Rights, Bases, and Balance: Why Sexual Violence Around Foreign Garrisons Is a Strategic Education Problem in Northeast Asia

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

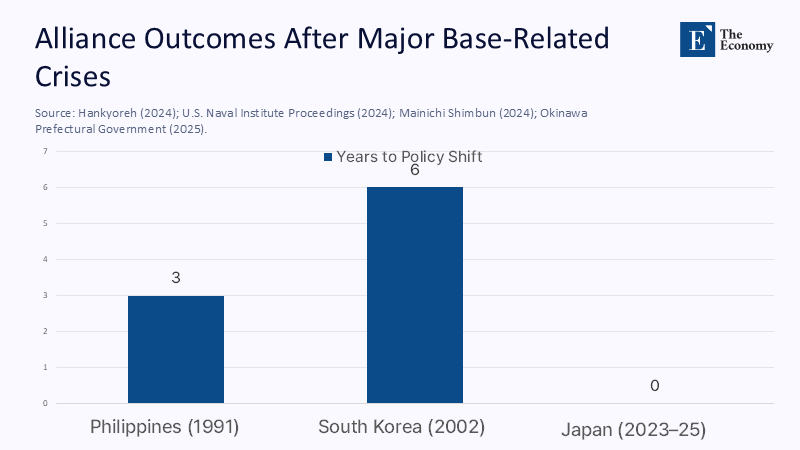

The most revealing number in Japan’s security debate is not about missiles or aircraft. It is 70.6—Okinawa’s share (by land area) of all territory used exclusively by U.S. military facilities in Japan, concentrated on islands that make up just 0.6% of the country’s landmass. In 2023 alone, 61% of the 118 criminal cases involving U.S. military personnel across Japan were recorded in this prefecture. In 2024–2025, multiple high-profile sexual assault allegations and convictions again pushed the issue to the front page and tensely back into living rooms. These are not “local disturbances”; they are structural stress tests for the alliance itself, capable of catalyzing expensive base relocations or, if mishandled, strategic vacuums. We have seen the chain of consequences elsewhere: the Philippine Senate voted U.S. bases out in 1991; within a few years, Beijing consolidated on Mischief Reef and has since escalated harassment at Second Thomas Shoal and Scarborough. Justice in courtrooms is essential. But the deeper variable is social license: whether host communities believe that security partners prevent harm and take responsibility when they fail. That is an education problem as much as a legal one.

Reframing the Risk: From Court Cases to Social License

The standard frame treats sexual assaults by foreign-based troops as legal anomalies to be punished. That misses the real risk: public consent for the alliance can erode faster than governments can manage it, especially where crimes intersect with jurisdictional gray zones under Status of Forces Agreements (SOFAs). In Japan, suspects remain under U.S. custody until indictment when Japan has jurisdiction, a provision that fuels perceptions of delay and impunity even when eventual prosecutions occur. In 2024–2025, Okinawa’s governor criticized not only alleged crimes but the flow of information, saying prefectural authorities often learned details from the press, not commanders. Each shock is amplified by the island’s disproportionate basing footprint and a history of traumatic cases, producing a cyclical narrative of grievance that outpaces official reforms.

Reframing the risk means measuring not only convictions but legitimacy: the speed and transparency of notifications, the availability of victim services outside military chains of command, and whether communities see prevention efforts as sincere and independently verified. In 2024–2025, DoD reported a second consecutive annual decrease in sexual assault reports across the force, a positive trend internally; yet, host communities evaluate credibility through local incidents and their handling, not global metrics. The strategic problem is that even rare, severe incidents can reset trust to zero. A rights-first, community-anchored approach—grounded in civilian oversight and consistent data sharing—must therefore be considered part of deterrence, not a public relations add-on.

The Philippine Warning: Outrage Can Rewire the Strategic Map

The Philippines demonstrates how a domestic tipping point can transform the regional balance. After the 1991 Senate vote ended the basing era, Washington and Manila downgraded to the Visiting Forces Agreement years later. Still, the vacuum enabled Beijing to lock in control at Mischief Reef by the mid-1990s, and to harass Philippine resupply missions more recently. Water cannons, rammings, and near-collisions have become regular hazards at Second Thomas Shoal and nearby waters, with Washington reiterating its treaty commitments even as Manila calibrates escalation control. Public opinion in the Philippines is complex—today often pro-U.S., but with persistent undercurrents of grievance around sovereignty and base-related harms that mobilize quickly after incidents. Alliances survive or falter in that crosswind.

