Urgent Shift: China’s Economic Model Must Prioritize Households Over Surplus

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

China ended 2024 posting one of the largest annual goods trade surpluses on record and entered mid-2025 with exports still resilient despite cyclical dips and stop-start tariff truces with Washington. That headline has been misread as triumph. It is the mirror image of a domestic economy still underpowered by households after a four-year property slump, and of local governments weighed down by legacy debts that crimp service delivery and confidence. In June 2025, official data showed new-home prices down 3.2% year on year, real-estate investment in the first half fell 11.2%, and new housing starts dropped roughly 20%. At the same time, household deposits surpassed 160 trillion yuan by March, approximately 118% of 2024 GDP—an unmistakable signal of precautionary saving in the face of asset-price and income uncertainty. The central problem is not the U.S.–China conflict per se; it is the collapse of the property-driven wealth effect and the persistence of an export-first model that no longer enjoys a social license abroad. The remedy is equally clear: a durable pivot to domestic, household-led demand.

Redefining the Issue: It's About Balance Sheets, Not Geopolitics.

The slowdown has domestic origins. A long property boom that once underpinned household wealth and local revenues turned pro-cyclical and deflationary after 2021. By June 2025, the official 70-city index recorded another monthly drop and a 3.2% annual decline, while developers slashed investment and new starts. As land-sale income dried up, local governments tightened their belts. The IMF’s spring 2025 Financial Sector Assessment flagged significant exposures to local-government financing vehicles (LGFVs), while multiple estimates place overall LGFV liabilities near 60 trillion yuan at end-2023—roughly half of GDP. Households see fiscal strain, unfinished housing, and weaker job prospects; they respond by paying down debt and parking cash in deposits, despite deposit rates slipping under 1% in some maturities. The export surplus thus reflects under-consumption at home, not structural invincibility abroad. Policy that treats the symptom—exports—while ignoring the cause—repairing household and local-government balance sheets—will underperform.

The counterfactual is instructive. Had property valuations held another decade and a broad-based property tax been in place, local finances might have stabilized on a more predictable basis. But Beijing never rolled out a nationwide levy beyond limited pilots; when the market turned, that fiscal bridge was not there. Attempts to revive sentiment through lower down-payments, transaction-tax tweaks, and developer support helped at the margin, yet price declines persisted into mid-2025. The scale of the adjustment means incremental measures cannot restore the old model. The correct target is household security and local fiscal capacity, not more supply-side pressure on foreign markets. A strategy that places the consumer at the center—permanently—addresses the root of weak demand and reduces the political blowback now ricocheting through advanced economies.

The Export Backlash: Overcapacity, EVs, and Shrinking Patience Abroad

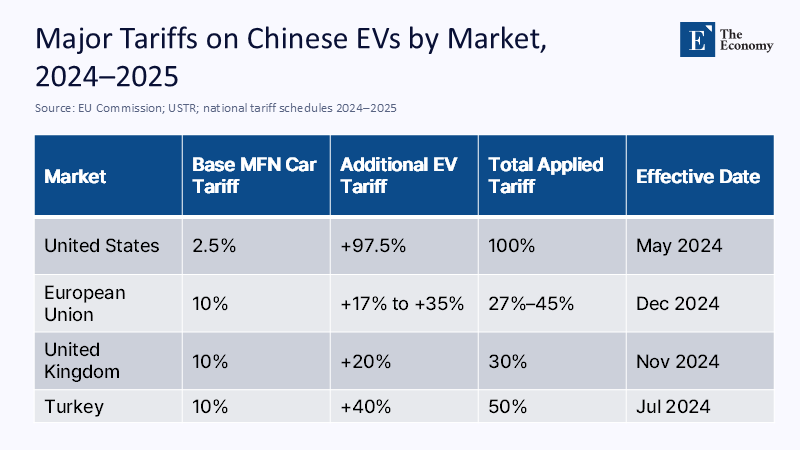

Where domestic demand has lagged, exports have filled the gap—but with rising resistance. In May 2024, the United States raised Section 301 tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles to 100%, explicitly citing overcapacity and state support. The European Union followed with definitive anti-subsidy duties—up to roughly 35% on top of the 10% MFN rate—targeting Chinese battery-electric vehicles after finding significant government support across the value chain. Chinese manufacturers have challenged the measures in court, but the policy trend is clear: tolerance for using foreign markets to absorb domestic slack is waning. Even when tactical truces pause tariff hikes, they are temporary and conditional, and bilateral exports to the United States remain far below earlier peaks.

