The New Vocabulary of Risk: Why Climate Has Become Central Bank Business

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In 2024, weather- and climate-related disasters inflicted about $320 billion in global economic losses, with roughly $140 billion insured, the third-costliest insured year on record. In the United States, there were 27 separate billion-dollar disasters in 2024 alone, just one shy of the record set the year before. Meanwhile, the cost of everyday mobility keeps creeping higher: motor vehicle insurance climbed 11.3% in 2024 after a 20.3% surge in 2023, and in May 2025, it was one of the single most significant contributors to the overall U.S. inflation rate. These are not abstract figures; they are the translation layer between heat maps and household budgets, between flooded streets and balance sheets. When “non-peak perils” like floods and severe convective storms now rival hurricanes in annual losses, the implication for financial stability is direct: collateral values swing, risk premia widen, and the transmission of monetary policy grows noisier. Central banks are not chasing a fashion; they are the key players in catching up with the math of a non-stationary climate.

Reframing the Core Question: From Climate as Ethics to Climate as Macroprudential Necessity

The old debate framed climate as a moral or political choice—worthy, perhaps, but tangential to the narrow mandates of price and financial stability. That framing misses how climate shocks now behave in the system. As floods, wildfires, and extreme storms increase in frequency and intensity, they do not stay in the “tail” where traditional risk models once assumed they belonged. They migrate toward the center of the distribution, eroding the reliability of collateral and the predictability of cash flows. When entire used-car markets are hit after major flood events and home insurance becomes costlier or scarcer in exposed areas, monetary policy must work through a financial sector whose pricing of risk is being rewritten in real time. Central banks, charged with keeping the pipes unclogged, must see that rewrite clearly and ensure that the banking and insurance core remains resilient.

This reframing matters now because the statistics have crossed from episodic to systemic. Five consecutive years of >$100 billion in insured catastrophe losses is not a fluke; it is an actuarial regime shift. In Europe and the Middle East, 2024 floods alone generated about $13 billion in insured losses, while globally, non-peak perils produced loss totals well above decade averages. The downstream macro-financial channels are multiplying: higher insurance premia feed through to CPI; asset impairments weaken bank capital via credit risk; and expectations of recurring losses push lenders to reprice or retreat from regions and sectors. Price stability and financial stability are being pressed by the same physics from different angles. In that world, climate ceases to be “extraneous” to central banking and instead becomes one of the core state variables shaping risk premia, lending, and, ultimately, the pass-through of policy rates.

The Numbers No Longer Hide in the Tails

Consider three concrete markers. First, NOAA counted 27 billion-dollar disasters in 2024, after a record 28 in 2023, with cumulative damages of $182.7 billion in 2024 alone. Second, Swiss Re estimates global insured losses at about $137 billion in 2024 and notes a 5–7% real growth trend in catastrophe losses over recent years. Third, U.K. motor insurers paid a record £11.7 billion in claims in 2024, with weather-related home claims also hitting records, illustrating how frequent “everyday” weather now drives large, rolling payouts. These figures are competitive with economic cycles themselves. When the insurance sector becomes a persistent amplifier of cost shocks, the central bank’s inflation and stability calculus must absorb that reality rather than wish it away.

A regional lens underscores the point. Storm Daniel’s floods in Greece in 2023 caused damage running into multiple billions of euros, with a subsequent government estimate placing the required measures at €5 billion. Only a fraction was insured, typical of significant protection gaps in Southern and Eastern Europe. When fertile plains like Thessaly—12% of Greece’s agricultural gross value added—go underwater, the hit radiates through food prices, employment, and bank exposures to SMEs and farms. Europe’s 2024 flood season then delivered another costly wave across Central Europe, compounding the message to supervisors: physical climate risks are here now, not an abstract 2050 scenario. Such realities are precisely why European authorities have integrated physical-risk modules in climate stress exercises and are pressing banks to move beyond pilot exercises to concrete risk practices across their portfolios.

How Markets Hear Central Banks

In the past two years, central bank communication has evolved from broad exhortations to more granular supervisory expectations and scenario guidance. Phase IV of the NGFS (Network for Greening the Financial System) scenarios deepened pathways for both transition and physical risk, and several authorities—including the Federal Reserve—completed pilot climate scenario analyses with large banks to map data gaps and modeling needs. Concurrently, a growing literature documents that lenders are already incorporating climate risk into pricing, with higher credit spreads or rates for “brown” exposures, particularly in periods of tighter financial conditions. This is not “climate activism”; it is the ordinary operation of risk-based finance, sharpened by supervisory clarity.

