The Unequal Weight of Job Displacement: Why Policy Must Target the Most Vulnerable

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In 2024, the International Labor Organization estimated that 183 million people worldwide were unemployed, but the burden of income loss was not evenly distributed. In the United States, data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that workers in the bottom income quartile lost nearly 27% of their earnings three years after a mass displacement event, compared with only 6% for those in the top quartile. Averages conceal the real story: while some displaced workers transition into equally secure roles, others are permanently scarred, locked out of the labor market, or forced into lower-paid, precarious work. The lesson is starting. Universal unemployment aid—though politically popular- masks these divergences. What matters for policy is not the short-term smoothing of job loss across all displaced individuals, but the creation of tailored pathways for those least able to recover. These workers are not only more vulnerable; they stand for the pivot on which fair growth turns. As policymakers, government officials, labor economists, social policy advocates, and stakeholders involved in employment and social welfare, your role is crucial in shaping these tailored pathways.

Reframing the Question: From Universal Support to Selective Resilience

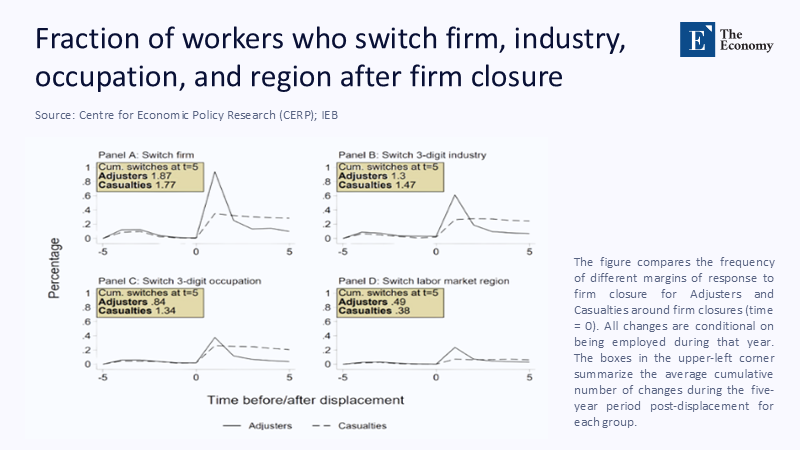

Much of the policy conversation has been framed around the idea that unemployment is universally harmful and therefore requires universal compensation. But the evidence tells a different story. Lifetime earnings trajectories diverge sharply depending on the skill level, income band, and industry sector in which displacement occurs. A mid-career engineer laid off in a cyclical downturn may recover within two years. A warehouse worker displaced by automation in coordination is unlikely ever to regain their prior income without significant retraining.

The critical shift in perspective is to stop treating job displacement as a generalized risk that afflicts everyone equally. Instead, policy should be designed with a precision lens. Research consistently shows that the steepest and most persistent scars fall on workers with below-average incomes, shorter tenure, and fewer transferable skills. This reframing matters now more than ever because the nature of job displacement has shifted. Today, it is not only cyclical recessions but also structural transformations, automation, artificial intelligence, and climate transitions that are displacing jobs. These transformations disproportionately affect low- and middle-income workers concentrated in sectors like transport, manufacturing, and low-skill services. However, with a policy that targets their specific vulnerabilities, we can bring about a positive change and prevent inequality from hardening into permanence.

