The womb and the wallet: Why education no longer neutralizes the birth advantage in Japan - and what the Netherlands is now proving

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

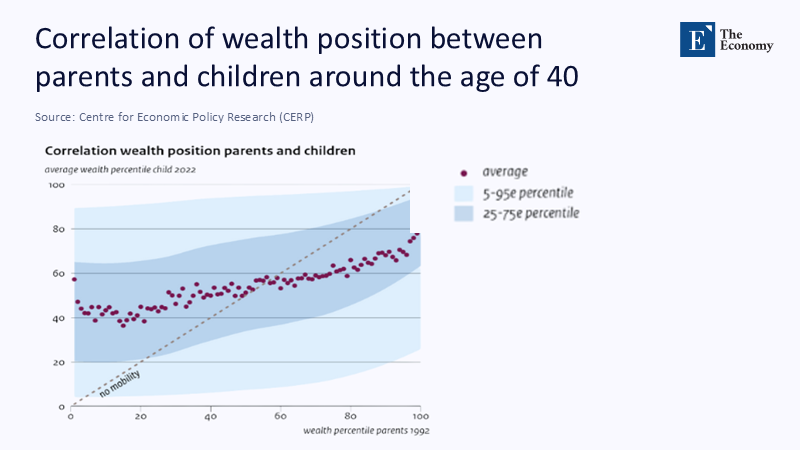

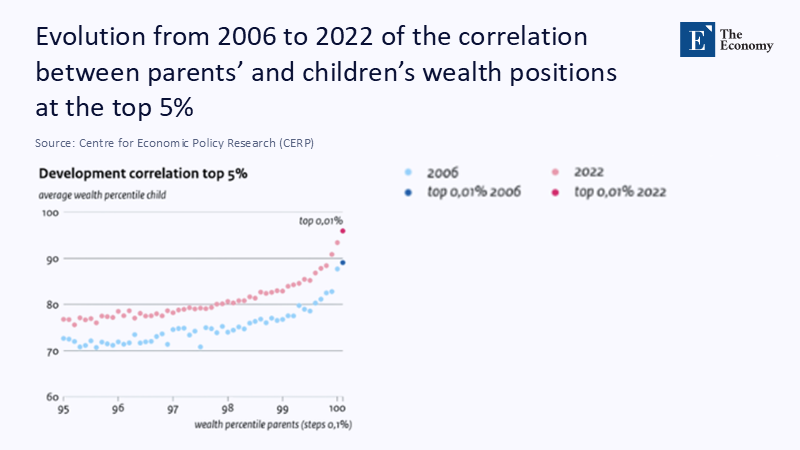

In the Netherlands today, the birth of children to parents in the top 0.01% of the distribution of wealth is linked to the landing, since the early 1940s, in the 96th percentile of wealth, before most legacies arrive. The children of the top 1% have an average of the 82nd percentile. The associations between brothers suggest that approximately one-third of the fluctuation of adult wealth is explained by the family and the familiar environment, and the parent-child wealth bond has been reinforced since 2006, especially at the top. Combine this with the national image of distribution: from the beginning of 2023, the wealthiest 10% of households own 56% of the total net wealth. Stack these numbers next to a cultural line that has gained ground in Japan — "which university a baby will attend can be predicted in the womb" — and the claim that grades neutralize provenance starts to look graphic. The data shows a more straightforward, colder truth: the Richness of the womb. He is increasingly writing the first draft of adult outcomes.

Redefining the Problem: Shifting from the 'Degree as an Equalizer' to the Reality of the OED

Much of the policy still assumes that higher education weakens the effects of family background—that university credentials "flatten" life. Recent Japanese evidence refutes this hypothesis. A 2024 study using nationally representative mobility surveys finds that college does not act as a great balancer in Japan: professional returns to a certain extent are not larger for students from less favoured backgrounds. The Netherlands presents a parallel pattern of wealth: the parents' position provides for the position of adults. Even before the bequests and the correlation have intensified at the top. PISA 2022 adds context: socio-economic situation explains 12% variation in mathematics performance in Japan and 15% in the Netherlands. The Dutch performance gap between SES students in the upper and lower quadrant is 106 units in mathematics - well above the OECD average. The redefinition is as follows: the results are better understood through the triangle OED - Origin - Education - Destination - not only through education. Grades still matter. Merely mediate, instead of deleting the source.

