London’s New Bridge to Growth: Why the UK–India FTA Turns Zero-Sum Fears into Economy-Wide Gains

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

Total UK–India trade hit £44.1 billion in the 12 months to March 2025—up 10.1% year-on-year—before a single tariff cut from the freshly signed deal has taken effect. The government’s impact assessment projects that once the agreement is implemented and staging is complete, bilateral trade will be nearly 39% higher than in a no-deal world, UK exports to India will be up almost 60%, and real wages will rise by about 0.19% across the country—roughly £2.2 billion a year in additional pay. These aren’t speculative blog claims; they are the United Kingdom’s benchmark figures, vetted through a computable general equilibrium model and sensitivity-tested. Meanwhile, Indian-owned firms in Britain have surged to roughly 1,200 companies, employing more than 120,000 people, with combined UK revenues in the tens of billions. In short, the flows are already deepening, and the agreement adds rails. That’s not a handout or a loophole; it’s comparative advantage made concrete, with India’s labour-intensive scale meeting Britain’s services and finance muscle in ways that lift overall productivity and pay.

Reframing the Debate: From Job-Protection Anxiety to Comparative Advantage in Practice

Opponents boil the agreement down to a single grievance: that the social-security “Double Contributions Convention” makes it cheaper to deploy Indian staff in the UK, undercutting locals. The critique resonates politically because the DCC exempts certain short-term transferees from paying into the UK National Insurance system for up to three years, with a mirror benefit for UK staff posted to India. But reducing a comprehensive FTA to this technical facilitation misreads both the economics and the law. The DCC is reciprocal, it prevents double payment, and it does not alter visa volumes, which remain governed by domestic policy. The agreement’s core is market access and tariff cuts: India reduces exceptionally high import duties; both sides bind in services access and digital trade; and non-tariff frictions are eased. In that general-equilibrium setting, the UK specializes more in high-value services, finance, autos, and beverages; India scales labour-intensive production and business services. That is the classic pattern of gains from trade, not a giveaway.

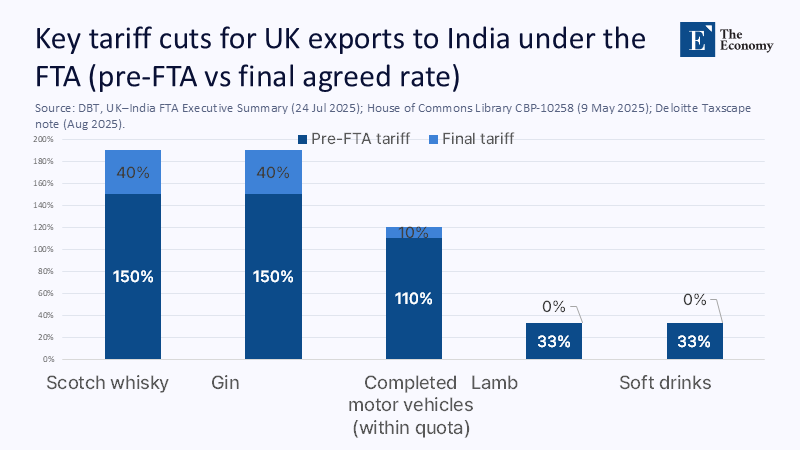

The government’s modelling quantifies those gains. It estimates a long-run increase of 0.13% in UK GDP (about £4.8 billion) and a 39% rise in bilateral trade, with import-duty savings for UK exporters of roughly £400 million at entry into force and around £900 million after 10 years of staging. Whisky tariffs fall from 150% to 75% immediately, then to 40% after staging; motor-vehicle tariffs drop to 10% within quotas. On the import side, the UK consumer benefits from cheaper textiles and apparel. At the same time, domestic output in those segments falls modestly—about 0.7% relative to no-deal—freeing resources for sectors with larger export gains. This is how modern FTAs deliver broad gains: by lowering input costs, expanding export headroom, and reallocating capital and labour toward higher-productivity activities.