The evidence on subsidies is no longer anecdotal. An IMF working paper using product-level data from 2009–2022 finds that Chinese subsidies raised export values and depressed imports in subsidized categories, with strong spillovers through supply-chain linkages; in sectors like autos, subsidies reduced export prices and boosted quantities. Independent analyses reach similar conclusions about the density of support instruments. This is the core of the backlash: when a domestic demand gap is diverted outward via subsidized supply, partners respond with trade remedies. For China, doubling down on an export-first strategy in this environment risks margin compression at home, serial tariff escalations abroad, and a “race to the bottom” in contested sectors. The way out is to raise internal absorption so that external markets are a complement, not a crutch.

Why Consumption-Led Growth Is Both Feasible and Necessary

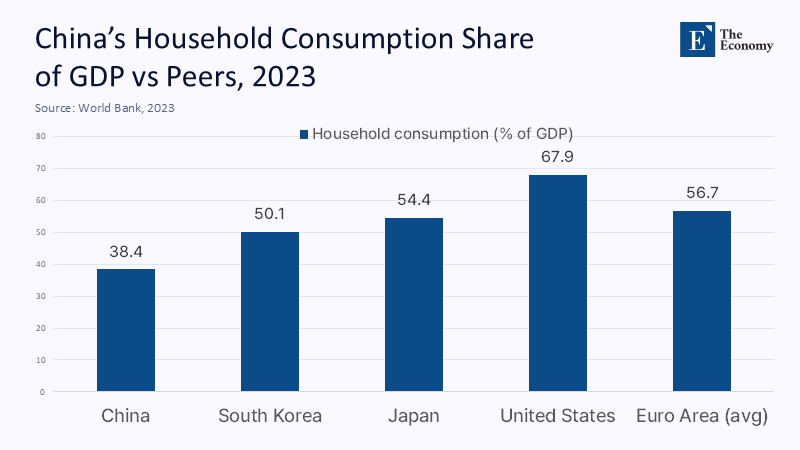

China’s household-consumption share of GDP remains unusually low by international standards—around the high-30s to about 40% in recent years—versus roughly 50% in South Korea and nearer 60% across advanced economies. World Bank series and IMF analyses point to persistently high national saving and investment shares as the flip side of under-consumption. The implication is arithmetic as much as strategic: modest increases in the household share would translate into enormous absolute demand, given China’s scale. A sustained five-percentage-point rise in household consumption as a share of GDP would add on the order of several trillion yuan annually at current levels, enough to offset meaningful export headwinds. With growth targets near 5% and inflation subdued, the macro environment can accommodate a reweighting without overheating.

Is financing a reweighting plausible? Yes—and without perpetual deficits. Beijing accelerated sovereign issuance in early 2025 and announced record ultra-long special treasury bonds to fund economic priorities. Analysts expect overall government-bond supply in 2025 to set fresh records, even as yields remain contained. In parallel, state-owned enterprises have been pushed to increase dividend remittances, and officials have signaled room to expand central borrowing while swapping and refinancing hidden local debts. Redirecting a portion of industrial subsidies and SOE dividends toward permanent transfers and social services is not just affordable; it is good macroeconomics if the goal is to reduce precautionary saving.

