Conditional Brotherhood: Why Beijing Will Buy Iran's Oil—But Will not Bleed for It

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

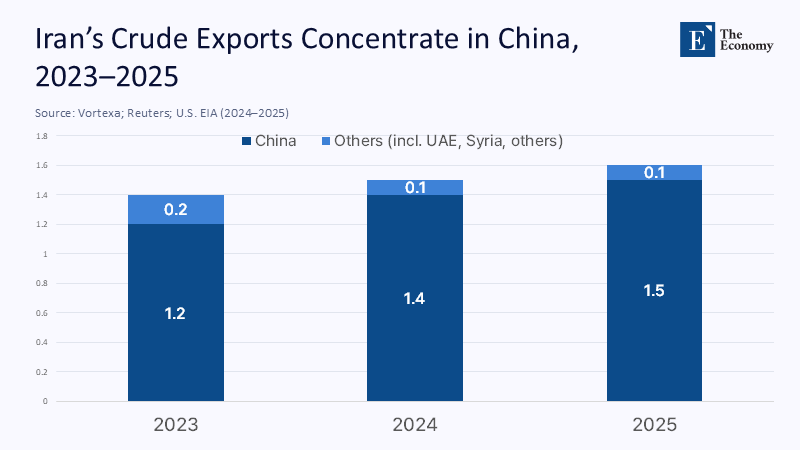

In 2023, 90% of Iran's crude oil exports were sent to China, a significant increase from just a quarter before the reimposition of U.S. sanctions in 2018. This remarkable dependency suggests a straightforward narrative of a tightening alliance that could transform rhetoric into military action. However, China's conduct during this year's confrontation between Israel and Iran presented a different perspective. Beijing made pointed statements, engaged in diplomacy at the United Nations, and avoided any actions that might draw it into direct conflict. The statistics clarify the situation. As the largest crude importer globally, China values price stability, reliable shipping routes, and flexibility in geopolitical matters more than ideological alignment. Although it currently takes in the bulk of Iran's oil, this exchange serves as a commercially advantageous hedge rather than an obligation of military support. When conflicts arose, Beijing's backing was intentionally restrained. This is the pragmatic reality that regional players must consider. While China will continue purchasing, it will do so until the costs outweigh the advantages, but it will not engage in Iran's conflicts.

Reframing the Question: From "Axis" to Risk Management

China's posture toward Tehran is best understood as risk management, not alliance politics. In the war scare, Beijing condemned Israeli strikes and called for restraint, but it avoided moves that would have raised the odds of confrontation or secondary sanctions. Analysts across think tanks and newsrooms converged on the same assessment: China's leverage in the crisis was limited, and its incentives ran through energy security and global market stability, not revolutionary solidarity. These reframing matters because it shifts attention from speeches to supply chains—from rhetorical alignment to the concrete mechanics of oil, shipping, insurance, and payments. It implies that future "backing" will be calibrated, transactional, and reversible, rather than an ironclad strategic guarantee.

The limits were visible at the United Nations and beyond. Chinese diplomats blasted Israeli operations against Iran's territory, urged de-escalation, and telegraphed the familiar language of sovereignty and non-interference. But there was no sign Beijing would risk military entanglement or even expend serious political capital to coerce Israel, Washington, or Gulf partners. That asymmetry—loud censure paired with light leverage—maps onto China's broader Middle East approach since brokering the Iran–Saudi thaw in 2023: encourage calm, harvest economic upside, and avoid taking ownership of other states' wars. The lesson for Tehran's leadership is clear: moral sympathy is cheap; strategic cover is expensive—and China is not purchasing the latter.

What Beijing Would—and Would Not—Risk

Why wouldn't China "show up" for Iran beyond statements? Because the war calculus looks unforgiving in Beijing. A wider fight risks disruption through the Strait of Hormuz, where LNG and crude flows that matter for China's economy would be exposed; it would also collide with priorities closer to home, including deterrence dynamics around Taiwan and the South/East China Seas. China's strategy during the 12-day Israel–Iran war was to buy time, cushion energy shocks, and preserve maneuvering room—consistent with assessments from U.S. and European policy institutes that Beijing is unwilling and unable primarily to impose outcomes in a fast-moving conflict it does not control.

The energy math reinforced caution. Even a brief conflict pushed crude up by $10 per barrel, squeezing China's independent refiners that rely on sanctioned barrels to pad thin margins. Escalation would have amplified the shock, forced costlier rerouting and insurance, and invited fresh U.S. sanctions on coordination nodes inside China. In that world, the pragmatic response is not to take Iran's side militarily but to diversify away from chokepoint risk—for example, by reconsidering land-based gas pipelines from Russia and pacing purchases to rebuild storage. Chinese behavior matched that script.