Follow the Money: Capital Deepening and London’s Intermediation Edge

Despite the challenges of Brexit, London has demonstrated resilience, retaining its position as the world’s second financial centre and the dominant location for foreign-exchange trading. The latest Global Financial Centres Index places London just behind New York. BIS and ECB analysis confirm the UK’s unmatched FX role and continuing centrality in euro trading, even after some swaps activity migrated to the continent. This resilience is further underscored by the UK–India agreement, which arrives as Indian capital into Britain rises: UK inward FDI stock from India reached £12.4 billion at end-2023, up 22% on the year, and the number of Indian-owned businesses in Britain jumped to 1,197. A growing share of that footprint is in finance and professional services—the very channels through which London can intermediate India’s growth for global investors. The deal secures fairer treatment for UK services in India. It codifies digital-trade rules, making it cheaper and safer for British firms—especially mid-tier legal, accounting, and fintech outfits—to win mandates as India’s economy scales.

This is the replacement logic the public debate often misses. London cannot magically reclaim every line of business it lost with EU clients, but it can diversify its flow of mandates by servicing India’s expansion. The joint UK–India Economic and Financial Dialogue has already flagged corridors around GIFT City and London Stock Exchange access. As Indian companies raise equity and debt at home and abroad, the City will package, hedge, list, and advise—earning fees that are less sensitive to EU passporting and more tied to global growth. In other words, Indian capital is not a consolation prize; it is a new stream of high-margin work that complements Britain’s strengths and cushions the post-Brexit adjustment. This ability to adapt to new economic opportunities should reassure the audience about the UK's economic resilience.

Follow the Work: Cheaper Inputs, Higher Productivity, Bigger Export Headroom

Critics focus on import competition in visible consumer sectors, but the less visible channel is more powerful. UK firms buy a rising volume of Indian services as intermediate inputs—IT, design, back-office, analytics. When those inputs get cheaper and more predictable, British output per hour improves and export prices fall, which is exactly how small and mid-sized manufacturers expand in tough global niches. The impact assessment captures this compounding effect: UK exports to India are projected to rise nearly 60% in the long run, with the most significant gains in machinery and equipment, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, motor vehicles, and beverages. These sectors anchor regional clusters, from the West Midlands’ auto supply chain to Scotland’s spirits ecosystem, meaning the benefits spread beyond the M25.

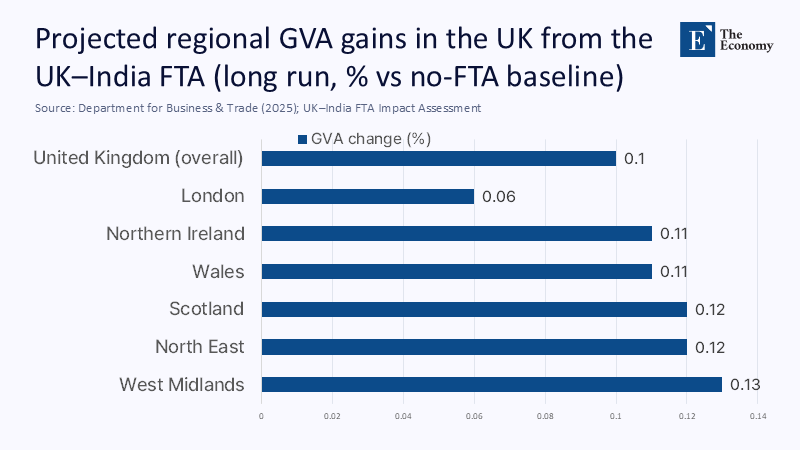

Geography matters for consent. The modelling shows every UK nation and English region gaining in gross value added, with the West Midlands and North East posting the most substantial relative increases, thanks to their concentration in machinery and motor-vehicle production. Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland also see measurable GVA uplifts. This distribution is not a by-product; it’s a consequence of where tariff cuts bite and where British capabilities run deepest. For university leaders and regional business groups, the implication is direct: co-design supplier development with Indian partners, channel students into applied placements linked to India-facing projects, and use the deal’s procurement and digital-trade provisions to de-risk first exports by local SMEs. This potential for growth in the UK's regions should inspire optimism about the country's economic prospects.

