Keep the Lanes Open: Why the World Should Trade Through America's Tariff Storm

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

The most critical numbers in the global economy this year do not come from Wall Street indices or quarterly GDP prints. They are the $33 trillion that global trade reached in 2024—the highest on record—and 0.2%, the World Trade Organization's 2025 forecast for world merchandise trade growth once new tariff measures are fully factored in. Read together, these numbers tell a simple story with complicated policy consequences: the trading system is still functioning at scale, but one country's tariff shock is strong enough to shave the world's momentum. History offers a warning and a guide. After the 1930 Smoot–Hawley tariff helped crush world commerce, the 1934 Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA) began rebuilding openness and shaped the post-war GATT. We face a similar fork. The United States can choose protection; the rest of the world can—and should—keep the lanes open, deepen regional and plurilateral links, and buttress the multilateral architecture so the next U.S. administration can reverse course without the world having drifted into hard blocs.

Reframing the Debate: Free Trade Isn't Broken—It's Being Localized

The conventional reading of the tariff wave is alarmist: if the largest economy turns inward, the free-trade era that began with the 1994 Uruguay Round is over. That misreads both economics and institutional reality. What has changed is not the existence of an open trading order but the geography of the shock. This is a North America–anchored tariff surge, not a universal embargo. The world's response should not be a race to copy U.S. policy, but a disciplined choice to trade through the disruption—maintaining most-favored-nation (MFN) openness where possible, building redundancy in critical supply chains, and preserving the regulatory and dispute-settlement habits that let the next U.S. pivot back without prohibitive costs. The interwar lesson is blunt: unilateral hikes breed retaliation and collapse; reciprocal bargains rebuild confidence. The RTAA's shift from congressional tariff lines to executive agreements—and MFN extension—was the hinge that made GATT feasible. That template still applies.

A second reframing is political. Contemporary tariffs are often sold as a way to "punish China," or to fix bilateral deficits. But unilateral levies do not remake value chains—rules do. If others keep rules predictable, the opportunity cost of bloc formation rises for firms and universities that depend on cross-border scale. Asia's policymakers have already internalized this logic. The region's priority, as scholars have noted, is to keep Asia open to trade and investment while navigating U.S. policy turbulence—not to build walls that would fragment production networks that took decades to assemble. This is not about indifference to security concerns; it is about refusing to universalize one country's tariff strategy into a new global norm.

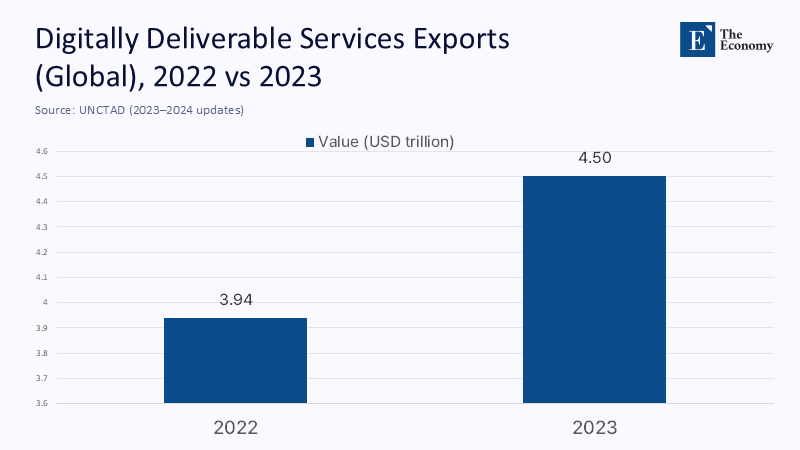

What the Numbers Say: The Global Trade System Shows Resilience Despite a U.S.-Centered Shock

The data show a trading system that bent, but did not break. UNCTAD estimates that global trade expanded 3.7% in 2024 to an all-time high, propelled by services and by developing economies. At the same time, the WTO expects merchandise trade to be flat-to-negative in 2025 once tariffs and uncertainty filter through supply chains, with the strongest downdrafts in North America—precisely where policy has shifted most. Services trade, by contrast, continued to expand by 6.8% in 2024, and the fastest-growing segment—digitally delivered services—has quadrupled since 2005, reaching roughly $4.25–$4.64 trillion in 2023–24. In short, the tradable economy is pivoting toward bits over tons, a metaphor for the increasing importance of digital services over physical goods, and bits cross borders more easily when rules are stable.

