Surpassing Chips: The Quad’s Inevitable Rare-Earth Independence—and How to Accelerate the Timeline

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

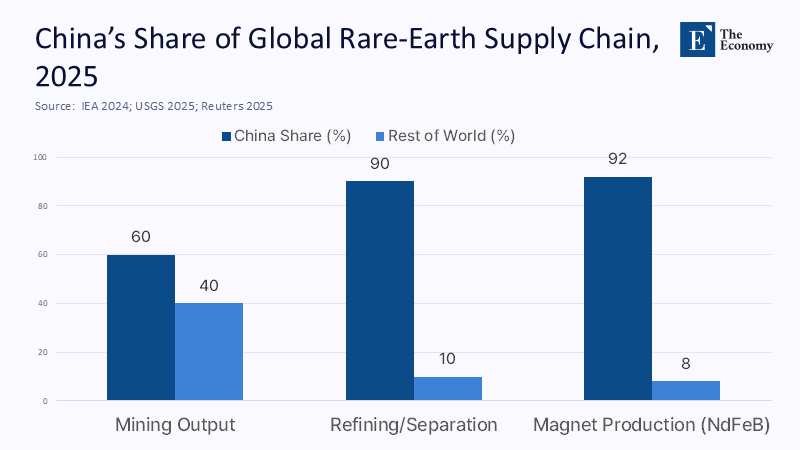

When China tightened export licensing on certain rare earths and magnets this spring, European auto suppliers briefly stopped production. U.S. buyers faced weeks-long delays for approvals. This highlighted Beijing’s control over roughly 90 percent of global rare-earth refining and more than 90 percent of permanent-magnet output. In the same month, Washington set a price floor of $110 per kilogram for neodymium-praseodymium (a rare-earth metal used in the production of powerful magnets) and invested in MP Materials. Meanwhile, Australia moved toward A$1.2 billion in public support for the Nolans NdPr project. Japan’s JOGMEC secured heavy rare-earth supplies from France’s Caremag, and India’s IREL announced magnet partnerships with Japanese and Korean companies. These actions are not mere gestures. Unlike advanced chips—where mastering extreme-ultraviolet lithography takes a long time—the processes behind rare-earth mining, separation, metal-making, and magnets are demanding but well-established. The Quad's central question is no longer whether it can break China’s grip; it is how quickly it can achieve that before the next supply shock occurs.

From Leverage to Liability: Recasting the Problem as a Timetable

The prevailing narrative says Chinese dominance in rare earths is so entrenched that alternatives cannot scale in time. That fatalism misreads the technology curve. Chips demand frontier equipment, proprietary design stacks, and networks of tacit know-how. Rare-earths demand patient capital, environmental compliance, trained operators, and an industrial ecosystem whose core processes—cracking, solvent extraction, calcination, strip-casting—have been understood for decades. China’s advantage is not mystery science; it is decades of policy-enabled scale and a permissive regulatory envelope. That is precisely why recent policy shifts matter: when the U.S. Defense Department backstops prices and offtake, when the EU sets 27-month permit clocks for extraction and 15-month clocks for processing and recycling, and when Australia and Japan mobilize state development banks, the binding constraint shifts from scientific feasibility to administrative tempo and capital cyclicality. Treat the problem as a timetable, not a technological moonshot, and the path out of dependence becomes visible.

Strategic Shift: From Chinese Dominance to Global Diversification

The second reframing is strategic. Chinese export controls are intended to signal power and extract concessions. But controls also push customers to diversify, catalyzing investment and institutional learning that erode the very leverage Beijing seeks to preserve. The 2010 episode with Japan’s rare-earth supply ended in accelerated diversification; today’s wider curbs are triggering a larger response: the Quad has formalized critical-minerals cooperation; the U.S. is standing up a magnet pricing benchmark; and allied governments are underwriting refineries and magnet plants precisely because the security externalities dwarf any temporary cost premium. In this light, China’s chokehold is a wasting asset. The more it is exercised, the faster its half-life decays. This strategic shift from Chinese dominance to global diversification is a reassuring sign for the future.

