interoperability friction, while sending contradictory diplomatic signals. East Asia Forum rightly notes there has been no updated white paper since 2015 and that the modernization plan expired last year; a successor “Optimum Essential Force” remains undefined in public. The result is an acquisition treadmill shaped by political calendars more than joint doctrine. Even interim moves have stumbled: Jakarta delayed a stopgap Mirage 2000-5 deal on fiscal grounds, undercutting the notion of stable cash flow for new fleets. Strategy does not forbid fighters; it sequences them against mission need, workforce, and sustainment capacity. At present, procurement looks less like sequencing and more like shopping with a moving target.

The numbers don’t add up

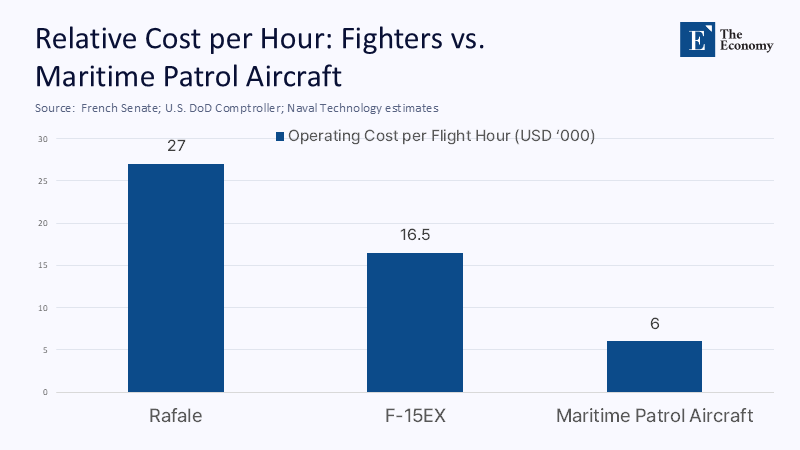

Affordability is not a slogan; it is math. Start with procurement. Rafales: $8.1 billion for 42 aircraft, delivery of the first six expected in early 2026. F-15EX: The U.S. approved a package valued up to $13.9 billion; the flyaway cost for recent U.S. lots is about $90 million per jet. KAAN: a signed Indonesian contract for 48 aircraft, with no official price disclosed, plausibly implies multi-billion-dollar exposure across development and sustainment. Now add operations. France’s 2024 Senate report puts the Rafale’s flying-hour cost at roughly €25,000; U.S. DoD FY2024 reimbursable rates list the F-15EX at about $16,000–$17,000 per hour, excluding many ownership overheads. Stack those lifecycle costs against a 2025 defense budget proposal of IDR 165.2 trillion (~$10.6 billion), more than half of which typically goes to personnel and management support, with modernization a minority share. The budget ceiling is absolute; the physics of sustainment are unforgiving. Buying three overlapping fighter ecosystems under such constraints is not prudent hedging; it is structural overreach.

A maritime state chasing air superiority

Indonesia is an oceanic country with one of the world’s longest coastlines—about 54,716 kilometers by CIA methodology—and recurring gray-zone pressure near the Natuna Islands. The core operational problem is maritime domain awareness, patrol persistence, and integrated air-maritime command and control, not high-end air superiority over distant airspace. Incursions by Chinese coast guard units have repeatedly tested Indonesia’s ability to protect survey activity and fisheries in the North Natuna Sea. For this mission set, long-range radar coverage, networked ground-based air defense, maritime patrol aircraft, and ready coast guard cutters typically dominate marginal returns on investment. Fighters matter at the edge of escalation; they are expensive to keep on station, and—without the enablers—symbolic. Indonesia’s money would buy more deterrence by saturating its archipelagic lanes with sensors and patrol capacity than by proliferating fighter types whose best use cases lie far from the water—sequencing matters: sea control first, then boutique airpower.

Trust, technology, and the KF-21 lesson

The KF-21 episode is a case study in why partners are skittish. Indonesia’s share, originally around 20% of development costs, slipped into arrears, then was renegotiated downward this June to 600 billion won. Layered atop the money trouble was a reputational shock: South Korean authorities raided KAI’s headquarters in March 2024 as part of a probe into alleged attempts by Indonesian engineers to remove confidential data on USB drives. Indonesian authorities have denied wrongdoing and said they are investigating, but the political damage is already done: program managers will now calibrate cooperation to the lowest common denominator of trust. For Indonesia, that translates into thinner technology transfer and stricter conditionality across future joint projects. The strategic price of opacity is paid in foregone capability; the strategic premium for credibility is paid in easier financing and deeper integration. Procurement is policy—because it teaches others what to expect next time.

