Build Advantages, Not Walls: An Innovation-First Trade Strategy for the United States

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

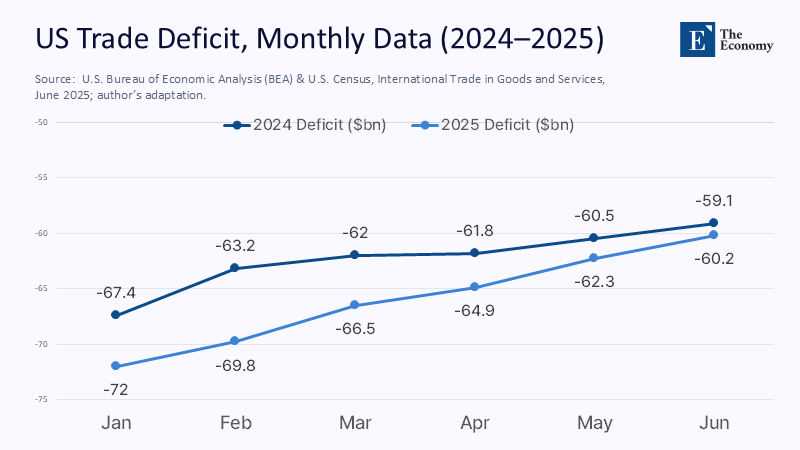

Each tariff schedule can be encapsulated by a single figure: the expenses incurred by households and businesses. By the spring of 2025, the Richmond Fed projected that new policies had raised the average effective tariff on imports from China to approximately one-third of their value, while China's portion of US imports had already decreased from 22 percent in 2017 to around 13–14 percent in 2024. This combination increases the overall cost of goods for Americans without addressing the fundamental issue: a lack of products that the global market is willing to pay extra for. At the same time, the WTO’s outlook from April 2025 warns that ongoing rounds of reciprocal tariffs and political uncertainty could lead to a downturn in anticipated trade growth for 2025, with the most significant impact felt in North America—again, a cost borne at home. The U.S. trade report for June 2025 reveals a deficit of $60.2 billion and a widening gap compared to 2024, reinforcing a lesson we continually learn: tariff maneuvers cannot replace the need for establishing a genuine, lasting comparative advantage.

From Deficits to Advantages: Reframing the Target

Trade deficits are accounting outcomes of macroeconomic choices—national saving, investment, and fiscal stance—not a scoreboard of national failure. Using bilateral deficits as a compass for policy leads to the wrong destination because it confuses where we buy with what we’re good at selling. The fixation on “reciprocal” tariffs tied to bilateral gaps ignores supply chains, services surpluses, and the dollar’s role; more importantly, it neglects the engine of export power: product quality rooted in technology and skills. If we want sustainable bargaining power, we need a productivity strategy, not a customs strategy. The policy question should be: what mix of innovation, skills, and scaling capacity lets firms command margins abroad and pay middle-class wages at home? That lens flips the conversation from closing gaps to opening markets, by making things that global buyers cannot easily substitute.

Bilateral tariffs can look rhetorically decisive and still be economically self-undermining. They raise input costs on domestic producers embedded in global value chains, dampen investment with policy uncertainty, and invite retaliation that shrinks the very markets U.S. exporters need. IMF and WTO analyses in 2024–2025 show that geoeconomic fragmentation—of which escalating tariffs are a key channel—imposes persistent output losses and depresses merchandise trade. In short, a deficit-targeting tariff is a policy for managing symptoms, while an advantage-building strategy is a policy for changing fundamentals. The latter requires patience and reform; the former offers headlines and, frequently, higher prices.

What the New Numbers Say

The latest official trade release puts the June 2025 U.S. goods-and-services deficit at $60.2 billion, down month-to-month but up sharply year-to-date versus 2024 as imports outpaced exports. The detail matters: the goods deficit narrowed in June, the services surplus ticked up, and the real (inflation-adjusted) goods deficit fell—yet the aggregate gap widened over the first half of the year. The message is not that tariffs “failed” in a simple sense; it is that deficits move with oil, the dollar, the cycle, and fiscal policy as much as with border taxes. Treating the monthly gap as a policy grade is like grading a physics experiment by the color of the beaker.

More telling is the composition of imports. China’s measured share of U.S. imports fell to roughly 13–14 percent in 2024, with Mexico becoming America’s top supplier. Still, the New York Fed cautions that the decline is overstated in official data because of rerouting through third countries. That nuance matters for policy design: blunt tariffs risk paying more for the same Asian value chains with extra paperwork attached. At the same time, Richmond Fed economists show how the average effective tariff (AETR) spikes when new, uniform surcharges stack atop existing duties—especially on China—raising the tax wedge on a large mix of intermediate goods. The better reading of these data is not that “decoupling worked,” but that supply chains adapted while costs rose, and that adaptation is path-dependent and slow to reverse.

