Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

India now carries the demographic crown, but headcounts don’t power factories or fill pipes. In 2023, the United Nations confirmed India overtook China as the world’s most populous nation and is set to keep widening the gap into the 2060s. At the same time, the World Resources Institute classifies India among the most water-stressed countries globally, with one quarter of humanity living in places facing extreme water stress each year. The International Energy Agency projects India will be the largest single source of oil demand growth through 2030 and a major driver of global gas demand—meaning any wobble in energy supply or price cascades straight into inflation, jobs, and public finances. Those three facts, taken together, frame the real test: demography has delivered scale, but only resource security—water, energy, and critical minerals tied to resilient grids—will turn that scale into sustained, broad-based prosperity.

Reframing the Debate: From People to Pipelines

The familiar story says India’s young population guarantees a long growth runway while a greying China slows. That story is now dangerously incomplete. Demography is the capacity to learn, build, and consume; resource security is the capacity to deliver—to keep turbines spinning, cities supplied, and export schedules intact under stress. China’s rise, commonly attributed to manufacturing prowess and scale, was underwritten by a quiet, decades-long sprint to secure inputs: coal, oil, gas, water transfer projects, and—well before EVs went mainstream—dominance in refining the minerals that clean energy needs. India’s growth, by contrast, still depends heavily on imported hydrocarbons, stressed aquifers, and fragmented infrastructure. The shift we need is conceptual and immediate: industrial and education policy must be yoked to a national resource strategy that treats water, energy, and minerals as complex preconditions for learning outcomes, productivity, and jobs, not as afterthoughts to be “fixed later.”

This reframing matters now because the cushion of cheap energy that flattered macro numbers is thinning. Since 2022, discounted Russian crude has lowered India’s oil import bill by several billions of dollars, cushioning consumers and keeping the current account in check. But discounts have narrowed markedly in 2024–2025; traders report the smallest gaps to Brent since 2022, and state refiners have occasionally paused purchases as economics turned. The trendline is clear: a world of tighter sanctions, concentrated trading, and geopolitics leaves India paying more for energy just as demand stays strong. In that world, productivity gains from water efficiency, grid investment, and mineral security aren’t “green extras.” They are the main act, protecting growth from imported volatility.

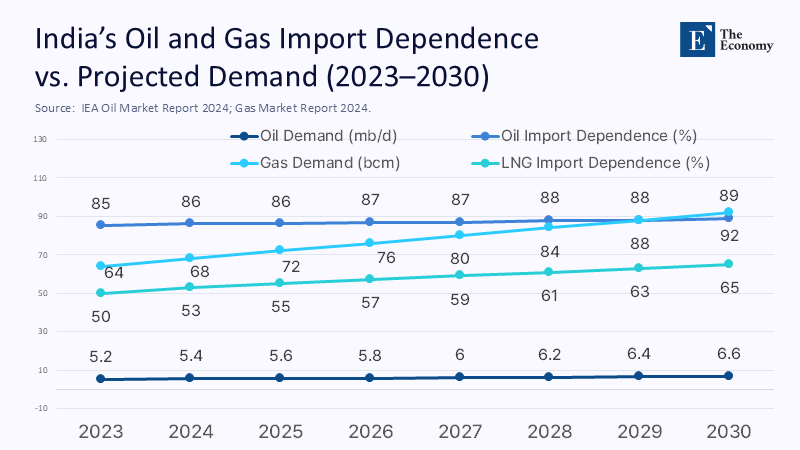

The Discount Ends: Energy Security After the Russian Windfall

Between FY2023 and FY2024, analysts estimate India saved roughly $5–8 billion by substituting discounted Russian barrels for costlier Middle Eastern grades, with Russia at times supplying around a third or more of India’s crude. That window brought breathing room for households and industry. It will not last as a strategy. The IEA expects India to account for the single most significant increase in global oil demand through 2030; it also sees gas demand rising sharply, doubling LNG imports as domestic production lags. These are structural pulls. Even with efficient refineries and savvy trading, a growth model reliant on ever-larger fossil imports is exposed to price spikes, shipping disruptions, and policy shocks. The real hedge is twofold: lock long-term LNG and crude contracts with flexible pricing and destination clauses, while accelerating the build-out of low-carbon electricity so industry can increasingly swap imported molecules for domestically generated electrons.

The good news is India’s grid is quietly getting more capable. In May 2024, the country met a record 250 GW of demand, primarily during solar hours, with only a fractional shortage; peak demand met rose to around 250 GW in FY2024–25, indicating better balancing. Transmission plans to integrate over 500 GW of non-fossil capacity by 2030 are underway, supported by Green Energy Corridors and new storage mandates. Coal remains a significant share of generation, but the system is proving it can meet peaks without running the entire thermal fleet, a sign that renewables, storage, and smarter dispatch are bending the curve. The policy implication is stark: every rupee that hardens transmission, integrates storage, and improves distribution efficiency reduces India’s exposure to imported energy volatility and frees scarce foreign exchange for minerals, machinery, and education.

