From Convenor to Counterweight: Building a Southeast Asian Security Council for the Tariff Age

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

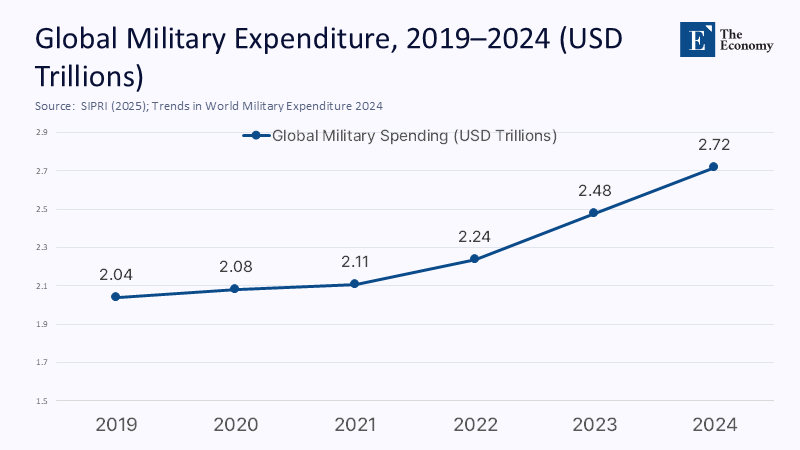

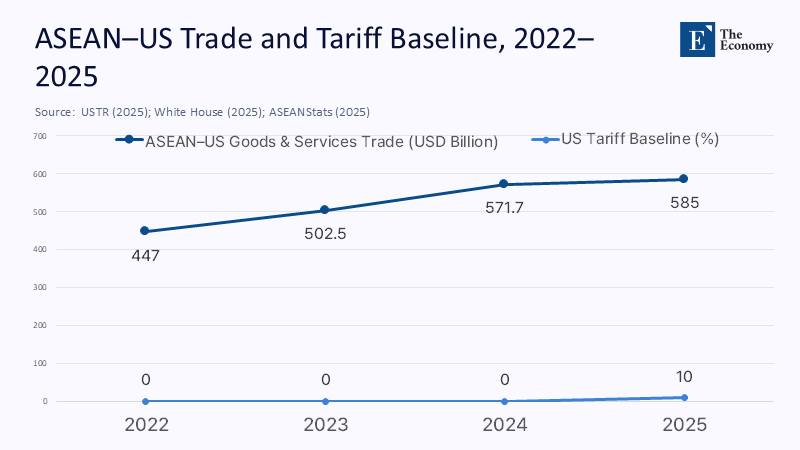

In 2024, global military expenditures surged by 9.4%, marking the most significant increase in at least a generation, totaling a historic $2.718 trillion. Nevertheless, Southeast Asia, a crucial maritime hub that supports one of the most heavily trafficked sea routes in the world, still lacks a unified security framework to effectively address rising tensions in the South China Sea or manage cross-border civil conflicts. During the same timeframe, the United States introduced a 10% baseline tariff on all imports starting in April 2025, subsequently negotiating specific rates with each country, which compelled Southeast Asian governments to engage in bilateral efforts to protect their export sectors. ASEAN continues to boast a strong economy, with over $3.8 trillion in goods trade in 2024, making the region the fourth-largest trading partner of the United States. However, in terms of security and economic strategy, it functions more as a forum than a significant counterbalance. For Southeast Asia to achieve genuine centrality, it requires a compact that connects maritime defense collaboration with external negotiation capabilities, formalized through the establishment of a standing Southeast Asian Security Council.

Reframing the Problem: From “Consensus First” to “Security-for-Trade”

The prevailing view is that ASEAN's centrality is weakened by great-power competition, such as China's maritime assertiveness and US-Japan supply chain realignments. While this perspective is valid, it overlooks a deeper issue: the lack of a robust collective-security mechanism within ASEAN. This leads member states to rely on bilateral ties, particularly with the US, instead of leveraging ASEAN itself in times of crisis, like tensions around Second Thomas Shoal. For ASEAN to regain centrality, it must view collective security as a practical tool linked to market access and tariff relief, effectively trading coordinated maritime efforts for enhanced bargaining power.

This urgency is amplified as security risks escalate, particularly with aggressive Chinese tactics near Philippine positions and rising US tariff policies creating a new "price of entry" to its market. If maritime and tariff pressures coincide, states negotiating individually risk being disadvantaged both at sea and in trade. Thus, a coordinated defense and trade strategy within ASEAN is crucial to translate its collective size into bargaining strength.

The Maritime Deficit: Incidents Rise, Rules Stagnate

The South China Sea has become a slow-motion test of regional crisis management. Documented water-cannoning and collisions during 2024 resupply missions to Second Thomas Shoal, plus fresh incidents publicized in August 2025, show a pattern of calibrated coercion that imposes costs without triggering formal war. These tactics thrive where coordination is thin. Although ASEAN has nurtured valuable mechanisms—the ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM), ADMM-Plus exercises, and the ASEAN Maritime Outlook—the bloc still lacks a mandated body to authorize time-bound joint maritime measures in the event of a surge in incidents. That gap increases the premium on external patrons and weakens ASEAN’s claim to set the rules of the game in its waters.

