Money Without Soldiers: The Belt and Road' Base Camps' in the Pacific and the Sri Lankan Test

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

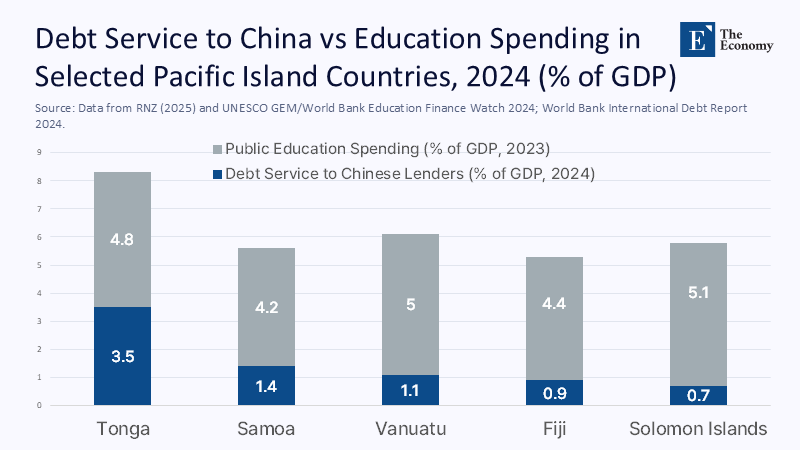

In 2023, developing countries spent a record $1.4 trillion on servicing external debt, while interest alone soared to $406 billion, a 20-year high that squeezed health, climate preparedness, and, most critical to long-term sovereignty, education. In 2025, the repayment tide rises further: developing countries will transfer about $35 billion to Chinese sovereign lenders, with the poorest seventy-five countries owing about US$22 billion – a net outflow that can easily exceed the small states' budget for teachers, appliances, or school transportation. For Pacific island countries (PICs), where cyclones and distance make education costly and fragile, this cash leak is not an abstract concept: It determines which classrooms will be repaired after the next storm, which rural teachers will be retained, and how quickly schools are connected to undersea cables. Money, in short, is the quiet instrument of power. Western creditors used it throughout the post-colonial era. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is now doing the same – seeking out "base camps" in the Pacific through budgets rather than barracks. The question is not whether money buys influence, but whether it buys growth that Pacific voters can feel.

From the colonial books to the Belt and Road balance sheets

The proper framework for Pacific dominance is not map lines or port calls, but budget lines. Western and multilateral lenders have long forged policy space in the former colonies through conditional loans and aid funds. China's BRI uses a similar toolbox, often with fewer political commitments but heavier confidentiality. For classroom results, the decisive constraint is fiscal space. UNESCO and the World Bank show that the share of global aid going to education fell from 9.3% (2019) to 7.6% (2022), only partially recovering in 2023. At the same time, PICs face annual expected disaster losses of around 2-3% of GDP, a structural tax on public services that turns routine debt servicing into a problem of sovereignty when storms escalate. The allusion is simple: Infrastructure financing – Chinese, Western, or multilateral – should be judged by whether it expands the fiscal space for learning over twenty years, not just by ribbon-cutting. This is the axis from geopolitical theater to actually being in the classrooms.

Sri Lanka, debt, and the trap that was not

The ghost haunting the debates in the Pacific is Sri Lanka. Many commentators claim that the BRI's borrowing 'destroyed' its economy. The data point elsewhere. Until the time of the default, international government bonds were the most significant external obligation. At the same time, Chinese sovereign and trade claims accounted for about one-fifth of the public external debt at the end of 2021. Sri Lanka's crisis reflected a cocktail of tax cuts, weak stocks, and the pandemic's blow to tourism, combined with global interest rate hikes. This mix matters to Pacific because it warns against one-sided stories that obscure the real risks: opaque contracts, short maturities, and weak revenues from any creditor. If Pacific leaders internalize the right lesson, they will publish complete debt registers, realistically compare project cash flows, and fix revenue systems before scaling costly projects. This is how to resist leverage, whether the lender is sitting in Beijing, Canberra, Washington, or the bond market.

Hambantota's narrative — often referred to as debt forfeiture for assets — is also shrinking under control. An investigation by Sri Lankan analysts and the China Africa Research Initiative found no default in 2017 on port loans. Instead, the government leased the facility commercially to raise foreign currency while continuing to service initial debts. Hambantota was arguably a bad investment, and A political lever, but it was not a legal seizure. For PICs, the operational conclusion is clearer contracts, not fatalism: keep commercial management arrangements separate from state guarantees, and never allow security clauses to affect financial concessions. The road to dominance is the term sheet, not the tweet.