The Policy Mechanics: Repair Balance Sheets, Put Cash in Pockets, Finish Homes

Start where the damage was done: the household balance sheet. With prices falling and labor-market uncertainty elevated, families need certainty more than slogans. A national mortgage-relief framework for eligible owner-occupiers—rate reductions, term extensions, and the option to switch to lower-rate products without penalty—would free disposable income immediately. Because banks’ funding costs have been trending lower and the central government can provide guarantees or loss-sharing on restructured pools, system-wide margins need not be crushed. Pair that with a credible, time-bounded program to finish presold and stalled housing projects. Completion reduces the risk of mass write-downs for households and restores faith in the most crucial store of urban wealth. When the median household’s monthly outlays and asset anxieties fall, the propensity to consume rises.

Second, replace sporadic vouchers with predictable, rules-based transfers. Expand and standardize pensions and health-insurance benefits nationally, accelerate portability, and raise replacement rates for low-income cohorts. Finance the transition through a triad: higher central deficits while rates are low; re-prioritization of existing industrial support where spillovers are weak; and a mandated step-up in SOE dividend payouts to the budget. IMF and World Bank work repeatedly shows that stronger social insurance lowers precautionary saving; Rhodium Group’s 2024–2025 analysis argues that consumption constraints are structural and recommends exactly this type of fiscal reweighting toward households. The objective is permanence. When families believe the floor will hold, they stop building their own.

Fix the Transmission: Local Debt, Federalism, and Smarter Subsidies

A household-first strategy will fail if local governments cut services to meet creditors. Beijing’s debt-swap and refinancing programs should therefore be tied to service-delivery floors: provinces that restructure hidden debts with central backing commit to maintaining minimum per-capita spending on health, education, and social care. The IMF’s 2025 assessment underscores the systemic importance of bringing LGFVs under firmer budget constraints and limiting fresh off-balance-sheet borrowing. Centralizing a larger share of social-policy financing—while gradually shrinking reliance on land sales—would stabilize local budgets and allow mayors to focus on delivery rather than juggling maturities. This is fiscal federalism for resilience, not a bailout of bad bets.

On the supply side, Beijing should move from scale to quality. The EU’s definitive duties and the U.S. tariff reset are red lights for a subsidy regime that prioritizes volume over demand. A transparent rulebook for support—favoring productivity-raising investments and phasing out capacity-expanding subsidies that merely intensify price wars—would accelerate market exit of unviable producers and lift sectoral profitability. In EVs, for example, disciplined consolidation and genuine domestic demand would let leaders sustain innovation without exporting deflation. If the state wants independence in AI, chips, and biotech, the best complement is a deep, confident home market that rewards value rather than volume.

Consumption Diplomacy: Reduce Frictions by Importing More

A consumption-led pivot is not just macroeconomics; it is foreign economic policy. By committing—measurably—to import more of what Chinese households want, Beijing can defuse the politics of “overcapacity” abroad and build constituencies for stable ties. Practical steps include widening tariff-rate quotas and lowering applied tariffs on consumer-relevant goods such as higher-quality foods, medicines, personal-care items, and baby products where domestic supply is capacity-constrained. Liberalizing access for foreign providers of services—health, education, tourism, entertainment—would raise consumer welfare directly and boost services imports, a pressure valve for goods-surplus politics. When partners see their exports rise because Chinese families are spending, the logic of tariffs weakens.

This is the strategic inversion embedded in your angle. Respect in the global system comes less from flooding markets with subsidized supply than from becoming a market others are eager to serve. Japan’s post-1990 trajectory was never easy, but its shift toward a more consumption-balanced economy illustrates how high-income societies sustain demand despite aging. Korea’s path shows the constraint of a small market size; China does not share that constraint. Its scale makes a domestic-demand pivot not only necessary but powerful. If executed with credible social insurance, local-debt repair, and more innovative subsidy governance, the transition will reduce dependence on the U.S. consumer, increase leverage in trade negotiations, and lower the temperature of industrial conflict.