What a coherent path would look like

A harsh but constructive path forward starts with governance, not kit. Publish a 2025–2030 defense white paper that sets unambiguous mission priorities—maritime domain awareness, air defense of critical infrastructure, and crisis-response mobility—then tie every procurement line to those missions with dated milestones, workforce plans, and sustainment tails attached. Consolidate fighter choices into one principal platform plus a light-combat/trainer solution to shrink training and maintenance burden; pause new fighter signatures until enablers catch up. Reform industrial cooperation: put all tech-transfer projects on escrow-backed, milestone-based payments with explicit clawbacks for slippage; accept narrower tech-transfer in exchange for precise delivery and IP compliance. Shift near-term capital toward ISR radars, maritime patrol aircraft, and command-and-control networks that turn contested waters into a sensor-rich deterrent. Finally, make credibility operational: publish annual delivery scorecards and independent readiness audits. Partners forgive ambition; they punish opacity.

Anticipating the critiques—and answering them

Two objections recur. First, Indonesia faces a rising China and needs top-tier fighters to signal resolve. True, but the Natuna problem is a contest of presence and enforcement before it is a contest of air-to-air prowess. Coastguard cutters, maritime aviation, and integrated sensors create the facts on—and above—the water that fighters later defend. Second, that diversification hedges against embargo risk. Again, true, but diversification without interoperability and funding discipline only reproduces the 1990s problem in a more complex fleet. The lesson of the Rafale/F-15/KAAN triad is not that any particular airframe is wrong; it is that three overlapping sustainment pipelines are a tax on readiness that a $10–11 billion defense budget cannot pay. A strategy-first approach does not deny jets; it sequences them after the state has bought the infrastructure that makes them militarily, fiscally, and diplomatically credible.

Credibility before combat power

Indonesia’s leaders can still convert this spree into a strategy. The way out is simple, if not easy: publish a doctrine that tells partners what the country is for, show a ledger that proves how it will pay for it, and sequence modernization so that enablers precede prestige. The record of the past year—renegotiated obligations, proliferating vendor relationships, and controversy around a flagship joint program—has eroded the single asset no amount of hardware can buy: credibility. The proper signal now would be a moratorium on fresh fighter deals until a new white paper is on the street, radar coverage and maritime patrols are funded, and the KF-21 commitments are honored to the letter of the renegotiated agreement. In a naval state, control of sea and sky begins with governance. Airpower purchased without a strategy invites doubt; airpower aligned to a public plan restores trust. The choice is not between weakness and strength. It is between noise and coherence, and time is nearly up.

The original article was authored by Pieter Pandie, a researcher in the International Relations department at CSIS Indonesia. The English version, titled "Indonesia's fighter jet shopping spree exposes strategy gap," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Aviationist. (2024, March 20). Indonesian Engineers Under Investigation For South Korean KF-21 Boramae Data Leak Attempt.

Bloomberg. (2025, June 13). South Korea Agrees to Cut Indonesia Share in Fighter Jet Project.

CIA World Factbook. (2024). Indonesia — Geography (Coastline).

Comptroller of the U.S. Department of Defense. (2023). FY2024 Reimbursable Rates (Fixed Wing) — F-15EX.

East Asia Forum. (2025, August 8). Indonesia’s fighter-jet shopping spree exposes strategy gap.

Financial Times. (2024, November 14). Indonesia says it drove Chinese coastguard ships out of disputed waters.

FlightGlobal. (2024, February 1). Seoul probes Indonesian engineers over alleged KF-21 technical theft.

FlightGlobal. (2025, May 23). Alleged USB data theft continues to cloud Indonesia’s KF-21 participation.

French Senate. (2024). Rapport d’information — coûts d’heure de vol du Rafale (approx. €25,000).

Library of Congress. (2015). Defence White Paper, 2015 (Indonesia).

Reuters. (2022, February 10). France seals $8.1 billion deal with Indonesia to sell 42 Rafale jets.

Reuters. (2023, August 22). Indonesia, Boeing sign deal for sale of F-15 fighter jets (up to 24).

Reuters. (2024, January 3). Indonesia delays buying used fighter jets, cites fiscal limits (Mirage 2000-5).

Reuters. (2025, May 28). France’s Macron, Indonesia’s Prabowo to discuss defence ties (Rafale deliveries early 2026).

Reuters. (2025, June 4). Indonesia weighing purchase of China’s J-10 fighter jets.

Reuters. (2025, June 13). Indonesia to cut contribution to South Korea fighter jet project (KF-21 cost share to 600bn won).

Reuters. (2025, July 29). Indonesia signs contract with Turkey to buy 48 KAAN fighter jets.

The Diplomat. (2025, July 15). Indonesia Is Out of Step With the Global Arms Race (MEF lapse).

U.S. Department of Defense Comptroller. (2024). FY2025 DoD Fixed-Wing Reimbursable Rates (context).

Comment