Fragile East Asian Artery: Why Middle East Instability Endangers 30-40% of Our Industrial Production

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

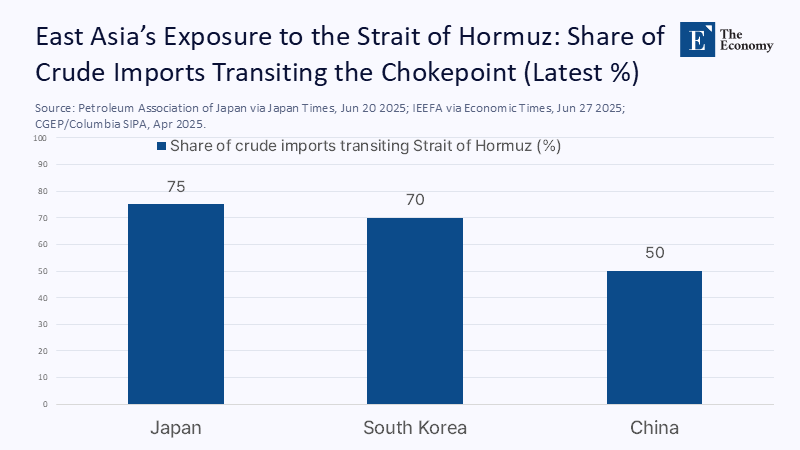

Twenty percent of the world's daily oil consumption is compressed through a single sea neck: the Strait of Hormuz. In 2024, this flow averaged around 20 million barrels per day and remained close to this level in early 2025. Closed or even severely disrupted, and the price shock would be immediate. The supply shock for Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and – albeit somewhat less – China will be structural. Japan's exposure is stark: about three-quarters of its crude oil imports naturally pass through Hormuz, and about 95% of its oil comes from the broader Middle East. South Korea's dependence remains in the 60-70 percent range, despite recent diversification toward America. Even China, protected by discounted Russian crude oil and the rise in gas through pipelines, still imports about three-quarters of its oil. When one-fifth of the world's supply depends on a few nautical miles, emergency planning can't be a footnote – it's the agenda.

From Japan's problem to the East Asian endurance test

The current policy framework often overlooks the interconnectedness of the East Asian system, treating the instability of the Middle East as a Japanese energy security problem with regional side effects. However, this is a dangerous oversimplification. Chokepoints, shipping insurance, and freight pricing dynamics starting in the Gulf have far-reaching implications throughout East Asia's integrated manufacturing base. Semiconductor logistics in Taiwan, petrochemical raw materials in Korea, and transportation fuels in China and Japan all drive the same tanker lanes and are all subject to the same market psychology. The Red Sea crisis from late 2023 is a stark reminder of how quickly maritime danger can spread to transportation costs, rerouting, and safety stockpiles. The Gulf is even more concentrated, making this a systemic problem for East Asia. Even schools, universities, and training systems are not immune: they rely on energy to heat buildings, move people, and operate data centres. Energy shocks have hit public budgets, student mobility, and the labour supply on which schools rely to operate.

Redefining the issue is essential now because adequate safety stocks must be designed before the crisis, not during it. East Asian governments are facing a paradox: oil prices in 2025 were relatively mild compared to 2022 highs, as the IEA forecasts a looming surplus. However, the risks from escalating conflicts remain significant and asymmetrical – especially for import-dependent Asia. Planning only for the baseline scenario generates complacency. Planning for the worst-case scenario without ignoring the baseline case is the only sensible route. Therefore, the right lens is the endurance tests: what if the flows through Hormuz are reduced for weeks, not hours? If premiums increase. If rerouting through the Cape of Good Hope becomes the norm. And if LNG cargoes are delayed when power demand peaks? These are not hypothetical scenarios, but potential risks that could have severe implications for East Asian energy security.