Communication has market consequences beyond bank balance sheets. Sustainable debt issuance crossed the $1 trillion mark again in 2024, with climate-aligned issuance tallying record volumes even as policy uncertainty has weighed on 2025 year-to-date labels. The signaling channel runs two ways: when supervisors underline physical-risk management, it boosts the case for adaptation finance (flood defenses, resilient grids), while credible transition pathways support green investment flows. Communication, in other words, helps coordinate expectations—one of the few “low-cost” tools that can shift risk assessment at scale without overstepping legal mandates. The point is not to pick winners but to reduce the odds that climate blind spots metastasize into correlated asset shocks that central banks would later have to clean up at far greater expense.

What Better Models Make Possible

The modeling frontier has moved. After 2008 exposed the fragility of Gaussian assumptions, risk practitioners embraced fat tails; today, climate risk work goes further, embedding jump processes and extreme-value logic directly into credit and market risk models. The need for new modeling approaches is urgent. Recent central-bank-adjacent research extends the one-factor Vasicek framework to include physical risk components, enabling portfolio-level loss projections that incorporate regional hazard intensification. Other studies deploy jump-diffusion approaches to capture transition shocks—tightening standards or abrupt technology shifts—that can reprice carbon-intensive assets. These are not exotic toys; they are the next-generation equivalents of the models that once legitimized derivatives and, later, stress testing.

Methodologically, this shift matters because it aligns finance with the statistical nature of the underlying hazard. Floods, heatwaves, and convective storms are best treated as compound, non-stationary perils whose arrival rates and severities evolve with warming and urban exposure. Incorporating Poisson-type jumps for event incidence and generalized extreme value or peaks-over-threshold methods for tails yields loss distributions that match observed claims data far better than smooth diffusions. When those distributions feed into bank IRB credit models, they change optimal capital buffers, loan-to-value haircuts, and geographic concentration limits. The upshot: better models allow supervisors to be humble about point estimates while still being decisive about prudence, moving the system toward resilience rather than precision theater.

Policy Translation: From Speech to Balance Sheet

If the goal is to safeguard price and financial stability, then climate belongs in three operational buckets. First, micro-prudential supervision: clarifying expectations for board-level oversight, data architecture, and integration of physical and transition risks in ICAAP/ILAAP, with disclosure frameworks that are proportionate and, where possible, globally interoperable. The latest Basel initiative favors a voluntary disclosure template, leaving enforcement to jurisdictions; that puts more onus on regional supervisors like the ECB and BoE, who have been publishing good-practice compendia and scenario design notes. Second, macro-prudential policy: hardwiring climate into systemic risk surveillance, sectoral buffers, and concentration add-ons where exposures to climate-sensitive sectors are material. Third, collateral and facilities: calibrating haircuts on climate-vulnerable securities and designing liquidity lines that anticipate post-disaster funding stresses without socializing underwriting failures.

An urgent next step is to build a “Climate Financial Conditions Index” (C-FCI) to complement conventional FCIs. Such an index would synthesize spreads for catastrophe bonds and reinsurance, insurance premium inflation, flood-zone mortgage rates, and drought-exposed commodity financing, alongside nowcasts of hazard intensity. Central banks already maintain dashboards of credit, equity, and volatility indicators; adding a climate strand would systematize what is now implicit in ad-hoc stress memos. On the supervisory side, embedding region-specific hazard-intensification maps into collateral frameworks can mitigate the silent build-up of wrong-way risk—where lenders depend on collateral whose value is most likely to vanish precisely when liquidity is needed. None of this requires picking climate winners; it requires pricing climate reality and ensuring the financial sector can survive it.

Where Monetary Policy Meets Hydrology

Climate shocks do not only threaten banks; they also filter into inflation through food, energy, insurance, and transport. The ECB recently warned that drought alone could reduce euro-area output sharply, with specific sectors and geographies carrying disproportionate risk. In the U.S., public data show that motor vehicle insurance has become a notable, recurring contributor to headline inflation—an underappreciated channel through which physical risk transmits to the price index that anchors monetary debates. Including hydrological and heat-stress nowcasts in forecasting models is not a futurist flourish; it is a necessary adjustment to the reality that water levels, wildfire smoke, and storm clusters move prices. When persistent shocks obscure underlying disinflationary trends, clearer decomposition helps keep policy appropriately calibrated.