Talks on a binding Code of Conduct with China have stalled. Expert surveys in mid-2025 judge completion unlikely under current terms, while policy studies argue the process is stuck on legal scope and enforcement. In parallel, world military spending hits records, and several Southeast Asian budgets creep up from low bases, yet capacity building remains national, not pooled. Without a venue that can fuse maritime domain awareness, joint patrol approvals, and crisis communication across capitals, Southeast Asia buys more hardware but not more centrality. The implication is not to abandon ASEAN’s “outlook” documents but to upgrade them with an operational arm that acts when paper norms are evaluated at sea.

The Tariff Shock: External Leverage Without Internal Coherence

Trade is where Southeast Asia’s weight is undeniable. In 2024, ASEAN goods trade reached $3.84 trillion, and US–ASEAN trade hit about $572 billion in 2024 as the region stood as America’s fourth-largest partner. Yet tariff politics in Washington now sorts partners into bespoke rate tiers. After the April 2025 10% baseline came into force, countries rushed to negotiate down from higher perspective rates; Thailand publicly touted a 19% deal, while others navigated bespoke terms. This dynamic rewards speed and bilateral influence. It penalizes slower, smaller, or politically constrained negotiators—and it creates incentives for divide-and-deal approaches that splinter ASEAN’s collective voice.

A collective response would not mean a customs union. It would link maritime responsibilities to trade benefits: states that contribute patrol assets, boarding teams, or surveillance to common missions earn proportional backing—market access advocacy, coordinated quota management, and synchronized standards recognition—in joint negotiations with major partners such as the United States, Japan, and the EU. In short, security-for-trade: a compact that converts public goods provision at sea into bargaining chips at the table. Done right, it would also reduce the temptation for extra-regional powers to treat Southeast Asia as a menu of bilateral deals rather than a constituency with minimal thresholds and shared red lines.

Blueprint for a Southeast Asian Security Council (SEASC)

Design should start small, act fast, and remain open. The Southeast Asian Security Council (SEASC) would be a ministerial body under ASEAN, utilizing a qualified-consensus rule: action proceeds with a supermajority of seven members agreeing and no more than two objecting. Its core functions would include authorizing limited joint maritime operations, coordinating humanitarian-and-disaster-relief (HADR) deployments, and triggering diplomatic démarches against gray-zone coercion.

To integrate security with economics, the SEASC would partner with a Trade Response Cell of senior economic officials to draft unified tariff negotiation requests and track external rate changes. This would allow members to exchange concessions, such as maritime deployments for market access. A one-year pilot focusing on maritime incidents in the Spratly area and tariff flows to the U.S. would pave the way for broader engagement as trust develops.

Internal Conflicts, External Credibility

Myanmar’s civil war remains a significant fracture line, and four years after the 2021 coup, ASEAN's Five-Point Consensus has seen limited progress. Fighting has intensified, with border towns like Myawaddy changing hands and many refugees fleeing to Thailand and Bangladesh. While ASEAN has attempted special meetings and “parallel diplomacy,” front-line states are left to manage cross-border issues alone.

A Southeast Asia Security Cooperation (SEASC) could create a platform for neighbors to share intelligence, coordinate border stabilization, and deploy humanitarian assistance without turning every action into a political statement. This shift towards operational cooperation could save lives and demonstrate ASEAN's capability to act amidst internal debates.

Moreover, recent intra-ASEAN tensions, such as episodes along the Thai-Cambodian border, highlight the need for trusted mechanisms to minimize external mediation. The SEASC design should include recusal protocols for disputes, third-party fact-finding from retired officials, and automatic humanitarian assistance standby when civilian infrastructure is affected. This approach aims to limit external influence while maintaining partnerships with the U.S. and Japan, ensuring credibility abroad begins with predictability at home.

Why This Is not the EU—and Why That is an Advantage

Critics will argue that a security council, even a modest one, cuts against ASEAN’s non-interference norm and risks provoking China. The answer is design. The SEASC would be bound by purpose (maritime safety, HADR, crisis signaling), limited by time (pre-set mandates), and flexible in participation (opt-outs allowed). That is not an EU-style supranational leap; it is a next step in functional integration, the same strategy ASEAN used to build out economic cooperation while preserving sovereignty. The risk of provocation is lower when red lines are defined, thresholds are published, and actions are collective and proportionate. Ambiguity invites testing; clarity deters it.

Others will say the region can keep muddling through with ADMM-Plus exercises, coast-guard dialogues, and informal crisis calls. Those are necessary but insufficient. Exercises without an authorizing venue risk becoming rehearsals for actions that never come. Dialogues without a trade counterpart leave tariff politics to fragment the very coalition security cooperation seeks to build. And unilateral budget hikes—Philippine outlays rose again in 2024 from a low base—cannot buy the collective predictability that investors and partners require. A minimalist SEASC creates exactly one thing ASEAN does not yet possess: a switch that can be flipped when the sea gets rough and the customs line hardens.

