Taxpayers First, Research Opens: Japan's Scholarship Reworking Is the Right Solution for PhD Funding

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

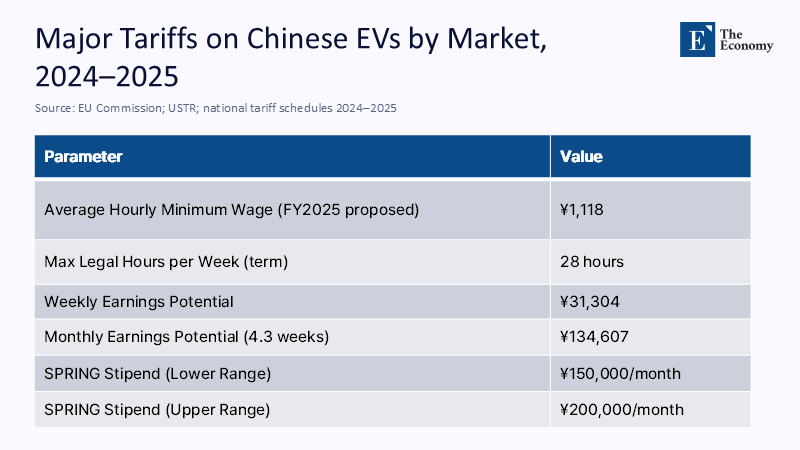

¥1,118. This is the national average hourly minimum wage proposed by Japan's labor committee for the 2025 fiscal year. Under student visa rules that allow for up to 28 hours of paid work per week during tenure and more hours on vacation, a doctoral student can legally earn about ¥135,000 a month before taxes. This amount is now close to the monthly living support threshold that is paid under Japan's SPRING PhD program at many universities (usually ¥150,000, with some programs higher). At the same time, international enrollment has returned to record levels, with 336,708 international students in 2024 and 58,215 in graduate schools. The largest single nationality is Chinese, accounting for 36.7% of all international students. In this environment, a broad, ethnicity-blind cash allowance for the cost of living copies wage policy and softens public support. Reorienting taxpayers' living support towards citizens, while keeping research money open to all, is a fair and balanced approach. It is fiscal discipline aligned with incentives.

Redefining the argument: living allowances are social security, not a universal right

The central question is not whether international doctoral students – including many from China – contribute to Japan's research ecosystem; some do, remarkably. The policy question is narrower: what problem was the SPRING grant designed to solve, and what is the most effective, publicly defended tool to solve it now? Targeted a specific domestic friction – the reluctance of Japanese students to enter doctoral programs due to the cost of living risk. In mid-2025, a group of experts supported a revision that would exclude foreign postgraduate students from the cost of living component as early as the 2027 financial year, while leaving support for research. This is a refocusing of the purpose, not a renunciation of internationalization. It treats living allowances as social security for citizens and research grants as strategic investments – open to any researcher who can justify the lab.

This reform matters because legitimacy leads to resilience. Public trust is eroded when a program promoted as a fix for a domestic pipeline ends up funding significant living costs for foreigners during a cost-of-living squeeze. The revision keeps labs free to hire international candidates with research money, including the continued eligibility of foreigners for research expenses – reported at around ¥400,000 – ¥1.1 million – while keeping cash "rent and rice" for taxpayers' children. This separation clarifies the roles: the government mitigates domestic risk; principal investigators fund their teams based on projects; International students continue to enter funded roles where they are proven to increase results. This long-term perspective instills optimism in the future of doctoral funding in Japan.

Incentives, not intentions: The salary-visa arithmetic that politics must face

Politics must be aligned with behavior, not supposed motivations. Two parameters shape the behavior of all students, domestic and foreign. First, Japan's 28-hour rule gives doctoral students legal access to paid work. During vacations, they can work a full eight hours a day. Second, the national minimum wage is rising rapidly, with proposals for the financial year 2025 around ¥1,118 per hour. Multiply these numbers, and the legal monthly earning potential for a student approaches the lowest step of SPRING's living expense assistance. In large metro areas, available part-time work makes life without benefits reasonable for many. If wage policy and visa rules already bridge much of the cost-of-living gap, the marginal value of a broad cash allowance shrinks – and the political cost rises. Scholarship has been swept away in acting as a generic complement, rather than as the decisive catalyst for which it was built. This underscores the need for policy to align with student behavior and motivations, ensuring its practicality and effectiveness.

There is a second incentive: cross-border wage arbitration. In 2025, Beijing's official hourly minimum wage is about 27-28 RMB, and Shanghai's is about 25 RMB. In the prevailing exchange rates, this equates to about half of Japan's proposed average minimum wage. A Chinese doctoral student weighing options sees a legitimate profit stream in Japan that can be multiples of casual earnings at home, even before holiday allowances. It is not a question of questioning the motives; It is to admit that rules and wage thresholds matter. If politics makes sense to come for income security first and research second, some newcomers will do just that. In this case, citizen-only living allowances combined with open research funding force the system to reward research contributions rather than additional visa income.