What the Numbers Say: Dominance vs. Replaceability

Start with scale. The International Energy Agency estimates China accounts for roughly 60 percent of rare-earth mine output and over 90 percent of refining; journalism and industry trackers place magnet production at ~90–94 percent. On the demand side, EVs and wind will keep magnet rare-earth demand growing this decade, even as substitution and efficiency nibble at the margins. Meanwhile, the U.S. Geological Survey shows non-Chinese mine output expanding from Australia, the United States, and Myanmar, with multiple separation projects moving to sanction. The core insight: dominance is high, but the technical replaceability of each stage is real—and already in progress.

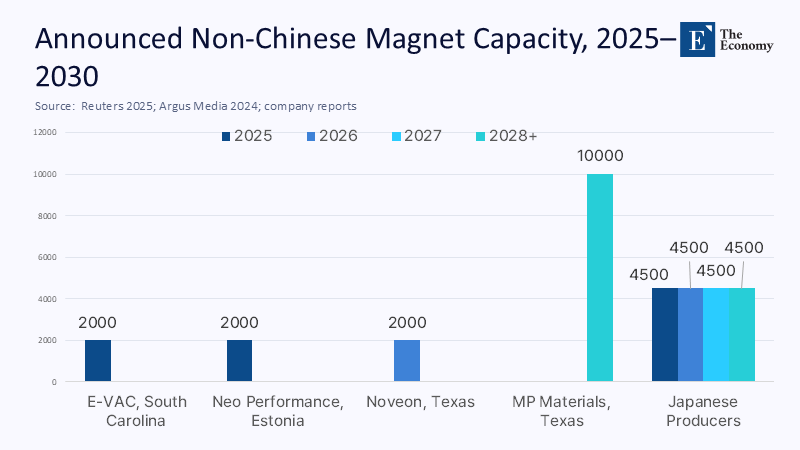

Non-Chinese Magnet Production: A Potential Game Changer. Now consider magnets, the narrowest choke point. Publicly announced non-Chinese capacity through 2028 is no longer trivial. Reuters reports MP Materials plans 10,000 t/y of NdFeB magnets in Texas by 2028 under a Pentagon-backed program; VAC’s E-VAC facility in South Carolina targets initial production in 2025; Neo Performance Materials is commissioning ~2,000 t/y in Estonia; Noveon in Texas guides to ~2,000 t/y with offtakes into motors; and Japanese producers already deliver ~4,500 t/y domestically. Taken together, these projects plausibly push allied magnet output into the 20,000-ton range before the decade ends, with high confidence of further scale. This non-Chinese magnet production has the potential to be a game-changer, bringing optimism for the future.

Why Speed, Not Feasibility, Is the Binding Constraint

While the chemistry is established and projects are emerging, achieving liberation isn’t instantaneous due to stubborn lead times. These delays stem from permitting, community consent, grid and water connections, tailings design, skilled labor, and the S-shaped ramp curves of projects. In the U.S., mine permitting often takes 7–10 years, with environmental assessments averaging 4–5 years. The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act aims to shorten these timelines, but mainly strategic projects will see benefits, necessitating well-resourced regulators. This explains the efficiency gap compared to Beijing, highlighting the need to eliminate bottlenecks without sacrificing environmental standards. The importance of speed in overcoming these feasibility constraints cannot be overstated, underlining the urgency of the situation.

The urgency around security is speeding this process. In July 2025, the Quad foreign ministers identified minerals as vital for resilience, leading to increased financial risk-sharing among allied nations. Australia is mobilizing debt and equity to advance projects like Arafura’s Nolans. The U.S. is using Defense Production Act funds and a price floor to address the classic investment paradox where low prices hinder supply. The strategy aims to mitigate public risk initially, tapering as scale and efficiency improve.