Anticipating the Hard Questions—and Meeting Them

Skeptics point to demographics. An aging society, they argue, cannot drive consumption. In reality, aging economies with reliable safety nets tilt consumption toward services—health care, leisure, domestic tourism—raising labor intensity and spreading demand across regions. The binding constraint is not age but insecurity. Raise pension adequacy and health-insurance credibility, and the savings rate responds. Others worry about fiscal space. Yet Beijing is already accelerating bond issuance, including ultra-long maturities, with plans for record special-treasury-bond programs in 2025. Debt sustainability hinges on the composition of spending: moving from investment subsidies that spur overcapacity to transfers that unlock private consumption can raise the economy’s effective multiplier even as headline deficits tick up.

A final objection is moral hazard: mortgage relief and LGFV swaps could invite new risk-taking. That is a design challenge, not a fatal flaw. Relief should be paired with more rigid budget constraints—hard caps on new off-balance-sheet borrowing, standardized bankruptcy procedures for developers, stronger consumer protections in presales, and public disclosure of local fiscal risks. The point is not to resurrect the old model but to smooth the transition to a new one. If China insists on solving a domestic demand gap with foreign demand, it will meet a wall of tariffs and countervailing measures again and again. If it disciplines subsidies, finishes homes, funds households, and buys more from abroad, it will turn today’s surplus into tomorrow’s stability.

Rebalancing for Power, Not Just Peace

The past four years have stripped the illusions from China’s old playbook. The property boom’s wealth effect has faded; local debts constrain services; households save because the floor feels soft. Meanwhile, state-enabled exports have crashed into a protectionist wall in the West, with EVs the emblem of a wider dispute. The correct answer is not louder industrial policy or another surge of subsidized capacity; it is a domestic social contract that puts households at the center. Finish the homes, restructure the mortgages, widen and stabilize transfers, set spending floors for local services, and import more of the quality goods and services families want. That program would shrink precautionary saving, thicken the domestic market, and lower the political temperature abroad by signaling that China is ready to consume as well as compete. It would also sharpen leverage in trade talks by reducing dependence on any single external market. The surplus was a symptom. The cure is consumption. If Beijing chooses it now, it can turn contested scale into respected leadership.

The original article was authored by the EAF editors. The English version, titled "China’s macroeconomic strategy can contain the fallout from Trump’s tariffs," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Allianz Global Investors. (2024, Oct. 4). Investing in China’s State-Owned Enterprises.

AP News. (2025, Aug. 7). China’s exports and imports picked up in July, helped by the pause in Trump’s higher tariffs.

Asia Society Policy Institute. (2025, Jun. 3). Will Ultra-Long Bonds Help Beijing Capitalize Its “New Productive Forces”?

European Commission. (2024, Dec. 12). EU imposes definitive countervailing duties on Chinese BEVs (Implementing Regulation 2024/2754).

IMF. (2024, Aug. 2). People’s Republic of China: 2024 Article IV Consultation—Press Release and Staff Report.

IMF. (2025, Apr. 30). People’s Republic of China: Financial Sector Assessment Program—Financial System Stability Assessment.

IMF (Rotunno & Ruta). (2024, Aug. 15). Trade Implications of China’s Subsidies (WP/24/180).

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2025, Jul. 16). Investment in Real Estate Development in the First Half of 2025.

People’s Bank of China. (2025, Jul. 14). Financial Statistics Report (H1 2025).

Reuters. (2025, Jan. 13). China’s exports gained momentum in December; trade surplus widened as firms front-loaded shipments.

Reuters. (2025, Jan. 21). China is not seeking a trade surplus and is willing to import more, says vice premier.

Reuters. (2025, Jun. 16). China’s home prices dip in May; weakness persists.

Reuters. (2025, Jul. 14–15). New yuan loans and June home-price readings; household loans and credit dynamics.

Reuters. (2025, Jul. 15). New-home prices fall 3.2% year-on-year; fastest drop in eight months.

Reuters. (2025, May 27). Chinese household deposits surpass 160 trillion yuan; savers cautious despite lower rates.

U.S. Trade Representative / White House. (2024, May 14; Sept. 13). Section 301 tariff increases—EVs to 100% in 2024 (Fact sheet and final determination).

World Bank. (accessed Aug. 2025). Household final consumption expenditure (% of GDP), China.

Comment