From Surplus to Squeeze: Why Germany’s Export Edge Faltered and China’s Rose — and How to Fix the Supply Side

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

The most telling figure in today’s trade debate is not a headline growth rate but an energy and scale wedge. In late 2024, industrial electricity in Germany hovered near €0.20/kWh for mid-sized non-household users, while Chinese gigafactories were ramping through a battery price collapse to roughly $115/kWh at pack level — a 20% fall in just one year — thanks to vast capacity, lower input costs, and ruthless learning curves. That dual wedge — higher European energy/input costs versus China’s rapidly falling tech costs — maps almost one-for-one to the recent decomposition of export market share changes: Germany’s losses are driven by supply-side factors, not a sudden collapse of foreign demand. Put bluntly: the world still buys; Germany is just harder to buy from in energy- and scale-intensive categories, while China has become dramatically cheaper and faster in the same segments. If policy keeps treating this as a demand lull, we will keep missing the lever that matters. The lever is supply — price, productivity, scale, and speed.

Reframing the Debate: From Demand Shortfall to Supply Wedge

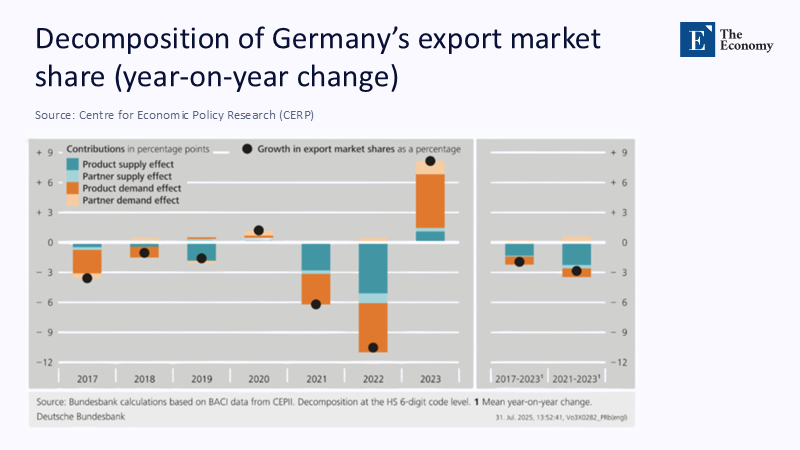

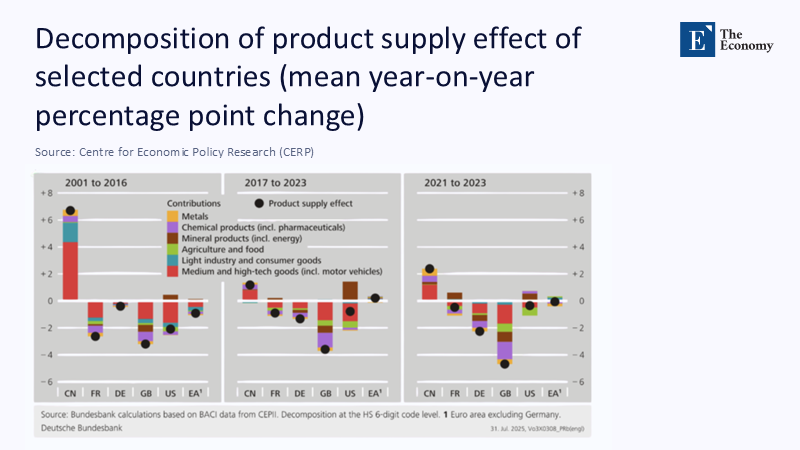

The conventional narrative is that Germany’s export malaise stems from weak global demand and geopolitical uncertainty. That is a partial truth at best. The more revealing frame comes from recent work updating classic market-share decompositions: split changes in a country’s export share into demand-driven effects (shifts in where and what buyers want) and supply-driven effects (price-competitiveness and capability to deliver). The latest VoxEU analysis extends the seminal Gaulier–Cheptea approach and shows Germany’s losses since the energy shock are overwhelmingly supply-side — and, crucially, these can be drilled down into product-level and partner-level effects that flag precisely where costs and capabilities slipped. In other words, it isn’t that the world stopped wanting machines, vehicles, and capital goods; it’s that German producers struggled to deliver them at competitive cost and scale while Chinese rivals could. That reframing matters because it directs policy toward energy, learning, and capacity — not stimulus aimed at buyers.

Germany’s Supply-Side Squeeze: Energy, Labor Costs, and Utilization

Since Russia’s gas cutoff, industrial electricity and gas costs in Germany have stayed above pre-crisis norms despite some easing. Eurostat reports non-household electricity prices fell in the EU in late 2024 but remained elevated by historical standards; German mid-size users were near €0.20/kWh, and even after early-2024 contract relief, SMEs were paying roughly 17.6 ct/kWh before tax — still a competitive drag versus the U.S. and China. Capacity utilization in German industry lingered around the mid-70s to high-70s percent range in early-to-mid-2025, well below long-run averages, reflecting weak order backlogs and rising fixed-cost burdens per unit. Unit labour costs stepped up materially in 2022–2023 and, while wage growth slowed into 2024–2025, higher ULC levels combined with subdued productivity left price competitiveness tight. Put together: expensive energy, soft utilization, and sticky ULC compressed margins just as global competitors could expand. That is a supply squeeze, not a demand drought — and it shows up in the product-level component of the decomposition.