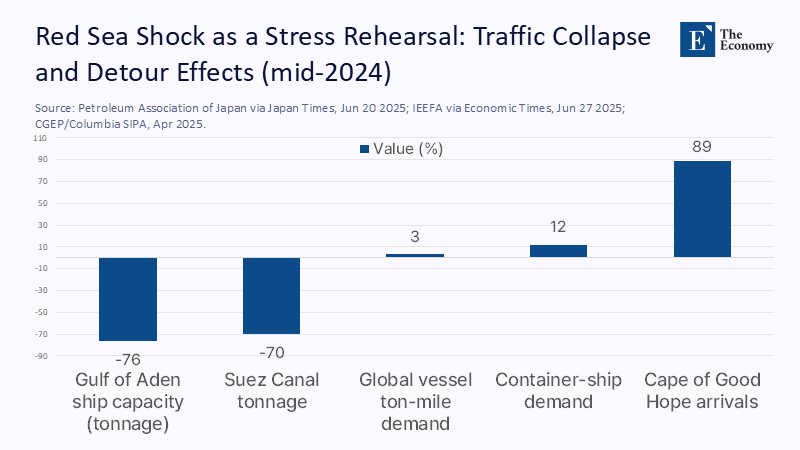

The choking points that bind

Two sea corridors connect East Asia with the energy of the Middle East: the Strait of Hormuz and, for some routes, the Bab el-Mandeb/Red Sea-Suez axis. Hormuz alone handles about one-fifth of the world's liquid oil and about one-fifth of the world's LNG, with Qatar's cargoes being particularly exposed. Even without a complete shutdown, harassment and repricing of insurance can move the markets. The Red Sea crisis from the end of 2023 offered a live demonstration: by mid-2024, the capacity of ships crossing the Gulf of Aden was reduced by 76% and the capacity via Suez was decreased by 70%, forcing Cape of Good Hope bypasses that increased global ship demand by 3% and container ship demand by 12%. Such bypasses add 10-14 days to Asia-Europe crossings, increase fuel use, and escalate inventory costs for East Asian manufacturers who already manage thin margins.

These logistical results are not abstract second-order details. They are first-class energy risks. Longer routes inflate crude delivery costs, squeeze refineries, and tighten the availability of naphtha, the "quiet foundation" of olefin and fragrance chains that supply plastics, fibers, and solvents. UNCTAD estimates show that bypasses increase demand for speech and increase emissions. Industry trackers recorded load spikes and higher fuel costs during peak holidays. Even when some traffic patterns smoothed out, the episode revealed how quickly capacity constraints translate into higher energy and input costs for Asia. These costs, in turn, are squeezing education budgets through utilities and transportation and reshaping the price of everything from lab reagents to on-campus food services. The sea map and the macroeconomic map are the same.

Who is exhibited and how: Japan, Korea, China, Taiwan

Japan is the regional extreme case in terms of concentration risk. About 95 percent of crude comes from the Middle East, with about three-quarters shipped via Hormuz. Recent trade data shows more than 95% of refinery raw materials from Middle Eastern suppliers in the 1st half of 2025, despite modest purchases from the United States. Japan's oil production is negligible, nuclear restarts are gradual, and LNG provides electricity, but it cannot quickly stop transport fuels or naphtha. The currency's weakness amplifies the vulnerability by making dollar energy more expensive in yen terms. In conclusion, the Tokyo Fair is immediate, mechanical, and challenging to compensate for financially fully.

South Korea's profile is similar, albeit with more visible diversification. The Middle East provided about 72% of its crude in 2023, but flows from the Americas reached record shares in about 2025 as Seoul actively rebalanced. Petrochemicals complicate the picture: Korea is the world's fourth-largest producer and Asia's top naphtha importer, making it highly sensitive to the cost and availability of raw materials. When the Red Sea or Gulf routes are wobbly, the flexible firecrackers can turn to more LPG, but the shift has limits. Korea's appetite for LNG – the world's third-largest buyer – also depends on maritime stability. Differentiation can reduce the risk. It cannot eliminate exposure to choking points.