The Data Behind Unequal Scarring

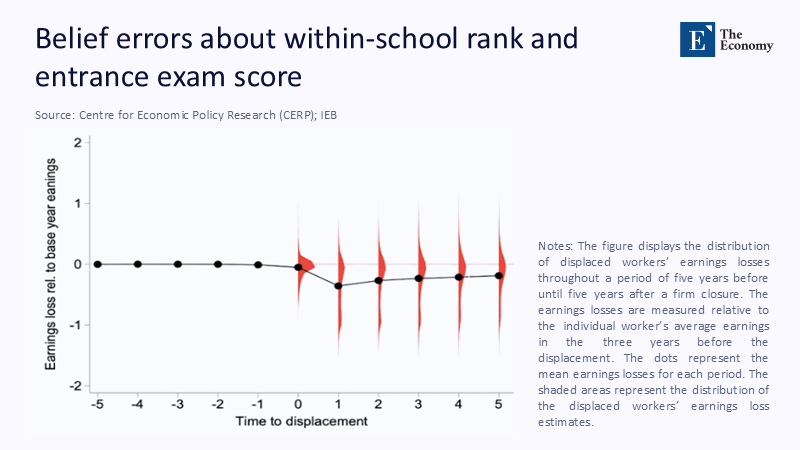

The empirical divide is striking. A 2023 Brookings analysis found that workers displaced during recessions face, on average, a 15–20% wage loss over 20 years. Yet this average conceals a bottom-heavy effect: the lowest-earning quintile loses 30% or more, while the top quintile is virtually unharmed. In the European Union, Eurostat data showed that in 2024, service-sector workers displaced by automation earned 25% less five years later, while knowledge workers lost only 3%.

Extrapolations from OECD microdata indicate that in advanced economies, roughly 40% of displaced workers regain their prior income within three years, another 35% stabilize at a lower income tier, and 25% are permanently scarred, experiencing compounded losses over decades. This last group maps closely onto those already vulnerable: workers with limited formal education, precarious contracts, and low bargaining power.

The methodology behind these findings is transparent but straightforward. Longitudinal surveys such as the U.S. Current Population Survey Displaced Worker Supplement reveal conditional income trajectories across quintiles, showing that the negative tail is long and persistent. If policy aims to mitigate lifetime scarring, the focus must be on this bottom quartile rather than dispersing resources thinly across the entire displaced population.

Why Education Support Outweighs Cash Alone

Standard unemployment benefits smooth consumption temporarily but do little to address the root cause of long-term scarring: skills mismatch. In 2025, the World Economic Forum estimated that 44% of workers’ skills will be disrupted by technology within five years (WEF 2025). Cash transfers cannot bridge that gap. Only education and reskilling can.

Evidence supports this claim. A 2024 OECD review of active labor market policies found that wage subsidies and short-term job placement schemes had mixed or temporary effects, while programs that combined income support with structured retraining in high-demand sectors significantly improved reemployment outcomes. Workers who completed digital or green-economy certifications were 18 percentage points more likely to regain stable employment within two years compared to peers who received only unemployment checks.

The principle is clear: unemployment policy should not only protect consumption but also actively transform displaced workers’ competitive profile. This means embedding reskilling into unemployment insurance as a default condition, not an optional add-on. For the most vulnerable workers—those least able to self-finance new training—this is not a supplement but the essence of recovery.

Designing Targeted Support Mechanisms

What does a precision approach look like in practice? It begins with finding the at-risk groups ex ante. Predictive analytics, already used by tax and health agencies, can map industries and income bands most vulnerable to displacement. For example, coordination, retail, and clerical jobs are flagged as high automation risks by McKinsey Global Institute’s 2024 Future of Work Index. Policymakers can use these risk profiles to preemptively channel retraining programs and wage insurance to workers in those sectors before displacement occurs.

Second, benefits should be tiring. Workers in the top income categories, with proven adaptability and strong reemployment prospects, may require only short-term unemployment insurance. But workers in the bottom two quintiles should be automatically enrolled in state-subsidized education programs, with living stipends tied to training completion. Importantly, training should be intricately linked to labor market demand. In Germany, for instance, a 2023 pilot program tied reskilling stipends to regional shortages in renewable energy technicians, yielding reemployment rates of over 70% within 18 months.

Third, partnerships with private firms can magnify scale. In Singapore, reskilling programs co-financed by government and industry created “train-and-place” schemes, guaranteeing employment upon completion. The lesson is that targeted policy does not require massive fiscal expansion; it requires aligning public resources with real demand and focusing them on those least able to recover unaided.