The Fastest Path to Autonomy: A Quad Production Playbook

A credible independence plan should focus on securing magnets first, followed by access to heavy rare earths and diversified separation capacity. By aggregating production from various sources like MP’s Texas lines and expansions in Japan and Europe, a secure magnet supply can be established within 36–48 months, provided that offtakes and OEM qualifications are in place. The government can help by standardizing magnet specifications, offering multiyear purchase guarantees, and incentivizing motor manufacturers to co-locate with magnet plants, aiming for a reliable capacity that protects allies from supply disruptions.

For upstream materials, the light-rare-earth pathway is more straightforward with projects like Arafura’s NdPr-oxide plan and Lynas’ production chain. However, the heavy rare earths, such as dysprosium and terbium, are more challenging due to their concentration in China and Southeast Asia. Japan's partnerships for heavy rare earths, along with targeted funding for separation technologies in the U.S. and EU, are essential. Until new mines can meet demand, recycling and designs that reduce reliance on heavy rare earths will help close the supply gap.

Data, Estimates, and a Transparent Method

The Quad could reduce its reliance on Chinese magnets by 2028-2030 with a potential non-Chinese magnet capacity of about 17,000–18,000 tons per year (t/y). This includes contributions from several sources: MP Texas (10,000 t/y), E-VAC South Carolina (at least 2,000 t/y), Neo Estonia (around 2,000 t/y), Noveon Texas (around 2,000 t/y), and Japanese firms (4,500 t/y). I have reduced these numbers by 20% to account for possible delays.

We can also expect some growth from modest projects in the EU and early recycling contributions from HyProMag, which could add 100 to 500 t/y.

These estimates rely on announced capacities adjusted for risks, exclude projects that are not yet funded, and assume that global magnet demand will grow at a stable rate until 2027. If these assumptions change, the timeline for independence may shift. Still, the overall trend remains the same: the Quad’s capacity is expected to increase, reducing dependence on China and lowering the risk of a magnet shortage.

Anticipating the Pushback—and Answering It

Critique one argues that allied output will be insignificant because China can undercut prices. This misunderstands the difference between price control and supply stability. The Pentagon’s price floor and long-term contracts aim to mitigate predatory pricing, making China’s temporary price drops operate as a subsidy for allied production. As these contracts extend to civil buyers, they signal to investors that the price floor is solid, creating a credible counterweight against market manipulation.

Critique two suggests that permitting and ESG concerns will hinder new projects. However, Europe’s CRMA and Australia’s blended finance address these issues without compromising safeguards. In the U.S., improved inter-agency coordination can reduce environmental review times while ensuring community consent. According to OECD and U.S. data, mining bottlenecks are often related to workforce management rather than regulatory timelines, which can be addressed through better training and centralized permitting. This approach may be slower than Beijing’s model, but it is sustainable and resistant to legal challenges.

Critique three raises the issue of substitution, asking if magnet-free motors render all this unnecessary. While it’s wise to explore alternatives, magnet-based drivetrains will still make up around 94% of traction motors by 2025. For grid stability and defense applications, NdFeB remains the standard. The key takeaway is to invest in substitutes where feasible but consider them as complements, not replacements, for at least the next decade.

What the Quad Should Do Next—So the Clock Runs Faster

Two accelerators deserve emphasis. First, synchronize standards across the Quad for magnet grades, defense qualification, and ESG reporting. Today, firms must navigate four versions of compliance; one harmonized template would compress qualification cycles by quarters, not weeks. Second, over-invest in heavy-rare-earth pathways now: finance ion-adsorption-clay projects in friendly jurisdictions; co-fund heavy-oxide separation modules in allied refineries; and expand grants for Dy/Tb-saving grain-boundary diffusion in magnets, which can cut heavy additions materially. Japan’s JOGMEC move into Caremag is the right instinct—multiply it. A security-grade stockpile of heavy oxides, refreshed via recycling, would ensure the gap until new mines flow.