A practical way forward is to formalize three bridging tools. First, a climate-augmented Phillips-curve term that captures the short-run effect of extreme weather on food and energy volatility, improving the separation of signal from noise. Second, an insurance-cost pass-through module in core inflation models, given the sustained elevation of claim severity and repair-cost inflation after extreme events. Third, targeted liaison programs with reinsurers and catastrophe modelers to feed scenario-consistent expectations into policy deliberations. Central banks routinely consult a wide range of market intelligence, including climate-risk specialists, to help anticipate the pass-through dynamics that standard macro models still underweight.

Anticipating the Critiques—and Answering Them

Critique one is politicization: that climate is a legislative domain and monetary authorities should stay out. The answer is institutional modesty paired with risk realism. Legal analyses by international financial institutions consistently emphasize that integrating climate-related financial risks is within supervisory remits when those risks threaten safety and soundness. Supervisors need not—and should not—set emissions caps; they must ensure banks can withstand known shocks and foreseeable concentrations. That is the orthodoxy of prudence, not mission creep.

Critique two is model uncertainty: the claim that data are poor and hazard projections are noisy. True—but the appropriate response to uncertainty in tail risks is not paralysis; it is thicker buffers and scenario ranges that map policy to resilience bands rather than false precision. The IMF’s latest stability assessments warn that rising uncertainty increases the likelihood of adverse shocks, and the NGFS Phase IV scenarios were designed precisely to explore divergent futures across physical and transition pathways. When multiple reputable lenses converge on the same direction of travel—higher tail risk, larger losses, rising premia—supervisors are justified in acting on the sign, even as they debate the exact magnitude.

Critique three is market substitution: if central banks tighten oversight, won’t risks migrate to insurers or non-bank intermediaries? To an extent, yes—which is why coordination matters. Insurance strains are already visible in premium dynamics and coverage withdrawals in hazard-exposed areas, and supervisors of insurers have issued fresh guidance on climate-risk oversight. Macro-prudential bodies should therefore expand system-wide scenario exercises to include insurers and key non-bank lenders, recognizing that adaptation finance and catastrophe-risk transfer will increasingly sit outside traditional banks. The goal is not to fence risk within banks but to keep it transparent, priced, and, where possible, diversified across entities that understand it.

A Practical Agenda for Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers

Educators can lead by updating curricula to reflect the new statistical grammar of risk—teaching jump-diffusion processes, extreme-value methods, and hazard-linked credit modeling alongside traditional term-structure and VAR material. Students entering banking, insurance, and public policy should be conversant in NGFS scenarios and able to audit a climate-risk workflow from data ingestion to portfolio impact. Administrators—especially in higher education and local government—should treat campus and municipal adaptation as balance-sheet management, not just sustainability. Flood-proofing, heat resilience, and microgrid investments are cash-flow stabilizers and insurance premia dampeners; they deserve the same financial rigor applied to endowment allocation or debt issuance.

Policymakers can accelerate three actionable reforms. First, mandate public flood, fire, and heat risk maps at the parcel or facility level, with open APIs, to cut data asymmetries that hamper lenders and buyers alike. Second, support parametric insurance mechanisms and risk-pooling at regional scales to reduce protection gaps where private insurance is withdrawing. Third, encourage the development of a C-FCI and hazard-aware collateral frameworks through the systemic-risk councils that already convene central banks, finance ministries, and market regulators. The task is not to green finance by fiat but to harden finance against the physics already in motion. The alternative is to keep socializing private risk after the fact—expensive, inequitable, and, ultimately, self-defeating.

The Cost of Waiting Is Now Accruing Interest

The figure that should concentrate minds is not just the $320 billion in 2024 global disaster losses or the 27 billion-dollar events in the U.S.; it is the steady, structural rise in insured losses and the way those losses are colonizing everyday prices—from car insurance to mortgages in floodplains. When the hazard ceases to be rare, our models, our supervision, and our monetary analysis must update. We are past the point where climate can be cordoned off as a values debate and kept outside the central bank’s door. The path forward is clear enough: communicate risks, model them with tools that fit the data, embed them in prudential practice, and coordinate across banks, insurers, and markets so that adaptation finance rises to meet physical exposure. The longer we wait, the more compounding works against us—through higher premia, wider risk spreads, and costlier shocks. The bill is already arriving. The only question is whether we pay for resilience now or keep paying interest on avoidable fragility.

