Make Exits Cheap, Make Entry Bold: India’s Hidden Tax on Manufacturing Ambition

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

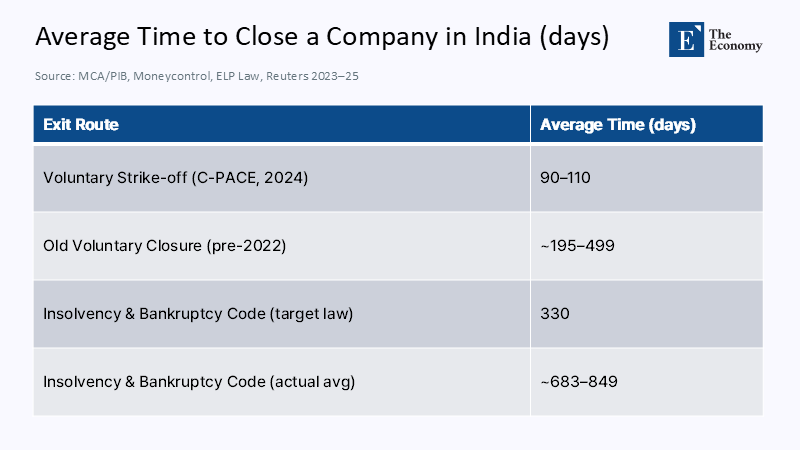

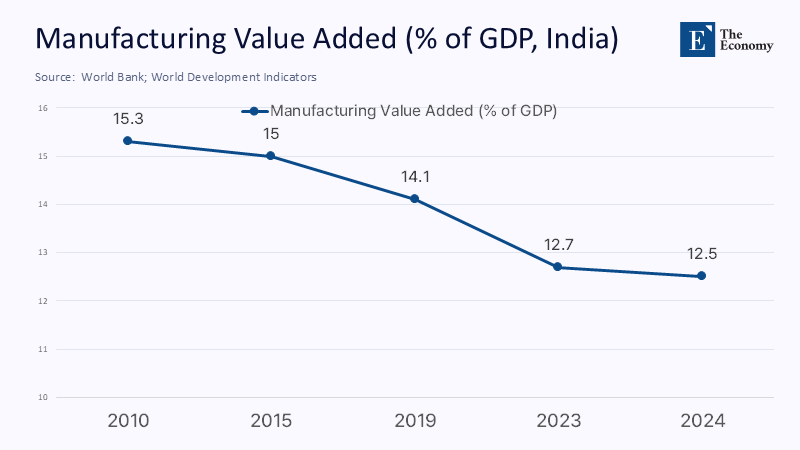

The statistic that should alert India's industrial policymakers is not a tariff or an overall growth percentage. It is the duration it takes for a failing factory to shut down—and how that lag deters the investment that could potentially take its place. In 2024, the process for voluntary company strike-offs in India was completed in approximately 90–110 days, thanks to the newly implemented C-PACE system (a significant reduction from around 195–499 days just two years prior). However, an exit through the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) typically exceeds the 330-day statutory limit—credible estimates range between about 683 days and 849 days, with high-profile reversals introducing legal unpredictability. Meanwhile, the contribution of manufacturing to GDP remained around 12.5% in 2024, its lowest level in decades by various metrics. When these elements are considered together, they convey a clear message: slow and uncertain exits serve as an entry tax. They immobilize assets, deter risk-taking, and favor capital-heavy incumbents that can afford to endure the wait. If India aims to increase the number of new plants, it must first assist the weaker ones in closing—efficiently, swiftly, and reliably. The critical nature of this problem cannot be emphasized enough.

Reframing the Problem: Exit Costs as the Invisible Entry Tax

The conventional framing blames India’s disappointing performance in labor-intensive manufacturing on expensive machinery, global demand shifts, or a shortage of “skills.” Those all matter. But the binding constraint is institutional: how costly and uncertain it is to shut a plant, retrench workers lawfully, and resolve debts. Exit costs operate like an insurance premium that every would-be entrant must mentally prepay. Even firms that never fail price in the risk that, if they do, they will be trapped in procedural limbo—paying counsel, watching machinery depreciate, and waiting for a court date that moves. This is not a theoretical quibble. Recent empirical work shows that high exit frictions deter entry, prolong inefficient survival, and depress aggregate productivity; Indian states with more challenging exit environments show less churn and more misallocation. When finality is uncertain—as illustrated by the Supreme Court’s 2025 reversal of a landmark steel resolution years after approval—investors widen required returns or walk away. Exit frictions are, in effect, a tax on experimentation; reducing them lowers the price of trying new things.