What China Changed: Scale, Cost Curves, and Overcapacity as Strategy

China’s rise is not a mystery of hidden demand; it is a story of scale, speed, and cost curves in strategic manufacturing. In 2023, China produced roughly 29% of global manufacturing output, and in 2024–2025, it powered a historic drop in battery pack prices to about $115/kWh amid cell and materials overcapacity, especially in LFP chemistries. Solar and battery industries ran capacity well beyond near-term demand; the IEA notes Chinese battery output exceeded three-quarters of global supply with utilization below 40% in some segments, while authorities and market players wrestled with how to manage the glut. The export consequence was immediate: China accounted for about 40% of global EV exports in 2024; NEV exports in 1H 2025 cracked one million units, and overall auto exports continued to rise despite growing Western trade defenses. This is the mirror image of Germany’s squeeze: where Germany’s costs rose and capacity idled, China’s costs fell and capacity surged — even at thin margins — shifting the supply-side of market share.

Product- and Partner-Level Supply Effects: Where the Edge Was Lost

The decomposition cited above does more than say “supply matters.” It splits the supply component into product-level effects (can you make the thing at a competitive cost/quality?) and partner-level effects (can you serve the customers where they are with resilient upstream inputs?). Germany’s product-level disadvantage has concentrated in green-tech-adjacent capital goods and autos as battery and power-electronics cost curves tilted toward Chinese incumbents. Partner-level frictions come through energy inputs, grid fees, and supply chains: decarbonization raises transition costs, while elevated grid fees and infrastructure constraints lift delivered prices. Destatis data show German exports stagnated around the 2025 half-year mark, and industrial production in late 2024 was still falling month-on-month; ifo surveys show a rising share of firms reporting lost international competitiveness. These patterns are what you expect when the product-level supply term weakens and partner-level delivery costs rise, even if aggregate demand in destination markets is not collapsing.

The “Second China Shock” — But This Time It Hits Germany’s Core

A decade ago, China’s export surge mainly hammered low-cost U.S. sectors. Today’s shock bites at Germany’s technological core: machinery and autos. Recent analysis shows Germany became a net importer of certain machinery categories from China, while car exports to China slumped as Chinese EVs and intelligent vehicles seized share. At the same time, the EU has moved from provisional to definitive countervailing duties on Chinese BEVs, signaling that Brussels sees subsidized overcapacity as a structural challenge rather than a blip. The Center for European Reform warns that, absent a major policy reset, Germany risks rapid, concentrated industrial job losses as the cost/scale asymmetry persists. Unlike earlier waves, this is not just import competition at the margin; it is a contest over the commanding heights of Europe’s tradable capital-goods base — the sectors that anchor R&D, supplier networks, and regional incomes. Treat it as a cyclical slump and you will treat it too late.

The Supply Ledger, Itemized: What the German Side Can Fix First

When you translate the factor decomposition into a policymaker’s to-do list, the “supply” column reads like a ledger of fixable frictions. First, energy and networks: despite declines from the 2022 peak, industrial electricity remains elevated, network fees have roughly doubled since 2022, and Berlin has resorted to subsidies to mute the pass-through — a patch, not a cure. Second, utilization and order flow: capacity utilization remains several points below long-run norms, raising average costs and discouraging automation investments that would lift productivity. Third, labour cost and productivity: ULC stepped up through 2023; wage moderation and productivity-enhancing capex must meet in the middle. Fourth, permitting and infrastructure: the shift to electrified industry collides with slow approvals and grid build-out; firms struggle to locate and contract sufficient low-carbon power at stable prices. Finally, product transition: German autos and capital-goods makers have been slow to internalize battery, power electronics, and software at Chinese speed and cost, leaving value capture outside their traditional core. Each friction bleeds into the product- and partner-level supply terms; each is within policy reach.

Evidence Beyond Decomposition: The Macroeconomic Backdrop

The macro picture corroborates the micro mechanics. Germany’s economy contracted again in 2024 and limped into 2025 with muted investment, still-elevated energy costs, and strained industrial order books. Eurostat shows labour cost pressures moderating but still rising; ifo’s business climate improved only slightly by mid-2025 and capacity utilization stayed below average. Meanwhile, Destatis recorded mixed trade and production data in late 2024, with month-on-month falls in industrial output. None of this implies that buyers disappeared. Rather, it shows producers battling a cost base and transition timeline that turned unfavorable. The fact that EV trade volumes grew globally in 2024, with China’s exports expanding again in 1H 2025, highlights the asymmetry: demand in key tradables is there; supply-side competitiveness determines whose factories run at 90% and whose idle at 77%.