Base Camps Without Bases: Security Pacts, Cables, and Scholarships

If the Japanese empire of the 1930s built the Pacific range with guards, the China of the 2020s seeks "base camps" without bases: police cooperation, digital infrastructure, and programs among people. The Solomon Islands signed a security agreement with Beijing in 2022 and a policing pact in 2023. Australia, for its part, responded with the support of regional police and the help of big-ticket companies. Meanwhile, subsea cable options have become strategic: Australia funded Coral Sea Cable and subsequent expansions to keep Huawei out, framing connectivity both as an economic necessity and as a security perimeter. For education, the telegram is not a metaphor – it is the difference between a science teacher broadcasting live on islands and a school permanently offline. The influence, in this area, reaches as far as bandwidth, device procurement standards, and curriculum platforms.

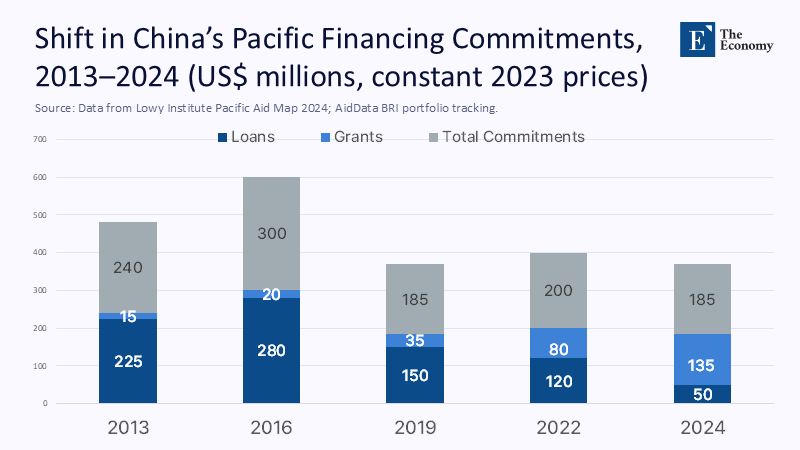

China has also readjusted its funding in the Pacific. After a pause, activity has recovered with a tilt towards grants and "small and beautiful" projects. The prime example is the US$135 million (2024) upgrade of Fiji's Vanua Levu Road – China's most significant project ever funded by grants in the Pacific. Solomon Islands and Vanuatu in 2022-2023. Grant axes matter because they reduce short-term debt risks while still creating goodwill and trade footprints. They also set a benchmark: if Beijing can offer grant packages in cyclone zones, other partners will have to match this favorability so that infrastructure competition becomes a race for supply quality of service and not repayment leverage.

Will it work? A budget test for growth

The growth test is a numerical test that is unforgiving. Tonga's external debt is close to 38% of GDP, with more than half due to China; repayments rose to around 3.5% of GDP in 2024 and will remain high until 2027. Compare this single line item to the SDG benchmark that countries spend 4-6% of GDP on education. A cyclone season that forces an extra percentage point of GDP to service debt or emergency borrowing can wipe out one-fifth of the classroom's budget. The numbers vary by country, but the compromise is consistent in remote atolls: pay the note or pay the teachers. The BRI will only "work" if major projects protect - and ideally expand - the fiscal space of human capital precisely in these years. Otherwise, ports and roads are turned into monuments surrounded by schools with insufficient resources.

The macro backdrop is mixed. The World Bank's Pacific Economic Update shows that regional growth is slowing from 5.8% (2023) to ~3.6% (2024) as the recovery weakens, while disaster risk and tight revenue bases keep debt vulnerabilities elevated. Investment growth is projected to be lukewarm this decade, even when connectivity and climate resilience require enormous Upfront costs. In this context, the current global profile of the BRI—as a net drain for many developing countries because repayments now exceed new disbursements—exacerbates the stakes: without concessions, transparency, and quick relief after shock, lender leverage increases precisely when classrooms need more capital. The Sri Lankan comparison returns: Not a morality game, but a warning about the sequence and stress of cash flow.

Course Correction: Planning Finance That Builds Dominance

First, contract transparency must be non-negotiable across all packages – BRI, G7, or multilateral. Confidentiality clauses and unclear distinctions between policy banks and 'commercial' sovereign lenders have delayed restructurings under the G20 Common Framework; PICs can reduce this risk by publishing debt registers, linking disbursements to open public procurement, and ensuring independent cost-effectiveness checks. The goal is not to shame any creditors, but to prevent the capture of the elite and to enable rapid, comparable relief for all categories of creditors when disasters strike. Transparency is not against China; They are in favor of sovereignty.