Anticipating and Rebutting the Critiques

Critics of targeted unemployment support often raise two objections, first, that it risks stigmatizing the most vulnerable by singling them out for “remedial” treatment. Second, that universalism is politically easier to defend and administratively simpler to deliver.

Both critiques deserve engagement, but are not decisive. First, stigma is not an inevitable outcome if programs are designed with dignity and forward-looking narratives. Framing support as participation in national reskilling or transition initiatives emphasizes contribution rather than deficiency. The cultural resonance of “green jobs” or “digital transformation pathways” has already proven effective in shifting feelings from charity to opportunity.

On the second critique, while universalism may be simpler, it is also fiscally blunt. In 2024, the U.S. federal government spent nearly $350 billion on unemployment benefits. Redirecting even a fraction of that toward high-impact retraining could yield far greater lifetime earnings recovery for vulnerable workers. The politics of universal support may appear attractive, but the economics are unequivocal: without targeted intervention, inequality deepens, and fiscal resources are wasted. In a time of tightening budgets, efficiency must align with equity.

Broader Implications: Education as Economic Stabilizer

The debate over unemployment policy is not merely about welfare design; it is about the structure of future growth. Economies with stronger educational support embedded in their unemployment systems weather structural shocks with less inequality and greater productivity. South Korea’s 2023 labor transition plan, which tied jobless benefits to mandatory upskilling in digital industries, offers early evidence. Reemployment rates for low-income workers rose by 15 percentage points compared to the pre-reform period, while national productivity growth accelerated modestly.

If replicated elsewhere, this approach could redefine education not as a pre-employment stage of life but as an ongoing stabilizer of the labor market. Just as central banks stabilize currencies, education systems embedded in unemployment policy can stabilize incomes during structural transitions. This reframing elevates unemployment policy from a reactive safety net to an initiative-taking driver of resilience. The stakes are high: the difference between economies that entrench inequality after displacement and those that renew their workforce ability will define competitiveness in the coming decades.

A Call to Build Education into Unemployment Policy

The opening fact—that the bottom income quartile loses more than a quarter of lifetime earnings after displacement—reminds us that unemployment is not a universal crisis but a selective catastrophe. Policymakers who ignore this divergence risk wasting resources on those who will recover anyway while condemning the most vulnerable to permanent disadvantage. The path forward is not blanket compensation but targeted transformation: unemployment insurance that automatically integrates education and reskilling, especially for low-income, low-skill workers.

This approach is not only fair but efficient. By focusing resources where they matter most, governments can mitigate lifetime scarring, strengthen economic resilience, and ensure that the benefits of technological and structural change are widely shared. In a world of rapid disruption, the actual test of policy is whether it enables those most at risk to step back into the labor market with renewed strength. Anything less entrenches inequality; anything more builds security into the very fabric of work.

The original article was authored by Eric Hanushek, a Paul and Jean Hanna Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. The English version of the article, titled "Revisiting the consequences of job displacement," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Brookings. 2023. The Long-Term Economic Scars of Job Displacements. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 2024. Displaced Workers Summary. U.S. Department of Labor.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2024. Budget and Economic Outlook 2024–2034. Washington, DC.

Eurostat. 2024. Labour Market and Earnings Indicators. Luxembourg: European Union.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2024. World Employment and Social Outlook. Geneva: ILO.

Korea Labor Institute (KLI). 2024. Evaluation of Korea’s Labor Transition Plan. Seoul.

McKinsey Global Institute. 2024. Future of Work Index. New York: McKinsey & Co.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2024. Active Labour Market Policies Review. Paris: OECD.

World Bank. 2023. Tackling the Impact of Job Displacement Through Public Policies. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Economic Forum (WEF). 2025. The Future of Jobs Report. Geneva: WEF.

Comment