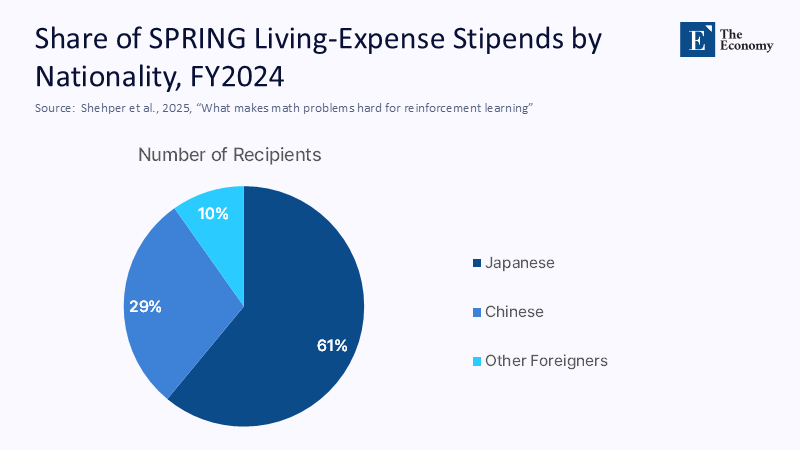

Concentration and Capacity: Why a Heavy Hiring from China Sharpens Trade-Offs

China accounted for 36.7% of all international students in Japan in 2024. Overall, international numbers are at record levels, and graduate-level enrollment is steadily increasing. In such circumstances, the impact of a blind nationality living allowance falls largely on a single foreign group. This is a recipe for political reaction, particularly when the allowance doubles the earning capacity available through legal work. Adapting the grant rule, while keeping access to research open, limits over-reliance on a pipeline without closing the door to real talent. It also pushes departments that have relied on inflows of foreign fees and allowances to the correct size or fund doctoral chairs through grants rather than general aid.

Critics warn that this will "end graduate school," where international students are in the majority. Comparisons with the UK and the United States are often misplaced. In the UK, most full-time postgraduate students are not British; in the US, 34-35% of all doctorates, and the majority in some STEM fields, go to temporary visa holders. So, a broad wage cut holds many programs. Japan's goal is different: to rebuild a domestic doctoral pipeline while maintaining a competitive, project-funded welcome for global talent. The revision meets this objective. Where labs can offer funded roles in grants, they will hire strong international candidates – including Chinese PhDs – based on advantages. Where the programs cannot, the capacity should be shrunk. This is not insular; It is quality control. This emphasis on maintaining a competitive, project-funded environment for global talent underscores the policy's commitment to excellence and its long-term goals.

Results, not staff: The case of excellence for the redirection of the yen

Japan's bibliometric trendlines are clear. In a fractional count of the top 10% of cited papers, Japan ranks roughly 13th globally, despite previous pressures for internationalization. If the goal is academic excellence – measurable influence, faster publication time, stronger ties with industry – then spending the marginal yen on RA/TA lines, equipment, and stable, multiannual project grants will generally exceed the same yen spent on broad living grants. The revised plan moves in this direction: a reserve of live cash for citizens to correct a specific inadequacy of the domestic market. Fund research roles competitively, open to any nationality, and keep laboratories to produce measurements. Public money should buy research time and proven results, not reproduce the profits of a rising minimum wage.

The excellence argument also responds to a long-standing concern that excluding international students from living allowances will push back "the best and smartest." The most mobile, high-potential candidates—from China or anywhere else—meet the research conditions: mentoring, equipment, co-writing networks, and predictable funding horizons. An RA line in a world-class project outweighs a general grant almost every time. The Role of the State is to fund these projects and demand accountability. The role of laboratories is to recruit worldwide to fill them. The role of the allowance is to reduce the risk of doctoral studies for citizens so that Japan's pipeline does not collapse below opportunity costs. This division of labor is how a system that prioritizes taxpayers and opens up talent produces more top work.

Application Working: Guardrails, Compliance, and Laboratory-Level Financing

The details of the planning will determine success. First, keep foreigners eligible for research money and make this flow predictable: the exposure of universities ranges from around ¥400,000 per year for research expenditure to over ¥1 million in some programmes. Link these flows to project milestones so that the money funds outflows, not residences. Second, apply the 28-hour rule. Universities should create compliance tables that require monthly self-certification linked to payroll records, where possible. Continued violations should carry visa risks for students and budget penalties for laboratories. Third, require principal investigators to present a funding plan for each PhD student hired – citizen or foreigner – that covers the cost of living through RA/TA work, industry co-funding, or department budgets, rather than defaulting on central grants.

Transparency will maintain legitimacy. Publish annual dashboards, by university and sector, reporting PhD wear rates, time to degree, placement outcomes, funding mixes, and the share of PhD students by nationality and type of funding. Combine the review of grants with the expansion of multi-annual, peer-reviewed project grants in priority sectors – semiconductors, Green manufacturing, and advanced materials – so that laboratories have fundamental tools for funding roles. Finally, make it clear to current and future students: living allowances are social security for citizens; research funding is open to all and project-based; Legal work remains available under visa rules, but it should not sideline research. The message is not "Japan First" in science. Is "Results First", with a fiscally honest social safety net for taxpayers.