Mobility, Not a Flood: What the DCC Does—and Doesn’t

The DCC is a reciprocal social-security arrangement that prevents double payment when firms second staff across the corridor for up to three years. It allows a posted worker to keep paying into the home system—UK NIC for Britons in India; India’s EPF for Indians in the UK—and avoid duplicate contributions. It does not grant settlement, does not confer pension eligibility without meeting domestic thresholds, and does not change visa caps or points-based criteria. It lowers frictional costs for short-term deployment so joint projects can run without payroll riddles. Put plainly: it oils the gears of collaboration; it’s not an immigration amnesty.

If volumes are the worry, look at the numbers. Sponsored study dependants fell 85% in 2024 after policy changes; Skilled Worker applications between April 2024 and January 2025 were down around 10% year-on-year; broader visa issuance fell sharply across 2024. Indian nationals receive a large share of work visas, reflecting skill-match, but the pipeline is visibly tighter under domestic rules. The opposition’s argument—that the DCC opens the floodgates—conflicts with administrative reality. The policy lever managing volumes sits in the Home Office; the DCC sits in a separate drawer to avoid paying two social-security systems at once for the same short-term assignment.

Summarising the Opposition—and the Country-Level Rebuttal

Opposition leaders have framed the agreement as a package that, in their view, tilts toward overseas workers and squeezes vulnerable British sectors. They highlight the DCC’s three-year exemption, argue that it privileges foreign labour, and warn that tariff cuts will intensify competition in industries like apparel and leather. Some also question whether the City traded away leverage on visas to salvage a deal, contending that the pact “hollows out” domestic opportunity while savings on Scotch or cars are years away. These lines are crisp, emotive, and ready for a campaign leaflet. But their macroeconomics are partial.

Country-level evidence points the other way. The government’s assessment finds higher GDP, higher real wages, and higher GVA across all nations and English regions, with concentrated output losses limited primarily to textiles and apparel. Tariffs on UK export stalwarts fall in clear, staged steps; duty savings for British exporters start at around £400 million right away and rise to £900 million at complete staging. In parallel, London’s finance and professional-services ecosystem retains global scale and can intermediate Indian capital and mandates at growing volumes. That is the definition of a win-win at the national level: consumers get choice, regions with tradable strengths get orders, and the City gets work it can do better than almost anyone. The correct policy response is to cushion the concentrated losses, not to deny the aggregate gains.

Adjustment Without Austerity: Cushioning the Concentrated Pain

Open-economy realism admits that a small set of firms will feel the squeeze. The UK textiles, apparel, and leather complex faces a projected 0.7% output decline versus the no-deal baseline as cheaper Indian imports arrive. The worst answer is nostalgia; the best answer is targeted transition. Time-limited wage-top-ups tied to reskilling, portable training vouchers redeemable at local FE colleges and approved private providers, and co-funded capital grants for moving into technical apparel, medical textiles, or aerospace fabrics offer a concrete bridge. Procurement can help too: link UK tenders for NHS kit or defence textiles to supplier development plans with Indian counterparts, so exposure produces capability rather than closure. None of this requires a new theory; it requires administrative clarity and honest communication.

Funding the cushion is straightforward. Even under conservative assumptions, the real-wage and GDP lift dwarfs any transitional support outlays. A small carve-out of the productivity dividend—plus the expected exchequer benefit from higher taxable profits in expanding sectors—can underwrite the package. The environmental arithmetic warrants candour: the deal is estimated to raise UK greenhouse-gas emissions by around 0.8 MtCO₂e (0.21% of 2019 levels) as industry expands. That figure sits against an overall downward trend. It can be offset with targeted decarbonisation support for energy-intensive segments, financed in part by the same productivity gains the FTA unleashes. Adjustment is not a footnote to trade policy; it is what keeps an open economy open.