Investment is the soft underbelly. Global FDI fell by about 2% in 2023 and was weaker once conduit flows are stripped out, reflecting a wait-and-see world. In this environment, policy clarity substitutes for subsidies. That is why decisions like the WTO's 2024 extension of the moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions to 2026 matter far beyond Geneva; they are a floor under the fastest-growing part of trade. Meanwhile, unilateral tariffs have been formalized in the United States via executive actions and orders, with Washington asserting a broader "reciprocal tariff" authority. The rest of the world should treat these measures as localized frictions, which are specific trade barriers that affect a particular region or industry, not a new constitution.

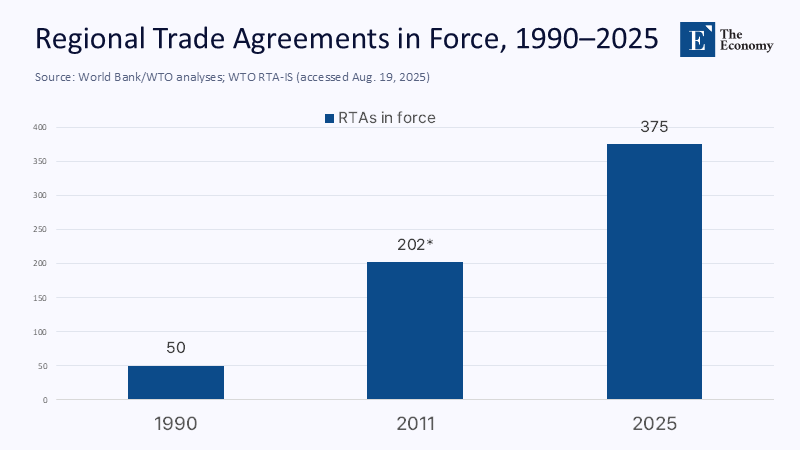

The Operating System of Openness: Regional and Plurilateral Deals Are Doing the Work

While headlines fixate on U.S.–China tariffs, the architecture of openness keeps evolving elsewhere. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) entered into force for the United Kingdom on Dec. 15, 2024, expanding coverage across the Pacific. The EU–New Zealand FTA took effect May 1, 2024, and the EU–Kenya EPA began bilateral application July 1, 2024, underscoring how like-minded partners continue to prune tariffs and codify modern digital and sustainability disciplines. In parallel, RCEP, now entirely in force, blankets roughly a third of world GDP and trade, anchoring low-friction Asian supply chains. These initiatives do not replace the WTO; they complement it, preventing a race to blocs by giving firms predictable cross-border rules even as Washington experiments.

Africa's integration push is the other under-reported story. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), a free trade area among 54 of the 55 African Union nations, continues to advance from legal text to lived trade: tariff schedules are being implemented, rules of origin finalized, and the Guided Trade Initiative expanded beyond the first movers. Even if only a couple of dozen countries are actively shipping under AfCFTA preferences today, the direction of travel is clear; with each ratification, intra-African trade gets easier, and firms gain a continental market. That matters for global openness because it reduces reliance on any single external pole and deepens South-South links that were fragile in the last era of tariff wars. The more such deals are operationalized, the less oxygen remains for hard bloc formation.

Knowledge Is a Traded Good: Protecting the Education–Research Supply Chain

Education is not just a public service; it is a tradeable ecosystem of people, services, and scientific inputs. In services statistics, "education-related travel" moves with visas and affordability; in the lab, tariffs on specialized equipment, export controls, and uncertain licensing raise the cost and time of discovery. WTO economists explicitly flag that policy uncertainty can dent education-related travel; data from nature show a shifting geography of research output and collaboration, with Asia's share rising quickly. The combination is simple: visa-light, tariff-light systems produce more science per euro. For university administrators and funders, the policy translation is to hedge against unilateral shocks by growing triangulated collaborations—for example, Europe–Asia–Africa consortia with shared IP protocols and dual lab sites for sensitive equipment.