Predicting repulsion: fairness, reputational risk, and talent flow

Concerns about fairness come in two forms. One says the rule is discriminatory. However, the policy only reserves cash for the cost of living for citizens, leaving research funding open. This is a classic distinction between social policy and investment. Another says it will tarnish Japan's scientific brand. This danger exists if the state cuts living aid and starves programs. Discussion Review does the opposite: it protects the eligibility of research costs for international students and pushes laboratories to fund doctoral roles through fellowships, not general fellowships. Japan can and should continue to hire international PhDs, including those from China, in funded, deliverable research groups. This is the brand we need to cultivate.

A second backlash claims that the policy ignores how some fields rely heavily on international students for basic functioning. This criticism is most true in the UK and parts of the US, where a substantial share of graduate enrollment is non-domestic and where scholarships and tuition fees from abroad guarantee departmental budgets. Japan's structure is different, and the goal of the policy is clear: reducing domestic bottlenecks while competing for global talent through project funding. Suppose some programs in Japan survive only because international students can supplement their national allowance with visa-based work income. In that case, that's a sign of re-instrumentalization or abolition — not a reason to maintain a non-aligned subsidy.

Public sentiment is genuine and must be addressed with data.

Forums and comment threads are not politics, but they are windbreakers. Reactions to the change in allowances show two fixed patterns: many citizens read the program as taxpayers who bear the cost of living for foreigners. Many international students read the change as a sign of exclusion. The way is to keep the bright line clear. Living allowances serve a domestic social purpose. RA/TA lines and competitive scholarships remain open to all based on contribution. If the ministry announces this – with figures on how many foreign doctoral students receive research support and how many are hired in funded projects – the sentiment will evolve in tandem with the results.

And here's the quiet, realistic truth that many Japanese labs already know: professors who want a particular foreign candidate can and do put together packages of research budgets, corporate partnerships, and targeted scholarships. The revision doesn't close that path; it normalizes it; it curbs loosely managed competency-filling programs, while protecting competing teams that can place graduates and publish. It's the difference between a recruitment strategy and a research strategy – and only the latter moves the referral needle.

From benefits to strategy: A taxpayer-first arrangement, open to talent

Japan isn't closing its doors to international doctoral talents; it's closing a loophole that has turned a domestic social security tool into a generic complement for anyone holding the correct visa. The numbers make the case. With a proposed average minimum wage of around ¥1,118 per hour and a maximum working limit of 28 hours, students' statutory earnings are now approaching the lowest step of SPRING's monthly support. International student numbers are on record, and the largest single group is Chinese. In this context, the maintenance of living allowances for citizens does not constitute xenophobia; It is fiscal alignment. Keeping research money open to all nationalities ensures that powerful labs can still hire the best – and be held accountable for the results that take Japan out of its middle benchmark plateau. The deal to be offered is simple and strong: citizens receive cost-of-living insurance for the reconstruction of the domestic doctoral pipeline. Global Talent competes for funded roles in projects that perform. This is the only balance that taxpayers will support and the only one that can move the boundaries of research.

The original article was authored by Stefan Aichholzer, a PhD student at the Graduate School of Human Sciences, Osaka University. The English version, titled "Japan’s scholarship rework reveals uneasy relationship with Chinese students," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Asahi Shimbun. (2025, August 1). The cut in funding for international students wins the nod from the ministry's committee.

Asahi Shimbun. (2025, June 27). The government will reduce the allowances for the living expenses of foreign doctoral students.

. (2025, July 16). Shanghai is raising the minimum wage in 2025. hourly minimum of RMB 25.

China Briefing. (2025, August 8). Minimum wages in China (Beijing hourly RMB 27.7; Shanghai monthly RMB 2,740).

HESA. (2025, March 20). Higher Education Student Statistics 2023/24: Location and postgraduate composition.

JASSO. (2025, April 1). International Student Survey in Japan, 2024 (PDF).

JASSO / Study in Japan. (N.D.). Part-time: 28-hour rule and holiday limits.

Kyodo News. (2025, June 26). Japan is seeking to end assistance for living expenses to foreign doctoral students (research support remains up to ~¥1.1 million).

Kyodo News. (2025, July 12). FOCUS: Cut in foreign doctoral student support agreements hit Japanese academia (living assistance up to ~¥2.4m).

NISTEP/JST. (2023, Aug.–Sep.). Japan drops to ~13th place for the top-10% of cited documents.

Nippon.com. (2025, June 9). Foreign students in Japan set a new record in 2024. China 36.7%.

NSF/NCSES. (2025, May 7). Nearly half of the 2023 US PhDs on a temporary visa were from China or India (share data by field).

Reuters. (2025, August 4). Japan's commission proposes a 6% increase in the minimum wage, on average to ~¥1,118.

Shimane University S-SPRING. (2024, November 13). Livelihood support ¥150,000/month, research funds ¥400,000–700,000.

Tohoku University IGPAS. (2024, September 6). Grant of ¥180,000/month, annual research grant of ¥340,000.

University of Tokyo. (N.D.). Part-time positions: 28-hour summary of rules.

Comment