Water Before Wafers: The Infrastructure India Must Build First

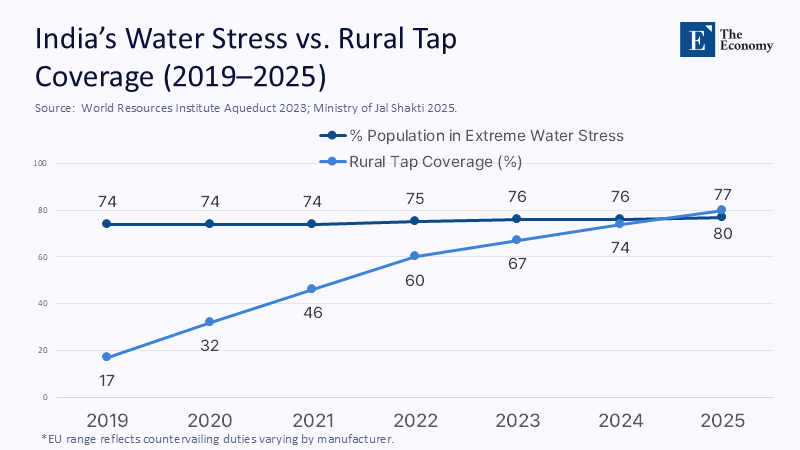

Nothing is more basic—or more overlooked—than reliable, potable water at scale. India sits in the “extremely high” water-stress cohort, and recent heatwaves have turned urban water fragility into a lived reality from Delhi to Bengaluru. At root, three problems compound: declining per-capita water availability, chronic non-revenue water losses in cities, and delayed wastewater treatment and reuse. The Jal Jeevan Mission, a government initiative aimed at providing safe and adequate drinking water through individual household tap connections by 2024, has been a genuine inflection point. It has lifted rural tap coverage from about 17% in 2019 to roughly 80% by February 2025, with funding extended through 2028. That is a public-health victory and a social productivity boost. Yet coverage is not the same as a continuous, quality supply. In many urban systems, non-revenue water near 40% means vast losses to leaks, theft, and metering gaps—waste a capital-tight country cannot afford.

A resource-first strategy puts water efficiency on par with energy security. That means utilities funded to fix leaks and district-metered areas; enforceable service standards for 24x7 supply in dense nodes; industrial parks obligated to use a rising share of treated wastewater; and agricultural programs that couple micro-irrigation with precise power pricing and soil moisture data. India needs more water storage, yes—but it needs more innovative use far more. The payoff shows up everywhere: better school attendance when girls aren’t hauling water; healthier workers; fewer migration shocks; and lower capital requirements for power, since water pumping and treatment are significant electricity loads. If we want high-tech manufacturing, we need “water tech” first: pipes that don’t leak, meters that bill fairly, sensors that catch losses in real time, and treatment that feeds back into industry.

Minerals, Not Just Markets: Catching Up to China’s External Footprint

China’s speed from scarcity to security came from relentless mid-stream control. It refined and processed the minerals behind EVs and renewables—cobalt, graphite, rare earths, lithium—at a scale the rest of the world is still struggling to match. Today, China processes most of the world’s cobalt and graphite and dominates rare-earth refining; together with Indonesia, it accounted for about 90% of global additions to nickel refining capacity in 2024. Beijing has wielded that dominance through export controls, most prominently on graphite and select rare-earth products, reminding everyone that refining power is market power. India, aiming to grow batteries and clean-tech manufacturing, must assume that Chinese midstream leverage will persist and occasionally tighten. The response is neither slogans nor autarky—it is portfolio diversification grounded in deals that move tonnage.

Here, the machinery is starting to turn. The government’s KABIL vehicle has secured exploration and exclusive rights over lithium brine blocks in Argentina. It is deepening a critical minerals partnership with Australia that has already identified target projects. India has courted African partners—from Namibia’s uranium and critical minerals ecosystem to exploratory missions in Chile and beyond—while putting 30 critical minerals on an official list to align policy and finance. On the demand side, India’s EV roadmap implies battery demand between roughly 100 and 260 GWh by 2030. None of this closes the gap with China overnight; it does create optionality. The rule is simple: convert MoUs to offtake contracts; convert offtake to equity stakes where sensible; and build domestic refining where input streams are secure enough to lower finance costs.

Domestic Substitution: Efficiency, Recycling, and the Grid as Industrial Policy

A resource-first strategy is not only about securing supply abroad; it is about demanding less per unit of GDP at home. Three levers are decisive. First, electricity: continue the rapid expansion of renewables, but match it with transmission build-out and storage required to treat renewables as firm industrial power. The country’s ability to meet a 250 GW peak during solar hours with minimal shortage is a proof point worth scaling. Second, efficiency: distribution companies should be paid to reduce losses—water and power—because each percentage point of aggregate technical and commercial loss saved is equivalent to adding free capacity to the system. Third, recycling: a serious national program for battery and electronics recycling can hedge mineral imports and create a domestic secondary supply of cobalt, nickel, copper, and lithium in the 2030s, aligning with the ramp-up in EV adoption.

