When the Market Leaves the Stadium: Why “Money” Is Quietly Migrating Beyond Basel

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

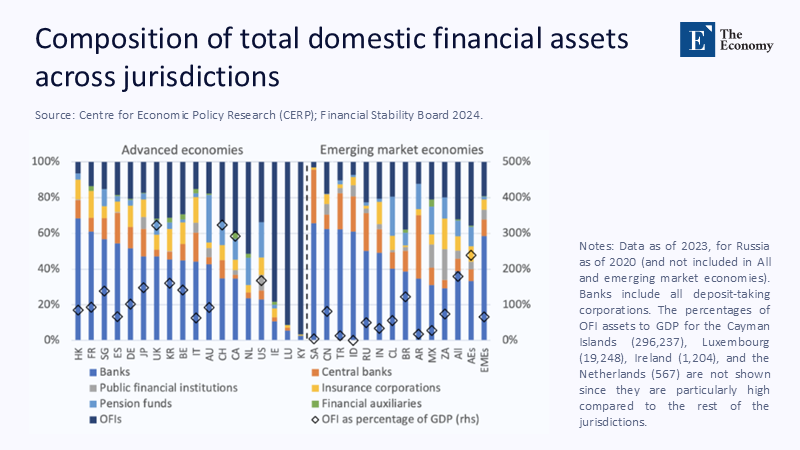

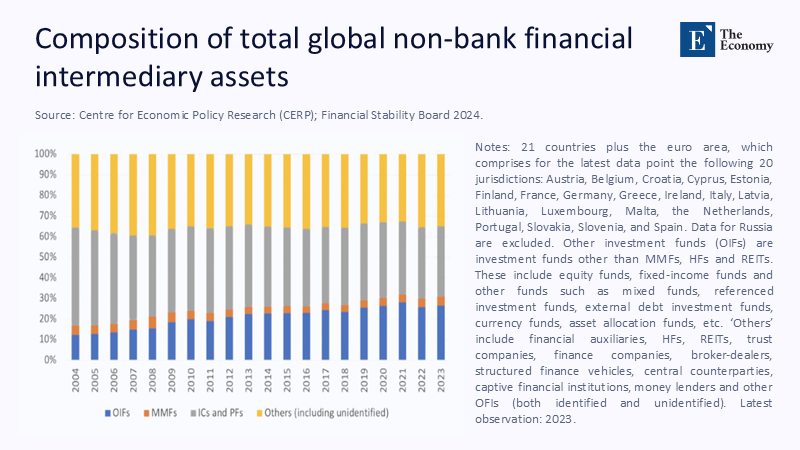

By the end of 2023, nearly half of all global financial assets—49.1%—were held outside the traditional banking system, in what regulators call nonbank financial intermediation (NBFI). At the same time, fiat-pegged stablecoins were moving hundreds of billions of dollars a month on public blockchains, with Visa’s analytics showing adjusted 30-day volumes in the high hundreds of billions and the Financial Times reporting $752 billion in a single recent month alongside a record 46 million active wallets. Meanwhile, tokenised U.S. Treasuries on public chains surged past $5 billion in March 2025 and have kept climbing. This is not a “Lehman” setup, a reference to the 2008 financial crisis triggered by the collapse of Lehman Brothers. It’s a jurisdictional migration. As nonbanks and tokens scale, the officially regulated “money market” is becoming a smaller island in a widening ocean of off-perimeter liquidity. The proper comparison isn’t bank runs; it’s stablecoins quietly bypassing conventional payment rails while NBFIs do the same to funding markets. The question isn’t whether the fence holds. It’s whether the game has already moved to the field outside.

Reframing the Problem: From Crisis Narratives to Jurisdictional Displacement

The prevailing storyline warns that NBFIs amplify shocks and could ignite the next systemic crisis. That risk exists, but it misses the larger shift illuminated by recent research: activity is migrating beyond the Basel perimeter because rules optimized for banks are binding, while alternative channels offer speed, yield, and looser constraints. The VoxEU synthesis of new International Banking Research Network work shows how nonbanks transmit liquidity shocks and why investment funds have become central to funding flows. Read that not as a forecast of imminent collapse, but as an x-ray of a market that has already re-routed. This is the same pattern we see in stablecoins: instead of attacking the stadium, players discovered an uncrowded field outside the walls and set up a different scoreboard. Regulation inside the stadium keeps improving; the game, however, drifts to where frictions are lower. If policy responds as if we’re still policing exits instead of redrawing the pitch, it will keep losing field position.