The OED Model in Japan: Understanding how Origin Is Channeled Through School Education to the Destination

In Japan, OED channels run through selective high school tracks, entrance exams, and a huge Shadow Education Ecosystem (JUKU) which enhances the ability of privileged families to transform descent into educational credentials. The commission's post-pandemic data show that SES-based inequalities in terms of study time, ICT use, and 'active learning' practices have widened somewhat, but more importantly, these gaps pre-COVID-19 and are still present in all cohorts. The PISA 2022 profile places Japan among the high-performance systems, relatively fairly; however, parity here means that SES continues to predict performance, slightly lower than the OECD average. To put it another way: Japanese compulsory education softens - but does not break - the O→E→D pipeline. And when the labour market rewards prestige elements beyond the diploma (school networks, business sorting, region), the possibilities for equalising education are further weakened. The cumulative result is what many Japanese observers describe: the Parents' resources shape trajectories early, and the grade does not completely neutralize this beginning.

OED application in the Netherlands: silver spoons, fine levers

The shift towards the Netherlands and the OED lens clarifies a similar transformation, now anchored in the wealth and not only in test scores. Using administrative records that compare parents' wealth in 1992 with the wealth of their children around 2022, researchers find an increase of 3.2 percentiles in the ranking of children for each 10 percent increase in the parent class, resulting in a concentration in the top 1%. The dynamic has strengthened from 2006. The relationship is observed before great legacies, underlining the power of Transfers between living people, housing support, and educational investments, and not just legacies. The distributive scene is intense: the wealthiest 10% hold 56% and access to housing for young people is increasingly restricted. According to the OED, wealth is the Source Carrier, education is a Conversion Mechanism, and the destination is The Classification of Wealth, not just wages or jobs. The consequences are immediate: the mobility policy must be. At the same time, it targets the mechanisms of origin and the bottlenecks in education.

Mechanisms of reproduction: shadow training, early signals, and housing

Two mechanisms bridge the origin with the destination in both countries. First, the markets adjacent to education. In Japan, juku spending and selective exam ecosystems intensify the time and money parents invest. In the Netherlands, parental wealth buys Time (reduced student work), guidance, and Geographic Options close to selective programs, turning provenance into cleaner transfers and import wins—secondly, housing. Dutch administrative information shows that parental support is accelerating the transitions to home ownership, thereby accumulating assets and neighborhood impacts that feed into school quality and social capital. The Netherlands' top wealth structure and documented obstacles to leaving the paternal home strengthen these loops. These are Channels before inheritance: gifts, advance payment assistance, and pay-as-you-go teaching that move kids earlier and faster to high-performing positions. If we focus on legacies, we miss the fundamental points of policy lever: the Ongoing, complex transfers that run through childhood, screening in upper secondary education, and early adulthood.

What the data allows us to estimate: Transparent policy math on the back of the dossier

Where accurate figures are rare, we can still make transparent estimates to guide the design. Consider a Dutch Learning-Equality Voucher for low SES upper secondary students to purchase academically verified tuition or enrichment. Aim for 100.000 students – approximately reasonable if we meet the minimum income quintal in VMBO/HAVO/VWO – with 1,000 euros per student. Project Cost: 100 million euros, or about 0.01% of GDP, to 190 million euros. A similar size about GDP. The issue is not precise flexibility, but feasibility: 20% lifetime earnings and wealth effects. Japan juku-offset credit ¥ 30 billion. The moderate shares of GDP. They can strategically mitigate the most powerful conversion channels from origin to education. Assumptions are mentioned. The size orders are realistic.

From Principles to Practice: Five Levers That Move the OED

First transport before placing on the market. Because the Netherlands' parent-child wealth bond is strengthened before legacies, policy should aim at Flows between the living. Gradual donation tax exemptions linked to the EES and the beneficiary's purpose (education, first home equity) can reduce gaps without criminalising family assistance. Secondly, the transparency of selective admissions. Where selection in upper secondary or tertiary education is based on complex rubrics (tests, recommendations, extracurricular examinations), a public report of the differentiated acceptance and performance rates of the EES is required to identify and correct hidden obstacles. Thirdly, Targeted teaching and guidance. Evidence from both contexts shows that the benefits of education are accruing disproportionately to families who can afford. Public cofinancing reverses this slope. Fourthly, Housing Launch Bases. Extension of equity or public guarantee schemes for first-generation buyers to compensate for the gap in the advance payment. Fifthly, OED-aware accountability. Ministries should monitor origin-sensitive indicators of progress – e.g., trajectory change rates from SES, time to homeownership from parental wealth, and interquartile movement up to age 35 – to maintain policy aimed at the right joints in the mobility machine.

