Beyond the 2025 Scoreboard: Southeast Asia as the World’s Decarbonisation Exchange

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

By Feb. 10, 2025, more than 90% of countries had missed the UN deadline to submit their next-round climate plans. The drumbeat headline was a failure. Yet an equally important fact sat in the footnotes: the Paris Agreement’s Article 6 now lets countries count emissions cuts achieved abroad, provided they are authorized and validated with “corresponding adjustments.” In other words, the scoreboard is no longer confined to domestic stadiums. As Chinese and Japanese capital surge into Southeast Asian renewables and grids—from record Belt and Road clean-energy engagement in 2024 to Japan’s Joint Crediting Mechanism—tonnes reduced in ASEAN can, under the rules, be credited to investor countries’ ledgers. That reframes the region’s role entirely. Even with missed targets, Southeast Asia is becoming the place where mitigation is made, financed, and—crucially—accounted for. The question for 2025 isn’t simply who filed a plan on time; it’s who is building the institutions to turn every megawatt installed into high-integrity, internationally transferable climate results.

Reframing the Question: From Target Compliance to Transnational Mitigation

The old way to grade climate progress was domestic: set a goal, tally local emissions, and compare the two. That frame makes 2025 look bleak. The better lens is transactional and transnational. Article 6 enables “internationally transferred mitigation outcomes” (ITMOs) where one country finances mitigation in another, and—after both parties authorize and adjust their inventories—the buyer can count the reduction toward its nationally determined contribution. Japan’s Joint Crediting Mechanism goes further, operationalizing this through standardized bilateral crediting and explicitly stating that credits will be used toward Japan’s NDC. Put plainly, ASEAN can export decarbonisation, not just equipment. For countries that missed the deadline, this architecture doesn’t excuse inaction; it shows where action is happening and how it gets counted—if the plumbing is in place.

Policy salience follows immediately. If Southeast Asia becomes the preferred venue for high-integrity, corresponding-adjusted credits, the region’s leverage over capital costs, technology choice, and industrial location rises. That is why investor governments and firms care less about whether ASEAN as a whole hits an aspirational 2025 energy mix target and more about whether the region can originate Article 6-eligible projects at scale with credible monitoring, reporting, and verification. Translating “tipping points” into “transfer points” focuses ministries on registries, bilateral authorizations, grid unlocks, and data transparency—prerequisites to convert physical projects into recognized units. As NDC 3.0 plans roll in late, countries that show a pipeline of authorized mitigation outcomes will still attract finance; those that rely on promises without accounting infrastructure will not. This is the real hinge of 2025.

The Data Since 2023: Progress, Gaps, and the Real Baseline

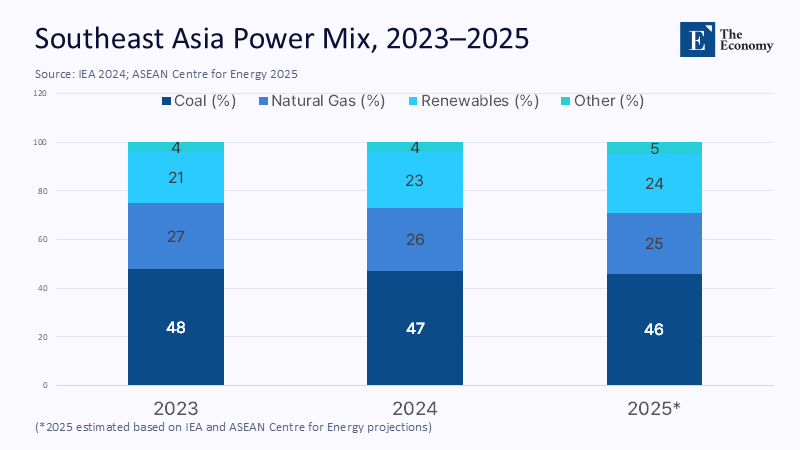

The baseline is hard. In 2023, fossil fuels supplied roughly three-quarters of ASEAN electricity, and coal alone provided nearly half; in Indonesia, two-thirds of incremental demand was met by coal. Vietnam’s power-hungry industrial boom pushed thermal coal imports up by more than 30% in 2024, and coal produced about half of its electricity. The International Energy Agency’s 2024 outlook shows coal still generating roughly half the region’s power, responsible for four-fifths of power-sector emissions. At the same time, ASEAN’s own energy body projects the region will miss its 2025 target of 23% renewables in total primary energy supply, likely landing near 19.6%. These are not failure stories so much as honest constraints: fast-growing demand, infrastructure lag, and weak grids.