Implementation: Metrics, Money, and a One-Year Pilot

The first year should evaluate three deliverables:

1. A live maritime domain awareness (MDA) feed integrating national coastal radars and satellite AIS for Palawan and the Spratlys, with privacy safeguards.

2. A rapid HADR-plus-medical rotation capable of moving within 72 hours, pre-cleared for land and sea entry.

3. A tariff response playbook detailing sector-specific asks for US negotiations and legally available reciprocity for partners penalizing ASEAN’s maritime public goods provision. Each deliverable will have a public scorecard measuring response time, incident reduction, and negotiated rates to quickly establish credibility.

Funding should be modest but consistent, based on a GDP-proportional dues formula and contributions from partners like Japan, Australia, and the US, using transparent trust funds. The investment pays off as shipping premiums decrease with better risk management, and exporters benefit from coherent tariff requests. Ultimately, the council’s history of deterrence and relief will demonstrate that Southeast Asia embodies "centrality."

Anticipating the Pushback—and Rebutting It with Evidence

A common critique is that any hint of “collective security” will split the bloc between mainland and maritime camps. But the split already exists; what is missing is a procedural bridge that lets coalitions of the willing act without dragging abstainers. Qualified-consensus with opt-outs is that bridge. Its legitimacy rests on published thresholds and public reporting, not unanimity for its own sake. This is how ASEAN can maintain inclusivity while avoiding paralysis when lives and ships are at risk. It is also how the bloc can keep extra-regional partners close without outsourcing its agency to them.

Another pushback is that tying trade advocacy to security contributions amounts to coercion. Yet tariff politics is already coercive when wielded bilaterally against fragmented responders. A security-for-trade compact reverses the asymmetrical: it rewards public goods provision with collective bargaining power. The evidence from 2025 is clear: countries that moved quickly bilaterally cut their rates; others lagged. That pattern is a vulnerability masquerading as flexibility. Turning it into a rule-bound swap makes the process fairer, more transparent, and more defensible to domestic constituencies that ask why their taxes fund patrols while competitors free-ride—and still undercut them at the border.

Centrality by Design, Not by Rhetoric

The headline numbers tell us why the old approach will not hold: record global military spending, accelerating gray-zone pressure at sea, and a tariff framework that sorts partners into winners and losers at the speed of a press release. Southeast Asia cannot find its way through this trifecta. It must institutionalize responsiveness in security and pool leverage in trade. A Southeast Asian Security Council, narrowly drawn and pilot-tested, is the mechanism that converts ASEAN’s economic heft into strategic agency. By authorizing limited, measurable maritime actions, pairing them with a disciplined tariff response, and insulating both from unanimity deadlock, the region can make “centrality” visible where it counts: on radar screens, in response times, and at the negotiating table. The alternative is familiar—bilateral fixes, reactive diplomacy, and a steady drift from convenor to bystander. It is time for Southeast Asia to become a counterweight to its design.

The original article was authored by Tin Shine Aung, the Consulting Director at the Shwetaungthagathu Reform Initiative Centre (SRIc). The English version, titled "ASEAN’s centrality depends on a shift to collective security," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Asia Society Policy Institute. (2024). On U.S.–ASEAN relations & trade (ASEAN as the 4th-largest US trading partner; 2023 figures).

ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM). (2024). Vientiane Joint Declaration of the ADMM: Together for Peace, Security and Resilience.

ASEAN Secretariat. (2019). ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific.

ASEANStats. (2025). ASEAN Key Indicators: Trade in Goods (US$3,844.3 billion in 2024), population 677.6 million (2023).

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), AMTI. (2024). Shifting tactics at Second Thomas Shoal.

Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). (2024). Timeline: China’s maritime disputes (Second Thomas Shoal incidents, 2024).

East Asia Forum. (2025). ASEAN’s centrality depends on a shift to collective security.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2025). World Economic Outlook Datamapper (selected indicators; ASEAN-5 share, global growth).

ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute. (2025). The Elusive Code: Why ASEAN Needs a New Playbook for the South China Sea.

PacNet / Pacific Forum. (2025). Beyond the unfinished code: Rethinking ASEAN’s maritime centrality without a CoC.

Reuters. (2024). Clashes and refugee flows at Myanmar–Thailand border (April 10, 12, and 20).

Reuters. (2025). ASEAN schedules Myanmar-focused meetings (May 21); ASEAN says Myanmar election not a priority (July 11).

SIPRI. (2025). Trends in world military expenditure, 2024 (fact sheet and press release).

US Department of Agriculture, ERS. (2025). Southeast Asia: Growing potential for US agriculture (US exports to SEA in 2023).

US Trade Representative (USTR). (2025). ASEAN—trade summary (US goods & services trade with ASEAN totaled $571.7b in 2024).

White House. (2025). Fact sheet: National emergency to impose 10% baseline tariff and reciprocal rates (effective April 2025).

Comment