Tariffs, Energy, and the End of German “Premium” at Home: Why Europe’s Auto Jobs Will Follow the Production

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

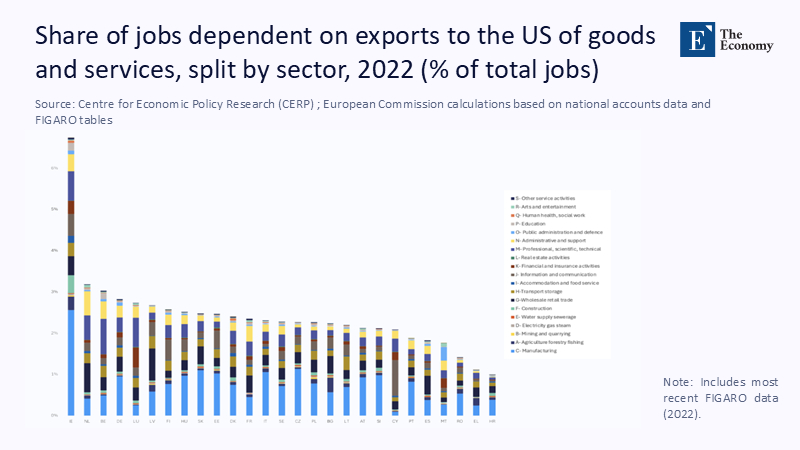

Five point two million European jobs depend on exports to the United States. That headline figure—often used to argue for caution in transatlantic trade spats—obscures a sharper reality: job risk is no longer spread evenly across sectors but piled high in a few premium, energy-intensive strongholds, with Germany’s carmakers at the core. Since April–July 2025, U.S. policy has shifted from threat to implementation limbo: tariffs on EU autos and parts were raised to 27.5% and were slated to settle at 15% under a July framework, but enforcement is still pending; exporters continue to ship under the higher rate. Even a “relief” of 15% is six times the pre-2025 2.5% passenger-car duty. Combine that with Germany’s chronically elevated industrial power costs since the Russia–Ukraine energy shock, and the premium business model becomes arithmetic that no marketing can fix. The outcome is predictable: production moves, or margins do. If margins move first, jobs will follow.

From Job Counts to Premium Erosion

The standard frame treats transatlantic tariffs as a diffuse macro shock: some exports fall, some jobs are reallocated, and the single market absorbs the rest. That frame fails to capture how today’s policy mix attacks the premium pricing wedge itself—the hallmark of German automakers. The 'premium pricing wedge' refers to the higher prices that premium brands can command due to their brand power and the quality of their products. In the U.S. market, premium brands lean on higher average transaction prices (ATPs), low incentives, and a customer base that tolerates price increases. But tariffs act as a lump-sum surcharge precisely at the point of sale, while elevated European input costs erode the margin cushion upstream. The squeeze is not symmetrical; it focuses on firms that still ship finished vehicles from Europe and source energy-heavy components at EU prices. In effect, the “premium” is being taxed twice—once at the border, once on the bill for electricity.

Reframing the debate means acknowledging that the relevant unit is not the EU export job in the abstract; it is the premium badge in a tariffed market facing structurally higher costs. The 'cost stack' refers to the total costs incurred in the production and export of a vehicle, including labor, materials, and energy. The question is not whether EU employment linked to U.S. trade is at risk—of course it is—but whether the premium segment can remain premium if the cost stack climbs faster than brand power can stretch. The answer depends on geography. If production for the U.S. market happens in the U.S., with local batteries and North American final assembly, the premium survives. If not, prices must rise or profits must fall. Either route hollows the European footprint.