Investment still lags need. Despite Southeast Asia accounting for about 5% of global energy demand, the region drew only around 2% of global clean-energy investment recently, with estimates that it must mobilize on the order of $190 billion annually by 2030—roughly five times current levels—to hit stated goals. Yet costs tilt in the region’s favor. IRENA’s 2024 cost data place global utility-scale solar at roughly $0.043/kWh and onshore wind at about $0.034/kWh; ASEAN analysis shows solar LCOEs now competitive with or below new coal in Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, and Malaysia. Demand is rising, costs are falling, and grid bottlenecks—not technology—are the binding constraint. Recognizing that picture clarifies the task: finance grids and bankable projects, then convert their outputs into Article 6 units that draw still more capital.

Why Capital Is Coming: Counting Emissions Cuts Abroad

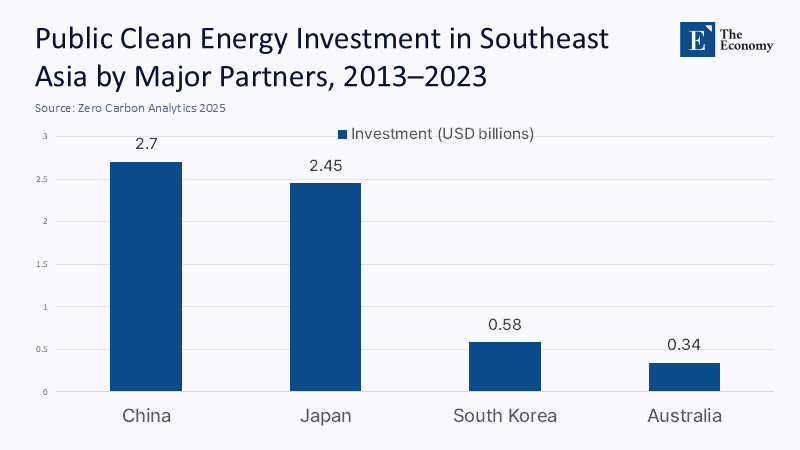

The strategic investors are not shy. Zero Carbon Analytics reports that, over 2013–2023, China was Southeast Asia’s most significant public funder of clean energy ($2.45 billion) and South Korea third (~$0.58 billion). Trade in clean technologies is even more China-skewed, with substantial flows of batteries, modules, and components into ASEAN. Meanwhile, Chinese outbound cleantech investment has hit unprecedented levels since 2023, catalyzed by tariff headwinds in the West and the search for new manufacturing hubs in Thailand and Indonesia. The motive isn’t charity. It’s supply-chain positioning, market access, and—in Japan’s case—a direct line to NDC accounting via JCM credits. That alignment of industrial policy and climate accounting is precisely what makes Southeast Asia a magnet even when global politics wobble.

For Japan, the link to counting is explicit. Government documents state that credits acquired under JCM “will be used towards the achievement of Japan’s NDC,” with the partner country also retaining a share. South Korea is moving in a similar direction: official ETS documentation references the government’s aim to use up to 37.5 million international credits toward its 2030 target, with active efforts underway in 2025 to revamp Article 6 procurement. Add the broader picture—COP29 outcomes that finally operationalized Article 6 rules—and the business case tightens. Financing a wind fleet in Vietnam or rooftop solar in Indonesia can deliver local power and a transferable climate result. When the accounting aligns, capital follows.

