Two Paths to the Same Shore: The Strategic Significance of Manila's Hard Lesson and Seoul's Narrow Ledge

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

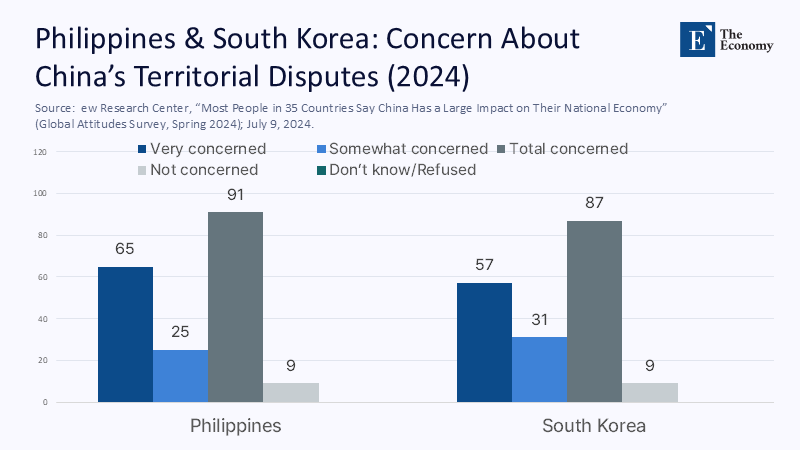

In 2024, 91% of Filipinos said they were concerned about China's territorial disputes—65% "very concerned." That single number captures a regional mood—and a policy inflection—better than any slogan about "great-power competition." It is not an abstraction: over the past two years, the China Coast Guard has repeatedly blasted Philippine vessels with water cannons and rammed them near Second Thomas Shoal and Scarborough Shoal, injuring sailors and damaging boats; just yesterday, Manila blamed China for yet another collision near Scarborough. In response, the Philippines accelerated access for US forces at nine Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) sites—several oriented toward the Taiwan Strait and the Spratlys—while hosting its largest-ever Balikatan exercises. South Korea reads this same barometer from a different vantage point: its security is anchored by ~28,500 US troops and newly formalized trilateral mechanisms with Washington and Tokyo, yet its economic arteries still run through China even as trade shares quietly tilt toward the United States. The lesson is not "choose a side," but match exposure to function: maritime denial for Manila; supply-chain de-risking for Seoul.

Shifting the Paradigm: From Binary Alignment to Function-Specific Alliance

The usual framing pits allies on a single continuum between Washington and Beijing. That image obscures what drives decisions in Manila and Seoul: threat geometry and economic exposure. The Philippines is a frontline archipelago facing gray-zone coercion at sea; its core requirement is credible maritime denial and resilient constabulary capacity. South Korea lives with the world's densest artillery threat from the North, depends on US extended deterrence, and trades at scale across a China-centric manufacturing ecosystem that still absorbs a large share of its intermediate goods. Reframed this way, alignment is function-specific: Manila deepens rotational US access and hardens coast guard and air-maritime domain awareness to stop salami-slicing. Seoul doubles down on trilateral deterrence and de-risks critical inputs—graphite, cathode precursors, legacy chip demand—without an abrupt divorce from Chinese markets. The timing matters: Chinese coercive tactics intensified in 2023–2025, while South Korean export data and US industrial rules pushed firms to rethink where strategic dependence sits. A policy that treats these as interchangeable "U.S.-versus-China" choices will misallocate scarce political capital.

The Philippine Proof: When Basing Politics Meets Gray-Zone Pressure

Philippine politics once evicted the US bases. In 1991, the Senate rejected a new treaty; by 1992, Subic and Clark were shutting down. Within three years, China erected structures at Mischief Reef inside the Philippine exclusive economic zone, and in 2012, it seized effective control of Scarborough Shoal after a standoff. Manila's answer over the past decade has been to rebuild alliance infrastructure without returning to permanent bases: the 2014 EDCA created rotational access and pre-positioning, and in 2023, four more EDCA locations were added—two in Cagayan and one in Isabela facing Taiwan, plus Balabac near the Spratlys. Water-cannon attacks in 2023–2024 that injured Philippine personnel underscored the urgency; 2024–2025 Balikatan iterations trained over 14,000–16,000 troops across the archipelago, improving joint targeting, logistics, and amphibious denial. The historical arc is stark: when Manila forced US forces out, coercion followed; when Manila reopened military access, deterrence capacity and allied investment returned. That is a functional—not ideological—lesson.