Why "More Nuclear Energy" and "More Renewables" Don't Support Oil in a Deadline

East Asia's impressive nuclear fleet does not protect it from oil shocks. China operates about 60 reactors with dozens more under construction. South Korea runs 26; Japan has 33 operating units, but only a subset of these are online. Taiwan exited nuclear production in May 2025. These are significant numbers, but atomic power produces electricity, not liquid fuels. You can't put electrons in a chemical pyrolysis plant that requires naphtha as a feedstock, nor in marine shelters without retrofits and a fuel ecosystem that doesn't exist at scale. Electric vehicles can reduce demand for gasoline and diesel over time, but heavy trucks, shipping, and aviation remain oil-focused in the medium term. The region can be electrified faster, but electrification does not replace petrochemical raw materials or jet fuel overnight.

Renewables face the same borderline situation: they are excellent at displacing fossil electricity – and need to be developed faster – but do little for the molecules that produce plastics, solvents, coatings, and resins. Bionafta and synthetic fuels remain scarce and expensive. Hydrogen promises to be a reducing and fuel in steel and shipping, but timelines and infrastructure are measured in years, not months. The IEA's outlook for 2025 highlights a paradox: oil demand growth is slowing, and supply appears plentiful in 2026. However, a suffocation shock can crush the macroeconomic "surplus" with a local shortage. So, even with over a hundred reactors across Northeast Asia and rapid deployment of renewable energy, the region retains a heavy reliance on Middle Eastern oil – especially for transportation and petrochemicals – until substitutes escalate in both technology and logistics.

A 30-40% industrial production shock: a transparent scenario

The claim that East Asia will have to give up 30-40% of industrial production in a severe Gulf disturbance is not a prediction. Here's a conservative path. Let's assume a six-week period in which Hormuz traffic is reduced by 50% due to persistent harassment and the withdrawal of insurance, according to the historical dynamics of the "tanker war" before the complete shutdown. This removes about 10 million barrels per day export capacity from the global market. Because Japan supplies ~95 percent of its crude from the Middle East, Korea ~60-70 percent, and Taiwan a large share, we estimate immediate shortages of delivered barrels unless offset by strategic stockpiles, emergency exchanges, and long-distance reroutes. In the short term, the elasticity of global oil demand is close to -0.1, so price increases have little effect on clearing the markets quickly. Volume restrictions dominate.

Map these shortages in industrial production through two channels: first, transport fuels: trucks and coastal shipping transport intermediate goods; Voucher distribution reduces factory use; second, raw materials: naphtha shortages limit the production of ethylene and propylene, which diffuse into plastics, fibers, and packaging - inputs into electronics, automobiles, and consumer goods. Korea's petrochemical capacity is a global hub. Limit the crackers and the ripples spread. With inventories typically measured in weeks, not months, we estimate that a persistent 20-25% reduction in available liquid fuels and naphtha in Japan and Korea would force a 15-20% reduction in manufacturing use, boosted by logistics and spillovers. The pressure layer in the energy sector from delayed LNG cargoes and higher spot prices, and a reasonable, cumulative industrial production blow for the region reaches 30-40% at maximum pressure over a six-week horizon – mitigated by stock withdrawal and substitution, but still economically brutal. Methodologically, we combine chokepoint flow data, import aggregation, short-term elasticities, and supply chain multipliers derived from petrochemical capacity and transport intensity.

A Strategy Manual for the Education Sector and a Regional Leadership Mandate

If energy security is a risk to the system, the education sector needs a system response. Ministries and university systems should treat fuel and energy as critical inputs and pre-contract for resilience. First, campus microgrids with storage, backup dual diesel-LNG fuels, and demand response protocols can keep critical services alive during distribution. Second, procurement consortia across public universities can offset electricity and LNG exposure together, flattening price spikes, while ministries establish "education critical load" reserve allocations as well as hospital protection. Third, emergency schedules – heat adaptation schedules, hybrid teaching with protected lab time, and transition priority for vocational training and teacher training programs – can preserve learning while reducing maximum fuel use. Each measure is most effective when rehearsing exercises, not panicking.