The digitalization of learning compounds the stakes. Digitally delivered services—from software to professional and creative services—now exceed $4.5 trillion globally and are the fastest-growing component of cross-border exchange. Universities are both producers (cross-border micro-credentials, executive education, ed-tech spinoffs) and consumers (cloud, compute, data services) of that trade. Extending the e-commerce moratorium was therefore a direct protection of the sector's arteries; letting it lapse in 2026 would invite a patchwork of download tariffs on courseware, cloud computing, data transfers, and even streaming lectures. Education ministries and rectors should press their trade counterparts to lock in a plurilateral moratorium if multilateral consensus falters, and to include research-and-education carve-outs in regional deals. Hence, knowledge flows remain insulated from tariff theatrics.

Avoiding the Bloc Trap: Security Where Needed, Openness by Default

The legitimate language of "economic security" is being stretched to cover everything from advanced chips to aluminum nails. Overreach invites retaliation and, if copied widely, hardens blocs. The quantifiable downside is non-trivial: OECD and IMF simulations suggest that deep geoeconomic fragmentation can impose multi-percentage-point losses on global GDP and double-digit drops in trade volumes in affected regions. The correct doctrine is guardrails, not walls. That means narrow, risk-proportional controls on truly sensitive technologies; transparent screening of inward investment; and the use of trade defense instruments against demonstrable subsidy-linked injury—without translating those tools into general tariffs. The wider the carve-outs, the smaller the bloc effect.

Enforcement should be smart, not reflexive. The United States has already telegraphed a more aggressive posture on transshipment and rules-of-origin gamesmanship in response to its tariff ladder; that is, Washington's choice. Others should respond not by hiking across-the-board tariff walls but by tightening origin verification, investing in data-driven customs, and cooperating on sanctions-adjacent evasion where needed. The goal is to police the edges without choking the commons. Suppose partners can demonstrate that low-friction trade is not a vector for leakage. In that case, political space widens to keep general tariffs low—and to show domestic constituencies that openness can be defended without capitulation.

A Plan B Worth Having: If Blocs Emerge, Build a "GATT 2.0" for the Non-Aligned

Prudence demands a contingency. If the world does tip toward bloc economies, the mistake would be to wait a decade for a new Uruguay Round. Countries that prefer openness should assemble a GATT 2.0-style platform with three immediate features. First, a standing Open Lanes Pact: zero tariffs on knowledge-intensive goods and services—education, research equipment, scientific publications, cloud and compute, standards testing—paired with expedited visas for students and scientists. Second, a plurilateral digital moratorium, binding among signatories beyond 2026, to prevent a world of "download duties." Third, a fast-track dispute and transparency panel—leaner than the WTO's appellate body, but with deadlines and public reasoning—to keep trust high while the larger system resets. None of this requires abandoning the WTO; it buys time and keeps the non-aligned world interoperable.

In designing that Plan B, we should borrow the RTAA's political technology. The RTAA's genius was to lower tariffs reciprocally through executive agreements and extend MFN concessions, depoliticizing line-by-line fights and creating constituencies for openness. A modernized version—focused narrowly on knowledge and digital trade—could be negotiated quickly among willing partners in Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America. At every step, the door should remain open for the United States to re-enter on unchanged terms; the point is not to punish America, but to discipline the incentives so any future U.S. administration can pivot back into an order that never fully fractured.

What Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers Should Do Now

Universities should treat trade policy as infrastructure. Budget for tariff and compliance risk on lab equipment; diversify procurement away from single-jurisdiction choke points; and negotiate dual-site research projects that allow sensitive apparatus to be located where export controls permit, with mirrored teams elsewhere to protect continuity. Admissions teams and ministries should anticipate volatility in education-related travel by expanding co-taught, cross-border degree modules and credential recognition pacts, ensuring that a visa squeeze in one hub does not derail degree pathways. Finally, national policymakers should hard-wire education and research carve-outs in regional and bilateral deals, and prioritize quick adoption of digital trade chapters that preserve data flows, intermediate liability protections, and standards cooperation relevant to ed-tech and scientific collaboration. These are not luxuries; they are the scaffolding that keeps ideas moving when politics turns episodically inward.

Regulators have a complementary role. Where export controls are justified, they should be narrowly scoped, time-limited, and reviewable; where tariffs create perverse incentives (for example, encouraging gray-market transshipment of lab components), customs authorities should coordinate with universities and accredited research consortia to develop trusted research importer schemes—fast lanes that preserve compliance and speed. Education ministries can also co-fund compute credits and shared cloud infrastructure for public universities to mitigate any cost pass-through if digital duties emerge in 2026 in jurisdictions outside the moratorium. At the multilateral level, governments that want openness should table a Knowledge Trade Arrangement at the WTO—an open plurilateral anchored in existing disciplines—to make explicit what has long been implicit: knowledge is tradable, and its free flow is a public good.

Keep the Lanes Open

The last time the world flirted with tariff chaos, the United States invented a new politics of openness and laid the groundwork for fifty years of the GATT. We are not there yet; the trading system still moves $33 trillion worth of goods and services, and much of the world is signing—not shredding—agreements. But the pessimistic growth forecast in goods trade for 2025 is the early warning that policy can overpower fundamentals. The way forward is to refuse imitation. Let Washington run its experiment; the rest of us should thicken the tissues of exchange—regional deals, digital moratoria, knowledge carve-outs—so that economies, universities, and labs can keep working while the political weather changes. If blocs do harden, we have the legal and historical tools to build a GATT 2.0 that keeps the non-aligned interoperable. Either way, the task is the same: keep the lanes open so the next pivot back to openness is a bridge, not a rebuild.

The original article was authored by EAF editors. The English version, titled "Keeping Asia open to trade and investment amid Trump's tariff chaos," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Atlantic Council. (2021). How Donald Trump remade global trade. New Atlanticist.

El País. (2023, Sept. 26). Geoeconomic fragmentation getting worse and could lead to loss of 5% of global GDP in long term, OECD warns.

European Commission. (2024, May 1). EU–New Zealand trade agreement enters into force.

European Commission — Access2Markets. (2024, Jul. 1). Bilateral application of EU–Kenya Trade Agreement on Jul. 1 2024.

France 24. (2025, Aug. 1). Trump orders tariffs on dozens of countries in push to reshape global trade.

International Monetary Fund. (2023). The rise of discriminatory regionalism (M. Ruta). Finance & Development.

Nature Portfolio. (2025, Jun. 11). Nature Index Research Leaders 2025: Press release.

U.K. Government. (2024, Dec. 5). UK counting down to CPTPP entry into force.

U.K. Government. (2024, Aug. 29). UK to join CPTPP by Dec. 15 2024.

UNCTAD. (2025, Mar. 14). Global trade hits record $33 trillion in 2024, driven by services and developing economies.

UNCTAD. (2024, Dec. 6). Developing economies surpass $1 trillion in digitally deliverable services exports; global total $4.5 trillion.

UNCTAD. (2024, Jun. 20). World Investment Report 2024: Investment facilitation and growth amid crises.

U.S. Office of the Historian. Protectionism in the interwar period.

U.S. Office of the Historian. New Deal trade policy: The Export–Import Bank & the RTAA, 1934.

U.S. White House. (2025, Jul. 31). Further Modifying the Reciprocal Tariff Rates. Presidential action.

WTO. (2025, Apr. 14). Global Trade Outlook and Statistics 2024–2025.

WTO. (2024, Mar. 1). MC13 ends with decisions on dispute reform and e-commerce moratorium extension to 2026.

WTO RTA-IS. (2025). Number of regional trade agreements in force (RTA Tracker).

Comment