Predicting Reviews – and Refuting Them with Evidence

One critic says that the Netherlands remains broadly equal in education and that Japan, according to PISA fairness measurements, is "average", so the rhetoric overestimates the crisis. However, PISA itself shows that SES continues to explain performance, and the Dutch gaps in the SES are higher than the OECD average. Another criticism points to inheritance taxation: increase it, and the problem is solved. The Dutch evidence supports the opposite: Streets before inheritance dominate the outcomes of early adulthood, so the increase in inheritance taxes alone loses the Live Channels - gifts, housing assistance, and educational expenditures - that replicate the advantage. A third criticism concerns paternalism: why should parents be punished for helping their children? The answer is to Balance, not ban, subsidise aid for those without wealthy parents, make selective schemes transparent, and expand the public starting bases in housing and teaching. We have already socialized many risks. Here, we socialize a whole Inflow that creates opportunities to keep the value substantial.

The equalizer we need is politics, not prestige

If today's Netherlands shows that a child's wealth ranking at forty can be read by the parents' wealth class at twenty, and if Japan shows that the wealth ranking of a child in the age of forty can be read by the parents' wealth class at twenty, and if Japan shows that the wealth ranking of a child in the age of forty can be read by the wealth ranking of a child in the age of twenty, and if Japan shows that the wealth ranking of a child in the age of forty can be read by the wealth ranking of a child in the age of twenty, and if Japan shows that the wealth ranking of a child in the age of twenty can be read by the wealth of a child in the age of twenty. The degree no longer dispels its footprint. Origin, then we must stop treating school education as a universal Solvent. The OED triangle teaches a harder lesson: the origin flows through training at the destination, and the flow accelerates when shadow markets and housing barriers reward parents who can benefit upfront. To regain absolute mobility, states will have to attack at conversion points - Tuition funding, admission transparency, and first home equity – instead of reprimanding legacies after the fact. The goal is not to extinguish families, but to unclog paths where talent is suffocated from birth. If we fail, the matrix will continue to write our census tables. If we act, the following statistic we quote may be different: not the 96th percentile by birth, but the vast rise of those who started with little. This is the only balancer that still works – the politics.

The original article was authored by Esther Hamelink, a researcher at CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "The ‘silver spoon’ is becoming more important in the Netherlands" was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Araki, S. (2025). Education and Multidimensional Inequalities in Modern Japan. Sociology Compass. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.70072

CBS - Statistics Netherlands. (2025, January 15). 56% of wealth is in the hands of 10% of households.

CEPR VoxEU. Hamelink, E., Lejour, A., Schulenberg, R., &; van Essen, C. (2025, August 15). The 'silver spoon' is becoming increasingly important in the Netherlands.

CPB Dutch Office for Economic Policy Analysis. (2024, December 19). Een steuntje in de rug: Vermogensmobiliteit van ouder op kind [Helping hand: Intergenerational mobility of wealth].

DNB - De Nederlandsche Bank. Lee, G. (2022). Mortgage prepayments and tax-free intergenerational transfers (Working Document No 751).

Fujihara, S., &; Ishida, H. (2024). College is not the big equalizer in Japan. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 10. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231231225558

JASSO/MEXT. (2024–2025). Highlights of the International Student Survey (AY2024) and Basic School Research. Japan Student Services Organization. MEXT/NIC-Japan.

Matsuoka, R. (2024, December 17). Educational Inequality in Japan: Pre- and Post-Pandemic Trends and Recent Policy Developments. Discuss Japan.

OECD. (2023, December 5). PISA 2022 results (Vol. I): Country note—Japan. Paris: OECD Publications.

OECD. (2023, December 5). PISA 2022 results (Vol. I): Country note—Netherlands. Paris: OECD Publications.

OECD. (2023). OECD Economic Surveys: Netherlands 2023. Paris: OECD Publications.

Statistics Netherlands (CBS). (2024, June 19). Fewer young people can leave their paternal home.

Comment