The New Perimeter: What Counts as the “Money Market” Now

“Money market” used to mean bank-centric wholesale funding plus regulated money market funds. Today, the edges blur. In the U.S., money market fund assets stood at $6.16 trillion at the end of September 2023—already reflecting deposit flight and higher yields—while flows have remained elevated since. Private credit—largely intermediated by nonbanks—has scaled to about $1.6 trillion in assets under management, seeding new pipelines of short-term financing that never touch bank balance sheets. And on public ledgers, tokenised cash equivalents and tokenised Treasuries add settlement tools that behave like cash in specific contexts. None of these rails is identical to insured deposits or central-bank reserves; together, though, they form a parallel liquidity complex with distinct gatekeepers, data, and stress points. When a meaningful share of short-term funding and near-money instruments live there, debating the old boundaries begins to look like arguing over a map that no longer matches the roads.

Transmission, Revisited: Liquidity Channels in an Off-Pitch Market

If money is flowing outside the stadium, how do shocks travel? The new IBRN evidence shows open-end funds transmit monetary surprises to flows and pricing, especially where liquidity transformation is largest. European and U.S. funds display asymmetric sensitivities by investor type, and the flow-performance feedback loop is stronger when assets are hard to price in real time. That is where redemptions, stale NAVs, and dash-for-cash dynamics meet the absence of a lender of last resort. In parallel, regulators from the FSB to IOSCO argue that liquidity management tools—swing pricing, anti-dilution levies, gates—should be pre-positioned, not improvised mid-crisis. This is not the same contagion channel as bank runs; it is a price-liquidity spiral in vehicles that promise daily liquidity on portfolios that settle slowly. Think of drains and gutters rather than bursting pipes. The mechanism differs, but the speed is just as unforgiving in a sell-first world.

Payments to Funding: The Stablecoin–NBFI Parallel

Stablecoins began as a trading lubricant, but their footprint has widened into cross-border settlement and corporate treasury use in places where traditional rails are slow or costly. Visa’s public dashboard shows sizable adjusted monthly volumes. The FT reports $752 billion in monthly stablecoin transactions and 46 million active wallets. Reuters puts outstanding supply above $260 billion in mid-2025, 99% of it dollar-pegged. In Europe, MiCA’s stablecoin rules started applying in mid-2024, prompting reshuffling among euro-denominated tokens and signaling that policy is catching up. The analogy to nonbanks is tight: both leverage safe assets for speed and yield; both avoid the Basel choke points; both are becoming essential infrastructure in specific corridors and asset classes. Neither looks like a bank; both now matter to what we mean by “money.” Treating them as curiosities risks discovering, too late, that the bridge everyone is already using isn’t on the official map.

Method, Not Mystique: How the Numbers Were Built

The evidence base is deliberately mixed. System-level shares and growth rates draw on the FSB’s 2024 Global Monitoring Report—the most comprehensive cross-jurisdictional census of NBFI assets—which places the sector at 49.1% of global financial assets and the risk-focused “narrow measure” at a record $70.2 trillion. Fund-level transmission is synthesized from the VoxEU overview of IBRN studies published in August 2025. Magnitudes for money market funds are anchored to the OFR Money Market Fund Monitor. Tokenisation metrics rely on RWA.xyz aggregates and contemporaneous reporting that tokenised U.S. Treasuries surpassed $5 billion, with the caveat that on-chain totals update continuously. Stablecoin usage is cross-checked using Visa’s analytics, Financial Times volume, and wallet snapshots, and Reuters supply figures. The purpose is not to privilege a single dataset, but to show—transparently—how multiple primary sources converge on the same structural story.

Policy for a Token-Market Era: Your Role in Shaping a perimeter-Neutral Financial Landscape

If the game is outside, the rules must travel. First, make liquidity risk tools perimeter-neutral. Daily-dealing funds that transform liquidity should carry pre-set swing pricing or anti-dilution mechanisms as standard—regardless of domicile—and publish real-time liquidity metrics to supervisors. Second, adopt activity-based rules for short-term funding, including minimum buffers and stress-testing for entities that borrow against liquid government collateral to fund illiquid assets. Third, extend settlement-tier safeguards to tokenised cash: wallet-level KYC for institutional stablecoin rails; disclosure and audit of reserves; and explicit resolution regimes. Fourth, build the connective tissue: cross-border supervisory colleges for NBFIs; data hooks into on-chain settlement; and contingency liquidity lines that can be activated for systemic nonbanks in exchange for strict conditions. The FSB’s 2025 recommendations on leverage and the BIS “unified ledger” concept both point the way: regulate the function, not the form, and stop assuming that risk respects the turnstiles of the old stadium.

Anticipating the Pushback: Why This Isn’t “Over-Regulate Everything”

Skeptics will argue that tokenised money is still small and that nonbanks have weathered multiple shocks. Both points are partly valid—and beside the point. Tokenised Treasuries are a rounding error next to the $27 trillion U.S. Treasury market, but their purpose is not scale; it is interoperability, where speed and programmability change behaviors at the margin that add up in the aggregate. Private credit has delivered attractive risk-adjusted returns, but evergreen vehicles with partial redemptions create pressures that don’t appear in closed-end structures. Europe’s debate over centralising securities supervision underlines how fragmented oversight leaves gaps right where funds and platforms scale across borders. The correct response is not to smother innovation or to deputise nonbanks as quasi-banks; it is to make the new field playable by the same core safety rules and to give referees a line of sight wherever the ball moves. That is not over-regulation. It is basic governance for a market that stopped asking permission to leave the stadium.

What Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers Should Do Next

Educators should update curricula to reflect how funding and payments now operate in practice, teaching liquidity transformation outside banking, tokenised settlement mechanics, and cross-border supervisory cooperation as first-order topics, not electives. University treasurers and public administrators should pilot low-risk use cases—tokenised cash equivalents for cross-border tuition or vendor payments where rules allow—paired with strict custody, KYC, and accounting controls. Policymakers should hard-wire perimeter-neutral LMTs into open-end funds, accelerate data-sharing arrangements for nonbanks, and require stablecoin issuers serving their residents to meet the same disclosure, audit, and resolution standards as e-money providers. MiCA’s phased regime shows one credible path; the FSB’s leverage framework adds bite on funding risks; and the BIS’s unified-ledger work sketches a settlement future that can coexist with banks without pretending everything must be a bank. Build for coexistence, not conversion. The stadium stays. The field outside gets floodlights and rules.

The Scoreboard Is Moving

We built the 20th-century financial system to be measured from inside a walled stadium. Bank capital and liquidity rules were the fence; central bank money was the grass underfoot. But markets have been voting with their feet. When half of global assets sit with nonbanks, when hundreds of billions in tokenised dollars settle every month, and when tokenised Treasuries reach billions on public rails, the scoreboard cannot stay fixed to the stadium wall. This is not a collapse story; it is jurisdictional displacement at scale—liquidity, credit, and settlement migrating to venues designed for speed and programmability. The fix is not to chase shadows back inside. It is to move the officials, redraw the lines, and apply the core safety rules wherever the game is played. If we do that now—perimeter-neutral liquidity tools, activity-based funding oversight, auditable tokenised cash—we will stop litigating yesterday’s crisis and start governing tomorrow’s money. The market has already left the stadium. Policy should catch up before the floodlights go out.

The original article was authored by Falko Fecht and Linda S. Goldberg. The English version of the article, titled "Transmission of liquidity shocks through non-bank financial intermediaries: Evidence from the International Banking Research Network," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bank for International Settlements (BIS). (2024). Annual Economic Report 2024 (esp. overview on NBFIs and regulatory perimeter). Retrieved August 2025.

Bank for International Settlements – Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI). (2024). Tokenisation in the context of money and other assets: concepts and taxonomy (CPMI d225). Retrieved August 2025.

Chainalysis. (2024). The 2024 Geography of Cryptocurrency Report (PDF: regional stablecoin share and usage patterns). Retrieved August 2025.

European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA). (2024). Opinion: Reforms to improve resilience of Money Market Funds (overview of EU MMF reform direction). Retrieved August 2025.

European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB). (2024). Response to ESMA consultation on Liquidity Management Tools for open-ended funds (supports LMTs across OEFs). Retrieved August 2025.

Financial Stability Board (FSB). (2024). Global Monitoring Report on Nonbank Financial Intermediation 2024 (NBFI size 49.1% of global financial assets; narrow measure $70.2T). Retrieved August 2025.

Financial Stability Board (FSB). (2025). Leverage in Nonbank Financial Intermediation: Final Report (integrated policy approach to NBFI leverage). Retrieved August 2025.

Financial Times. (2025, 12 Jun). How stablecoins are entering the financial mainstream (monthly volumes and wallet counts from Visa data). Retrieved August 2025.

McKinsey & Company. (2025). The stable door opens: How tokenized cash enables next-gen payments (payments use cases and 2025 inflection framing). Retrieved August 2025.

MiCA Papers. (2023–2024). MiCA Implementation Timeline (stablecoin rules effective 30 Jun 2024; broader regime 30 Dec 2024). Retrieved August 2025.

Office of Financial Research (OFR). (2023). Money Market Fund Monitor – Quarterly Snapshot (MMF assets at $6.16T end-September 2023). Retrieved August 2025.

PitchBook / White & Case summary of Preqin data. (2025). Breaking new ground on the next phase of private credit (private credit AUM ≈ $1.6T). Retrieved August 2025.

Reuters. (2025, 24 Jun). Central bank body BIS delivers stark stablecoin warning (stablecoin supply >$260B; 99% USD-pegged). Retrieved August 2025.

RWA.xyz. (2025). Tokenized U.S. Treasuries tracker (live aggregate value of tokenised Treasuries; surpassed $5B in March 2025). Retrieved August 2025.

Visa. (2025). Onchain Analytics Dashboard: Transactions and Addresses (adjusted monthly stablecoin volumes; active wallets). Retrieved August 2025.

VoxEU/CEPR – Fecht, F., & Goldberg, L. (2025, 5 Aug). Transmission of liquidity shocks through nonbank financial intermediaries: Evidence from the IBRN. Retrieved August 2025.

Comment