Second, the first condition for education should determine the financing of Pacific infrastructure. Each flagship port, road, or cable should incorporate legally binding provisions that delimit teachers' payrolls during repayment; expand school connectivity to the last-mile islands, and fund the training of teachers on platforms that allow cables. UNESCO's technology in the Pacific in education emphasizes the enormous logistical costs of learning in all oceanic states. If infrastructure dollars ignore these costs, growth underperforms and dependence deepens – whoever the financier is. To put it bluntly: a cable that doesn't cable schools is geopolitical theater, not growth.

Anticipating the reviews – and the evidence

Criticism first: "BRI debt is destroying economies." Sri Lanka shows a more complex picture, with ISB and fiscal policy at the center of the crash. Chinese borrowing added pressure, and opaque deals magnified the risk, but the system failed at many nodes. This nuance matters because misdiagnosis leads to poor planning. The solution is universal standards – open contracts, realistic revenue projections, and disaster-induced stagnation – so that any creditor's leverage is limited by rules that voters can see.

Criticism two: "The West has long used money as a control. Why should we single out China?"If Australia funds a police academy, while China trains officers under a separate pact, the safety valve is not the color of the flag. It is whether both agreements leave intact the budget for training in cyclone years and provide tangible learning tools – bandwidth, devices, trained teachers - in remote schools. Safety pacts and cables become stabilizing, not extractable, when the classroom is baked into the design.

Criticism third: "First, the hard infrastructure. Classrooms can wait." In small, dispersed economies, this sequence fails. Ports and roads only boost growth when local workers can use them productively. That means literate graduates, professional pipelines, and digital fluency. The geography of the Pacific multiplies the cost of school education. Underinvestment in people turns shiny assets into untapped assets. – which both Beijing and Western partners can possess – is to link each specific flow to measurable human capital gains over a ten-year horizon.

Basic Camps of the Mind

The data points to a sober verdict. Debt servicing is at historically high levels worldwide. Payments to Chinese lenders peak in 2025, even as donors' attention to education has receded. In the Pacific, where storms take two to three points away from GDP and distance taxes on every textbook and education, Money will continue to project power as surely as ships ever did. This is not new; It is how Western creditors shaped post-colonial choices for decades. What's new is the opportunity to rewrite the terms. If China wants the BRI to hold up in the Pacific — instead of being remembered as a 2010s borrowing craze turned into a 2020s collection move — it must lead to hurricane zone subsidies, transparent contracts, comparable relief, and education for staff and cable at every school on the island. If Western partners want to be credible alternatives, they must do the same. The "grassroots camps" that will win the century are classrooms with power and bandwidth, taught by well-paid local teachers. Sovereignty is ultimately trained, or it is not.

The original article was authored by Charles Hawksley, an Associate Professor in the School of Humanities and Social Inquiry at the University of Wollongong. The English version, titled "Pacific sovereignty maintains the same malleability down China’s belt and road," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

AidData / Lowy Institute. (2025, May). Maximum repayment: China's global borrowing. Lowy Institute interactive and PDF.

China Research Initiative for Africa (SAIS-CARI). (2022). Evolution of Chinese lending in Sri Lanka since the mid-2000s (Moramudali & Panduwawala).

Reuters. (2019, August 27). Australia completes laying of subsea cable for Pacific allies, blocking Huawei.

Reuters. (2021, June 24). Pacific island is turning to Australia for undersea cable after being rejected by China.

Reuters. (2024, July 3). Sri Lanka reaches a provisional agreement to revise $12.5 billion of bonds.

RNZ. (2025, April 25). China defends Tonga's loans amid growing debt concerns (includes 2024 DSA data).

Government of the Solomon Islands. (2023, July 19). Under the SI-PRC Police Cooperation Agreement.

UNESCO GEM Report. (2024). Pacific Report - Technology in Education: A Tool in What Terms?

UNESCO GEM / World Bank / UIS. (2024). Education Finance Watch 2024 (and related factsheets): the share of education aid decreased to 7.6% in 2022.

World Bank. (2023, December 6). Building a resilient future in the Pacific (annual disaster losses ~2-3% of GDP).

World Bank. (2024, October 15). Pacific Economic Update—Summary (growth ~3.6% in 2024).

World Bank. (2024, December 3). International Debt Report 2024—Press release (US$1.4T debt service; US$406 billion).

Lowy Institute. (2024, Nov.). Pacific Aid Map—2024 Key Findings (US$135 million grant from China to Fiji, grant axis).

Comment