A second reframing follows: exit policy is labor policy. In systems where exit is clogged, firms avoid permanent hires or push activity into the informal sector. The result is a dual labor market that protects a few insiders while offering insecurity for many. India’s central Industrial Relations Code (2020) moves toward clarity, but implementation has lagged at the state level; unpredictability persists around permissions for retrenchment and closure, and the real-world cost of compliance. Until exit is standardised, time-bound, and consistently applied across jurisdictions, firms will insure themselves by using fixed-term contracts and automation—even when the technology choice is sub-optimal for job creation. The “make labor safe by making exit impossible” model ends up making entry rarer and work more precarious for those outside formal factories. This standardization is crucial and underscores the importance of the role of legal experts in this process.

What Exit Costs Look Like in Practice

There are three layers of exit friction impacting businesses.

First, labor law thresholds under the 2020 Industrial Relations Code require government permission for layoffs or closures in establishments with 300+ workers, with looser rules for smaller firms. However, they still owe statutory retrenchment compensation and notice requirements. This complexity leads firms to avoid exceeding the threshold, resulting in higher operational costs.

Second, the insolvency process, while improved by the IBC, remains lengthy, averaging ~683 days compared to the ideal of 330 days. High-profile cases have shown risks of post-resolution reversals, making it harder to predict outcomes. This delay results in lost collateral and deteriorating company morale.

Lastly, administrative closures have improved, with the Centre for Processing Accelerated Corporate Exit (C-PACE) reducing the time to strike off solvent companies to 90–110 days. However, lingering tax claims and compliance disputes can inflate exit costs further, hindering the reallocation of assets.

The Reform Paradox: Quick Voluntary Exits, Slow Distress Exits

India now offers a tale of two exits. For solvent firms with no disputes, exit has become impressively fast; C-PACE is centralised, electronic, and measurable. For insolvent or contested cases—the ones that matter most for productivity and credit discipline—time still stretches. The issues of paradox arise because entry decisions are forward-looking. A founder imagines two futures: a good one (scale, export, hire) and a bad one (pivot fails, debt mounts). If the bad one is clean and finite, they try. If the bad one is dusty and endless, they don’t. By making the bad case less frightening, policymakers increase the number of good cases that ever happen. This growth potential should inspire optimism and drive the necessary reforms.

There is also a composition effect. Long, discretionary exits tilt the playing field toward firms that can hoard capital and legal talent, and toward capital-intensive techniques that minimize headcount risk. That shows up in macro data: India’s manufacturing share of GDP remained ~12–13% in 2023–2024 and is widely perceived as underperforming potential, despite incentives like PLI. When entry is discouraged and exit is dragged out, churn—the lifeblood of productivity—slows. The empirical literature is unambiguous: states with easier exit see higher entry and better reallocation, especially in labor-intensive sectors. The policy message is not “favor capital over labor,” but to reduce the institutional premium on capital by making workforce adjustments and bankruptcy predictable, bounded, and fair.

A Pragmatic Template from China: Simplified Deregistration and Administrative Closure

China's approach to simplifying deregistration for small, debt-free entities offers valuable insights for India. Their fast-track deregistration process involves a 20-day public notice followed by a 20-day completion window for uncontested cases. This method excludes firms with unresolved debts, aiming to differentiate between straightforward and complex exits to optimize judicial resources.

India's C-PACE initiative demonstrates the potential of centralized, digital processes to streamline timelines without sacrificing oversight. Applying this to other exit routes could enhance efficiency. For instance, tightening the design of the existing pre-packaged insolvency for MSMEs around clear timelines and majority creditor thresholds could increase usage. Additionally, tax authorities might adopt time-boxed clearances with post-facto audits for fraud. These procedural reforms would help redirect failing assets to more productive purposes without undermining oversight.

The System Upgrade India Needs: Speed, Finality, and Social Protection

A credible time clock should govern distress exits, making the 330-day statutory ideal a requirement rather than a suggestion. Specialized IBC benches with exclusive rosters, strict adjournment discipline, and digital evidence standards can significantly reduce case duration. When cases exceed deadlines, automatic fee cuts for insolvency professionals and court-monitored action plans can realign incentives. These technocratic changes could halve long-tail durations, leading to improved recoveries, reduced credit costs, and increased sector entry.