Building the Regional Machine: Carbon Accounting, Grids, and Guarantees

To convert projects into internationally recognized mitigation outcomes, ASEAN needs a coherent “machine”: legal authorizations, registries, MRV systems, and bilateral templates that minimize friction. The 2025 legal and market guidance is finally there—Article 6.2 rules on authorization, tracking, and corresponding adjustments—and Asia-Pacific price signals are emerging above voluntary-market levels. A practical next step is a regional Article 6 facility housed with or alongside the ASEAN Centre for Energy and linked to the ASEAN Taxonomy Board: a single window to pre-screen methodologies, standardize host-country letters of authorization, and publish pipelines to de-risk private finance. Blend ADB/ACGF concessional tranches with commercial capital, tie disbursements to MRV milestones, and let investor governments contract for delivered, adjusted tonnes. This is financeable policy architecture, not a new target.

Grids are the other half of the machine. The Lao–Thailand–Malaysia–Singapore Power Integration Project (LTMS-PIP) is small in volume but large in symbolism: the first four-country power trade in ASEAN. Phase-two announcements would double traded capacity from 100 MW to 200 MW, and technical assessments point to an eventual ceiling around 300 MW on current infrastructure. By mid-2025, Singapore had imported over 120 GWh of clean power year-to-date, with total LTMS trade topping a quarter-terawatt hour since launch. Singapore’s broader target—to import up to 6 GW of low-carbon electricity by 2035—turns cross-border flows from pilot to policy. Every added interconnector reduces balancing costs, enables more wind and solar, and, critically, simplifies issuance of robust cross-border mitigation outcomes.

Risk Management in a Recalibrating World: Keeping the Money Flowing

Two near-term risks could sap momentum. First, the missed NDC deadline invites target “re-baselining,” which delays execution. Second, geopolitical shifts have already pulled a material source of concessional capital out of the region; reporting in mid-2025 pointed to a US withdrawal from key transition partnerships and a broader retrenchment in climate finance. ASEAN institutions see the risk clearly, urging diversification of funding lines and more structured regional mechanisms. The response should not be another communiqué. It should be a term sheet: standardized PPAs and wheeling rules, transparent curtailment compensation, and host-country authorizations baked into procurement. That way, even if specific donors pause, bankable projects keep the pipeline primed.

Second, the debt mix matters. Indonesia and Vietnam’s JETP blueprints skew heavily toward loans—on the order of 96–97%—raising obvious concerns about fiscal headroom and crowd-out. Rather than treating concessional scarcity as fatal, ASEAN can use Article 6 to pull private capital in on the back of revenue certainty. Carbon contracts-for-difference, underwritten by blended facilities, would top up delivered ITMO prices to a pre-agreed floor, stabilizing cash flows for developers. Early price signals in Asia’s nascent Article 6 market suggest this is feasible—and far cheaper than sovereign guarantees. Pair that with targeted grid investments that Ember and others identify as the key unlock, and the region can transform a 2025 “missed deadline” narrative into a 2026–2028 commissioning wave that is measurable and monetizable.

The Metrics That Matter Now: How Much, How Fast, and Where It Counts

If NDC 2025 was never feasible for many economies, the pragmatic response is not resignation but re-scoring. Three metrics should dominate. First, volume: terawatt hours of clean generation and verified tonnes issued with corresponding adjustments. Second, velocity: permitting-to-COD timelines, grid connection queues, and interconnection build-out—because the cheapest megawatt is stranded if it cannot flow. Third, value: unit costs of delivered renewable power and the realized price of ITMOs under signed bilateral agreements. None of these depend on an arbitrary deadline; all of them rely on institutions that ASEAN can build. As costs for solar and wind remain globally competitive and as Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam refine cross-border trade and domestic procurement, the pathway is visible. What was once a regional aspiration—exporting electrons and mitigation—now has rulebooks and price curves.