Policy Translation: A Supply-First Playbook That Matches the Math

If the issue is supply, the appropriate solution isn't a broad stimulus but rather targeted cost-curve adjustments. Begin by addressing energy agreements and networks: enhance firm-level access to long-term power purchase contracts, boost renewable energy sources in industrial clusters with expedited grid connections, and substitute universal fee subsidies with focused assistance based on verifiable investments that enhance productivity. Next, encourage learning: China’s advantage in batteries and power electronics stems from a hands-on approach to learning. Europe can shorten the learning process by conditioning market entry on partnerships that mandate technology transfer and domestic upstream content, supported by stringent milestones rather than just high-level promises. Berlin should also recalibrate capital allowances to prioritize software, automation, and electrification tools with immediate deduction options and quicker approval processes to stimulate productivity. Lastly, ensure that trade defenses are consistently applied over time: maintain countervailing duties long enough for productivity improvements to take hold, while linking them to transparent benchmarks so that the industry understands it must bridge the gap rather than rely on indefinite measures. These actions aren't against market principles; they serve to rectify a skewed competitive landscape where excess capacity has become an alternative form of industrial policy.

Anticipating the Critiques — and Meeting Them with Evidence

Critique one says this is demand, not supply: that buyers simply wanted fewer German goods. But EV trade, Chinese auto exports, and ongoing global capital-goods flows contradict that claim; Germany’s own surveys and utilization data point to cost-side stress, not evaporated orders. Critique two says energy prices have fallen, so the problem must lie elsewhere. True, prices eased from the 2022 spike, but they remain structurally high versus the U.S. and volatile for power-intensive production; grid fees and infrastructure constraints magnify the wedge. Critique three objects that trade defenses will backfire. Yet the EU’s BEV duties are targeted at documented subsidy-driven overcapacity; they are a bridge to rebuild competitiveness, not a permanent moat, and should be paired with the joint-venture learning strategy to avoid sheltering inefficiency. The final critique asserts that labour costs are immovable. They are not: ULC is the ratio of wages to productivity; the denominator is policy-sensitive through capex, automation, and permitting. Evidence across these points consistently returns to the same conclusion: fix supply first.

Closing the Loop: Back to the Wedge

Return to the opening wedge: high-and-sticky European industrial energy costs and China’s precipitous tech cost declines. That wedge is the visual metaphor for the factor-analysis finding that supply, more than demand, explains the shift in export competitiveness. Germany can narrow it. Lock in cheaper, cleaner electrons for factories; accelerate approvals to lift utilization; push productivity-enhancing capex across software, automation, and electrified process heat; insist on joint-venture learning in green-tech value chains while preserving targeted trade defenses long enough to matter. The alternative is to pretend that everyone’s buying less of what Germany sells — when the truth is the world is buying plenty, but at prices and from plants that Germany no longer matches. The market is not waiting. It is reallocating. And unless policy meets the decomposition with a supply-first plan, the next set of export-share charts will tell the same stark story, only louder.

The original article was authored by Philipp Meinen and Arne Nagengast. The English version of the article, titled "Why some countries win in world trade: Unpacking export competitiveness," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Agora Energiewende. (2025, Jan. 10). The energy transition in Germany: state of play 2024 (slides).

Associated Press. (2025, Jan.). Germany’s economy is in the dumps. Here are 5 reasons why.

BloombergNEF. (2024, Dec. 10). Lithium-ion battery pack prices see largest drop since 2017, falling to $115/kWh.

Business Insider. (2025, Aug.). Inside BYD’s plan to rule the waves.

Center for European Reform. (2025, Jan. 16). How German industry can survive the second China shock (policy brief).

CEPR VoxEU. (2025, Aug. 20). Meinen, P., & Nagengast, A. Why some countries win in world trade: Unpacking export competitiveness.

CEPR VoxEU. (2025, Aug. 7). Marin, D. The China shock hits Germany.

Clean Energy Wire (BDEW). (2024, Feb. 20). Industry electricity prices for German companies drop almost one quarter in early 2024.

Destatis (German Federal Statistical Office). (2025, Feb. 7). Production in December 2024: –2.4% on the previous month.

Destatis (German Federal Statistical Office). (2025). Foreign trade — Key figures.

European Commission. (2024, July 3). Provisional duties on battery electric vehicles from China.

European Commission / Eurostat. (2025, May 6). Household electricity prices in the EU stable in 2024; and Electricity price statistics (non-household).

Financial Times. (2025, Aug.). European industry grapples with shift to green power for factories.

Financial Times. (2025, Jan.). German economy shrinks for second consecutive year.

FRED / OECD. (2025). Unit labour costs: Germany (series ULQEUL01…).

IEA. (2024–2025). Global EV Outlook 2024–2025 (battery and trade insights).

OECD. (2024, Dec.). Economic Outlook 2024/2: Germany chapter.

Statista. (2025, Apr. 16). China is the world’s manufacturing superpower (share of global output, 2023).

Trade.gov (U.S. Department of Commerce). (2025, Aug.). Germany — Energy: industrial power prices comparison.

VoxEU / ECB & CEPR contributors. (2025, Feb.). The recent weakness in the German manufacturing sector.

Comment