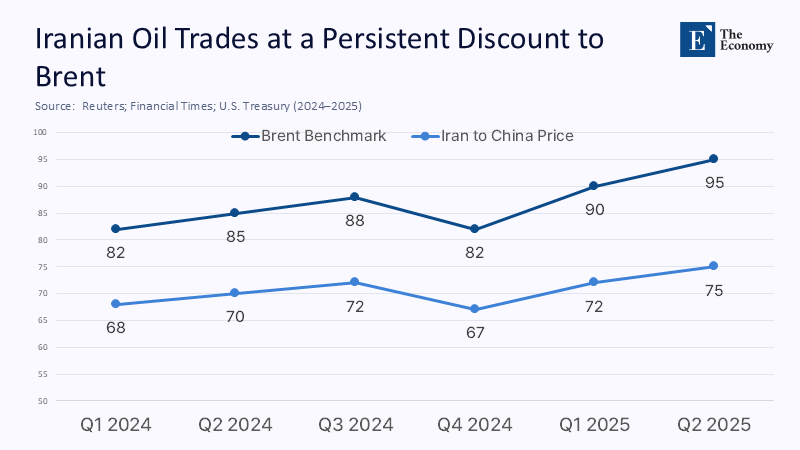

The Oil Tie That Binds—At a Discount

At first glance, the oil relationship between China and Iran appears to be a lifeline. In 2025, Iran supplied approximately 13–14% of China's crude purchases, with flows surging to 1.5–1.8 million barrels per day by mid-year, primarily directed to 'teapot' refineries in Shandong. These volumes traverse a gray ecosystem— 'Malaysian' blends, ship-to-ship transfers, and dark-fleet tankers—that ensures the continuous flow of cargoes while shielding Chinese majors from sanctions exposure. The price signal is clear: Iranian barrels are priced at a discount to ICE Brent, often deeper when global benchmarks spike. In essence, Beijing's 'backing' is expressed through bids, not battalions.

However, this channel is not without its vulnerabilities. The U.S. has targeted traders, tankers, and even a China-based storage terminal linked to these flows, and the Treasury has identified specific Shandong buyers by name. The sanctions framework is adaptable: if the U.S. escalates to financial plumbing—banks, yuan clearing, marine insurers—the cost of handling Iranian crude could skyrocket, reducing arrivals regardless of Beijing's rhetoric. The very characteristics that make the trade feasible—opacity, intermediaries, thinly capitalized players—also make it susceptible to regulatory pressure. Buying at a discount does not equate to underwriting Iran's resilience.

Tehran's Trade-Offs: Revenue Today, Leverage Tomorrow

For Iran, the China channel is both a lifeline and a constraint. Tanker tracking data suggests that exports rebounded to 1.4–1.5 mb/d between 2023 and 2025, but with a high concentration of destinations. Selling to a single dominant buyer in the shadow of sanctions undermines bargaining power, resulting in deeper discounts, delayed payments, and reliance on intermediaries with their own risk thresholds. Analysts point out that structural constraints—aging fields, rising domestic consumption, under-investment—limit how much Tehran can ship even if sanctions are eased. The paradox is that the more Iran depends on China, the less leverage it has over the price China is willing to pay.

This helps explain Iran's behavior during and after the fighting. Lacking allied military cover and facing the prospect of revenue disruptions if tankers are interdicted or insured routes dry up, Tehran accepted the ceasefire parameters without securing binding commitments from major powers. Its leadership may have imagined a brotherhood of the sanctioned; it got transactional solidarity instead. The political consequences will unfold over years, but the near-term economic ones are already visible: more oil moving at steeper discounts to the one buyer willing to navigate the gray channels.

The Education and Administrative Angle: What Institutions Should Plan For

Education systems are not spectators to energy geopolitics. When Brent spends $10 in a week, utility and transport line items on university budgets feel it months later. Chinese and Iranian institutions—already managing currency constraints and compliance risk—will find international partnerships harder to finance if shipping insurance tightens or if secondary sanctions spook banks. Campuses with Middle East programs must prepare travel advisories that shift by the news cycle and recalibrate risk assessments for fieldwork, visiting scholars, and student exchanges. The operational takeaway is mundane but essential: budget stress-testing for energy shocks and rigorous sanctions compliance workshops are no longer optional.