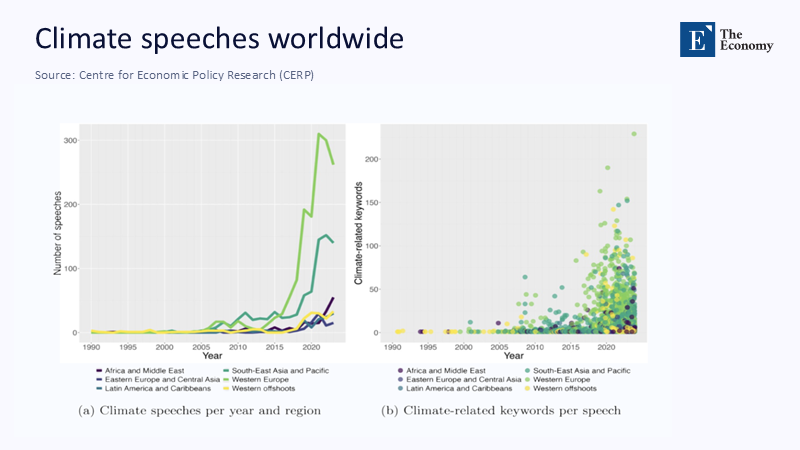

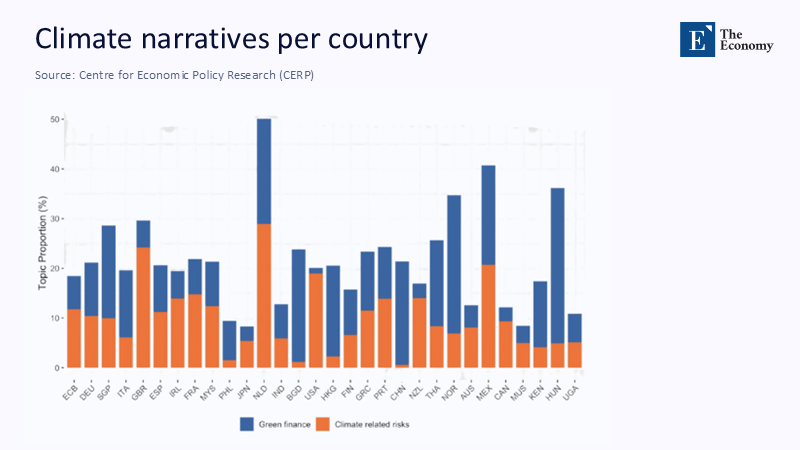

The original article was authored by Emanuele Campiglio, an Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Bologna, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "How central bankers speak about climate and what this means for financial markets," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Aon (2025). 2025 Climate and Catastrophe Insight.

Bank of England (2024, Apr. 17). Measuring climate-related financial risks using scenario analysis.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2025, Feb. 12). Measuring Price Change in the CPI: Motor vehicle insurance.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2025). Consumer Price Index: 2024 in review.

European Central Bank (2024, Nov. 19). Transition risk losses alone unlikely to threaten EU financial stability, “Fit-for-55” climate stress test shows.

European Central Bank (2025, Jul. 11). Banks have made good progress in managing climate and nature risks – and must continue.

Financial Times (2025, Jun.). Droughts are major threat to Eurozone economy, warns ECB.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (2025, Apr.). Application Paper on the supervision of climate-related risks in the insurance sector.

Munich Re (2025, Jan. 9). Natural disaster figures for 2024.

National Centers for Environmental Information, NOAA (2025). U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Time Series.

Natixis (2025, Apr. 14). Sustainable Debt in Focus: 2024 Summary and 2025 Outlook.

Network for Greening the Financial System (2024). NGFS Climate Scenarios for central banks and supervisors – Phase IV.

Swiss Re Institute (2024, Dec. 5). Hurricanes, severe thunderstorms and floods drive insured losses…

Swiss Re Institute (2025, Apr. 29). sigma 1/2025: Natural catastrophes – insured losses on a new level.

U.K. Association of British Insurers (2025, May 13). Quarterly motor claims hit record high.

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Federal Insurance Office (2025, Jan. 17). Report on the personal auto insurance market.

U.S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transportation Statistics (2025, July). Transportation CPI – May 2025.

Bank for International Settlements (2025). Pozdyshev, V. et al., Incorporating physical climate risks into banks’ credit risk models (BIS Working Paper No. 1274).

Campiglio, E., et al. (2025). Central bank communication and climate change. European Economic Review (in press).

New York Fed (2024). Brunetti, C., et al. Climate-Related Financial Stability Risks for the United States. Staff Report.

World Bank (2025, Feb.). Labeled Sustainable Bonds Market Update (Issue 10).