From One Mill to Many: Rewiring Australia's Minerals Strategy with India and Southeast Asia

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

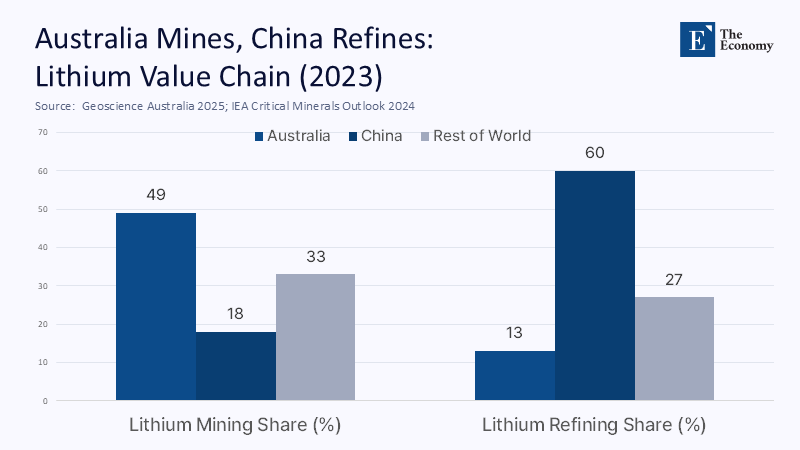

One statistic highlights Australia's situation: nearly half of the world's lithium is mined in Australia, while more than 60% of its processing occurs in China. Coupled with the fact that about a third of Australia's total export value is still directed to China—mainly due to iron ore from Western Australia, where around 80% of the export value goes to Chinese steel mills—the inherent risk becomes apparent. When the same nation purchases the ore and manages the processing that transforms minerals into battery-grade chemicals and magnet oxides, any geopolitical tension or domestic economic slowdown quickly turns into an issue for us. China's recent restrictions on crucial inputs like gallium, germanium, and graphite highlight how bottlenecks in processing can be utilized as political tools. As China grapples with a property market downturn and shifts toward a focus on self-sufficiency in raw materials, Australia must also adapt—steering its efforts toward a downstream market with India and Southeast Asia to mitigate reliance on a single country while supporting the energy transition.

Reframing the Risk: Processor Dependence, Not Just Buyer Concentration

Canberra has long viewed the "China question" primarily as a risk of over-reliance on a single market. However, the greater vulnerability lies in processor concentration, particularly in key stages of the supply chain like lithium and nickel conversion, rare-earth separation, and metal-to-magnet processes. These chokepoints can significantly affect the entire supply chain, underscoring the need for diversification. With Australia's alliances with the US and UK, there's a stronger incentive to rethink where value is added, especially given the impact of Chinese export controls.

Amid China's property downturn leading to lower steel demand and iron ore prices, Australia cannot rely on past demand or assure future access to Chinese processing. The response should be to 'derisk' by investing in processing capabilities outside of China. This involves forming new partnerships and financing with entities in India and Southeast Asia that can help reduce risks and enhance manufacturing capabilities.

The Chokepoints We Must Move: From Refining to Magnets

The International Energy Agency's 2024 critical minerals outlook laid out the concentration problem in plain numbers: China dominates refining across key battery and magnet inputs—majority shares in lithium and nickel refining, around 70% in cobalt refining, and close to 90% in rare-earth separation. Australia, by contrast, leads in mining—49% of global lithium output in 2023—but still ships most of the value uplift to offshore processors. Western Australia accounted for all of Australia's lithium production and nearly half of the world's ten-year supply increase, yet conversion capacity onshore is embryonic and economically exposed to price cycles. The result is a robustness paradox: record mine output paired with mid-stream fragility.