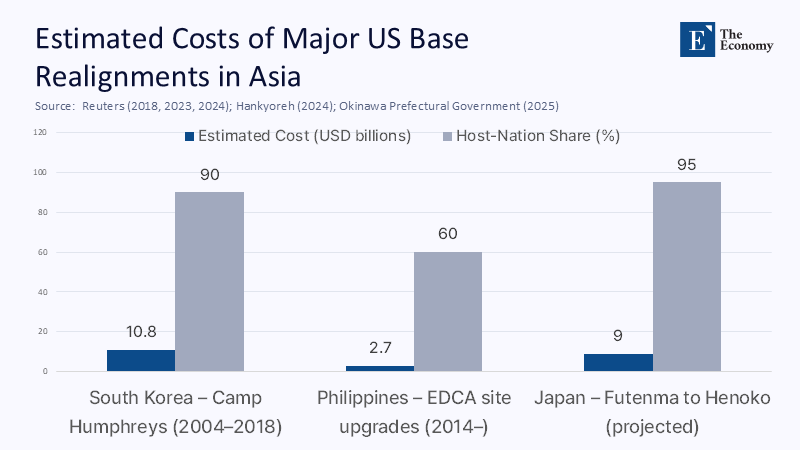

The lesson is not that closure was inevitable; it is that political coalitions formed around perceived impunity can override elite arguments about deterrence. When justice appears slow or opaque, the credibility of promises about “safety” decays. The result can be years of costly policy whiplash: eddies between base access and base denial, plus the need to re-create presence through legal workarounds such as the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement sites. That zigzag has real security costs for Manila and Washington; it also has educational costs for citizens coming of age in a media environment where each incident becomes the curriculum. If the public learns that security equals impunity, the next crisis will arrive pre-interpreted against the alliance.

Korea’s Expensive Lesson: Relocation as a Hidden Tax on Deterrence

South Korea offers a different pathway with its price tag. The 2002 Yangju accident, in which two middle-school girls were killed by a U.S. armored vehicle, triggered a wave of protests and a reckoning over the presence north of the Han. Over the following years, the United States and South Korea consolidated and moved the bulk of forces south, culminating in the expansion of Camp Humphreys—now the most significant U.S. overseas base—with South Korea shouldering about 90% of the roughly $10.7–10.8 billion bill. The tripwire logic of having large numbers of Americans near the DMZ yielded to a modern hub-and-spoke posture. Effective, perhaps; inexpensive, no. The fiscal burden was enormous, the political stress long-lasting, and the symbolism unmistakable: when communities lose faith, deterrence adapts by moving—and taxpayers pay.

Relocation mitigates friction but does not erase the underlying legitimacy challenge. Many Koreans saw the southward shift as diluting the “tripwire,” even as analysts argued that deterrence depends more on capabilities and resolve than on geography alone. The core point is transferable: sexual violence and perceived impunity impose a hidden tax on strategy—either in hard costs for concrete and runways or in soft costs for public consent. If allies must repeatedly trade proximity for peace with their citizens, the alliance deterrent may remain credible on paper but thinner in the politics that sustain it. Education systems that build civilian capacity for oversight and early warning are cheaper than do-overs in concrete.

The Education Mandate: Building Institutions That De-Escalate

Treating sexual violence as a strategic risk requires institutions that can prevent it and, when it occurs, contain the legitimacy damage. That is an education mandate in three layers. First, host-nation schools and universities should offer civilian-run “SOFA literacy” modules: plain-language guides to jurisdiction, evidence preservation, and victim services, taught alongside bystander-intervention curricula refined in public health. These are not symbolic; they build shared expectations of process and speed. Second, higher-education clinics should be funded to provide confidential, independent support to survivors outside military command or national police hierarchies—bridging trust gaps while safeguarding evidence. Third, data labs run jointly by universities and prefectural or provincial authorities can track incidents, timelines, and outcomes with dashboards updated in days, not months, calibrated to what communities want to know.

This approach aligns incentives with recent prevention gains reported by the Pentagon without exporting military control into civilian space. DoD’s 2024 report notes a slight decline in reports, the second annual improvement, yet public confidence rests on what people see locally: rapid notification, visible consequences, and services that center on victims. Embedding co-governed education programs in alliance compacts would convert “community outreach” into a standing capability. It should be paid for the way we pay for air defense: as part of deterrence. In Okinawa, that could include 24-hour bilingual campus clinics near base gates and standard 48-hour public briefings triggered by arrests, run by an academic-government board rather than the local base. Prevention works best when it is civil, routine, and boringly reliable.

What the Data Suggest: Estimating the Social-License Cost of Crime

Where complex numbers are scarce, we can still build transparent estimates to guide policy. Consider a simple “social-license cost” model for base hosts. Use three inputs: frequency of severe incidents (sexual assaults and deaths), salience (front-page national coverage days), and process trust (days between arrest and first official bilingual briefing naming the responsible agency and the victim-service pathway). Assign weights based on validated research about scandal persistence in public opinion. For example, a front-page day is a stronger predictor of policy attention than a brief news item, and long silences from authorities prolong outrage. A jurisdiction that suffers two high-salience incidents in a year and takes a week to brief the public faces a dramatically higher “cost score” than a jurisdiction with similar incident frequency but same-day briefings and independent clinics. The model doesn’t invent facts; it imports social science into the alliance dashboard.