Japan should lead a Northeast Asian Energy Continuity Pact with Korea and, where possible, with China and Taiwan – precisely because Tokyo is more exposed. The Pact's work lines should include standard emergency protocols for strategic oil reserves; coordinated long-distance crude oil planning from the Americas and West Africa during strain; convoy or maritime escort policies for tankers transporting liquefied natural gas and crude oil in high-risk areas by international law; and an "exchange line" of petrochemical raw materials to prioritize medical supplies, food packaging, and education-critical supplies. Parallel diplomacy matters: leveraging Japan's unique ties in the Gulf to reduce miscalculation and mobilizing the G7, ASEAN, and East Asia Summit forums to secure maritime transit. In the likely baseline scenario of abundant supply and milder prices, these possibilities will appear to be overinsurance. In the queue, they will look like a prediction.

Anticipating the obvious criticism – and why it fails

Criticism: If the IEA expects oversupply in 2026 and Brent has traded well below 2022 highs, isn't all this overreaction? Only if we confuse price with safety. The IEA's outlook makes it clear that demand is softening and storage is plentiful – until it isn't. Marine risk is binary at the point of impact, but continuous in terms of its effect on prices. Insurers do not wait for a blockade to reprice the risk of war. As the Red Sea episode has shown, rerouting alone substantially increases costs, even when oil is abundant overall. A disruption of Hormuz could coexist with a "surplus" on paper and a shortage at the refinery gate in Yokohama or Ulsan. The oversupply narrative and the chokepoint narrative are not contradictions. They are parallel truths. The smart contract buys insurance downwards while reaping upward savings from today's prices.

Artery and Selection

A single artery transports one-fifth of the world's oil through water, where a miscalculation can become a macroeconomic fact. East Asia is the final instrument of this artery. Japan is at the forefront of the danger curve because its crude is so concentrated and so exposed to Hormuz. Korea and Taiwan are not far behind. China is somewhat protected from Russian barrels and gas through pipelines, but it is still dependent on oil imports. We have alternatives, but not at the speed of a crisis: nuclear power and renewable energy are decarbonising electrons. They cannot create molecules for petrochemicals and jet fuels on demand. The choice is not between panic and passivity, but between improvisation and preparation. Create a regional continuity pact now. Pre-wiring the education sector for energy shocks; Use today's relative peace of mind price to buy physical and institutional insurance. If the tail risk never bites, we will have paid a modest premium. If that happens, these six weeks will test—and define—the resilience of East Asian economies and its classes.

The original article was authored by Mitsuhisa Fukutomi, a Professor of International Politics at the Institute for the Study of Social Sciences, Hitotsubashi University. The English version, titled "Japan must lead on Middle East instability," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Business Insider (2025, June). "Because all eyes are on the Straits of Hormuz..."

Center on Global Energy Policy, Columbia SIPA (Downs, E.). (2025, April 30). China's oil demand, imports and security of supply.

External Relations Council (2025, January 2). "China and Russia deepen energy ties..."

Energy Information Management (EIA). (2023, November 21). Global oil transit bottlenecks.

Energy Information Service (EIA). (2025, June 16). "Amid regional conflicts, the Strait of Hormuz remains critical..."

Energy Information Service (EIA). (2025, February 11). "China's crude oil imports fell by a record..."

East Asia Forum (Fukutomi, M.). (2025, August 14). Japan must lead the instability in the Middle East.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2025, Aug). Oil Market Report – August 2025.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2025, June 17). Oil 2025: Analysis and forecast to 2030.

Japan Times (2025, June 20). "Japan's economy is particularly vulnerable amid conflicts in the Middle East."

METI (2025, Aug). Import of crude oil by source (statistical PDF).

Reuters (2023, October 26). "How great is Japan's dependence on Middle Eastern energy."

Reuters (2025, January 20). "China's crude oil imports from top supplier Russia reach a new high in 2024."

S&P Global Commodity Insights (2025, August 5). "Japanese refineries recognize the need to reduce dependence on the Middle East by 95 percent."

UNCTAD (2024, October 22). Overview of maritime transport 2024.

UNCTAD (2024, February). Navigation in Rough Waters: Impacts on World Trade from Disruption of Shipping

World Bank (2025). The deepening of the Red Sea maritime crisis. World Bank

Nuclear Union (2025). Nuclear power in China; nuclear power in Japan; nuclear power in South Korea; Nuclear power in Taiwan.

World Nuclear News (2025, May 19). "The closure of the reactor signals Taiwan's nuclear exit."

Comment