The industrial policy edge is already visible. The A$7 billion NAIF and Australia’s Critical Minerals Facility are underwriting logistics in the Pilbara and Northern Territory; the U.S. has shown a willingness to become a direct equity participant; and Europe’s permit clocks are finally ticking. Tie these together through the Quad’s Investors Network. Publish a shared pipeline of investable projects with transparent status, risks, and policy tools attached. Then hold quarterly “bankability reviews” that de-risk the next tranche of projects—not with press releases, but with signed credit agreements and interlocking offtakes that move material through real plants.

Tie-back and Call to Action

Ten years ago, a single political conflict could have halted Japan’s supply of rare earth elements. This spring, China's tightening of licenses caused a ripple effect in Europe and prompted another set of contingency strategies. These incidents have a common theme: dominance without certainty. Rare-earth elements differ from chips. They present challenges related to capital and coordination that are masked as chemistry. The Quad has already altered the incentives with established price floors, public investments, permit timelines, and a focus on national security. If these levers are pushed further and faster, the landscape could change significantly in five years: allied magnet production will address both defense and essential civilian requirements; NdPr oxide supply will flow from Australia and the U.S. through allied refineries to allied manufacturing plants; strategic sourcing, diffusion technologies, and large-scale recycling will lessen the risk associated with heavy rare earths. The impact on Beijing’s influence is clear: the more pressure it applies, the less significant it becomes. The current task is to execute swiftly—align standards, approve necessary actions, finance heavy separation processes, and establish recycling infrastructures. Turn independence from a mere slogan into a historical benchmark. Then continue until the next disruption barely causes a ripple.

The original article was authored by Manish Vaid, a Junior Fellow with the Observer Research Foundation. The English version, titled "China’s critical minerals chokehold sparks Quad action," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Arafura Rare Earths. “Investor Presentation & Project Overview: Nolans NdPr Oxide (4,440 t/y).” ASX Announcement, Dec. 13, 2023 / updated materials 2024–2025.

Argus Media. “E-VAC secures $335mn for US permanent magnet plant.” Sept. 5, 2024.

European Commission. “Critical Raw Materials Act.” Official portal (permit clocks of 27 months for extraction, 15 months for processing/recycling). 2024–2025.

Financial Times. “China cracks down on foreign companies stockpiling rare earths.” Aug. 2025.

Fastmarkets. “Rare-earth magnet production outside Asia gearing up (Neo Estonia; MP Materials Texas first-phase).” Jan. 10, 2024.

HyProMag / Fastmarkets. “Recycling capacity ramp (UK/Germany/U.S.).” Apr. 4, 2024.

IEA. Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024/2025 (magnet rare-earth demand outlook; China’s share of refining). 2024–2025.

JOGMEC. “Equity and Debt Financing to Caremag SAS—heavy rare-earth supply for Japan.” Mar. 17, 2025; Argus confirmation.

Noveon Magnetics. Company materials on U.S. NdFeB capacity (~2,000 t/y) and offtakes. 2023–2025.

OECD LEED. “Mining for Talent: Addressing regional workforce challenges in a changing resources industry.” June 2025.

Reuters. “MP Materials partners with DoD; 10,000 t/y U.S. magnet output by 2028; $110/kg price floor.” July 10, 2025.

Reuters. “China rare-earth export curbs and monthly export trends, 2025.” June 9, 2025.

SME / U.S. permitting brief. “It takes 7–10 years to secure a mine permit in the U.S.” Accessed 2024–2025.

U.S. Department of Defense. “AUSMIN joint statement (critical minerals); Lynas U.S. heavy REE awards (Hondo, TX); DPA actions.” 2021–2025.

U.S. Department of State. “Quad Foreign Ministers’ Statement—critical minerals resilience.” July 1, 2025.

U.S. Geological Survey. Mineral Commodity Summaries 2025—Rare Earths (world production; U.S. statistics). Jan. 31, 2025.

VAC (Vacuumschmelze) / Argus Media. “E-VAC South Carolina plant timeline.” 2024–2025.

World/Industry Coverage on Motor Substitution. S&P Global Mobility. “Rare earth elements: Auto industry looks beyond China (94% magnet-based traction motors in 2025).” July 28, 2025.

Comment