Apply the lens retrospectively. In Okinawa, a cluster of severe 2024–2025 cases—combined with public complaints about information-sharing—would produce a high cost score despite any internal DoD progress. In the Philippines, the 1990s base exit followed a long runway of sovereignty-framed grievance; today’s water-cannon incidents re-ignite those frames even as Manila expands EDCA access. In Korea, the 2002 tragedy plus months of protests translated into a multi-billion-dollar relocation that reset friction at the price of distance. None of this says alliances are brittle; it says their social license is measurable and manageable. The education sector, not just defense ministries, should own part of that management through data, clinics, and curricula that shrink the trust deficit when incidents occur.

Policy Design for Tokyo, Seoul, Manila—and Washington

What should policymakers do now? First, institutionalize 24–48 hour joint notifications to local governments after arrests in cases with potential community impact, with a default to public release unless a court-recognized privacy exception applies. Japan’s SOFA practice—U.S. custody until indictment—has long been incendiary; while treaty change is hard, notification speed and data transparency are administrative choices. The metric is simple: do locals feel they learn from authorities before they hear it from social media? That metric should be tracked monthly and published on prefectural dashboards in Japanese and English. Second, dedicate a small, fixed share of host-nation support to civilian-run clinics near bases, contracted through universities. Making care independent of military command and national police can raise reporting while improving evidence quality and survivor trust.

Third, embed “civilian harm mitigation” concepts—now standard in kinetic operations—into alliance compacts for interpersonal harms, with publicly auditable prevention staffing, training hours, and bar/club partnerships in base towns. After a string of alleged assaults in 2024, U.S. forces restricted late-night drinking in Japan; that kind of lever should be tied to data triggers and co-governed with local leaders, not imposed ad hoc after outrage peaks. Fourth, align education ministries and defense ministries on a shared curriculum: bystander intervention, rights and reporting, and cross-cultural campus programs for service members and local youth. The goal is not only fewer crimes but faster trust repair when crimes happen. The price is modest compared to the billions spent on relocation when communities give up on proximity.

Deterrence Begins Where People Live

Return to that opening number: 70.6% of Japan’s exclusive-use U.S. base land packed into Okinawa. Pair it with another: 61% of the 2023 cases involving U.S. personnel recorded there. Add the recent injuries from water cannons in the South China Sea and the memory of two girls killed in Korea in 2002, and we see why sexual violence near bases is not a narrow criminal-justice issue but a strategic one. If left to legal process alone, each shock can metastasize into relocation bills or base-access oscillations that embolden adversaries who thrive on fissures among allies. The alternative is not a press conference. It is a civilian, education-led infrastructure that makes prevention normal and response credible: independent clinics, rapid bilingual briefings, campus-anchored data labs, and SOFA literacy that demystifies procedures before the next crisis hits. Deterrence begins where people live. If we invest in the civil institutions that keep faith after failure, we will preserve the social license that keeps the alliance—and regional balance—intact.

The original article was authored by Hiroshi Fukurai. The English version, titled "Okinawan rights ignored as military crimes persist," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Anadolu Agency. (2024, August 21). 118 criminal cases, including sexual abuse, filed against US soldiers in Japan last year.

Associated Press. (2024, September 6). Japan’s top court orders Okinawa to allow a divisive government plan to build US military runways.

Associated Press. (2025, July). Sex assault reports in the US military fell last year, fueled by a big drop in the Army.

Brooklyn Journal of International Law. (2024). Schmeiser, K. The Japan–U.S. SOFA: Applying a rule-of-law lens.

Defense Department. (2024, May 16). Department of Defense releases FY 2023 Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military.

Defense Department. (2025, May 1). FY 2024 Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military (PDF).

East Asia Forum. (2024, September 6). Okinawans must not be overlooked in new US–Japan counter-crime forum.

East Asia Forum. (2025, August 20). Okinawan rights ignored as military crimes persist.

The Guardian. (2025, April 24). Two US marines investigated over alleged rape at military base in Okinawa.

Hankyoreh. (2024, June 14). 22 years later, Korean girls killed by US troops remain a painful memory.

Mainichi Shimbun (English). (2024, August 21). Over 60% of crimes involving US military personnel in Japan took place in Okinawa.

Military.com. (2024, October 3). Troops in Japan banned from late-night drinking after string of alleged sexual assaults on Okinawa.

Okinawa Prefectural Government, D.C. Office. (n.d.). Base-related data; Governor’s message.

Quincy Institute. (2025, February 12). Defending without provoking: The United States and the Philippines in the South China Sea.

Reuters. (2023, August 22). Philippines completes mission to disputed shoal after Chinese water cannon incident.

Reuters. (2024, March 23; June 17). China coast guard uses water cannons against Philippine vessels; China and the Philippines trade barbs over Second Thomas Shoal.

Reuters. (2018, June 28). U.S. forces chief says South Korea paid for 90 percent of biggest overseas base.

U.S. Army (army.mil / DVIDS). (2016, July 26; 2018, December 17). Rotational soldiers begin 2ID’s historic move to Humphreys; Camp Humphreys becomes major hub.

U.S. Naval Institute, Proceedings. (2024, May). Harding, S. D. There and Back and There Again: U.S. Military Bases in the Philippines.

War on the Rocks / Texas National Security Review. (2021, June 2). Press, D. & Lieber, K. The truth about tripwires: Why small force deployments do not deter aggression.

Comment