The New Math: Tariffs, Energy, and Margin Compression

Start with the border. U.S. average transaction prices for new vehicles hovered around $48,900 this summer. At the same time, the luxury segments sit much higher—$58,000 for mainstream luxury cars, $75,000 for luxury mid-size SUVs, and over $100,000 for luxury full-size SUVs. If a German marque ships a $70,000 SUV and faces a 27.5% import duty rather than the pre-2025 2.5%, the tariff uplift jumps from $1,750 to $19,250—an order-of-magnitude change that no quarterly incentive plan can consistently absorb. Even if the July framework’s 15% level is eventually enforced, that still implies $10,500 at the border. With U.S. consumers already paying near-record MSRPs, price resistance rises, pushing brands toward margin give-backs or production relocation to qualify for U.S. credits and avoid the duty. The economics do not favor staying put in Europe to serve the U.S. market.

Now add energy. German industry’s electricity costs surged after the 2022 gas shock and remain structurally higher than U.S. levels despite a wholesale price retreat in 2023–2024. Germany’s auto association has warned repeatedly that firms pay up to three times competitors’ power prices; proposals for an industrial power price have met political and legal headwinds. Producer-price data show only partial normalization, and Germany’s policymakers and institutes concede competitiveness erosion. This is not a temporary spike that a pricing team can ride out; it is a shift in the cost baseline. When border duties meet expensive electrons, even well-managed OEMs with historically strong EBIT margins see compression. That is already visible in company guidance and rating-agency outlooks for 2025.

Where to Build: The Relocation Imperative

U.S. policy now rewards local production with tax credits that hinge on North American final assembly and increasingly domestic or allied sourcing of critical minerals and battery components. Treasury’s final rules lock in a two-part $7,500 clean-vehicle credit and progressively tighten “foreign entity of concern” restrictions through 2025–2027. Even when Treasury softens timing on graphite or clarifies tracing, the signal is unmistakable: put the plant—and the battery supply chain—in North America or price at a disadvantage. For any OEM selling meaningful volumes in the U.S., the path of least resistance is to localize. The tax code has become an industrial strategy.

Asia’s legacy brands have already moved. Toyota’s North Carolina battery complex is a $13.9 billion anchor with production starting in 2025; Honda and LG are commissioning a 40 GWh Ohio plant to feed local assembly; Hyundai-Kia’s Georgia “Metaplant” targets 300,000 vehicles annually, with hybrids queued and three-row EVs entering production windows. These are not press releases in search of markets; they are the necessary complement to tariff volatility and credit rules. German brands with deep U.S. footprints (e.g., existing South Carolina or Alabama plants) are better positioned, but that still leaves high-margin models and engines historically “Made in Germany.” To defend the premium, those models either move, get localized content rapidly, or cede share to localized rivals. In that calculus, Southeast Asia becomes a cost-competitive option for global exports, but for the U.S. specifically, North America is the rational destination.

What It Means for Workers—and Where the Jobs Go

The distributional map is already shifting. German exports to the U.S. have fallen through mid-2025, with automotive shipments taking a disproportionate hit as companies race, pause, and reroute amid tariff uncertainty. Germany’s broader industrial output has stumbled back toward 2020 levels, and business-climate indicators in energy-intensive sectors remain weak. Forecasts commissioned by industry associations warn of six-figure job losses across the decade as the sector restructures—independent of any single tariff episode—mainly due to competitiveness strains and the electric transition’s different labor profile. The 'electric transition's different labor profile' refers to the changing skill requirements in the industry as it shifts towards electric vehicles, which may lead to job losses in certain areas and the creation of new roles in others. A tariff shock layered atop that structural shift accelerates the timing of layoffs rather than changing their direction.

Unions have read the same tea leaves. European and national labor organizations are calling for emergency measures to keep production and skilled jobs in the EU after the July deal. Their fear is not hypothetical: when high-cost plants face rising import barriers into their key external market, consolidation and relocation follow. Nissan’s earlier decision to shutter Barcelona remains a cautionary tale; today, even without mass closures, the gradual offshoring of model lines, battery packs, and drivetrains can hollow out headcounts. If policy does nothing, the long tail of “quiet” deindustrialization—supplier by supplier, shift by shift—will do the rest.