Iron ore tells a parallel story. WA's iron ore exports remain overwhelmingly China-bound, while China is investing to curb import reliance, expand scrap use, and bring on Simandou's high-grade tons. Even if near-term imports stay high, the strategic intent is unmistakable, and price risk follows. In rare earths, Australia's Iluka refinery financing shows the government can unlock midstream, but scale and market pull are still needed. The lesson across commodities is consistent: to derisk, Australia must both (a) build conversion at home where economics allow and (b) co-locate mid-stream where end-market demand is scaling—most credibly in India and select Southeast Asian hubs.

India as the Downstream Anchor

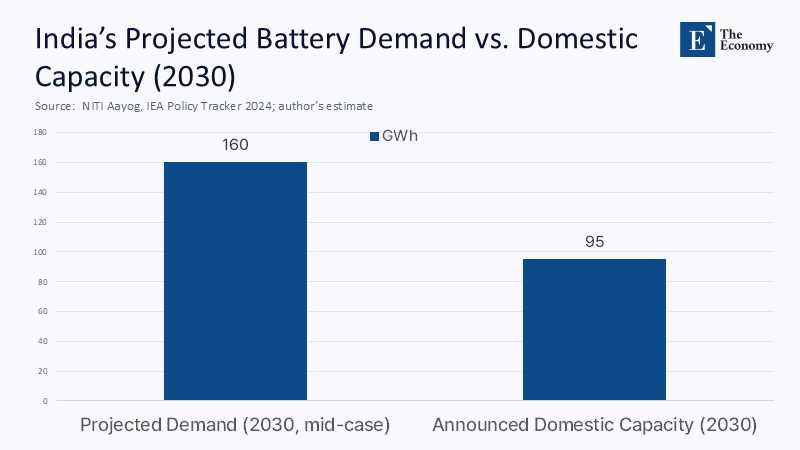

India brings three decisive assets: scale, speed, and a trade architecture already aligned with Australia. On scale, India's economy is set to remain the world's fastest-growing large market, with the IMF and New Delhi both pointing to growth above 6% through the mid-2020s. On energy and mobility, India targets 500 GW of non-fossil capacity by 2030. It has crossed the 220 GW renewable mark, while EV sales are accelerating from a low base—over two million units in FY2024-25 across segments, dominated by two- and three-wheelers. This trajectory implies a steep ramp in cell demand: policy studies place 2030 battery needs between roughly 145–260 GWh, far outstripping today's announced domestic capacity under production-linked incentives. That gap is exactly where Australian offtake and processing partnerships plug in.

The Australia–India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement, effective since late 2022, has cut tariffs on ores and critical minerals. Meanwhile, the KABIL–Critical Minerals Office is identifying lithium and cobalt projects for joint investment. India's push for large-scale manufacturing aligns with Australia's need for diverse markets. This includes establishing 10- to 15-year 'offtake contracts,' which are long-term agreements ensuring producers and buyers secure products at fixed prices. These contracts reduce risks for Indian conversion plants in exchange for equity and technical support. Mid-stream plants in Gujarat, Odisha, or Tamil Nadu can process Australian spodumene and nickel concentrates into hydroxide and sulfate, bolstered by India's manufacturing and a rules-based FTA.

A Back-of-the-Envelope That Changes the Conversation

Consider a conservative allocation of India's 2030 battery demand at 160 GWh. Using a mid-case 0.8 kg of lithium carbonate equivalent per kWh across mixed chemistries implies ~128,000 tonnes LCE annually. Australia's 2023 output equates—after converting contained lithium to LCE—to several hundred thousand tonnes equivalent, suggesting that even a one-third Indian share could be met with current or modestly expanded Australian supply routed through Indian refineries. Pair that with nickel sulfate demand for high-nickel chemistries and cobalt for specialty applications, and the economics of co-located mid-stream get compelling, especially with tax and tariff relief under ECTA. The point isn't to shift all volumes; it's to create a second gravitational center for processing that disciplines risk and improves bargaining power.