Curricula should adapt as well. The year's events turned sanctions compliance, commodity coordination, and maritime law into everyday policy questions. Schools of public policy and international business can seize this moment by building cross-training modules: students who can read a tanker-tracking dashboard, parse a UN draft resolution, and model a refinery margin are far more employable than those trained in a single silo. For institutions in China and the Gulf, joint seminars on energy security and financial plumbing would pay immediate dividends; for European programs, case studies on secondary sanctions and export controls are already in demand among public agencies and regulated industries.

What Comes Next: Conditional Support, Quiet Diversification

Will Beijing keep buying Iranian oil under sanctions? Yes—if two conditions hold: discounts remain attractive, and sanctions stay calibrated to coordination rather than to core financial channels. China has publicly resisted U.S. demands to cut purchases from Iran and Russia. If yuan-denominated trade and non-Western insurers suffice, the economics will remain compelling for "teapots" that need cheap feedstock. Yet policy hedging is underway: reconsideration of land-based gas pipelines and continued stock building suggest a portfolio mindset rather than lock-in to any one supplier or route. That is not brotherhood; it is a procurement strategy.

For Tehran, the medium-term risk is that margins compress further as global benchmarks fluctuate and as China bargains harder in a buyers' market padded by Russian, Venezuelan, and West African barrels. Meanwhile, enforcement innovations—from blocklists of hulls and hubs to pressure on Chinese storage and blending sites—could periodically jam the channel. The more Iran's exports concentrate, the more any regulatory tweak in a Chinese port or a bank compliance office can function like a lever on its fiscal capacity. No speech in the UN chamber can fix that structural vulnerability.

The Price of Not Starting World War III

The opening statistic of this column—90% oIran’s oil being shipped to China—might appear to signify a bond of political loyalty. However, it’s merely a reflection of a market adaptation shaped by sanctions, resulting from China's discount-driven demand and cautious stance. When faced with a crisis, China's leadership determined that supporting Tehran militarily could lead to energy instability and potentially alarming situations near Taiwan; they opted for a strategy of de-escalation and discounted oil imports instead of confrontation. This decision did not betray Iran but instead uncovered the true nature of their relationship: purchases that rely on conditions, limited diplomatic backing, and ongoing diversification efforts. For those in education and policy-making, the imperative is clear. Develop analytical skills that connect the mechanisms of sanctions to budgetary and security implications; prepare institutions to withstand fluctuations in energy supply; and educate future generations on how to navigate a landscape where information circulates rapidly, yet oil is transported by tanker. The forthcoming crisis will again challenge the distinctions between friends, buyers, and those who fulfill both roles—plan for the buyer.

The original article was authored by Jesse Marks, the CEO and Managing Director of Rihla Research & Advisory LLC. The English version, titled "Iran’s bid for Beijing’s backing meets its limits," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

ABC News (Australia). (2025, June 24). As ceasefire looms, China’s UN peace talk highlights limits of influence.

Associated Press. (2025, June 24). Beijing, a longtime friend of Tehran, turns to cautious diplomacy in Iran’s war with Israel.

Chatham House. (2025, June 30). The Israel–Iran ceasefire is a relief for China. But the war exposed Beijing’s lack of leverage.

Financial Times. (2025, August 20). The Iranian connection: how China is importing oil from Russia (and others) via dark fleets.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2024, October 10). Country Analysis Brief: Iran.

U.S. Institute of Peace. (2025, June 23). What’s at stake for China in the Iran war?

U.S. Treasury. (2025, April 16). Treasury increases pressure on Chinese importers of Iranian oil.

Reuters. (2025, June 14). China’s UN envoy condemns Israeli strikes on Iran.

Reuters. (2025, June 20). Discounts deepen on Iranian oil in China.

Reuters. (2025, June 24). China’s heavy reliance on Iranian oil imports—about 13.6%.

Reuters. (2025, June 27). China’s Iran oil imports surge in June on rising shipments.

Reuters. (2025, August 18). China still storing crude even as refinery runs rise.

The Wall Street Journal. (2025, June). If Iran’s oil is cut off, China will pay the price.

The Wall Street Journal. (2025, June). Israel–Iran conflict spurs China to reconsider Russian gas pipeline.

U.S. Treasury / Reuters. (2025, April 10). U.S. targets China oil storage terminal in new Iran-related sanctions.

Vortexa. (2025, August 5). Iran’s July oil exports hold at 1.5 mb/d despite sanctions.

Comment