Policy That Matches the Shock

The policy mistake would be to chase every tariff twist with ad hoc subsidies. Instead, Europe should match the nature of the shock with measures that permanently reduce the cost baseline of producing in the EU. That starts with industrial power pricing. A time-bound, rules-based mechanism to bridge the gap between EU wholesale rates and U.S. industrial tariffs—financed transparently and sunset-dated—would stabilize investment while expanded renewables and grids bring structural relief. Allowing long-term power-purchase agreements at scale, coupled with speedier permitting and connections, moves electricity from a risk to a hedge. The goal is not an artificial “Germany discount,” but a credible glide path to internationally competitive power costs.

Trade strategy must do more than react. The July framework signals détente, but its very ambiguity—announced rates without implementing orders—creates costly uncertainty. The Commission should seek automaticity: if agreed tariff reductions are not operational by a fixed date, counter-measures snap in, or adjustment support is released for exposed regions and suppliers. That would align incentives without escalating. In parallel, the EU’s industrial policy should target capabilities tied to the premium wedge: high-end components, power electronics, and software. Replace across-the-board grants with scale-up finance and public procurement for EU-made subsystems, so that even when final assembly globalizes, the value chain binding to Europe deepens.

Anticipating the Objections—and Why They Don’t Change the Trajectory

One counterargument is that tariffs will settle at 15% and become a cost of doing business, easily passed on to wealthier buyers. That understates the math. A 15% ad valorem on a $70,000 premium SUV is still $10,500 at the border; even with modest markdowns from incentives, the brand either eats points of margin or risks crossing price thresholds that nudge buyers to locally built alternatives with access to the $7,500 credit. A market accustomed to premium will tolerate some pain, but elasticity is not zero, and U.S. ATPs have already climbed near historical highs, leaving less headroom. The result is a slow bleed of U.S. share unless localization accelerates.

Another objection points to falling wholesale electricity prices in 2024 and selective months of producer-price relief as signs that the energy story is behind us. Wholesale declines are real, but the relevant benchmark for investors is expected all-in industrial power cost over a plant’s life. Germany’s power system still faces elevated grid and levies, infrastructure bottlenecks, and volatility from the transition. Industry groups, economic institutes, and international reviews converge on the same conclusion: absent structural fixes, Germany’s price wedge versus the U.S. persists. That wedge does not imply doom; it simply means that for U.S. sales, local production is the dominant strategy unless policy narrows the gap. In practical terms, the plant goes where the tariff and energy math work, and downstream jobs follow assembly lines.

What Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers Should Do Now

For universities and vocational institutions, the pivot is from generic “automotive” training to location-specific skills bundles. In Central Europe and Germany, curricula should emphasize high-precision components, power electronics, software integration, and battery pack engineering—parts of the stack likely to remain or even grow in Europe if policymakers support them. Transatlantic partnerships can pair EU programs with U.S. plants for dual-site apprenticeships, recognizing that some graduates will spend early careers in Georgia, Kentucky, or Ohio, not Baden-Württemberg. That is not defeatist; it is placement realism. Departments should invest in flexible learning modules that allow workers from shrinking European assembly operations to reskill into supplier roles, energy-systems maintenance, or grid-connected manufacturing.

Administrators in regional governments must plan as if partial relocation is a baseline, not a tail risk. That means proactive transition funds for suppliers, local PPA aggregators to deliver cheaper green power to industrial parks, and one-stop permitting offices that cut months off upgrades. At the national level, ministries should publish tariff-exposure maps by NACE code and region and tie them to automatic supports triggered when trade policy moves. Critically, every euro spent should have a path to structural cost reduction: grid reinforcement, storage, better market design—not open-ended operating subsidies. Europe cannot subsidize its way out of a cost disadvantage; it can reform and build its way out.