This is not conjecture. India's battery and EV targets, worldsteel's robust steel-use outlook for India, and ongoing grid investment mean structural, not cyclical, demand. And while India's EV passenger-car penetration remains low today, the two- and three-wheeler base scales chemistry demand quickly. Suppose offtakes tie the Australian feedstock to the Indian conversion with predictable floor-price mechanics and green-energy sourcing. In that case, capex can be financed competitively by tapping Australian superannuation pools alongside Indian public-sector banks. The upside is strategic as much as commercial: a diversified, allied midstream that third-country policy shocks cannot turn off.

Southeast Asia as the Complementary Corridor

Indonesia has become the world's key nickel hub, with increased mining and processing following the ore-export ban. While its nickel production is currently carbon-intensive, it leads in global NPI, matte, and emerging sulfate capacity. The Philippines, the second-largest producer, is seeking non-Chinese investment to enhance its refining capacity for a greener value chain. Vietnam, despite revised reserve estimates, remains a strong player for magnets and components, with Korean manufacturers expanding their presence there to reduce dependence on China. This landscape offers opportunities for Australian partnerships in upstream security, mid-stream battery and nickel chemistry, and downstream markets across Asia.

Australia's rare-earth path shows how to make this real. Canberra's expanded loan support for Iluka's refinery in Western Australia demonstrates that public capital can unlock market-shaping projects. Replicating the model across the region—co-financing Vietnamese magnet plants that offtake mixed rare-earth carbonate from Australian mines, for example—would create a non-Chinese magnet supply for EVs and wind. Meanwhile, collaborative standards on emissions, labor, and transparency can differentiate an Indo-Pacific corridor from coal-heavy alternatives, lifting social license. None of this precludes Chinese trade where it makes sense; it simply builds credible outside options.

The Playbook: Finance, Offtake, Standards, Skills

The financing tools are already on the table. A $4 billion facility backs Australia's Critical Minerals Strategy and, crucially, a production tax incentive worth 10% of eligible processing and refining costs from 2027 to 2040, now passed into law alongside a hydrogen credit. That is a powerful anchor for bankability if paired with long-term offtakes into Indian and Southeast Asian plants. Add in export-credit agencies on both sides and the Minerals Security Partnership, where applicable, and the capital stack gets dense enough to move from press release to project execution.

Offtakes are the hinge. Contracts that guarantee volume with price floors linked to cost indices give investors predictable cash flow; in return, producers gain market diversification and influence over ESG and traceability. Standards matter: if Australia wants to sell premium "clean" inputs, it should require renewable power for conversion, robust water management, and Indigenous engagement baked into every term sheet. Skills mobility is the final mile. An Australia–India–SEA skills compact—short-term visas, joint training, and placements around chemical operations—would accelerate commissioning and diffuse operational excellence without draining Australian capability. AUKUS-adjacent dialogues on critical minerals can widen the aperture to allied co-investment without turning the supply chain into a geopolitical litmus test.

Answering the Objections

"China will still be cheaper, so the shift will never reach scale." Sometimes, yes—but not always. Costs are changing. New Australian tax credits narrow the delta for onshore conversion; Indian states are bidding aggressively for battery and chemical plants; and, importantly, geopolitical risk is now a hard cost that investors can price into discount rates. Even where Chinese conversion remains cheaper, the premium for a diversified, sanction-safe, export-control-proof supply is often worth paying—especially for automakers and grid developers bound by Western procurement rules and subsidy conditions. This isn't about replacing China; it's about building credible alternatives so that one plant shutdown or export permit doesn't stall an EV or transmission program halfway around the world.

"India's bureaucracy and infrastructure will slow everything down." It will slow some things, not all. The past two years have seen an acceleration in non-fossil additions, a sharp expansion in crude-steel output, and a steady build-out of EV and storage policies. ECTA removes tariff friction, KABIL provides a funnel for project diligence, and Indian corporates are forming JVs from green hydrogen to storage. Yes, land and permitting still bite, so design around them. Start with brownfield port and industrial parks; deploy modular conversion trains that can ramp; and fuse offtake and equity to keep timelines disciplined. Private-law protections, including international arbitration in offtakes, can tighten execution even where local administrative risk persists.