Measuring What Matters: Methods, Uncertainty, and Why the Direction Is Robust

No impact assessment is a crystal ball. But we should pay attention when independent indicators point in the same direction. The factsheet shows trade rising before implementation, suggesting pent-up demand. The GFCI keeps London in second place globally, signalling that the City retains its institutional network effects. BIS and ECB data confirm London’s pre-eminence in FX even as some euro swaps decamped; that is the plumbing through which services, mandates, and capital flows move. Layer on the Grant Thornton/Confederation of Indian Industry tracker documenting a record year for Indian-owned businesses in the UK—including rising revenues and headcount—and the inference becomes stronger: the corridor is already thickening on market fundamentals the FTA formalises.

Transparency about uncertainty helps, too. Implementation is not instantaneous; many tariff cuts are staged over a decade, and the agreement still awaits domestic procedures before entering into force. Global demand cycles will modulate outcomes, as will India’s pace of domestic reform. Yet the model’s sensitivity analysis shows a tight band for GDP gains in 90% of simulations. Meanwhile, auxiliary policies—the DCC to smooth postings, digital-trade provisions to cut transaction costs, SME contact points to shepherd first-time exporters—reduce the non-tariff frictions that derail smaller firms. In other words, even if the precise numbers move, the sign is sticky: cheaper inputs, wider market access, and a stronger finance corridor make the UK a more competitive platform for selling to a fast-growing, scale economy.

A Durable Win–Win, If We Choose to Use It

The UK–India agreement is not a magic wand, and it will not spare every firm from competition. It does something more valuable: it aligns Britain’s strengths with the world’s fastest-growing large market, and it gives businesses the rules, channels, and certainty to act. India’s labour-rich services and manufacturing meet the UK’s depth in finance and high-value services; tariffs fall in the places Britain can sell most; and a reciprocal DCC removes a costly deterrent to collaboration without opening the migration floodgates. The headline gains—higher wages, higher output, and broader regional benefits—are not a politician’s flourish but the government’s own central estimates. The choice, then, is not between “protecting jobs” and “helping India”; it is between managing a concentrated transition or forfeiting economy-wide gains. Suppose ministers fund the cushion, universities and firms build capability with Indian partners, and the City leans into intermediation. In that case, the trade statistic that opened this column will look like a starting point rather than a peak. That is what a real win-win looks like in an era of brittle globalisation: practical, measured, and relentlessly focused on making the most of complementary strengths.

The original article was authored by Durgesh Rai is Associate Professor at the Rashtram School of Public Leadership, Rishihood University, Delhi NCR, Sonipat, Haryana, India. The English version, titled "UK opposition parties up in arms about trade deal with India," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Associated Press. (2025, July 24). Leaders Starmer and Modi hail long-sought India-UK trade deal as historic. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Bank for International Settlements. (2022). Triennial Central Bank Survey: OTC foreign exchange turnover in April 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Bank of England. (2022). Summary of UK BIS Triennial Survey results 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Department for Business & Trade (UK). (2025a, July 24). Impact assessment of the Free Trade Agreement between the UK and India (executive summary). Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Department for Business & Trade (UK). (2025b, May 6). UK-India trade deal: conclusion summary. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Department for Business & Trade (UK). (2025c, July 23). UK-India Double Contributions Convention (DCC) — explainer. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Department for Business & Trade (UK). (2025d, August 1). India—UK Trade and Investment Factsheet. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

East Asia Forum. (2025, August 12). UK opposition parties up in arms about trade deal with India. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

European Central Bank. (2023, June). Impact of Brexit on the international role of the euro (Box: London’s euro-FX share). Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Grant Thornton UK LLP & Confederation of Indian Industry. (2025, June 18). India Meets Britain Tracker 2025. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Home Office (UK). (2025, February 27). Immigration system statistics, year ending December 2024: Summary of latest statistics. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Home Office (UK). (2025, March 13). Monthly monitoring of entry-clearance visa applications (to January 2025). Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Long Finance / Z/Yen Partners. (2025, March 20). Global Financial Centres Index 37. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Migration Observatory (University of Oxford). (2025, February 27). Migration statistics show dramatic fall in visas granted in 2024. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Reuters. (2025, June 9). Fact check: UK–India deal’s social-security tax break applies to posted workers, not all Indian workers. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Comment