Seoul's Tightrope: A China-Facing Economy, a U.S.-Anchored Security

South Korea is "one step closer" to China economically and "one step farther" from US forward maritime friction than the Philippines, yet one treaty step more embedded with the United States in security terms. About 28,500 US troops deter North Korea on the peninsula, and the Camp David summit in August 2023 locked in regular trilateral consultations, information-sharing, and joint exercises with Japan.

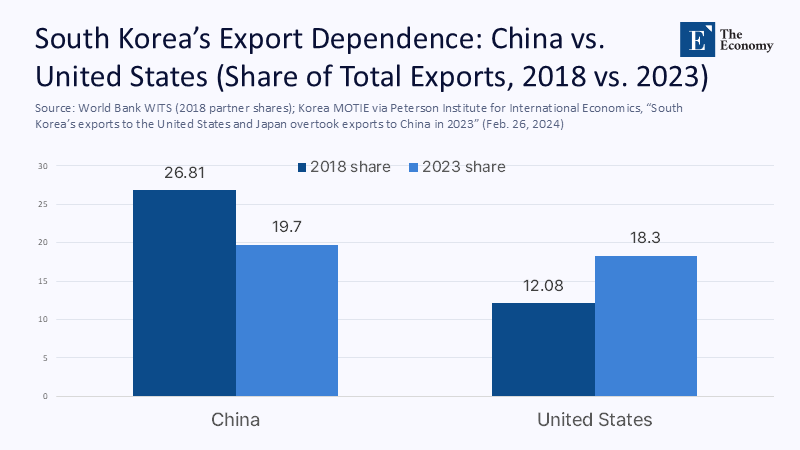

Economically, the picture is shifting. After two decades with China as the top buyer, late-2023 and early-2024 brought months when Korean exports to the United States overtook China, reflecting a structural rebalancing: South Korean shipments to China fell nearly 20% in 2023, with China's share dropping below 20% for the first time in twenty years. Official and research assessments point to Chinese import substitution reducing Korean intermediate-goods sales, even as AI memory demand props up overall exports. The policy implication is obvious: preserve deterrence and trilateral habits while methodically de-risking inputs and customers where Beijing's policy levers are strongest.

Force Posture Reality: Why Washington's Marginal Base Dollar Goes to Luzon

Why is Washington's recent marginal posture of investment concentrated in the Philippines rather than South Korea? Because marginal utility is maritime. EDCA sites in Cagayan and Isabela sit along the exits to the Bashi Channel, the same sea lanes a Taiwan contingency would contest. Balabac anchors the southwestern approach to the Spratlys. In July 2024, the United States pledged $500 million in security assistance for the Philippine military and coast guard; alliance statements repeatedly clarify that the Mutual Defense Treaty applies to attacks on Philippine armed forces, including coast guard vessels, anywhere in the South China Sea.

Meanwhile, Balikatan's evolution—the 2024 iteration involved over 16,000 personnel and expanded joint maritime strike and air defense training—fits a dispersal logic of rotational access rather than large fixed footprints. South Korea remains indispensable for peninsular deterrence and technology cooperation, but the forward edge against Chinese maritime coercion lies from Luzon to Palawan. Geography, not favoritism, explains the budget.

Trade De-Risking, Not Divorce: How China's Self-Reliance Shifts the Math

Both Manila and Seoul face diminishing returns from economic overexposure to China, though for different reasons. For the Philippines, the US is already the top export destination; Chinese demand matters more on the import side and for inputs into electronics assembly. For South Korea, the fulcrum is industrial policy. China's graphite export controls and the United States' evolving rules on "foreign entities of concern" expose Korean battery makers' dependence on Chinese anode materials and cathode precursors. At the same time, AI-driven chips pull Korean firms closer to US customers and fabs. Data across 2023–2025 show a structural slide in Korea's exports to China and rising shares to the United States, consistent with import substitution inside China. Seoul's answer is not decoupling but supply-chain hedging: multibillion-dollar initiatives to localize or friend-shore battery inputs, diversify semiconductor customers, and use trade rules to keep US tax credits in reach. Manila's answer is to monetize EDCA logistics, attract defense-adjacent infrastructure, and channel US and Japanese investment into dual-use maritime domains.