How Tariffs Tax Learning—and Why Skills Are the Scarce Input

Who pays for tariffs? Updated syntheses of the 2018–2019 shock, the closest laboratory we have, find that U.S. firms and consumers bore most of the costs, with pass-through into import and often retail prices near full. Newer work in 2023 emphasizes the asymmetry: U.S. importers absorbed roughly 90 percent of the burden of U.S. tariffs, while Chinese importers bore a smaller share of China’s retaliation. That incidence profile is not just about prices; it’s about learning. When intermediate inputs cost more, firms cut experimentation, slow product refresh cycles, and defer adoption of frontier equipment, particularly among smaller manufacturers. Tariffs are a tax on the very process by which firms climb quality ladders.

A second constraint is human capital. The 2024 international PIAAC release shows U.S. adults underperforming OECD peers in numeracy and adaptive problem solving, with concerning shares at the lowest proficiency levels. At the same time, manufacturers project millions of skilled vacancies through the next decade. Put differently, the binding constraint on a broad-based manufacturing renaissance is not just “cheap foreign widgets,” but domestic capacity to absorb advanced processes at scale. If we use tariffs to inflate costs while neglecting the workforce that turns machines into margins, we are taxing learning and underfunding the learners. An education-centered trade strategy would invert those priorities.

A Back-of-the-Envelope: What the Current Tariff Mix Implies

Here is a transparent estimate, using published parameters to illustrate orders of magnitude. Suppose the average effective tariff on Chinese goods rises to ~33.5 percent (Richmond Fed scenario) and China supplies ~13.8 percent of U.S. goods imports (2024). The first-round, import-weighted price wedge is roughly 0.335 × 0.138 ≈ 4.6 percent on the Chinese slice of the import bill. With near-full pass-through at the border and partial pass-through to retail, and given imports are about 15 percent of GDP, the direct CPI effect is more negligible—on the order of a few tenths of a percentage point spread across categories—but the capital-goods channel matters more: higher prices for machinery and components erode multi-factor productivity over time. This is precisely the margin on which education and R&D policy can dominate tariff policy.

Now adjust for substitution. The New York Fed shows that some “lost” China imports reappear via third countries; the WTO notes that tit-for-tat tariffs and uncertainty can turn global trade growth negative. That means some apparent “wins” are accounting reallocations, while the macro drag is real. A policy premised on squeezing deficits by rerouting supply chains will deliver, at best, noisier statistics and, at worst, weaker investment. A policy premised on compressing the cost of learning—via apprenticeships, sectoral training, and translational research—compounds into export capacity. That is the substitution we should want.

What a Learning-First Trade Policy Looks Like

Start where returns are measurable: the CHIPS and Science Act’s fabrication grants and loans are tying public money to concrete plants, processes, and—crucially—workforce pipelines. In 2024, the Commerce Department announced preliminary agreements of up to $8.5 billion for Intel, $6.6 billion for TSMC Arizona, and $6.4 billion for Samsung’s Taylor, Texas complex, with final awards subsequently issued in several cases and loan authorities alongside. Each package embeds workforce training and supplier development, the pieces that turn concrete into clusters. We should treat this not as a one-off industrial act, but as a template: condition public support on co-investment in regional talent ecosystems and on open, competitive vendor bases that spread learning to smaller firms.

Scale the human capital side with tools we already have. Registered apprenticeships, community-college consortia, and employer-validated micro-credentials can be expanded and fast-cycled around the needs of semiconductors, power electronics, precision machining, and advanced materials. The adult-skills evidence argues for doing this at pace: numeracy and problem-solving deficits are widespread among working-age adults, not just students, which means we need “earn-and-learn” models that lift skills without pulling people out of the labor force. If we must subsidize something, subsidize mastery: the conversion of imported equipment into domestic capability. That is the most durable way to move the trade balance—from the numerator of imports to the denominator of export sophistication.

Aim Higher on Product Strategy: Compete Where Price Is Not the Margin

A frequent claim in tariff debates is that allies “block” market access for U.S. consumer durables, especially cars. But the data point to a product-market fit problem more than tariffs: Japan’s market is dominated by small segments with dense service networks and localized options, while U.S. brands chase different segments and platforms. Recent trade guides and industry analyses emphasize that non-tariff barriers exist, but preferences, size constraints, and after-sales infrastructure explain many outcomes. In other words, even if we “won” a tariff concession on paper, we would not sell Crown Victorias into Tokyo cul-de-sacs. The relevant lever is differentiated product design, not punitive duties that boomerang on domestic parts suppliers.