What Success Looks Like by 2030

By 2030, a resilient map would show Australian spodumene split across three destinations: a share refined in Western Australia under the 10% production credit; a significant tranche refined in India for hydroxide and precursor cathode materials; and a third routed to Indonesia or the Philippines as nickel-bearing inputs for sulfate and mixed hydroxide. Rare-earth carbonate from Australian mines would feed both Iluka's WA refinery and a Vietnamese magnet corridor co-financed with allies. At least a handful of these flows would sit under offtakes with floor-price bands and ESG performance ratchets, audited for renewable power and community impacts. The market optionality that results would reduce Australia's exposure to any single policy jolt—whether a tariff headline, a graphite permit squeeze, or a property-led metals demand dip in China.

The net effect inside Australia would be healthier margins and steadier investment through cycles. When iron ore faces a price lull and Simandou ramps, conversion earnings help smooth the curve. When lithium prices sag, long-dated offtakes and credits cushion cash flow and keep projects alive until the next demand leg from India's storage and mobility build-out. When rare-earth prices swing, magnet offtakes tied to non-Chinese auto and wind pipelines provide ballast. Option value is a strategy, not an afterthought.

From Lifeline to Lattice

Australia's China story has long been told as a lifeline: our ore in their mills, our spodumene in their refineries, our prosperity in their boom. That story is ending—not in a rupture, but in a redesign. China's property slump and export-control playbook have exposed the risks of concentrating both demand and processing in the same place. At the same time, India's growth, decarbonisation drive, and manufacturing ambitions, plus Southeast Asia's nickel and magnet potential, offer a practical route to spread risk while moving up the value chain. The task before us is execution, not invention: close offtakes, deploy the new production tax credit, co-finance mid-stream in India and ASEAN, and insist on standards that match our brand. If we do, the next decade's map will show not a single lifeline to one buyer, but a lattice of partners spanning one small ocean—resilient, rules-based, and aligned with the energy transition we all need.

The original article was authored by Trishala Sancheti, a Research Fellow at the India Foundation. The English version, titled "An India–Australia mineral partnership is critical for resilience," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

APH Parliamentary Library (2025). Critical minerals in Australia. 15 July 2025.

ATO (2025). Critical Minerals Production Tax Incentive. 20 Feb 2025.

Austrade (2023). AI-ECTA: Critical Minerals. 19 Oct 2023.

CSEP (2025). India-Australia Cooperation: Critical Minerals for Economic Security. 17 Apr 2025.

DFAT (2022–25). Australia-India ECTA (in force) & outcomes.

Export Finance Australia (2024). Record imports from Australia; China 32% of exports. July 2024.

Geoscience Australia (2025). Critical minerals at GA; Australia produced 49% of global lithium in 2023.

Government of India, MNRE/PIB (2025). India's RE capacity at 220 GW; trajectory to 500 GW non-fossil by 2030. 10 Apr 2025.

IEA (2024). Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024. (processing concentration, Indonesia nickel).

Iluka financing — Financial Times (2024). Australia boosts loan for rare-earths refinery.

Indian Ministry of Steel (2025). Overview of Steel Sector; capacity and production. May 2025.

India–Australia KABIL–CMO MoU details — IEA Policy Tracker; MEA Joint Statement (2024).

ORF America (2025). China's critical mineral export controls (2023–25). 22 Apr 2025.

Reuters (2025). China property prices/investment still falling; iron ore/Simandou outlook; MOFCOM lifts wine tariffs (2024).

RUSI (2024). Australia's critical minerals strategy amid US–China rivalry. 22 Apr 2024.

WA Government (2024, 2025). Battery & Critical Minerals Profiles; WA iron ore profile.

Worldsteel (2024, 2025). Short Range Outlook; monthly crude steel data (India).

Comment