Methodologically, we can be transparent about magnitudes if India reaches the government’s 2030 EV sales penetration goals—around 30% for private cars and higher for two-/three-wheelers—annual battery demand plausibly lands in the IEA- and NITI-consistent 100–260 GWh range depending on duty cycles and grid storage. Even a mid-case of 170 GWh implies tight markets for graphite anodes and lithium chemicals unless recycling ramps and offtakes diversify. On power, Central Electricity Authority transmission plans call for tens of thousands of circuit-kilometers and significant new substation capacity to integrate >500 GW of non-fossil by 2030; those numbers translate into very concrete steel, copper, and financing needs that industrial policy must front-load, not chase. The analytic point is simple: efficiency and grids are a resource strategy, because they shrink the volume of minerals and molecules you must import to support each incremental unit of growth.

Anticipating the Pushback—and Why It Fails

One critique says India can lean on global spot markets and flexibility, as it long has, and avoid tying up capital in long-dated resource deals. That view ignores how concentrated and politicized commodity mid-streams have become. China and Indonesia effectively cornered new nickel refining capacity in 2024; China continues to hold commanding shares in graphite and rare earths, and it has shown a willingness to use export licensing to manage flows. Meanwhile, India’s role as the most significant driver of oil demand growth this decade means price risk rises with success; volatility taxes the poor first. The task, then, is not to renounce markets but to bind them with contracts, logistics, and domestic buffers so that teachers, factory managers, and hospital administrators can plan with confidence.

A second critique says state capacity is the bottleneck, not resources. There is truth here, but 2024–2025 data also show the state doing more with infrastructure than cynics concede. Meeting a 250 GW peak with marginal shortage, commissioning thousands of circuit-kilometers of new transmission, and financing a multi-year rural tap-water expansion to ~80% coverage are not small feats. The fix is management and measurement: independent water-and-power regulators enforcing service standards; public dashboards tracking leak repairs and pressure; and disciplined use of concessional capital for grid storage and wastewater reuse where social returns exceed private ones. For educators and administrators, the gains come in minutes and money saved—fewer school closures for heat or shortages; steadier lab operations; budgets not chewed up by diesel back-up and tanker purchases. The macroeconomy shows up as attendance, pass rates, and factory utilization—metrics that move because pipes and wires did.

Make Water, Minerals, and Grids the First Line in Every Education and Growth Plan

Policy begins with a sober premise: India has the people; it must now guarantee the inputs. The UN’s demographic charts will not mitigate a heatwave or finance an LNG cargo. WRI’s water maps will not mend a leaking main. IEA’s oil and gas projections will not prevent discounts from narrowing or geopolitics from spiking freight. What will: a national agenda that treats water efficiency as economic infrastructure, locks in long-term energy and mineral offtakes beyond any one bilateral relationship, and builds a grid that can move cheap, clean power to where firms and schools need it, when they need it. This is not about replicating China’s path but about absorbing its lesson: planning for inputs precedes prosperity. Suppose India prioritizes water, minerals, and wires in its budgets and syllabi. In that case, the demographic dividend will have pipes and power to run through—and the ambition of feeding, educating, and employing 1.4 billion people will feel less like a miracle and more like a plan.

The original article was authored by Dr Huw McKay, a Visiting Fellow in the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University. The English version, titled "India’s burgeoning population lead over China will not be enough to fully close the resource demand gap," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Central Water Commission (CWC). (2019, January). Per Capita Water Availability in India – decreasing and likely to decline further. Press Information Bureau.

CleanTechnica. (2023, August 18). 25 Countries & 25% of World Population Face Extremely High Water Stress.

CREA (Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air). (2025, April/May). India Energy Overview FY 2024–25; Record renewables capacity in FY24-25 signals India’s path beyond coal.

CSIS. (2023, December). China’s New Graphite Restrictions. https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-new-graphite-restrictions

IEA. (2023). Indian Oil Market: Outlook to 2030 (Report).

IEA. (2024). World Energy Outlook 2024 – Executive Summary; Growth in global energy demand surged in 2024.

IEA. (2025). Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025 – Executive Summary.

KABIL (Khanij Bidesh India Ltd.). (2024–2025). Argentina lithium blocks – exploration started.

Le Monde. (2024, June 20). Water war rages on in Delhi, crushed by a historic heatwave.

Ministry of Power, Government of India. (2024–2025). Power demand met at 250 GW; Transmission plan for integration of >500 GW non-fossil by 2030. Press Information Bureau releases.

PIB (Ministry of Jal Shakti). (2025, February 1). Jal Jeevan Mission coverage ~80%; Mission extended to 2028 (Budget 2025–26).

Reuters. (2025). India gas demand to surge by 2030, doubling LNG imports; Urals discounts narrow; intermediaries squeezed in India trade; related coverage on Indian purchases.

Times of India / Economic Times EnergyWorld. (2024–2025). India saved $7.9 bn in FY24 via discounted Russian crude; India targets 30% EV sales by 2030.

UN DESA. (2023–2024). Policy Brief 153: India overtakes China as the world’s most populous country; World Population Prospects 2024.

WRI (World Resources Institute). (2023). 25 Countries Face Extremely High Water Stress; Aqueduct 4.0 Rankings and Atlas

Comment