As investor countries retool their industrial strategies in response to tariffs and supply-chain realignment, Southeast Asia’s comparative advantage strengthens. From geothermal know-how financed by Japan to battery component exports from South Korea and module factories backed by China, the ingredients for a manufacturing-to-deployment flywheel are already present. What converts those inputs into a durable advantage is policy plumbing: a common registry spine for Article 6 credits, standardized host-country authorizations, time-bound grid connection rules, and a regional approach to balancing that lets Laos’ hydro firm up Vietnam’s wind and Malaysia’s solar for delivery to Singapore. That is how the region moves from “tipping point” to “transmission point,” from target talk to tradeable tonnes.

Stop Grading, Start Accounting

The most revealing statistic of 2025 is not the share of countries that missed a filing date; it is the share of global clean-energy supply chains and mitigation finance now routing through Southeast Asia. Coal still weighs on the mix, yes. But the cost curves are favorable, the interconnectors are multiplying, and the rules to count reductions abroad are finally live. Japan has shown how to translate projects into NDC-counting credits. South Korea is building its purchasing machinery. China’s manufacturers and investors are saturating the region’s value chains. If policymakers in ASEAN take the following administrative steps—codifying Article 6 authorizations, publishing pipelines, guaranteeing grid access, and standardizing contracts—capital will do the rest. The ambition for 2025 was never realistic. The ambition for 2026–2030 can be: measure how much is built, ensure it counts, and turn Southeast Asia into a decarbonisation exchange that lifts regional development while helping the world keep its climate ledger honest.

The original article was authored by Irvan Tengku Harja, the Research Lead and Program Manager for Just Energy Transition and Climate Action at The Habibie Center, Jakarta. The English version, titled "Southeast Asia’s green transition at a tipping point?" was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Asia Society. (2024). China–Southeast Asia Clean Energy Cooperation (report).

ASEAN Centre for Energy. (2025, Feb.). ASEAN Energy in 2025: Key Insights.

Argus Media. (2024, Sept. 20). SE Asian power grid phase 2 to double traded capacity.

Argus Media. (2025, May 15). Grids key to boosting SE Asia’s renewable power: Ember.

BloombergNEF. (2025, Apr. 9). Solar and batteries can meet Malaysia’s demand… (insight page).

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. (2025, Jun. 4). China is Southeast Asia’s biggest public funder… (summary of ZCA).

Carbon Market Institute. (2024, Dec. 4). International Carbon Market Update Q3 2024.

Climate Action Network. (2025, Feb. 11). Over 90% of countries fail to submit new NDCs by deadline.

DLA Piper. (2025, Apr. 25). All eyes on carbon markets amid belated progress and domestic challenges.

East Asia Forum. (2025, Aug. 9). Southeast Asia’s green transition at a tipping point.

Ember. (2024). ASEAN’s clean power pathways: Power sector 2023.

Energy Market Authority (Singapore). (2024, Sept. 21). Singapore doubles power import capacity under LTMS-PIP (Phase 2).

Financial Times. (2025, July). US withdrawal leaves energy transition funding gap in south-east Asia.

Global China Initiative, Boston University. (2025, Feb. 27). BRI Investment Report 2024.

ICAP. (2025). Korea Emissions Trading System (K-ETS) factsheet (PDF).

IEA. (2024). Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2024 (Executive summary & PDF).

IRENA. (2025, Jul.). Renewable power generation costs in 2024 (DG statements and summaries).

MOFA, Government of Japan. (2025, May 28). Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM).

METI (Japan). (2024, May). Recent Developments of the JCM (PDF).

OPIS. (2025, Mar. 19). Article 6 carbon market takes shape in Asia Pacific.

Reuters. (2025, Feb. 10). Most countries miss UN deadline for new climate targets.

Reuters. (2025, Jun. 27). Singapore’s renewables usage hits record high as imports, solar output rise.

UN ESCAP. (2023). LTMS-PIP overview (PDF).

UNFCCC. (2024). NDC Synthesis Report (2024 edition).

UNFCCC. (2025). NDC 3.0 page & guidance.

Zero Carbon Analytics. (2025). The race to invest in Southeast Asia’s green economy.

Comment