The Next Five Years for German “Premium”

Take a sober look at company numbers. BMW, Mercedes, and Volkswagen entered 2025 with automotive margins in the mid-single to high-single digits and explicit warnings that tariffs could trim 100–150 basis points. That is before any sustained price war in China or a cyclical slowdown. Tariffs that are six times the old rate—even if “only” 15%—do not vanish into marketing budgets. Nor do electricity bills politely return to 2019. Boards will do the rational thing: they will protect the premium by moving the point of taxation and energy risk. In practice, that means locking in U.S. content for U.S. sales and, where appropriate, leveraging Southeast Asia for cost-sensitive global models. What remains in Germany must be defended by a policy that cuts long-run costs and doubles down on high-value components rather than final assembly at any price.

Five Years to Save the Premium Badge

A single statistic framed this column: 5.2 million EU jobs hinge on U.S. exports. The number matters, but the issues of composition matter more. Tariffs aimed squarely at finished autos and parts, layered atop Europe’s energy cost wedge, threaten not just volumes but the logic of “premium made in Europe” for the U.S. buyer. If the July framework’s 15% rate eventually lands, it will be less destructive than 27.5%, but still incompatible with a model that assumes brand strength can always outrun arithmetic. The policy implication is ruthless clarity. Localize U.S.-bound production or accept a slow bleed of margin and employment. For Europe’s leaders, the correct response is not retaliation theatre but structural repair: cheaper industrial power, faster grids, smarter permits, and targeted scale-up finance for the components that anchor value at home. The badge survives if the math does. For now, the math demands movement—of plants, of policy, and of our assumptions.

The original article was authored by Eva Schönwald and Lorise Moreau. The English version of the article, titled "EU jobs and US trade: Navigating change," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

ACEA / Cox Automotive / Kelley Blue Book. “April 2025 Kelley Blue Book Average Transaction Prices (tables).” Cox Automotive, May 2025.

BDI / Clean Energy Wire. “German industry urges next government to ensure lower energy prices.” Clean Energy Wire, Feb. 4, 2025.

DIHK. Economic Survey, February 2025 (Data). Berlin: Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce, 2025.

European Commission. “EU-US trade deal explained (Q&A).” Press Corner, July 28, 2025.

Eurostat. “Electricity price statistics—Statistics Explained.” Updated 2024–2025.

Guardian. “Another nail in the coffin: Germany’s car industry faces up to Trump’s tariffs.” The Guardian, Apr. 4–5, 2025.

IEA. Germany 2025: Energy Policy Review. Paris: International Energy Agency, 2025; and “Electricity 2025—Prices.” 2024–2025.

IRS / U.S. Treasury. “Credits for new clean vehicles purchased in 2023 or after”; “Final guidance for certain clean vehicle credits,” May 29, 2025; Federal Register final regulations on Sections 25E and 30D, May 6, 2024.

Reuters. “German car exports to U.S. slide in April, May as tariffs hit,” July 3, 2025; “Germany’s industrial output hits lowest since 2020,” Aug. 7, 2025; “Trump order lowering tariffs on EU autos still days away,” Aug. 6, 2025; “Kia to produce hybrids at Hyundai’s Georgia factory,” Mar. 28, 2025; “Toyota boosts investment in North Carolina battery plant,” Oct. 31,

U.S. Census / BEA. “U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services, June 2025,” and monthly FT900 tables. 2025.

USTR / White House. “U.S.–EU Deal Receives Widespread Praise,” July 29, 2025; “Fact Sheet: The United States and European Union Reach Massive Trade Deal,” July 28, 2025.

VDA (German Association of the Automotive Industry). “Employment in the automotive industry: Prognos study,” Oct. 28, 2024; energy-price competitiveness statements, 2022–2024.

VoxEU/CEPR. “EU jobs and US trade: Navigating change,” Aug. 2025.

Wallenius Wilhelmsen / Reuters. “Car shipper says US tariff haze still affecting auto trade flows,” Aug. 12, 2025.

ETUC. “US tariffs: EU must take emergency measures to protect jobs,” July 14, 2025; “EU urgently needs plan to protect jobs and production after US trade deal,” July 28, 2025.