Anticipating the Counterarguments—and Why They Fall Short

One critique says the Philippines and South Korea are incommensurate: one faces daily maritime harassment; the other faces a nuclear-armed neighbor and global technology markets. That is the point. The comparison is not about identical threats but about how exposure dictates alignment. Another critique warns that a visible US posture in the Philippines invites escalation. Yet the record shows Chinese tactics escalated before EDCA's expansion and have continued regardless of restraint; clarifying mutual defense coverage for coast guard vessels reduces miscalculation by drawing a bright line. A third critique argues that China's market is too big to risk displeasing. Public opinion and trade data suggest otherwise: Filipinos are overwhelmingly concerned about China's disputes; in Korea, China's import substitution erodes demand for Korean intermediates while US demand and AI cycles rise. The last critique doubts the US's reliability. But institutionalized trilateral procedures after Camp David, allied exercises, and sustained funding signals provide continuity beyond electoral cycles. The prudent course is to treat deterrence and de-risking as parallel tracks that buy time for diplomacy.

From Cautionary Tale to Coordinated Strategy

The number that opened this column—91 % of Filipinos are concerned about China's territorial disputes—is a warning light for the entire region. It tells us that when gray-zone pressure grows, domestic politics harden, alliances revive, and basing math becomes maritime. The Philippines learned this the painful way after the 1991–1992 base closures and the subsequent losses of Mischief Reef and Scarborough Shoal; its remedy was a rotational architecture built for speed, dispersion, and joint denial. South Korea's lesson is different but parallel: de-risk critical inputs and customers while deepening trilateral habits that shoulder deterrence and crisis signaling. Policymakers should connect these tracks. Manila should leverage EDCA to accelerate coast-guard capacity, domain awareness, and civil resilience without turning the Philippines into a staging area for offensive operations. Seoul should turn short-term tariff reprieves and industrial subsidies into structural diversification—especially in battery anodes and legacy chips—without closing the door to pragmatic economic ties with China. If we follow the function, not the flag, both allies end up in the same place: less coercible, more interoperable, and more capable of shaping peace on their terms.

The original article was authored by Enrico V Gloria, an Assistant Professor of International Relations at the Department of Political Science in the University of the Philippines-Diliman. The English version, titled "50 years of Philippines–China relations offer lessons for engaging an indispensable power," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Al Jazeera. (2023, February 2). Philippines agrees to allow US wider access to military bases (notes $82m for EDCA sites).

AMRO. (2025, March). Annual Consultation Report—Korea 2024 (China demand, intermediate-goods shift).

AP News. (2025, August 12). Philippines blames China for ship collision in disputed South China Sea.

Biden White House (archives). (2023, August 18). Fact Sheet: The Trilateral Leaders' Summit at Camp David; Commitment to Consult.

BusinessKorea. (2024, May 22). South Korea logs first trade balance deficit with China in 31 years (export declines, shares).

CSIS—Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. (2024, January 30 & August 22). Tracking Tensions at Second Thomas Shoal; Shifting Tactics at Second Thomas Shoal.

CRS, US Library of Congress. (2023, September 12). US–South Korea Alliance: Issues for Congress (US troop levels).

Defense Department, United States. (2023, April 3). Philippines, US announce locations of four new EDCA sites; New EDCA sites named.

FPRI. (2023, May 24; 2023, June 14). America and the Philippines update defense guidelines; EDCA revived.

Global Times. (2025, March 22). US defense secretary's choice of Philippines instead of S. Korea … signals intention toward China.

IMF. (2025, February 5). Republic of Korea—2024 Article IV Consultation, Press Release.

KEIA. (2024, January 23). Korea exported more goods to the United States than China in December—trend?

Navy, U.S. Pacific Fleet. (2025, May 9). Philippines, US conclude Exercise Balikatan 25 (participant totals).

Pew Research Center. (2024, July 9). Global Views of China 2024 (Philippines 91% concerned; South Korea concern high; favorability trends).

Philippine Congress—CPBRD. (2025, March). 2024 Philippine Trade in Goods—Facts & Figures (US as top export market).

Reuters. (2023, April 3). Philippines reveals locations of 4 new strategic sites…; (2023, October 20). China tightens graphite exports; (2024, March 23). China coast guard uses water cannons…; (2024, July 30). US pledges $500m support for Philippine military and coast guard.

State Department, United States. (2025, January 20). US Security Cooperation with the Philippines; US Security Cooperation with Korea; (2024, August 31 & 2025, February 19). US support for the Philippines in the South China Sea (MDT coverage).

Taipei Times (via Bloomberg). (2024, January 2). South Korea's exports increase as shipments to US surpass China (monthly).

US Embassy Manila. (2024, April 17). Philippine–US troops to kick off Balikatan 2024 (16,000 participants).

U.S.INDOPACOM (Legal TACAID). (2024). Sierra Madre and Second Thomas Shoal: MDT implications (MDT applies to armed attacks on PH armed forces/public vessels).