Finality is essential alongside speed. The 2025 Supreme Court reversal unsettled investors due to years-later uncertainties. Parliament and the Court should establish a clear doctrine of finality for approved resolution plans, where discovered errors lead to damages rather than rescission. Ministries should also refrain from imposing new tax demands for pre-resolution periods once a plan is approved, except in apparent fraud cases, supported by a one-stop digital clearance that binds authorities.

Lastly, implementing labor security without exit paralysis is vital. A national severance floor should be set and funded through escrowed wage insurance to ensure predictability for workers. Rapid retraining and placement support are essential. India’s initiatives, such as Karnataka’s 2025 bill for platform workers, reflect the potential for portable benefits without sacrificing flexibility. A similar structure for formal manufacturing would balance firm certainty with worker dignity.

Anticipating the Critiques—and Meeting Them with Evidence

“Lowering exit costs will enhance job security.” Prolonged, discretionary exits harm workers—who face unpaid wages—creditors, and communities with stranded assets. A predictable severance and rapid resolution provide workers with funds sooner. Reducing entry barriers leads to more plant openings over time; international evidence shows that job churn and creation are linked. In India, easier exit correlates with higher firm entry and responsiveness to economic shocks.

“India’s challenge lies in demand and technology, not exports.” Productivity doesn't require trade-offs. Exit reform serves as an affordable industrial policy, reallocating existing resources like land and talent. It supports productivity-linked incentives by allowing quick replacement of failing firms. Countries needing large-scale production must establish clear rules and efficient courts. If India streamlines its systems, capital and expertise will follow; otherwise, uncertainty will deter investment.

A System that Lets Go So It Can Grow

The fastest way to raise India’s industrial metabolism is to reduce the risk of failure. That paradox sits in the data: a solvent company can now close in about three months, but a distressed one may take two years or more to resolve—if it resolves at all. Add to that the occasional legal boomerang that undermines finality, and you have the most distortionary tax in the system: an entry tax levied through exit. The prize for reform is visible in every state and sector where churn is higher: more experimentation, faster reallocation, higher productivity, and ultimately more jobs. The playbook is not glamorous—hard clocks, clean finality, portable benefits, single-window clearances—but it is within reach and already half-built in places like C-PACE. India should finish the job. Make exits cheap and predictable, and factories will open—not because government tells them to, but because entrepreneurs finally believe they can try, fail, and try again without being trapped in amber. The road to bold entry runs through a dignified exit.

The original article was authored by Shoumitro Chatterjee, an Assistant Professor of International Economics at Johns Hopkins University, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Exit costs are entry costs: Why India needs to ease exit barriers for manufacturing firms," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bank for International Settlements. (2024, Dec 19). Strengthening the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) … (speech).

Chatterjee, S., Krishna, K., Padmakumar, K., & Zhao, Y. (2025, Aug 19). Exit costs are entry costs: Why India needs to ease exit barriers for manufacturing firms. VoxEU/CEPR.

China Briefing. (2021, Aug 24). Closing a business in China: The simplified deregistration procedure (step by step).

China Briefing. (2024, Dec 19). Closing a company in China: General vs. simplified deregistration.

Chinalawvision. (2025, Jan 20). A comprehensive guide to voluntary deregistration of a company in China.

Economic Times (Legal). (2024, Nov 19). Liquidations outpace resolutions: IBBI report shows 2.5x trend.

ELP Law. (2024). Revamping India’s insolvency framework: Challenges, trends, and improvements.

Financial Times. (2025). Businesses bemoan Indian ‘tax terrorism’ and red tape.

Government of India, Ministry of Corporate Affairs / Press Information Bureau. (2023, May 13). Centre for Processing Accelerated Corporate Exit (C-PACE) established.

Government of India, Ministry of Corporate Affairs / Press Information Bureau. (2024, Dec 29). Year-End Review 2024: CPACE reduces corporate exit processing time to 90 days.

India Briefing. (2024, Dec 30). Indian states, UTs to finalize labour code rules by March 2025.

Karnataka Legislative Assembly. (2025). Platform-Based Gig Workers (Social Security and Welfare) Bill, 2025—news coverage. Times of India.

Moneycontrol. (2024, Mar 11). Govt aims to reduce voluntary closure to 3 months; time already down to 110 days with C-PACE.

PRS Legislative Research. (2020). The Industrial Relations Code, 2020—Bill summary.

Reuters. (2025, May 8). Indian court’s reversal of $2.3bn deal casts shadow on bankruptcy law.

World Bank. (2024). Manufacturing, value added (% of GDP) — India.

World Bank. (2024). Business Ready (B-READY) 2024.

Comment