The lesson generalizes. Where the United States invests at the frontier—chips, design tools, AI-enabled manufacturing, specialty chemicals, aerospace—it tends to export pricing power rather than chase volume. The way to “knock out” a rival is not by taxing your inputs; it is by out-learning them in technologies with steep knowledge curves and high switching costs. This is precisely what targeted R&D, procurement standards that reward performance (not lowest bid), and global standards leadership can deliver. Tariffs can occasionally buy time in a thinly traded, security-critical niche; they cannot buy technological lead time. The latter is earned in classrooms, labs, and factories.

Anticipating the Critiques—and Answering Them

What about national security? Export controls on truly sensitive nodes—leading-edge logic and memory, EDA tools, advanced lithography—are legitimate and often necessary. But controls are scalpels, not mallets: they work when coordinated with allies, calibrated to chokepoints, and paired with domestic capacity-building so that denial does not become self-denial. The IMF’s recent work stresses that broad fragmentation is costly; the goal should be narrow, enforceable guardrails where security is most at risk, alongside vigorous competition elsewhere. In education terms: defend the exam room; don’t shutter the school.

What about “tariff revenue” as a policy win? Revenues are real, but they are taxes by another name. Studies of the 2018–2019 duties found near-complete pass-through to U.S. importers and consumers; a tax that mostly lands on your firms is not a growth strategy. If we want fiscal space, it is better raised transparently and spent on investments with high multipliers—adult numeracy programs tied to industrial demand, regional apprenticeship hubs, matched employer training grants—than collected opaquely at the border and dissipated in higher prices. Deficits are macro outcomes; advantages are micro decisions. Policy should be built for the latter.

The Only Durable Surplus Is a Surplus of Capability

If one number frames the path forward, it is not the monthly deficit but the share of adults who can reason with ratios, debug a process, or qualify a tool on the first pass. Tariffs can temporarily redistribute where we buy; they cannot fabricate the skills or systems that make the world buy from us. The 2025 data remind us that import shares can be reshuffled while costs rise, and that fragmentation can slow the very trade we want to lead. An innovation-first, education-centered trade strategy starts from the ground up: compress the price of learning, flood the system with opportunities to master complex tasks, and target public money where it builds clusters that export quality. Do that, and deficits will matter less because the products will matter more. Our call to action is demanding and straightforward: retire the politics of bilateral tallies, and fund the institutions that compound know-how—labs, classrooms, apprenticeships, supplier networks. Advantages are built, not declared; walls only get in their way.

The original article was authored by Vijay Joshi and David Vines. The English version of the article, titled "How Donald Trump should have tackled the US trade deficit," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Amiti, M., Redding, S., & Weinstein, D. (2019/2020). The Impact of the 2018 Tariffs on Prices and Welfare; Who’s Paying for the U.S. Tariffs? A Longer-Term Perspective. American Economic Association; NBER Working Paper 26610.

Council on Foreign Relations (Setser, B. W.). (2024). Why U.S. Imports From Mexico Surpassed Those From China.

Intel Newsroom. (2024, Mar. 20). Intel and Biden Admin Announce up to $8.5 Billion in Direct Funding Under the CHIPS Act.

International Monetary Fund. (2024–2025). World Economic Outlook (April 2024; updates 2024–2025); Gopinath (2024), Geopolitics and Its Impact on Global Trade and the Dollar.

Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association (JAMA). (2024). Motor Industry of Japan 2024.

New York Fed (Liberty Street Economics). (2025). U.S. Imports from China Have Fallen by Less Than U.S. Data Indicate.

NIST / U.S. Department of Commerce. (2024, Apr. 15 & Nov. 15; Nov. 26). Preliminary Terms and Final Awards under the CHIPS Incentives Program (Samsung; TSMC; Intel).

OECD / NCES. (2024). PIAAC 2023: United States Findings and Highlights.

Peterson-adjacent synthesis (Vox). (2025). The Misunderstanding Breaking the Global Economy (Trump deficit fixation and bilateral tariffs).

Richmond Fed. (2025). Tariffs: Estimating the Economic Impact of the 2025 Tariffs; Tariff Update; Speaking of the Economy podcast.

Samsung Semiconductor Newsroom. (2024, Apr. 15). Samsung Electronics to Receive up to $6.4 Billion in Direct Funding.

TSMC Press Release. (2024, Apr. 8). TSMC Arizona and U.S. Department of Commerce Announce up to $6.6 Billion in Proposed CHIPS Act Funding.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (with Census). (2025, Aug. 5). U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services: June 2025.

U.S. International Trade Commission. (2025, Jul. 1). USMCA Automotive Rules of Origin: Economic Impact and Operation, 2025 Report (release notice); Riker (2024) Imports and the Location of Vehicle Production.

USTR. (2024, Mar. 29). 2024 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers; press summary.

World Trade Organization. (2025, Apr. 14). Global Trade Outlook 2025.

Comment